Published online Jan 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i2.444

Peer-review started: November 5, 2019

First decision: December 4, 2019

Revised: December 10, 2019

Accepted: January 2, 2020

Article in press: January 2, 2020

Published online: January 26, 2020

Processing time: 72 Days and 13.5 Hours

In clinical practice, checkrein deformity is usually found in patients with calf injuries after ankle fracture or distal tibial fracture. The patients with checkrein deformity mainly report distending pain in toe tips, pain when walking or wearing shoes, and gait instability. Previous studies have mainly reported surgical treatments for checkrein deformity, while few studies have reported using comprehensive rehabilitation alone to improve the checkrein deformity.

A 28-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital due to unstable gait caused by pain in the right hallux, for which she was unable to stretch for over three months. The patient had undergone “resection of ameloblastoma at the right mandible, mandibulectomy, and autogenous right fibula grafting”. The patient’s hallux toe, as well as the second and third toes of the right foot could not be stretched, with pain in all the toes during walking. Based on the medical records of the patient, as well as the results of physical and auxiliary examinations, the main diagnosis was checkrein deformity in the right foot. Since the patient refused surgical treatment, rehabilitation was the only treatment option. At discharge, the patient reported evident improvement in the pain in the toes, gait stability, as well as increased ability to climb up and downstairs.

Comprehensive rehabilitation therapy could effectively alleviate the manifestations of checkrein deformity and improve the walking ability of the patients.

Core tip: We report a rare case of checkrein deformity following fibula osteotomy. The checkrein deformity in this patient could be induced by the injuries to the muscle belly of the flexor halluces longus, and formation of hematoma. For therapy, we used comprehensive rehabilitation treatment such as thermal therapy, medium-high frequency electrotherapy, shock wave therapy, massage, etc. After 20 d of treatment, the pain and gait of the patient had improved. In addition, no relapse of the toe pain was reported during the follow-up after discharge. The daily walking of the patient was not affected. This case indicates that comprehensive rehabilitation can be effectively used in the conservative and postoperative treatment of checkrein deformity.

- Citation: Feng XJ, Jiang Y, Wu JX, Zhou Y. Efficacy of comprehensive rehabilitation therapy for checkrein deformity: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(2): 444-450

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i2/444.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i2.444

Checkrein deformity[1] refers to the rein-like change of the tendon of the flexor hallucis longus, which occurs after lower calf injuries. The hallux toe is forced to extremely flex during dorsal stretch of the ankle joint, but can completely stretch during plantar flexion of the ankle joint, which is also known as movable flexion deformity. This is different from the fixed claw toe deformity caused by lesions in the feet or interphalangeal joint and surrounding tissues. In clinical practice, checkrein deformity is mainly observed after ankle fracture or distal tibial fracture. Some cases of checkrein deformity after intramedullary nail fixation for tibial fracture, long-term burying after earthquake without evident osteofascial compartment syndrome, and very lengthy urological surgery in lithotomy position have also been reported[2-4]. However, checkrein deformity following fibula osteotomy has not been reported to date. Previous studies[5,6] have mainly reported surgical treatments for checkrein deformity, including lengthening of the tendon of flexor hallucis longus, tenolysis, and myotenotomy of the tendon of flexor hallucis longus, followed by rehabilitation to maintain the range of motion of the ankle and toe joints. Few studies have reported using comprehensive rehabilitation alone to improve the checkrein deformity.

Herein, we report a rare case of checkrein deformity following fibula osteotomy. The patient’s toe pain improved evidently and her daily walking ability increased after rehabilitation therapy. Our experience in treating this case could be of guiding value for clinical practice.

A 28-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to unstable gait caused by pain in the right hallux, for which she was unable to stretch for over three months.

The patient had undergone “resection of ameloblastoma at the right mandible, mandibulectomy, and autogenous right fibula grafting” at another hospital on November 20, 2017. The right lower limb of the patient was wrapped with gauze and fixed with a splint for over 20 d. The patient reported within 20 d that the wrapping was too tight, without any evident pain. The patient started walking with the assistance of a single crutch after the splint was removed, and could walk unaided one month after the operation. However, the hallux toe, as well as the second and third toes of the right foot could not be stretched, with pain in all the toes. Therefore, the gait of the patient was unstable, and she was susceptible to fall. Going up and downstairs was very difficult for her.

The patient had no significant medical history, psychiatric history, or history of substance abuse. On admission, the physical examination showed that the patient had clear consciousness, and her mental status was normal.

A healed scar of approximately 15 cm in length was found at the jaw. Another healed scar of approximately 28 cm in length was found at the posterolateral side of the right calf. No evident swelling was found in the right calf and right foot, and no evident pressing pain was found around the right ankle. The motion of the right ankle was restricted, and the parameters were as follows: Dorsal flexion was about 0°; plantar flexion was about 45°, which was generally normal; the right hallux toe was slightly valgus; the second and third toe joints were flexed and could not be stretched when the ankle joint was in neutral position. However, these two toe joints could be stretched during plantar flexion of the ankle. The circumference of the calf was 21.5 cm and 22.5 cm at 10 cm above the right and left ankles, respectively. In addition, the circumference of the calf was 29.5 cm and 31.5 cm at 20 cm above the right and left ankles, respectively. Hypoesthesia of the skin was found at the lateral side of the right calf and right foot-back. Fluctuation of the dorsal artery was normal (Figure 1).

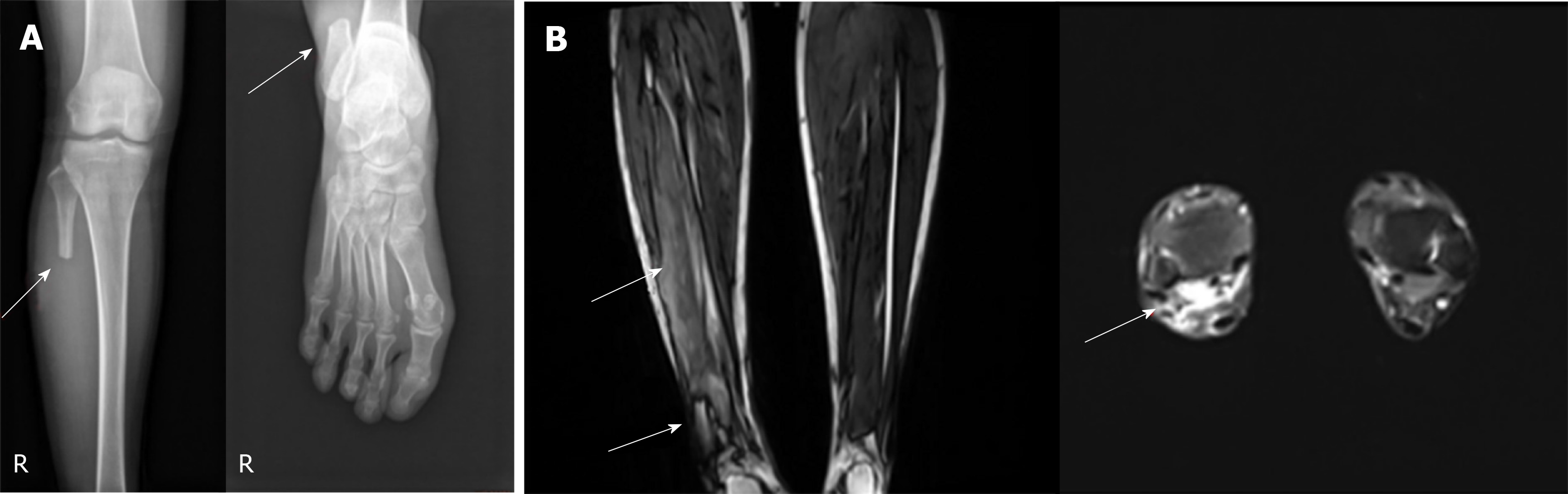

X-ray of the right ankle and right knee performed on March 30, 2018 (Figure 2A) showed discontinuity of the proximal and distal ends of the right fibula, which could be the changes following fibula osteotomy. Electromyography (EMG) performed on April 1, 2018 showed damages of the sural sensory nerves. Color ultrasound examination suggested the possibility of flexor hallucis longus injuries. Magnetic resonance imaging of the right calf on April 12, 2018 (Figure 2B) showed discontinuity of the bony substance of the right fibula, which was postoperative change; abnormal signal of the right flexor hallucis longus that suggested injuries; and tenosynovitis of the right flexor hallucis longus.

Based on the medical records of the patient, as well as the results of physical and auxiliary examinations, the diagnoses were as follows: (1) Acquired deformity in the right foot (checkrein deformity); (2) Stiffness of the right ankle; (3) Disease of the right fibula (post-fibula osteotomy); (4) Synovitis of the right ankle joint; and (5) Tenosynovitis of the right flexor hallucis longus.

The patient refused surgical treatment. Therefore, rehabilitation plan was developed after comprehensive rehabilitation assessment. The course of the comprehensive rehabilitation therapy was 20 d, which included the following treatments: Shock wave therapy, interferential therapy, and paraffin therapy of the right calf; massage therapy of the right calf and right ankle; traditional Chinese medicine fumigation and ultrashort wave therapy of the right ankle; mobilization of the right ankle joint and toe joints, and manual stretching of the tendons; and motor therapy of the right lower limb.

At discharge, the patient reported evident improvement in the pain in the toes, gait stability, as well as increased ability to climb up and downstairs. Physical examination showed that the dorsal flexion of the ankle was about 5°, plantar flexion was generally normal, but the hallux toe, as well as the second and third toe joints could not be positively stretched up the dorsal stretch of the ankle.

The treatment efficacy was assessed by the visual analogue scale (VAS) and gait analysis on admission, at discharge, and at three and six months after discharge.

A 10-cm-long line was drawn on a piece of paper. The left end of the line was marked as 0, which indicated no pain; the right end of the line was marked as 10, which indicated drastic pain; while the middle portion indicated pain of different degrees. The patient was asked to mark the line at the corresponding position to indicate the pain she suffered. The results are shown in Table 1.

| Admission | Discharge | 3 mo after discharge | 6 mo after discharge | |

| VAS score | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Gait analysis was conducted in an environment with sufficient sunshine at room temperature (23 °C), using a digital running table (Tecno Body Walker-view). The patient was guided for a 2-min accelerated walk on the table before each test. After the walking speed was increased to 3.4 km/h, the treadmill was set at a fixed speed of 3.4 km/h. The gait-associated data of the patient was dynamically recorded during the walk at a fixed speed. The processes were repeated twice, and the average of the three measurements was calculated. The mean floor-touching time of both feet and mean dorsal flexion angle of the ankle when touching the floor in each gait cycle within the 2 min were selected as the parameters for the gait analysis. The results are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Floor-touching time (s) | Admission | Discharge | 3 mo after discharge | 6 mo after discharge |

| Left foot | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.64 |

| Right foot | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.65 |

| Ankle joint (°) | Admission | Discharge | 3 mo after discharge | 6 mo after discharge |

| Left foot | 14.61 | 13.73 | 14.36 | 13.02 |

| Right foot | 0.42 | 5.32 | 4.74 | 6.17 |

The assessment showed the following results: (1) The patient had evident pain before the treatment. However, the ankle pain alleviated after the treatment, and no pain was reported at six months after discharge; (2) The floor-touching time of the right foot was shorter than the left foot before the treatment. However, the floor-touching time of the right foot had increased at discharge, and was generally stabilized at three and six months after discharge; and (3) Before admission, dorsal flexion of the right ankle could not be achieved when the right foot touched the floor. However, the angle of dorsal flexion increased on admission, but remained lower than the left foot. The dorsal flexion angle of the right ankle did not change evidently at three and six months after discharge.

Checkrein deformity was first reported by Jahss[7], and mainly manifests as movement flexion deformity. It is caused by the reduced effective relaxation and contraction lengths of the flexor hallucis longus, which restricts the full-range of motion of the hallux toe. The etiologies and pathogeneses of checkrein deformity remain unclear. Checkrein deformity was suggested to be caused by tendon fixation[1], which refers to the adhesion of the flexor hallucis longus at the osteotylus of fracture. Thus, a bowstring-shaped tendon is formed between this site and the end point of the hallux toe. Therefore, the hallux toe is extremely flexed after dorsal flexion of the ankle joint, but cannot be completely stretched after plantar flexion of the ankle joint. Checkrein deformity was also suggested to be caused by the contracture of corresponding muscle fibers induced by muscle damages and ischemia following osteofascial compartment damages at the deep posterior calf[8].

Herein, we report the first case of checkrein deformity following fibula osteotomy. In clinical practice, it is relatively common to use free fibula flap for repairing bone defects of the limbs. In addition, the free fibula flap is widely used for repairing the mandible. However, these surgeries mainly focus on repairing the bone defects, while the complications following fibula osteotomy are generally neglected. In light of the pathogenesis of checkrein deformity, as well as the results of imaging examinations, ultrasound examinations, and EMG, we speculated that the induction of checkrein deformity post-surgery in this patient could be due to the following two reasons: (1) The lateral flexor hallucis longus originates from the intermuscular septum of the medial peroneal muscle, while the medial flexor hallucis longus originates from the fascia at the surface of posterior tibial muscle. The tendon of flexor halluces longus is located at about 1.5 cm from the proximal tibiotalar joint[9]. During the surgery, the fibula was obtained through the lateral fibula approach, after which the incision was sutured in this patient. However, muscle belly injuries or local hematoma may have occurred during the surgery, which in turn induced extensive scar adhesion; (2) The flexor halluces longus is located at the deepest site of the calf muscles. The fibular side of the deep compartment is wrapped by fascia, and the muscle belly is relatively large, with a bi-pinnate shape[9]. The intra-pressure in the compartment increased due to excessive bleeding during the operation, which in turn induced ischemia and necrosis, while fibrosis of the flexor halluces longus could not be ruled out in the patient; and (3) The patient had reported that the wrapping and splint were too tight, and this could also induce ischemia and contracture of the flexor halluces longus in long term. Therefore, we speculated that the checkrein deformity in this patient could be induced by the injuries to the muscle belly of the flexor halluces longus and formation of hematoma, which induced large areas of scar adhesion in the muscle belly and increased intra-pressure in the compartment, consequently leading to ischemia and contracture of the muscle, and eventually necrosis and fibrosis.

After the patient was admitted to our department, we speculated that large areas of the muscle belly of the flexor halluces longus were injured, adhesive, or had contracture, necrosis, and fibrosis. In addition, the ductility of the tendon was poor, with no positive flexion ability. Stretching the tendon would worsen the tendinitis, and therefore increase the pain, and further increase the difficulty in walking. Therefore, we used thermal therapy to increase the blood circulation in the patient’s calf and ankle to improve the tissue nutrition, and promote the resolution of inflammation. Additionally, medium-high frequency electrotherapy was used to promote the blood circulation, and facilitate analgesia and anti-inflammation. Shock wave therapy and massage were used to soften and lyse the scar, and improve the muscle adhesion. Furthermore, motor therapy of the lower limb, joint mobilization, and passive tendon stretching were used after sufficient lysing of the muscle belly of the flexor halluces longus in order to maintain the range of motion of the ankle and toe joints.

Limited improvement in the toe deformity and range of motion of the ankle joint was achieved after the 20-d treatment, although the toe could not be positively stretched completely, and the dorsal flexion of the ankle remained insufficient during walking. Therefore, we speculated that the bleeding, necrosis, and fibrosis of the muscle belly of the flexor halluces longus could be irreversible in this patient. The effectiveness of the comprehensive rehabilitation in lysing the muscle belly of the flexor halluces longus was limited, and surgical treatment could be conducted if necessary.

However, the VAS score of the patient decreased, the floor-touching time increased, and the dorsal flexion angle of the ankle joint improved, suggesting that the pain and gait of the patient had improved after the comprehensive rehabilitation therapy. In addition, no relapse of the toe pain was reported during the follow-up at three and six months after discharge. The daily walking of the patient was not affected. These findings demonstrated that the comprehensive rehabilitation therapy is efficacious for pain and altered daily walking ability induced by checkrein deformity. The comprehensive rehabilitation therapy, which is a clinical empirical therapy, was used on this patient, while specific indicators reflecting the efficacy of each treatment were lacking. Further studies are needed to obtain more clinical evidence for the treatment of this disease.

The treatment of checkrein deformity is not restricted to surgery. The treatment efficacy of clinical rehabilitation showed that the therapy not only effectively alleviated the pain but also improved the walking ability of the patient. These findings demonstrated that rehabilitation therapy has important value in conservative and postoperative therapy of checkrein deformity.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Anand A, Papachristou G, Malik H S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Lu SB. Campbell orthopedic surgery. 9th ed. Jinan: Shandong Science and Technology Press, 2001: 2047. |

| 2. | Tischenko GJ, Goodman SB. Compartment syndrome after intramedullary nailing of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:41-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Khan HA, Khan MA, Hassan N. Short Term Results with Z Plasty for Checkrein Deformity Following Tibia Fractures. Indian J Orthopaedics. 2016;2:207-208. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yao XK, Wang Y, Lu B, Zhang B, Wu XJ, Zhao ZE, Li DD, Gu ZR. Comprehensive rehabilitation treatment of thumb flexion deformity with extrusion and disability. Shiyong Guke Zazhi. 2011;17:375-377. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Zhu DB, Yang GT. Etiology and surgical method of checkrein deformity. Hainan Yixue. 2017;28:309-311. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Liu JH, Xu XY. Treatment of flexion deformity of thumb after fibular fracture. Zhonghua Guke Zazhi. 2006;26:594-597. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Jahss MH. Disorders of the foot and ankle. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders WB, 1992. |

| 8. | Feeney MS, Williams RL, Stephens MM. Selective lengthening of the proximal flexor tendon in the management of acquired claw toes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:335-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jiang WX. A report of 2 cases of checkrein deformity of the toenail. Zhongguo Jiaoxing Waike Zazhi. 2006;17:1359-1361. |