Published online Oct 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4946

Peer-review started: July 12, 2020

First decision: August 8, 2020

Revised: August 21, 2020

Accepted: September 10, 2020

Article in press: September 10, 2020

Published online: October 26, 2020

Processing time: 105 Days and 20.2 Hours

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare but life-threatening disorder, characterized by a hyperimmune response. The mortality is high despite progress being made in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. HLH is traditionally divided into primary (familial or genetic) and secondary (reactive) according to the etiology. Secondary HLH (sHLH), more common in adults, is often associated with underlying conditions including severe infections, malignancies, autoimmune diseases, or other etiologies.

The case involves a 31-year-old woman, presented with a high persistent fever, rash, and splenomegaly. She met the diagnostic criteria of the HLH-2004 guideline and thus was diagnosed with HLH, with positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and positive cytomegalovirus (CMV)-DNA. The patient responded well to a combination of immunomodulatory, chemotherapy, and supportive treatments. When her PCR evaluation for CMV turned negative, her serum ferritin also dropped significantly. Her clinical symptoms improved dramatically, and except for ANA, the abnormal laboratory findings associated with HLH returned to normal. Our previous study has shown that the median overall survival of HLH patients is only 6 mo; however, our patient has been cured and has not presented with any relapse of the disease for 6 years.

This case emphasizes that thorough early removal of the CMV infection is significant for the prognosis of this HLH patient.

Core Tip: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare immune-mediated life-threatening disease. Active HLH develops rapidly, and the mortality rate is high if reasonable and effective interventions are not promptly undertaken. Herein, we report a case of a 31-year-old Chinese woman diagnosed with systemic autoimmune abnormalities complicated by cytomegalovirus (CMV)-induced HLH. The patient has been cured and has not relapsed for 6 years. This report may act as a reference for HLH therapy in cases positive for anti-nuclear antibody and CMV.

- Citation: Miao SX, Wu ZQ, Xu HG. Systemic autoimmune abnormalities complicated by cytomegalovirus-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(20): 4946-4952

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i20/4946.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4946

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), a hyperinflammatory disorder, is characterized by uncontrolled immune cell activation and excessive production of inflammatory cytokines. The continued production of cytokines leads to a dramatic cytokine storm and severe multiorgan injury[1-3]. Secondary HLH (sHLH) is often associated with a variety of underlying conditions[4], with nearly one-third of the reported cases in adults having more than one underlying cause[5]. Here, we report a case of systemic autoimmune abnormalities, complicated by cytomegalovirus (CMV)-induced HLH. The patient’s symptoms and laboratory abnormalities improved dramatically once PCR for CMV-DNA turned negative. The patient recovered and did not present any relapse of the HLH for 6 years.

A 31-year-old woman presented with high fever (38.5 °C) and a rash lasting more than 15 d.

The patient was admitted to the Department of Infectious Diseases of our hospital with fever and rash on March 27, 2013. The high fever started half a month earlier, with a peak of 40.5 °C, and was not alleviated after taking medications. She visited a hospital, and laboratory results indicated a total white blood cell (WBC) count of 14.92 × 109/L, C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 54.4 mg/L, serum ferritin (SF) level of 1534 ng/mL, and serum albumin (ALB) level of 32.1 g/L. She was initially treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics including moxifloxacin hydrochloride, cefoperazone sodium, and sulbactam sodium. The duration and specific dosage of the drugs are not known. The treatment resulted in only minimal improvement in her symptoms. She was referred to our hospital for further care.

The patient reported a history of one normal pregnancy. She denied any history of chronic illness, infectious diseases, surgical procedures, or drug allergies.

Upon admission, the patient’s temperature was 38.5 °C, heart rate was 72 beats/min, and blood pressure was 122/79 mmHg. A skin rash covered her neck. Lympha-denopathy was not observed.

Laboratory findings on admission revealed a rise in WBC (22.22 × 109/L), absolute neutrophil count (ANC) (20.66 × 109/L), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (78 mm/h), CRP (96 mg/L), and SF (1300.9 ng/mL). The level of serum calcium (CA) dropped (2.01 mmol/L). Indicators of her liver function also showed abnormalities: Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 55.8 U/L and ALB 31.5 g/L. The patient tested positive for anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) (titer higher than 1:320), although other antibodies including anti-ribonucleoprotein antibody, anti-SS-A antibody, anti-DNA antibody, anti-Smith antibody, and antiphospholipid antibody were negative.

Splenomegaly was observed on abdominal computed tomographic images.

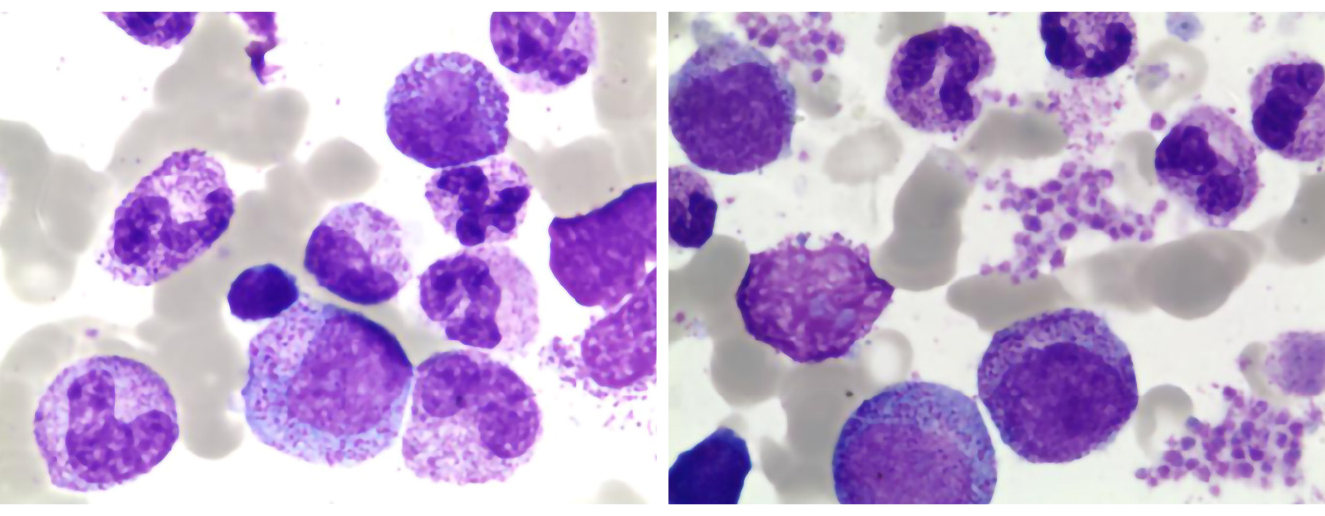

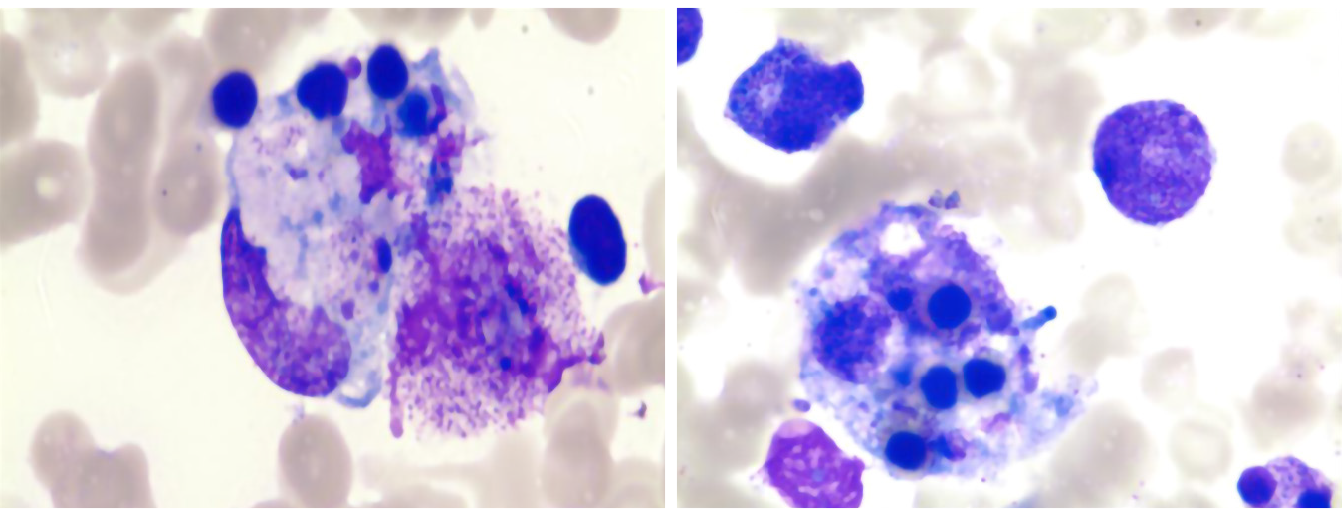

After 5 d of anti-infective treatment, the patient’s temperature increased, peaking at 40.8 °C. To investigate the persistent high fever cause, the patient underwent a bone marrow aspiration on the 7th d from admission (day 7). It generally showed normal features without significant hemophagocytosis (Figure 1). On day 14, she developed severe pancytopenia, with hemoglobin (HB) 78 g/L and a platelet count (PLT) of 16 × 109/L. Laboratory evaluation showed low level of fibrinogen (0.3 g/L), an increase in SF (> 1500 ng/mL), and high D-dimer (> 40 mg/L). To further confirm the diagnosis, we performed a second bone marrow aspiration, which revealed elevated blood cell phagocytosis (Figure 2). Subsequent PCR evaluation found CMV-DNA at a concentration of 1.74 × 103/mL, indicating the presence of systemic CMV infection.

With high fever, splenomegaly, pancytopenia (HB 78 g/L, PLT 16 × 109/L), hyperferritinemia (> 1500 ng/mL), hypertriglyceridemia (fasting, 13.08 mmol/L), hypofibrinogenemia (0.3 g/L), and hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, the patient met the diagnostic criteria for HLH according to the HLH-2004 guidelines (Table 1)[6].

| Diagnostic criteria for HLH fulfilled, at least 5 of the 8 criteria below | First admission | Post-treatment | Second admission | Third admission |

| Fever | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Splenomegaly | Y | N | N | N |

| Cytopenia, affecting 2 of 3 lineages in the peripheral blood | Y | N | N | N |

| Hemoglobin < 9 g/dL | Y | N | N | N |

| Platelets < 100 × 109/L | Y | N | N | N |

| Neutrophils < 1.0 × 109/L | Y | N | N | N |

| Hypertriglyceridemia (fasting ≥ 3.0 mmol/L) and/or hypofibrinogenemia (≤ 150 mg/dL) | Y | N | N | N |

| Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow or spleen or lymph nodes (no evidence of malignancy) | Y | NA | NA | NA |

| Low or absent natural killer cell activity | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ferritin ≥ 500 ng/mL | Y | N | N | N |

| Soluble cluster of differentiation 25 (i.e. soluble interleukin 2 receptor) ≥ 2400 U/mL | NA | NA | NA | NA |

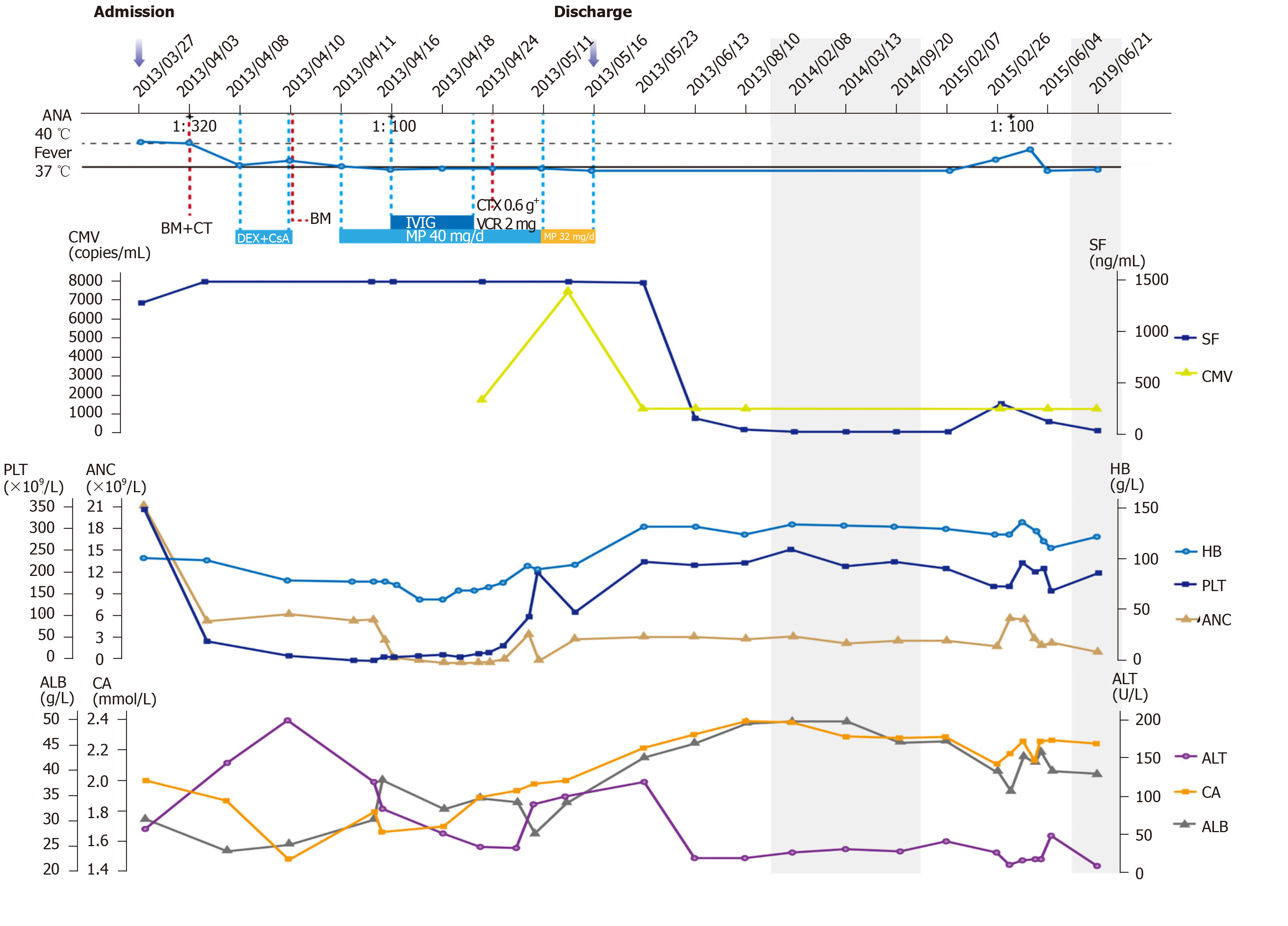

Initially, the patient received broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy at the local hospital with no noticeable effect. After admission and extensive medical examination, the patient was diagnosed with HLH, induced by systemic autoimmune abnormalities. She was treated with dexamethasone (DEX) and cyclosporine A (CsA) for 3 d. However, her temperature remained around 38 °C. Then she was transferred to the Department of Hematology for further treatment. Methylprednisolone was maintained at 40 mg/d for 1 mo. The dose was reduced to 32 mg/d for 6 d. Along with methylprednisolone therapy, intravenous polyvalent immune globulin (IVIG) was administered for 6 d. Supportive treatment consisted of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor that was used for the severe neutropenia, antibiotics adjusted to deal with systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and platelet and cryoprecipitate transfusions for coagulation dysfunction. These treatments were effective. When the patient’s temperature returned to normal, she was started on a chemotherapy regimen with cyclophosphamide and vincristine (Figure 3).

The patient was discharged after her symptoms and laboratory abnormalities improved, and she felt better. She was readmitted twice for fever caused by an autoimmune disease on February 26, 2015 and June 3, 2015 (Figure 3). Based on the results of her laboratory tests, the physician ruled out systemic lupus erythematosus. Her symptoms were relieved after anti-inflammatory and glucocorticoid treatment. The patient was treated with no relapse for 6 years.

In this study, we have reported a case of systemic autoimmune abnormality complicated by CMV-induced HLH, which was successfully treated. The case was characterized by a notable improvement in the patient’s symptoms and laboratory abnormalities (ANC, HB, PLT, ALT, ALB, and CA, but not ANA) once the PCR for CMV-DNA became negative. There was no evidence of HLH recurrence for 6 years.

In an analysis of data from January 1974 to September 2011 of 2197 adult patients diagnosed with HLH in whom the causes were identified, the disease was related to autoimmune abnormalities in only 12.56% of the patients. Of these, systemic autoimmune diseases accounted for 48%[5]. Fukaya et al[7] analyzed 30 HLH cases related to systemic autoimmune diseases. They found that 27% of them (8/30) were diagnosed with infection-associated HLH, and the mortality rate among them was 63% (5/8). The patient in our case was initially treated with empirical antibiotics that were ineffective. When she was considered to have HLH induced by systemic autoimmune abnormalities, treatment with DEX, CsA, methylprednisolone, and IVIG was initiated. The combination of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants was found to be more effective than corticosteroids alone when treating autoimmune-associated HLH[8]. The patient responded well to these treatments, but still had occasional fever. She was found to have CMV infection in a subsequent laboratory test.

CMV, a member of the herpes virus family, is a known infective agent among children and immunosuppressed patients. There have been reports of HLH induced by CMV infection following pediatric orthotopic liver transplantation and during thiopurine immunosuppressive therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease[9-11]. CMV-related HLH can also be seen during the course of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and adult-onset Still’s disease[12,13]. Based on these reports, CMV infection is thought to be reactivated to trigger HLH. Because our HLH patient was positive for ANA but was not tested for CMV at the first diagnostic effort, it is impossible to speculate whether she was in an immuno-suppressive state that caused the CMV infection to revive and stimulate HLH, or whether CMV infection was a primary infection that was one of the triggers of HLH. After combined immunomodulatory, chemotherapy, and supportive treatments, the patient had a complete response, and CMV was tested negative. There was no evidence of HLH relapse for 6 years (Table 1).

There are no prospective trials to guide HLH treatment in adults due to the complex diversity of the underlying diseases, triggers, and associated symptoms[14]. Our patient eventually recovered after treatment based on the HLH-2004 protocol[6], our clinical experience, and expert opinion. The patient was initially diagnosed with HLH induced by systemic autoimmune abnormalities and was thus treated with DEX, CsA, methylprednisolone, and IVIG. Considering that the patient did not have Epstein-Barr virus infection-related or lymphoma-associated HLH, etoposide was not used[3]. Glucocorticoid drugs are predominantly included in initial regimens when treating HLH, regardless of the underlying etiology[5,15]. CsA is usually used in patients with suspected HLH diagnosis to increase immunosuppression without inducing additional myelotoxicity[16]. IVIG therapy, first proposed by Freeman et al[17] for virus-associated HLH treatment, is often effective in patients diagnosed with HLH in the context of infectious and autoimmune diseases[18]. A growing body of data supports the therapeutic effectiveness of IVIG in patients with different causes of HLH[19,20].

A very high SF level, one of the diagnostic parameters for HLH, was reported to be a major marker when differentiating between HLH and other systemic processes[21,22]. A recent retrospective observational study of 229 adult HLH patients showed that SF level could be used as an independent prognostic marker in these patients, regardless of the underlying etiology[23]. After treatment, the patient’s SF level decreased from > 1500 ng/mL to 144.6 ng/mL and did not exceed 500 ng/mL in subsequent tests (Figure 3). CRP is elevated in 80%-90% of HLH patients, especially in the early stages[24], consistent with our results (not shown). Gao et al[25] demonstrated that ALB and CA levels increase with the recovery from the disease, which was confirmed in our case (Figure 3). This may be the result of a variety of factors, including increased albumin production after liver function recovery, decreased albumin consumption after the disease has improved, and because ALB is a negative acute-phase reactant that decreases with inflammation and normalizes upon recovery. The prognosis of autoimmune- and infection-related HLH is better than other etiologies[26]. This is supported by our patient, who was successfully cured and had not relapsed through 6 years of follow-up (Table 1).

Our study had some limitations. First, we did not check nature killer cell activity and soluble CD25 (i.e. soluble interleukin 2 receptor). These are not routine tests, and it is difficult to rely on them to determine HLH diagnosis, as it occurs at an extremely low incidence rate. Second, comprehensive screening for viral causes of HLH was not performed in the early stages of diagnosis.

In summary, we report a case of HLH caused by systemic autoimmune abnormalities and CMV infection. The patient was successfully treated with a combination of immunomodulatory, chemotherapy, and supportive treatments. This case suggests that through early screening, timely treatment aimed at removing the infection (CMV infection in our case) and inhibition of the inflammatory response, along with supportive therapy, are of great significance for the prognosis of HLH patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El-Karaksy H S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor:Ma YJ

| 1. | Canna SW, Marsh RA. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2020;135:1332-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 57.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zinter MS, Hermiston ML. Calming the storm in HLH. Blood. 2019;134:103-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, von Bahr Greenwood T, Machowicz R, Berliner N, Birndt S, Gil-Herrera J, Girschikofsky M, Jordan MB, Kumar A, van Laar JAM, Lachmann G, Nichols KE, Ramanan AV, Wang Y, Wang Z, Janka G, Henter JI. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133:2465-2477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 105.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bergsten E, Horne A, Aricó M, Astigarraga I, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Ishii E, Janka G, Ladisch S, Lehmberg K, McClain KL, Minkov M, Montgomery S, Nanduri V, Rosso D, Henter JI. Confirmed efficacy of etoposide and dexamethasone in HLH treatment: long-term results of the cooperative HLH-2004 study. Blood. 2017;130:2728-2738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383:1503-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 788] [Cited by in RCA: 951] [Article Influence: 86.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in RCA: 3573] [Article Influence: 198.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Fukaya S, Yasuda S, Hashimoto T, Oku K, Kataoka H, Horita T, Atsumi T, Koike T. Clinical features of haemophagocytic syndrome in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases: analysis of 30 cases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1686-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kumakura S, Murakawa Y. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of autoimmune-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in adults. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2297-2307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hardikar W, Pang K, Al-Hebbi H, Curtis N, Couper R. Successful treatment of cytomegalovirus-associated haemophagocytic syndrome following paediatric orthotopic liver transplantation. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:389-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van Langenberg DR, Morrison G, Foley A, Buttigieg RJ, Gibson PR. Cytomegalovirus disease, haemophagocytic syndrome, immunosuppression in patients with IBD: 'a cocktail best avoided, not stirred'. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:469-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Koketsu S, Watanabe T, Hori N, Umetani N, Takazawa Y, Nagawa H. Hemophagocytic syndrome caused by fulminant ulcerative colitis and cytomegalovirus infection: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1250-3; discussion 1253-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Amenomori M, Migita K, Miyashita T, Yoshida S, Ito M, Eguchi K, Ezaki H. Cytomegalovirus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in a patient with adult onset Still's disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:100-102. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Sakamoto O, Ando M, Yoshimatsu S, Kohrogi H, Suga M, Ando M. Systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by cytomegalovirus-induced hemophagocytic syndrome and colitis. Intern Med. 2002;41:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schram AM, Berliner N. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the adult patient. Blood. 2015;125:2908-2914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Balis FM, Lester CM, Chrousos GP, Heideman RL, Poplack DG. Differences in cerebrospinal fluid penetration of corticosteroids: possible relationship to the prevention of meningeal leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Imashuku S, Hibi S, Kuriyama K, Tabata Y, Hashida T, Iwai A, Kato M, Yamashita N, Oda MUchida M, Kinugawa N, Sawada M, Konno M. Management of severe neutropenia with cyclosporin during initial treatment of Epstein-Barr virus-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;36:339-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen RL, Lin KH, Lin DT, Su IJ, Huang LM, Lee PI, Hseih KH, Lin KS, Lee CY. Immunomodulation treatment for childhood virus-associated haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 1995;89:282-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, Filipovich AH, McClain KL. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011;118:4041-4052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 747] [Cited by in RCA: 793] [Article Influence: 56.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Simon DW, Aneja R, Carcillo JA, Halstead ES. Plasma exchange, methylprednisolone, IV immune globulin, and now anakinra support continued PICU equipoise in management of hyperferritinemia-associated sepsis/multiple organ dysfunction syndrome/macrophage activation syndrome/secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:486-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hot A, Madoux MH, Viard JP, Coppéré B, Ninet J. Successful treatment of cytomegalovirus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome by intravenous immunoglobulins. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:159-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schram AM, Campigotto F, Mullally A, Fogerty A, Massarotti E, Neuberg D, Berliner N. Marked hyperferritinemia does not predict for HLH in the adult population. Blood. 2015;125:1548-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Allen CE, Yu X, Kozinetz CA, McClain KL. Highly elevated ferritin levels and the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1227-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhou J, Zhou J, Shen DT, Goyal H, Wu ZQ, Xu HG. Development and validation of the prognostic value of ferritin in adult patients with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Switala JR, Hendricks M, Davidson A. Serum ferritin is a cost-effective laboratory marker for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the developing world. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:e89-e92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gao X, Qiu HX, Wang JJ, Song M, Duan LM, Tian T. [Clinical significance of serum calcium and albumin in patients with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2017;38:1031-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Huang W, Wang Y, Wang J, Zhang J, Wu L, Li S, Tang R, Zeng X, Chen J, Pei R, Wang Z. [Clinical characteristics of 192 adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2014;35:796-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |