Published online Jan 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i2.471

Peer-review started: October 25, 2019

First decision: December 4, 2019

Revised: December 5, 2019

Accepted: December 22, 2019

Article in press: December 22, 2019

Published online: January 26, 2020

Processing time: 84 Days and 0.3 Hours

Penetrating brain injury (PBI) is an uncommon emergency in neurosurgery, and transorbital PBI is a rare type of PBI. Reasonable surgical planning and careful postoperative management can improve the prognosis of patients

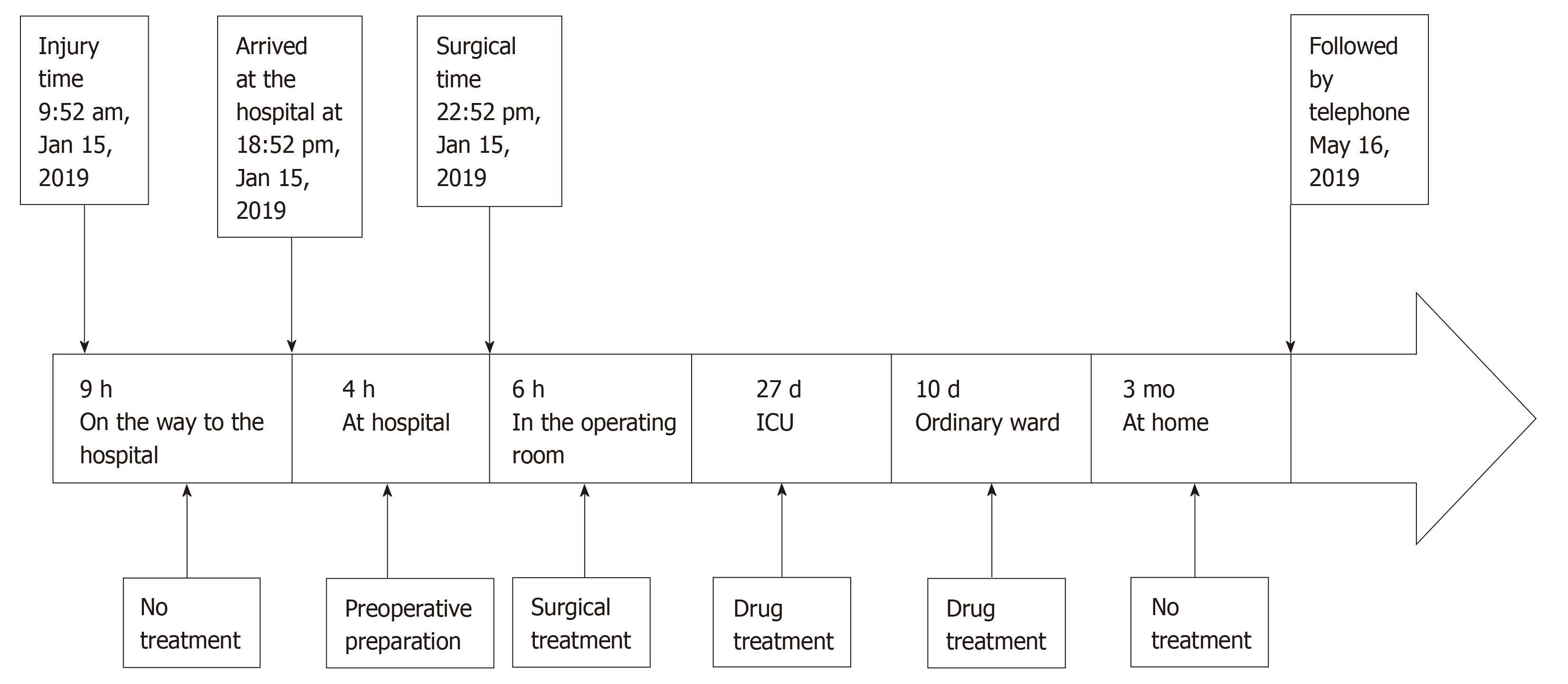

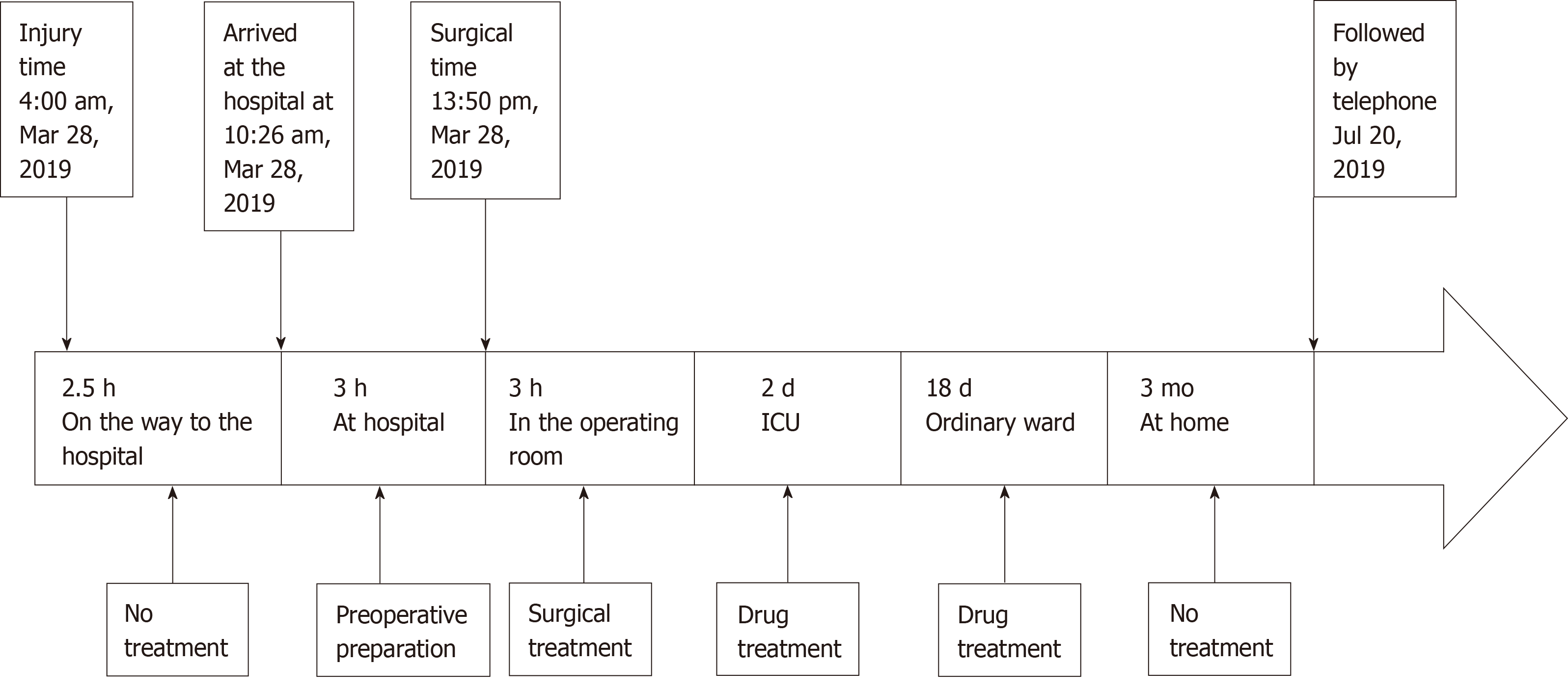

The first case is a 68-year-old male patient who was admitted to the hospital because a branch punctured his brain through the orbit for approximately 9 h after he unexpectedly fell while walking. After admission, the patient underwent emergency surgical treatment and postoperative anti-infection treatment. The patient was able to follow instructions at a 4-mo follow-up review. The other case is a 46-year-old male patient who was admitted to the hospital due to an intraorbital foreign body caused by a car accident, after which the patient was unconscious for approximately 6 h. After admission, the patient underwent emergency surgical treatment and postoperative anti-infection treatment. The patient could correctly answer questions at a 3-mo follow-up review.

Transorbital PBI is a rare and acute disease. Early diagnosis, surgical intervention, and application of intravenous antibiotics can improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients.

Core tip: Transorbital penetrating brain injury is a rare and acute disease. Early diagnosis, surgical intervention and application of intravenous antibiotics can improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients.

- Citation: Xue H, Zhang WT, Wang GM, Shi L, Zhang YM, Yang HF. Transorbital nonmissile penetrating brain injury: Report of two cases. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(2): 471-478

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i2/471.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i2.471

Penetrating brain injury (PBI) is an uncommon emergency in neurosurgery, and transorbital PBI is a rare type of PBI. It is more often reported in the military, where it is often associated with bullets or other blasting fragments, and is comparatively rare in civilians. Computed tomography (CT), with its simple operation and quick acquisition of results, is the first choice for the examination of transorbital PBI. The surgical approaches of these diseases are divided into a transorbital approach and a transcranial approach.

In this report, we present two cases of transorbital nonmissile PBI, with an aim to demonstrate certain general management principles of this kind of disease which can improve patient outcomes.

Case 1: A 68-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital because a branch punctured his brain through the orbit for approximately 9 h after he unexpectedly fell while walking.

Case 2: A 46-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital due to an intraorbital foreign body caused by a car accident, after which the patient was unconscious for approximately 6 hours.

Case 1: The patient fell down accidentally while walking in the morning, which caused the branch to penetrate into the skull from the orbit. He was unconscious immediately after the injury. The patient was sent to the local hospital for treatment by his family. After the local hospital gave symptomatic support treatment, the patient's condition did not improve significantly. His family members came to our hospital for further treatment. The patient vomited frequently during the course of the illness.

Case 2: The patient suffered a car accident that caused steering wheel fragments to penetrate the skull from the orbit. He was delirious and complained of severe headache. He was taken by ambulance to our hospital and admitted. There was no vomiting or convulsion in the course of the disease.

Case 1: The patient had an abnormal left pupil due to previous left-eye trauma.

Case 2: The patient was previously healthy.

Cases 1 and 2: The patients had a free personal and family history.

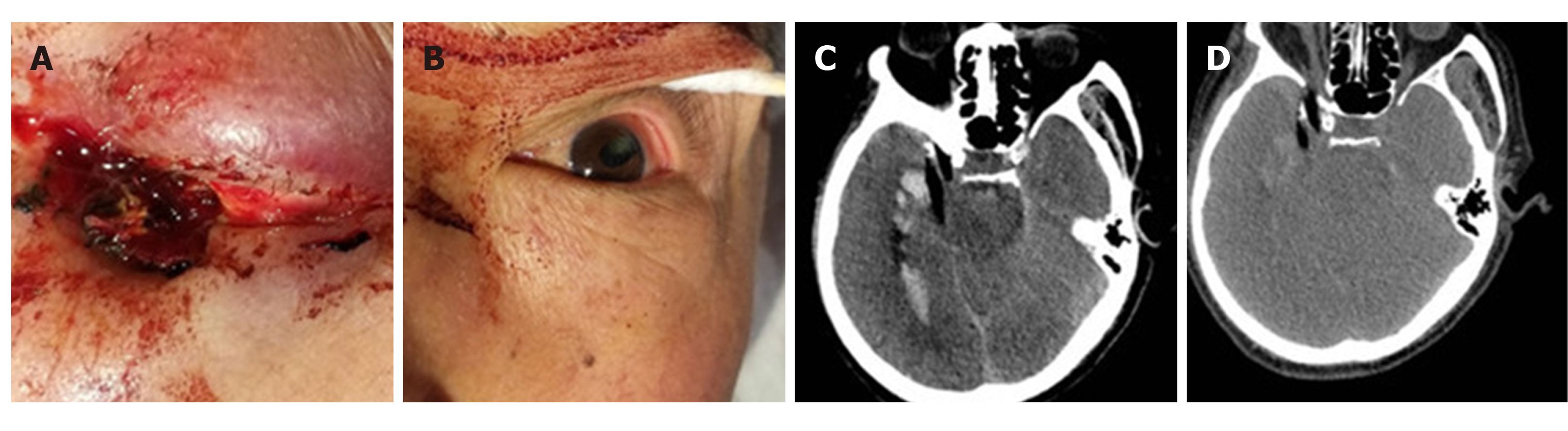

Case 1: Physical examination revealed an exposed wooden foreign body, 0.8 cm in diameter, in the right inferior orbital wall accompanied by blood exudation (Figure 1A). The left pupil was elliptic, with a long diameter of 5.0 mm and a short diameter of 3.0 mm (Figure 1B). The left pupil was directly and indirectly insensitive with regard to the pupillary light reflex. The muscle strength of the left limb was grade 1, while the muscle strength of the right limb was grade 5.

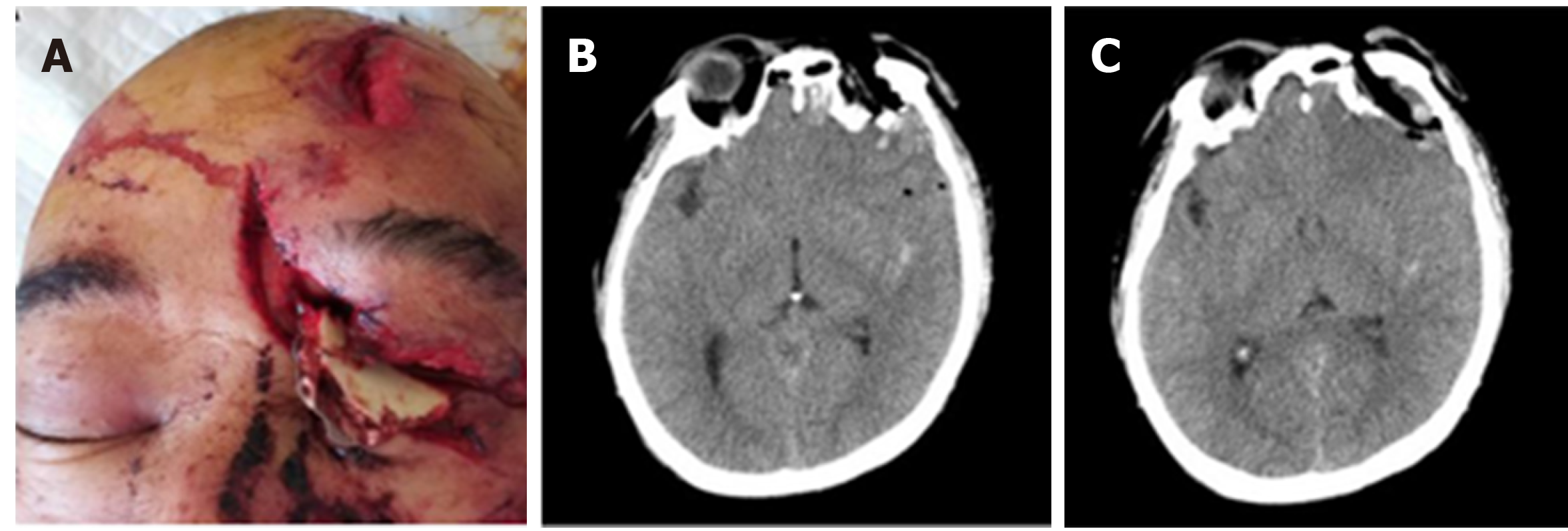

Case 2: Physical examination showed a bone-plate-like foreign body in the left orbit that penetrated into the skull, with a fractured end exposed (Figure 2A). The muscle strength of the upper limbs was grade 3, while the muscle strength of the lower limbs was grade 0. There was sensory disturbance below the level of both breasts.

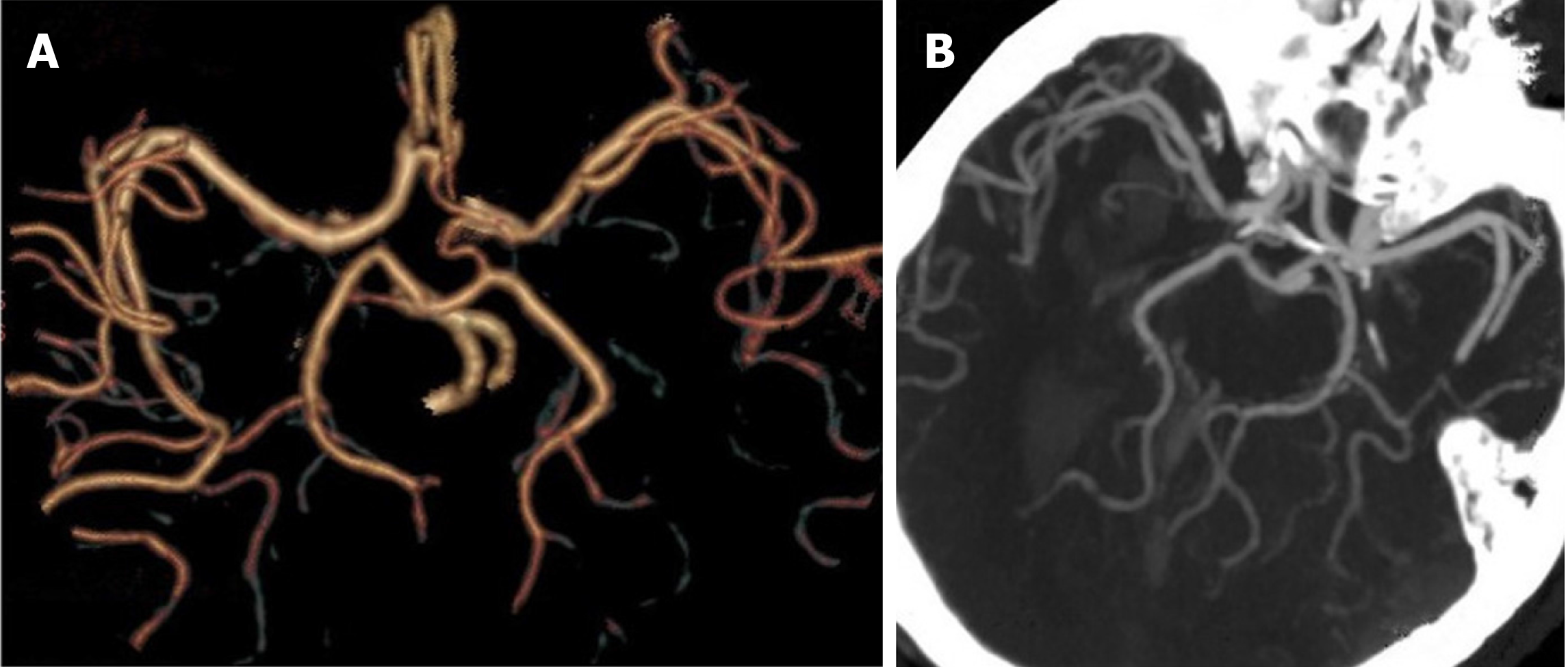

Case 1: Preoperative head CT showed a strip of low-density shadow under the right eyeball, entering the brain through the orbital apex and lateral orbital apex (Figure 1C and D). The optic nerve was compressed. There was no vascular injury visible in the preoperative CT-angiography (CTA) images (Figure 3).

Case 2: Head CT suggested a low-density foreign body penetrating the skull in the left superior orbital wall (Figure 2B and C). Cervical spine CT suggested cervical fracture and dislocation (C6, flexion and distraction type, grade II), cervical disc rupture (C6/7), and cervical spinal cord injury.

The final diagnosis was transorbital nonmissile PBI (Case 1 and Case 2).

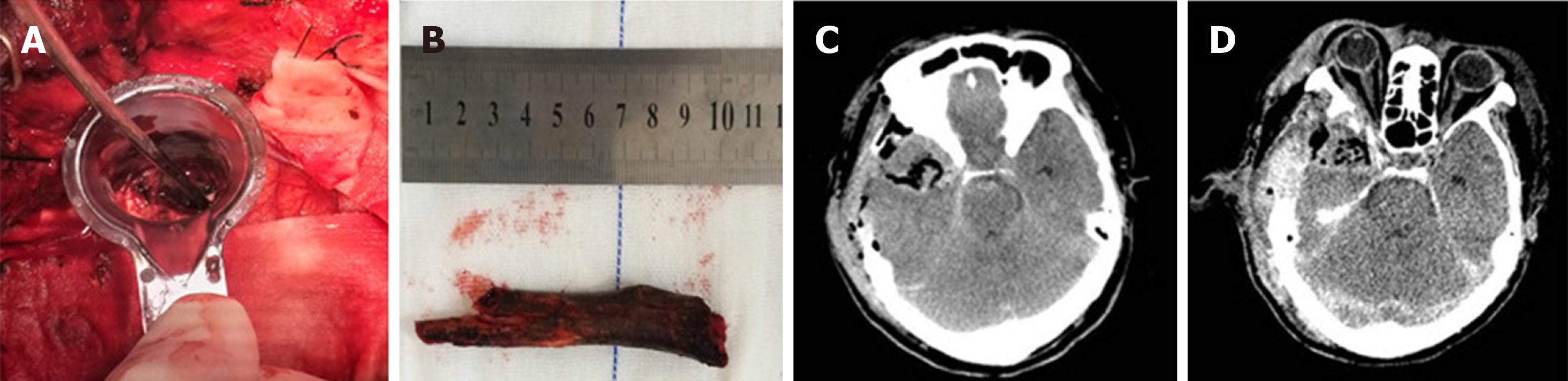

Transcranial craniotomy was performed. A black and brown wooden foreign body was embedded in the brain tissue to a depth of approximately 1 cm (Figure 4A). The foreign body was removed after removing the necrotic brain tissue and blood clot (Figure 4B). A head CT review showed complete removal of the foreign body without secondary bleeding (Figure 4C and D). After the operation, the patient was given vancomycin combined with meropenem to control infection.

Transcranial craniotomy was carried out to remove the necrotic frontal lobe and expose the end of the foreign body (Figure 5A). The foreign body was then slowly removed from the orbital region (Figure 5B), and the skull base was tightly repaired. A head CT review showed complete removal of the foreign body without secondary bleeding (Figure 5C and D). The patient was given meropenem after the operation to control infection, and when his condition was stable, the patient was transferred to a spinal surgery unit for surgical treatment.

The patient could answer basic questions at a 4-mo follow-up review but had a limb-movement disorder.

The patient exhibited clear consciousness at a postoperative 3-mo review, but a movement disorder of the bilateral lower limbs and sensory disorders below the level of both breasts were still present.

PBI is an uncommon emergency in neurosurgery, accounting for 0.4% of craniocerebral injuries[1]. Transorbital nonmissile PBI is a rare type of PBI. It is more often reported in the military, where it is often associated with bullets or other blasting fragments, and is comparatively rare in civilians[2]. In nonwar years, it can be caused by foreign bodies penetrating the skull in traffic accidents or by individuals accidentally falling on sharp objects (pencils, branches, etc.), and it can also result from fights[3,4]. The foreign bodies also vary greatly, with cases involving chopsticks[5], metal rods[6], bicycle spokes[7], ball-point pens[8], bamboo[9], scissors[10], electric toothbrushes[11], twigs[2,12], and blades[12]. The pathogenic foreign bodies involved in the cases reported in the present paper were a branch in one case and a plastic fragment of the steering wheel in the other. A pathogenic foreign body of the type involved in the second case has not been previously reported in the international literature and is therefore reported here for the first time. Misdiagnosis is likely in cases involving this type of foreign body because it has a similar appearance to that of a bone plate, so it requires special attention from clinicians.

The bone orbit is a funnel-shaped anatomical structure with relatively weak sclerotin[5]. Foreign bodies with a length of more than 5 cm can penetrate the cranial cavity through the orbit[13]. The pathogenic foreign bodies reported in this paper were both longer than 5 cm, and both penetrated the brain. Foreign bodies enter the brain through three main routes, namely, the orbital roof, inferior orbital fissure, and optic canal[2]. The extremely weak bone of the orbital roof makes it the most common route by which foreign bodies enter the brain, often resulting in frontal lobe damage[5]. The foreign body in the second case reported in this paper entered by this route, which caused frontal lobe and frontal sinus damage. Although there was no loss of important anatomical sites, the skull base required careful and precise intraoperative repair because damage to the skull base and frontal sinus is prone to intracranial infection. The second route of cranial penetration is horizontal crossing of the supraorbital fissure, which can result in penetration of the brain stem and has a very high fatality rate[14]. Although the brain stem was not directly injured in the first case presented in this paper, the intraoperative procedures were performed with strict caution to prevent brain stem injury because the anatomical position was extremely close to the brain stem. The last common route of cranial penetration is through the optic nerve canal and is often accompanied by severe visual impairment[6].

Plain X-ray film can easily detect metal foreign bodies, but diagnosing wooden foreign bodies is difficult[15]. CT, with its simple operation and quick acquisition of results, is the first choice for the examination of orbital PBI. However, there are two points to be noted: (1) The imaging artifacts produced by a metal foreign body interfere with the imaging of brain tissue, and dual-source CT (DECT) provides a solution to this problem. DECT has been suggested to reduce metal artifacts and generate higher quality images than CT[16,17]; and (2) newly cut wood has high water content and moderate physical density, so it is difficult to distinguish it from soft tissues, such as muscle and vitreous humor, while dry wood, with low physical density, is difficult to distinguish from adipose tissue and gas. With time, the CT value of a wooden foreign body changes due to its absorption of water from the surrounding tissues[5]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a useful complement to CT examination and helps to distinguish wooden foreign bodies from surrounding tissues[1]. However, MRI examination is strictly prohibited for the examination of metal foreign bodies to avoid secondary brain injury caused by magnetic torque[18]. In our two cases (Figures 6 and 7), one case was a wooden foreign body whose CT value changed with time and could be examined by MRI. However, the patient deteriorated rapidly after admission and developed cerebral hernia. MRI was not conducted because of the length of time it would have required, during which the patient might have experienced adverse events. Intracranial vascular injury in all PBI cases accounts for 20% to 30%, and this complication can be life-threatening[19]. There are three main types of performance: arterial dissection, subarachnoid haemorrhage, and traumatic intracranial aneurysms[19]. Therefore, angiography is strongly recommended when vascular damage is suspected.

Regarding the selection of surgical timing, extremely early foreign body removal may cause massive bleeding due to the change in the pressure gradient, while delayed operation brings an increased risk of infection[20]. The current recommendation is that surgery is performed within 12 h[9,20]. The surgical approaches are divided into a transorbital approach and a transcranial approach. Theoretically, there is a risk of rapid bleeding and death when removing a foreign body from a damaged blood vessel through a transorbital approach in the absence of proper preoperative preparation to prevent or avoid bleeding[8]. The transcranial approach leaves less residual foreign body and provides easier control in cases complicated with great vascular injury. Therefore, the two cases reported here were treated by transcranial surgery. No foreign body remained in the postoperative CT examination. Therefore, the transcranial approach should be the first choice for this type of surgery.

In addition to intracranial hematoma and nerve injury, infection is also a common complication of orbital PBI. In terms of the patient benefit index, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be used as early as possible[9]. A large-scale, retrospective, civilian PBI report showed that the incidence of infection was 1%-5% under broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment[19]. With the continuous abuse of antibiotics and the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria, appropriate antibiotics is recommended for postoperative intervention.

Transorbital PBI is a rare and acute disease. Early diagnosis, surgical intervention, and application of intravenous antibiotics can improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Llompart-Pou JA S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Ramdasi R, Mahore A. Bamboo in the Brain-an Unusual Mode of Injury. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:43-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Estebanez G, Garavito D, López L, Ortiz JC, Rubiano AM. Penetrating Orbital-Cranial Injuries Management in a Limited Resource Hospital in Latin America. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2015;8:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chattopadhyay S, Sukul B, Das SK. Fatal transorbital head injury by bicycle brake handle. J Forensic Leg Med. 2009;16:352-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Farhadi MR, Becker M, Stippich C, Unterberg AW, Kiening KL. Transorbital penetrating head injury by a toilet brush handle. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009;151:685-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shin TH, Kim JH, Kwak KW, Kim SH. Transorbital penetrating intracranial injury by a chopstick. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;52:414-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Arslan M, Eseoğlu M, Güdü BO, Demir I. Transorbital orbitocranial penetrating injury caused by a metal bar. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3:178-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ijaz L, Nadeem MM. Transorbital penetrating brain injury to frontal lobe by a wheel spoke. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2014;9:267-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lefebvre DR, Chandra RV. Diagnosis and treatment of penetrating orbital cranial foreign body injuries. Digit J Ophthalmol. 2012;18:9-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang D, Chen J, Han K, Yu M, Hou L. Management of Penetrating Skull Base Injury: A Single Institutional Experience and Review of the Literature. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2838167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim MS, Sim SY. Traumatic aneurysm of the callosomarginal artery-cortical artery junction from penetrating injury by scissors. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014;55:222-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Skoch J, Ansay TL, Lemole GM. Injury to the Temporal Lobe via Medial Transorbital Entry of a Toothbrush. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2013;74:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nishio Y, Hayashi N, Hamada H, Hirashima Y, Endo S. A case of delayed brain abscess due to a retained intracranial wooden foreign body: a case report and review of the last 20 years. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2004;146:847-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Su YM, Changchien CH. Self-inflicted, trans-optic canal, intracranial penetrating injury with a ballpoint pen. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Yamashita T, Mikami T, Baba T, Minamida Y, Sugino T, Koyanagi I, Nonaka T, Houkin K. Transorbital intracranial penetrating injury from impaling on an earpick. J Neuroophthalmol. 2007;27:48-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sweeney JM, Lebovitz JJ, Eller JL, Coppens JR, Bucholz RD, Abdulrauf SI. Management of nonmissile penetrating brain injuries: a description of three cases and review of the literature. Skull Base Rep. 2011;1:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pomerantz SR, Kamalian S, Zhang D, Gupta R, Rapalino O, Sahani DV, Lev MH. Virtual monochromatic reconstruction of dual-energy unenhanced head CT at 65-75 keV maximizes image quality compared with conventional polychromatic CT. Radiology. 2013;266:318-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yu L, Primak AN, Liu X, McCollough CH. Image quality optimization and evaluation of linearly mixed images in dual-source, dual-energy CT. Med Phys. 2009;36:1019-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mandat TS, Honey CR, Peters DA, Sharma BR. Artistic assault: an unusual penetrating head injury reported as a trivial facial trauma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147:331-3; discussion 332-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Temple N, Donald C, Skora A, Reed W. Neuroimaging in adult penetrating brain injury: a guide for radiographers. J Med Radiat Sci. 2015;62:122-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Caporlingua A, Caporlingua F, Lenzi J. Good outcome after delayed surgery for orbitocranial non-missile penetrating brain injury. Asian J Neurosurg. 2016;11:309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |