Published online Oct 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4986

Peer-review started: July 27, 2020

First decision: August 7, 2020

Revised: August 14, 2020

Accepted: September 9, 2020

Article in press: September 9, 2020

Published online: October 26, 2020

Processing time: 91 Days and 3.8 Hours

Anastomosing hemangioma (AH) is a rare subtype of benign hemangioma that is most commonly found in the genitourinary tract. Due to the lack of specific clinical and radiologic manifestations, it is easily misdiagnosed preoperatively. Here, we report a case of AH arising from the left renal vein that was discovered incidentally and confirmed pathologically, and then describe its imaging characteristics from a radiologic point of view and review its clinicopathologic features and treatment.

A 74-year-old woman was admitted to our department for a left retroperitoneal neoplasm measuring 2.6 cm × 2.0 cm. Her laboratory data showed no significant abnormalities. A non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed a heterogeneous density in the neoplasm. Non-contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a heterogeneous hypointensity on T1-weighed images and a heterogeneous hyperintensity on T2-weighed images. On contrast-enhanced CT and MRI scans, the neoplasm presented marked septal enhancement in the arterial phase and persistent enhancement in the portal phase, and its boundary with the left renal vein was ill-defined. Based on these clinical and radiological manifestations, the neoplasm was initially considered to be a neurogenic neoplasm in the left retroperitoneum. Finally, the neoplasm was completely resected and pathologically diagnosed as AH.

AH is an uncommon benign hemangioma. Preoperative misdiagnoses are common not only because of a lack of specific clinical and radiologic manifestations but also because clinicians lack vigilance and diagnostic experience in identifying AH. AH is not exclusive to the urogenital parenchyma. We report the first case of this neoplasm in the left renal vein. Recognition of this entity in the left renal vein can be helpful in its diagnosis and distinction from other neoplasms.

Core Tip: Anastomosing hemangioma (AH) is difficult to recognize because of its rarity and atypia. Herein, we report a case of AH in an old woman that was discovered incidentally and confirmed pathologically. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of AH reported in the left renal vein. Recognizing that AH may occur in the left renal vein will help improve doctors' vigilance and reduce the probability of misdiagnosis.

- Citation: Zheng LP, Shen WA, Wang CH, Hu CD, Chen XJ, Shen YY, Wang J. Anastomosing hemangioma arising from the left renal vein: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(20): 4986-4992

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i20/4986.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4986

Hemangiomas are most common in the skin or subcutaneous soft tissue, while few occur in the liver, kidney, and other parenchymal organs. Morphologically, most are classic capillary hemangiomas or venous hemangiomas. In 2009, Montgomery and Epstein[1] reported a unique type of capillary hemangioma occurring in the kidney and testis. Its morphology consists of an ethmoid, sinusoid, anastomosing vascular pattern lined with hobnailed endothelial cells, which is similar to the red pulp of the spleen, and the mass was first named “anastomosing hemangioma” (AH). Subsequently, a few cases of AH were reported in the liver, gastrointestinal tract, retroperitoneum, ovary, bladder, adrenal gland, nasal cavity, and intracranial space[2-9].

Here we report the case of a 74-year-old woman who presented without any symptoms and was accidentally found to have a left retroperitoneal neoplasm by imaging examination. After surgical resection, the neoplasm was pathologically diagnosed as AH.

A 74-year-old woman was admitted to our department for a left retroperitoneal neoplasm that was found 1 mo prior during a routine checkup.

One month prior, abdominal non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) at a local hospital revealed a left retroperitoneal neoplasm. However, the patient had no symptoms.

The patient had a history of hypertension for 20 years and had been taking 0.15 g irbesartan once a day to control blood pressure to within the normal range. In addition, the patient had a history of auricular fibrillation for 1 mo and had been taking 0.1 g aspirin each night for anticoagulant therapy and 47.5 milligrams succinic metoprolol once a day to control the heart rate to approximately 90 beats/min.

The patient had no superficial lymph node enlargement. An abdominal physical examination showed that her abdomen was flat and soft without tenderness.

Routine blood tests, biochemical function, coagulation function, and tumor markers, as well as the levels of cortisol (19.13 μg/dL, reference range 6.24-18 μg/dL), aldosterone (105.04 ng/L, reference range 50-313 ng/L), the three hypertension items [plasma renin activity, 1.03 μg/L/h, reference range 1.45-5 μg/L/h; angiotensin I, 0.96 μg/L; angiotensin II, 50.19 ng/L, reference range 32-90 ng/L) were all within normal ranges.

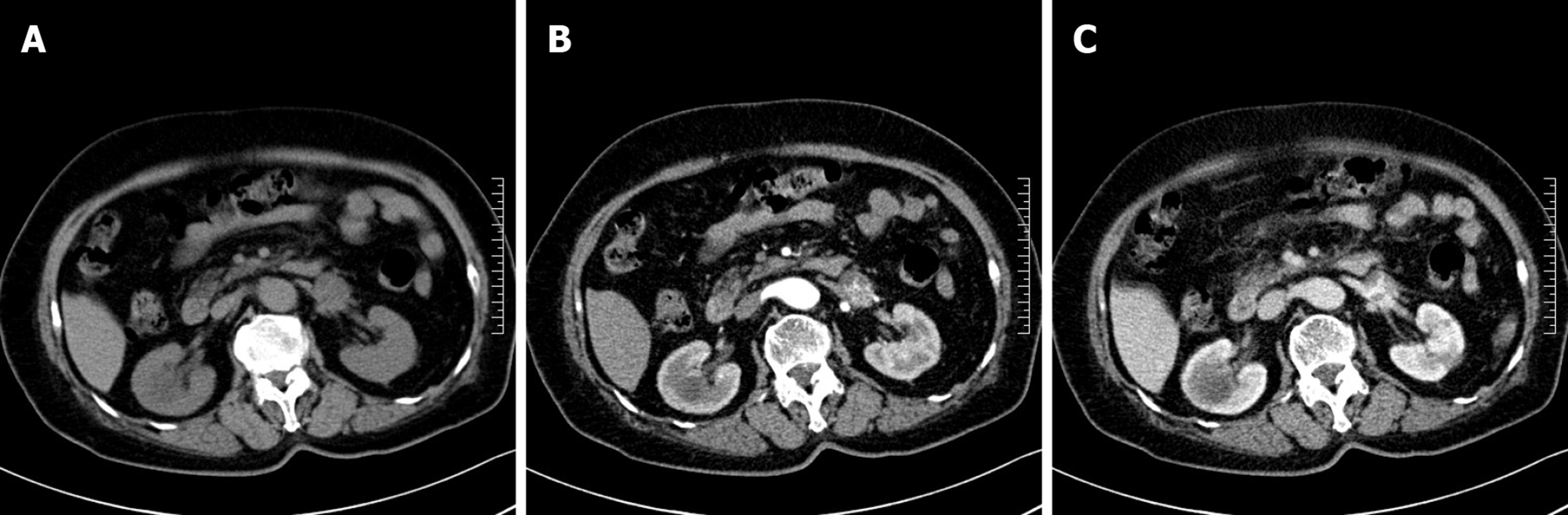

A CT scan of the abdomen was performed in our hospital, on which the neoplasm presented as a circular heterogeneous hypodense soft-tissue shadow (Figure 1A). On contrast-enhanced CT, the neoplasm presented heterogeneous septal enhancement in the arterial phase (Figure 1B) and persistent enhancement in the portal phase, and its boundary with the left renal vein was ill-defined (Figure 1C).

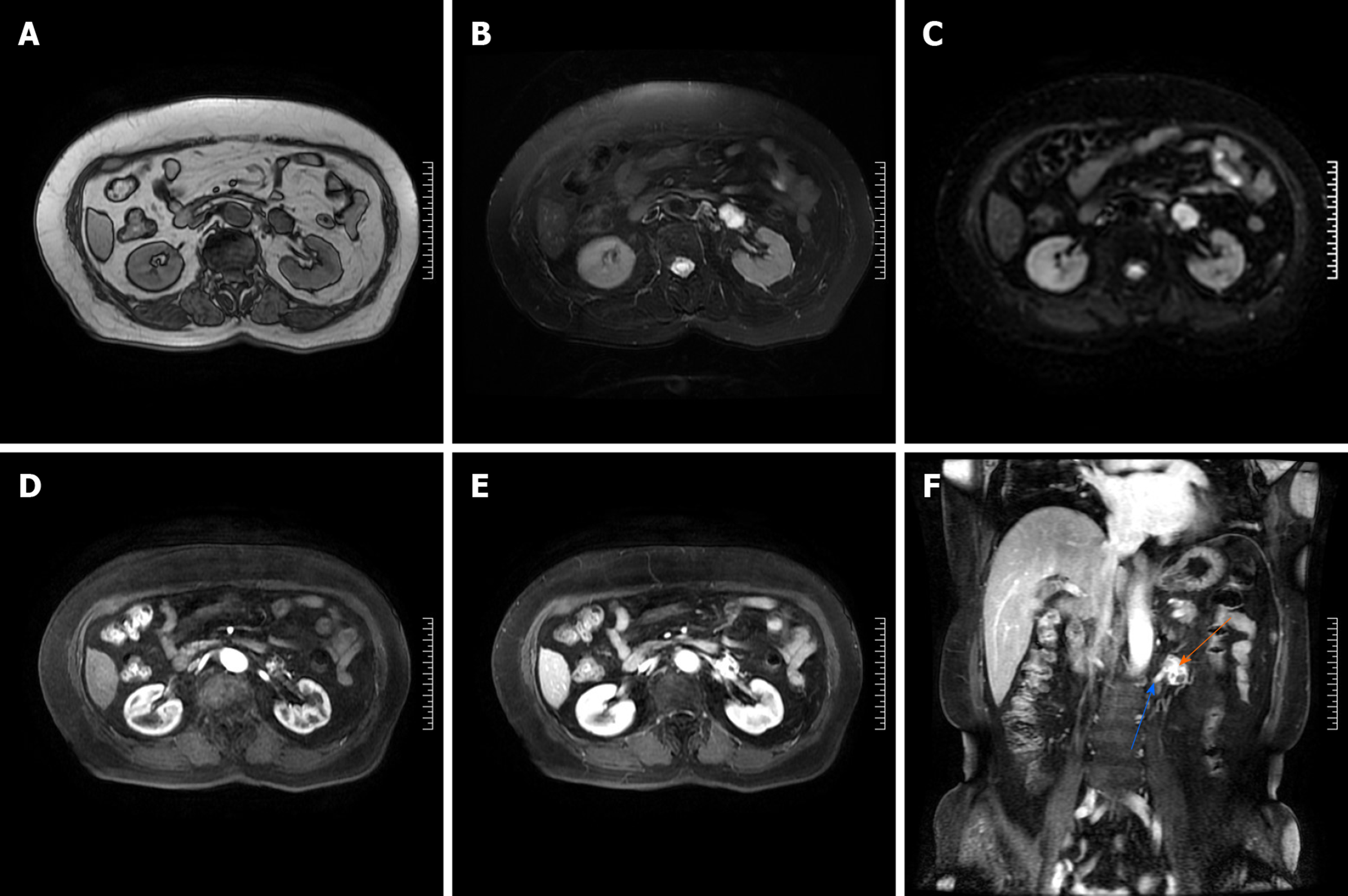

To further clarify the diagnosis, we also performed a contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. On T1-weighted images, the neoplasm showed a circular heterogeneous hypointensity (Figure 2A). On T2-weighted images and diffusion-weighted images, the neoplasm showed a circular heterogeneous hyperintensity (Figure 2B and C). On arterial phase post-contrast T1-weighted images, the neoplasm showed obvious septal enhancement (Figure 2D). On axial and coronal portal venous phase post-contrast T1-weighted images, the neoplasm showed persistent enhancement and its boundary with the left renal vein was ill-defined (Figure 2E and F).

Based on these clinical and radiological manifestations, the neoplasm was initially diagnosed as a neurogenic neoplasm of the left retroperitoneum.

The patient planned to undergo laparoscopic resection of the left retroperitoneal neoplasm, but due to the ill-defined boundary between the neoplasm and the left renal vein, massive bleeding occurred during the surgical separation, so the patient was transferred to open surgery. Finally, the neoplasm was completely resected in the case of renal vascular occlusion, and we reconstructed the left renal vein.

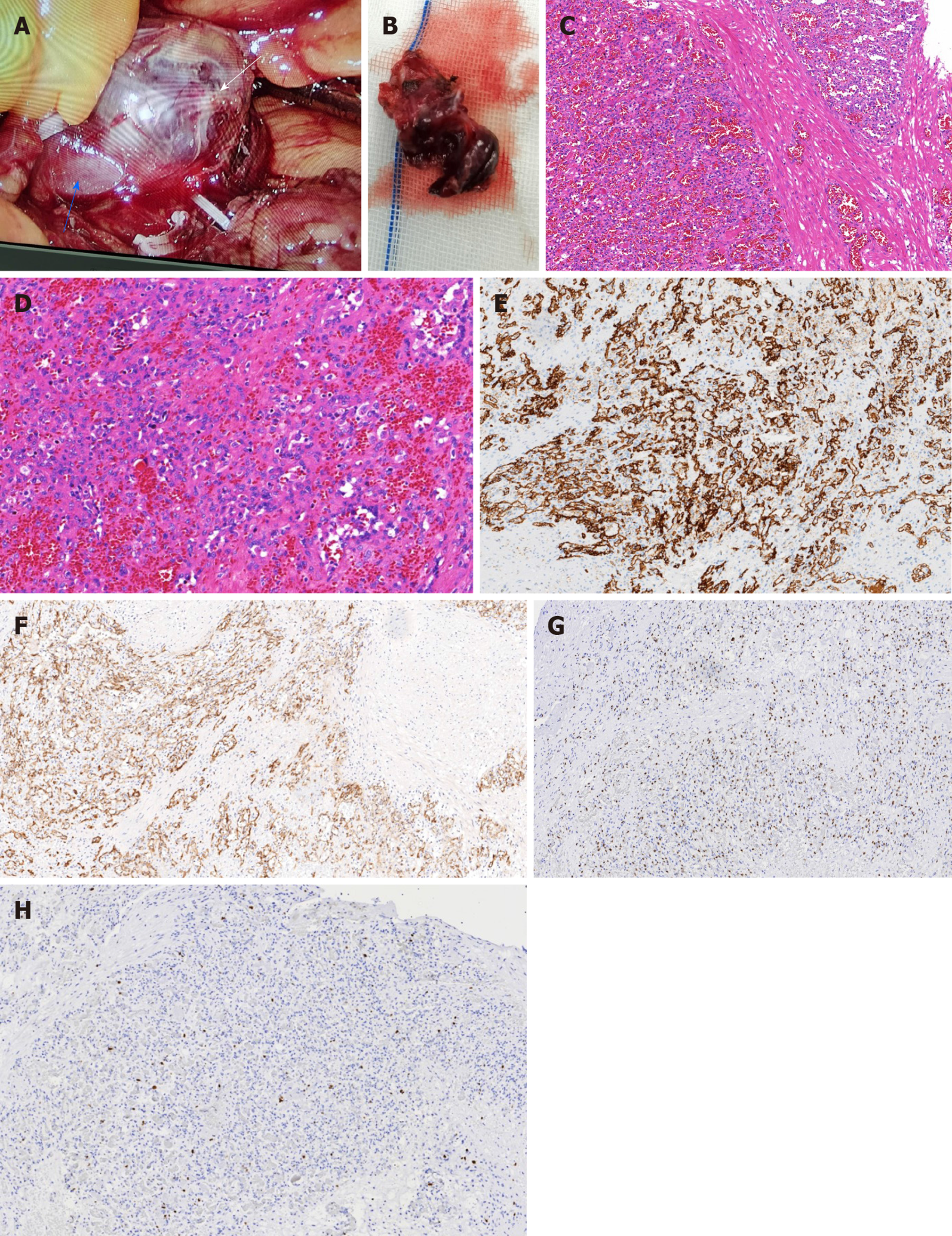

The patient recovered smoothly without any complications. In situ, the neoplasm was located in front of the left renal vein, and the boundary between them was ill-defined (Figure 3A). Macroscopically, the neoplasm presented as a mahogany brown lesion, with no capsule (Figure 3B). Microscopically, the neoplasm was composed of a clear ethmoid, sinusoid, and anastomosing vascular pattern, which was separated by fibers into lobules and had the appearance of the red pulp of the spleen. The vascular endothelial cells of the neoplasm looked like a hobnail, and the local vascular endothelial nuclei were enlarged, hyperchromatic, and slightly abnormal, but no mitotic figure was seen (Figure 3C and D). On immunohistochemical examination, the cytoplasm of the vascular endothelial cells were positive for CD31 (Figure 3E) and CD34 (Figure 3F), and the nuclei of the vascular endothelial cells were positive for ERG (Figure 3G), while only a few endothelial cells were positive for Ki 67 with a positive rate of 7% (Figure 3H). These characteristics were consistent with a diagnosis of AH. There were no signs of postoperative recurrence during the 2-mo CT follow-up.

AH is extremely rare, and its etiology and pathogenesis remain unclear. It mainly occurs in the genitourinary tract; however, several cases have been reported in the liver, gastrointestinal tract, retroperitoneum, nasal cavity, and even the intracranial space[3,4,8,9]. Although AH involving the left renal vein branches has also been reported[10], we presented the first case of isolated anastomotic hemangioma arising from the left renal vein rather than the renal parenchyma.

AH is more common in middle-aged and elderly people, with a slight male predilection[11]. Generally, its diameter ranges from 0.1 cm to 6.0 cm[12]. AH has no special clinical symptoms or laboratory indictors, which is often found on accidental imaging examination. However, the imaging findings of AH show no specificity and are similar to most benign space-occupying lesions. On non-contrast-enhanced CT, the AH showed lobulated lesions, with soft-tissue attenuation, and on contrast-enhanced CT, it presented as a heterogeneous solid lesion with persistent enhancement[11,13]. On non-contrast-enhanced MRI, the AH presented as a round, well-defined T1-hypointense and T2-hyperintense lesion, and on contrast-enhanced MRI, it presented with avid peripheral enhancement in the arterial phase, which persisted in the delayed phase without central enhancement[14]. However, Merritt et al[15] also described the characteristics of their AH on MRI. In their report, the lesion presented as homogenous enhancement in the arterial phase, both peripherally and centrally, which persisted in the delayed phase. In our case, the lesion showed heterogeneous septal enhancement in the arterial phase, which persisted in the portal phase.

The diagnosis of AH mainly depends on histopathological examination. Macroscopically, AH is usually a spongy neoplasm with no capsule, but with a clear boundary and mahogany-brown in color[11,12,16]. Microscopically, AH is characterized by tightly packed capillary channels lined with hobnailed endothelial cells, which are similar in appearance to the red pulp of the spleen, have extramedullary hematopoiesis, and lack endothelial atypia[11,17]. Immunohistochemical staining revealed strong and diffuse CD31, CD34, and EGR positivity[17,18]. It is important to note that there is no mitotic activity, no or slight cellular atypia, and a low Ki-67 index[11,12,18].

AH should be mainly differentiated from angiosarcoma[19]. Angiosarcoma is a rare, invasive, malignant tumor and radiologic examination is unable to differentiate it from AH. Histologically, it also presents with hobnailed endothelial cells and can mimic AH[11]. However, angiosarcoma is characterized by high-grade cell atypia, multiple layers of endothelial cells, and obvious mitotic activity, none of which were present in our case. Therefore, based on these characteristic histopathological findings, our case was diagnosed as AH.

The treatment of AH is controversial because a diagnosis cannot be made from preoperative radiologic examination. When biopsy results are available, the treatment may vary depending on the lesion location, lesion size, and presence of symptoms, such as observation, embolization or radiofrequency ablation, and local or radical resection, to avoid overtreatment. However, some scholars are wary of percutaneous biopsies because of the risk of bleeding in some cases.

AH runs a benign clinical course. Previous studies have shown that there is no propensity for disease recurrence[11,20]. Yet recent research suggests that a recurrence of AH is indeed possible[21] and recurrent GNAQ mutations in the pathogenesis of AH[22]. Although other capillary hemangiomas, especially congenital hemangioma, also have GNAQ mutations, the clinical setting (that is, the age and location of the patient) makes AH unique within this group[22]. Moreover, GNAQ mutations are not found in angiosarcoma, which may play an important role in distinguishing AH from angiosarcoma. Currently, due to the rarity of AH, there are no established guidelines for its follow-up.

We report a case of AH arising from the left renal vein, which, as far as we know, has never been reported before. In light of the lack of specific clinical and radiologic manifestations, AH is easily misdiagnosed preoperatively. Awareness of this entity occurring in the left renal vein will not only help improve doctors' vigilance and reduce the probability of misdiagnosis but also can aid in determining the most appropriate treatment for the patient.

We wish to acknowledge Gang Jin (Urinary Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, Jiaxing) for his assistance in the surgical technique, Ya-Wei Yu (Department of Pathology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, Jiaxing) for her support on this case in pathology, and Xiao-feng Chen (Department of radiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, Jiaxing) for her comments on this case in radiology.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gokce E, Nath J S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Montgomery E, Epstein JI. Anastomosing hemangioma of the genitourinary tract: a lesion mimicking angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1364-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lunn B, Yasir S, Lam-Himlin D, Menias CO, Torbenson MS, Venkatesh SK. Anastomosing hemangioma of the liver: a case series. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:2781-2787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lin J, Bigge J, Ulbright TM, Montgomery E. Anastomosing hemangioma of the liver and gastrointestinal tract: an unusual variant histologically mimicking angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1761-1765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jayaram A, Manipadam MT, Jacob PM. Anastomosing hemangioma with extensive fatty stroma in the retroperitoneum. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2018;61:120-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gunduz M, Hurdogan O, Onder S, Yavuz E. Cystic Anastomosing Hemangioma of the Ovary: A Case Report With Immunohistochemical and Ultrastructural Analysis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:437-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jin LU, Liu J, Li Y, Sun S, Mao X, Yang S, Lai Y. Anastomosing hemangioma: The first case report in the bladder. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4:310-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhou J, Yang X, Zhou L, Zhao M, Wang C. Anastomosing Hemangioma Incidentally Found in Kidney or Adrenal Gland: Study of 10 Cases and Review of Literature. Urol J. 2020; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huang ZY, Chen CC, Thingujam B. Anastomosing Hemangioma of the Nasal Cavity. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:354-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bodman A, Goodman A, Olson JJ. Intracranial thrombosed anastomosing hemangioma: Case report. Neuropathology. 2020;40:206-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Omiyale AO, Golash A, Mann A, Kyriakidis D, Kalyanasundaram K. Anastomosing Haemangioma of the Kidney Involving a Segmental Branch of the Renal Vein. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:927286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Omiyale AO. Anastomosing hemangioma of the kidney: a literature review of a rare morphological variant of hemangioma. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tao LL, Dai Y, Yin W, Chen J. A case report of a renal anastomosing hemangioma and a literature review: an unusual variant histologically mimicking angiosarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silva MA, Fonseca EKUN, Yamauchi FI, Baroni RH. Anastomosing hemangioma simulating renal cell carcinoma. Int Braz J Urol. 2017;43:987-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Peng X, Li J, Liang Z. Anastomosing haemangioma of liver: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7:507-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Merritt B, Behr S, Umetsu SE, Roberts J, Kolli KP. Anastomosing hemangioma of liver. J Radiol Case Rep. 2019;13:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Al-Maghrabi HA, Al Rashed AS. Challenging Pitfalls and Mimickers in Diagnosing Anastomosing Capillary Hemangioma of the Kidney: Case Report and Literature Review. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:255-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cheon PM, Rebello R, Naqvi A, Popovic S, Bonert M, Kapoor A. Anastomosing hemangioma of the kidney: radiologic and pathologic distinctions of a kidney cancer mimic. Curr Oncol. 2018;25:e220-e223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | O'Neill AC, Craig JW, Silverman SG, Alencar RO. Anastomosing hemangiomas: locations of occurrence, imaging features, and diagnosis with percutaneous biopsy. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41:1325-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Heidegger I, Pichler R, Schäfer G, Zelger B, Zelger B, Aigner F, Bektic J, Horninger W. Long-term follow up of renal anastomosing hemangioma mimicking renal angiosarcoma. Int J Urol. 2014;21:836-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang W, Wang Q, Liu YL, Yu WJ, Liu Y, Zhao H, Zhuang J, Jiang YX, Li YJ. Anastomosing hemangioma arising from the kidney: a case of slow progression in four years and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2208-2213. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Burton KR, Jakate K, Pace KT, Vlachou PA. A case of recurrent, multifocal anastomosing haemangiomas. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017220076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bean GR, Joseph NM, Gill RM, Folpe AL, Horvai AE, Umetsu SE. Recurrent GNAQ mutations in anastomosing hemangiomas. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:722-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |