Published online Aug 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i15.3341

Peer-review started: March 18, 2020

First decision: June 15, 2020

Revised: June 28, 2020

Accepted: July 15, 2020

Article in press: July 15, 2020

Published online: August 6, 2020

Processing time: 140 Days and 18.6 Hours

Suppurative oesophagitis is a diffuse inflammation of the oesophagus characterized by suppurative exudate or pus formation. Suppurative infections can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly the stomach, with inflammation involving the entire gastric cavity. However, cases extending beyond the cardia or pylorus and involving the oesophagus, small intestine, and colon are rare. Usually such cases are discovered during surgery or autopsy.

We report a rare case of acute suppurative oesophagitis. A 57-year-old man presented at the Emergency Department of our hospital with fever and productive cough. The patient had a significant history of lower oesophageal mucosal frostbite. He was successfully diagnosed and treated with repeated gastroscopy, appropriate antibiotics, and innovative symptomatic treatment.

Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of acute suppurative oesophagitis are critical. Nutritional support, postural drainage, and other symptomatic treatments must be considered.

Core tip: This case report details a particularly interesting and rare case of acute suppurative oesophagitis that developed secondary to suspected mucosal frostbite in the oesophagus. A 57-year-old man, with a significant history of lower oesophageal mucosal frostbite, presented with fever and productive cough. He was successfully diagnosed and treated with repeated gastroscopy, appropriate antibiotics, and innovative symptomatic treatment. We believe that our study makes a significant contribution to the literature as, to our knowledge, this is the first report of oesophageal frostbite predisposing a patient to acute suppurative oesophagitis.

- Citation: Men CJ, Singh SK, Zhang GL, Wang Y, Liu CW. Acute suppurative oesophagitis with fever and cough: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(15): 3341-3348

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i15/3341.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i15.3341

Suppurative oesophagitis is a diffuse inflammation of the oesophagus characterized by suppurative exudate or pus formation[1]. It may develop as a complication of any condition interrupting the continuity of the oesophageal mucosa and allowing pathogenic bacteria to penetrate the oesophageal wall. Traumatic lesions, produced by infected foreign bodies, are an important cause of suppurative oesophagitis. Suppurative infections can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly the stomach, with inflammation involving the entire gastric cavity. However, cases extending beyond the cardia or pylorus, involving the oesophagus, small intestine, and colon, are rare[1-3]. Usually such cases are discovered during surgery or autopsy. Therefore, the early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of this disease is critical. If the lesion involves the mediastinum and the adjacent organs to form a fistula, conservative medical treatment alone may be ineffective, and surgical fistula repair or oesophagectomy may also be required[1,2]. We report a rare case of acute suppurative oesophagitis in a patient admitted for fever with productive cough and a significant history of lower oesophageal mucosal frostbite, who was successfully diagnosed and treated with repeated gastroscopy, appropriate antibiotics, and innovative symptomatic treatment.

A 57-year-old male Chinese farmer (175 cm, 75 kg and yellow race) presented to the Emergency Department of our hospital with fever up to 39.0°C for 3 d, productive cough with yellowish-white sticky sputum with occasional blood stains, and chest pain in the sternal region.

The patient had no obvious cause of fever 3 d before admission. On presentation, he did not have chills or rigor, abdominal pain, or nausea/vomiting and his bowel and bladder habits were normal.

The patient had a history of good physical health and denied a history of any chronic diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, and diabetes. He had no history of major surgery or severe trauma.

He had a history of drinking alcohol socially for more than 30 years. He was a non-smoker and denied a history of drugs and known food allergies.

On admission, his general condition was normal, and his vital signs were stable. A physical examination revealed bilateral breath sounds present with wheeze and crackles. An abdominal examination was unremarkable with normal bowel sounds and a soft, flat abdomen with no general or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory tests revealed the following: White blood cells (WBC): 5.54 × 109/L, neutrophils (N): 78.4%, platelets (PLT): 27 × 109/L; Glucose (GLU): 17.74 mmol/L; Alanine transaminase (ALT): 90 IU/L, aspartate transaminase (AST): 91 IU/L and total bilirubin (TBIL): 117.9 µmol/L. Other routine tests, such as renal function tests and clotting time, did not reveal any abnormalities.

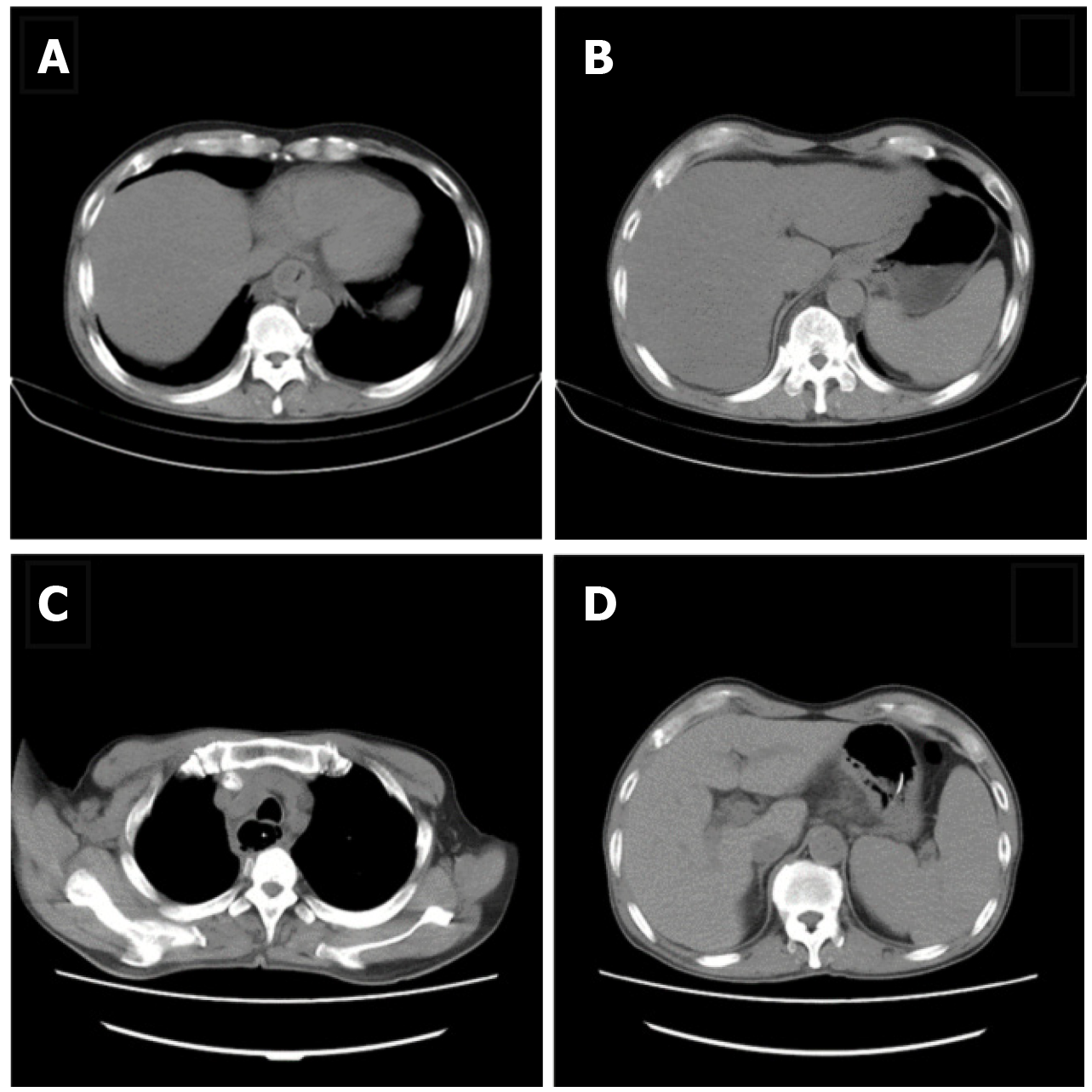

A thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan showed oesophageal dilatation and effusion, wall thickening of the lower oesophagus, inflammation of the upper lobe of the right lung, and bilateral pleural effusion; Abdominal CT scan showed thickening of the gastric wall of the cardia and adjacent lesser curvature of the stomach, fatty liver, and gallstones (Figure 1A and B).

Following antibiotic therapy using piperacillin and sulbactam, the patient still had fever, and the platelet count progressively decreased; thus, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) of our hospital for further diagnosis and treatment. After ICU admission, the relevant tests performed revealed the following: Haemoglobin (HB): 103.00 g/L↓; PLT: 8.00 × 109/L; N: 85.90%↑; (CA): 1.70 mmol/L↓; Albumin (ALB): 26.90 g/L↓; AST: 75.10 U/L↑; GLU: 13.98 mmol/L↑; Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT): 467.00 U/L↑; Triglycerides (TG): 5.40 mmol/L↑; TBIL: 68.30 µmol/L; High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP): 331.300 mg/L↑; Prothrombin time (PT): 15.80 s↑; Plasma thromboplastin antecedent (PTA): 59%↓; D-dimer: 2171.59 µg/L↑; Procalcitonin (PCT): 24.12 ng/mL↑; Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C): 7.1%↑; Tumour markers, hepatitis markers, autoimmune antibodies and viral genome (-); and Blood culture indicated Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The patient received nil per oral and continued on antibiotic therapy with piperacillin sodium and tazobactam, platelet transfusion, hypoproteinaemia correction, ambroxol to break down phlegm, airway strengthening care such as nebulization, expectoration, sputum suction, and acid suppression to protect the gastric mucosa. Maintenance of adequate liver function and water, electrolyte, and acid-base balance was ensured. Intravenous nutrition and other symptomatic and supportive treatments were administered, and when the vital signs stabilized, the patient was transferred to the Department of Gastroenterology for further treatment.

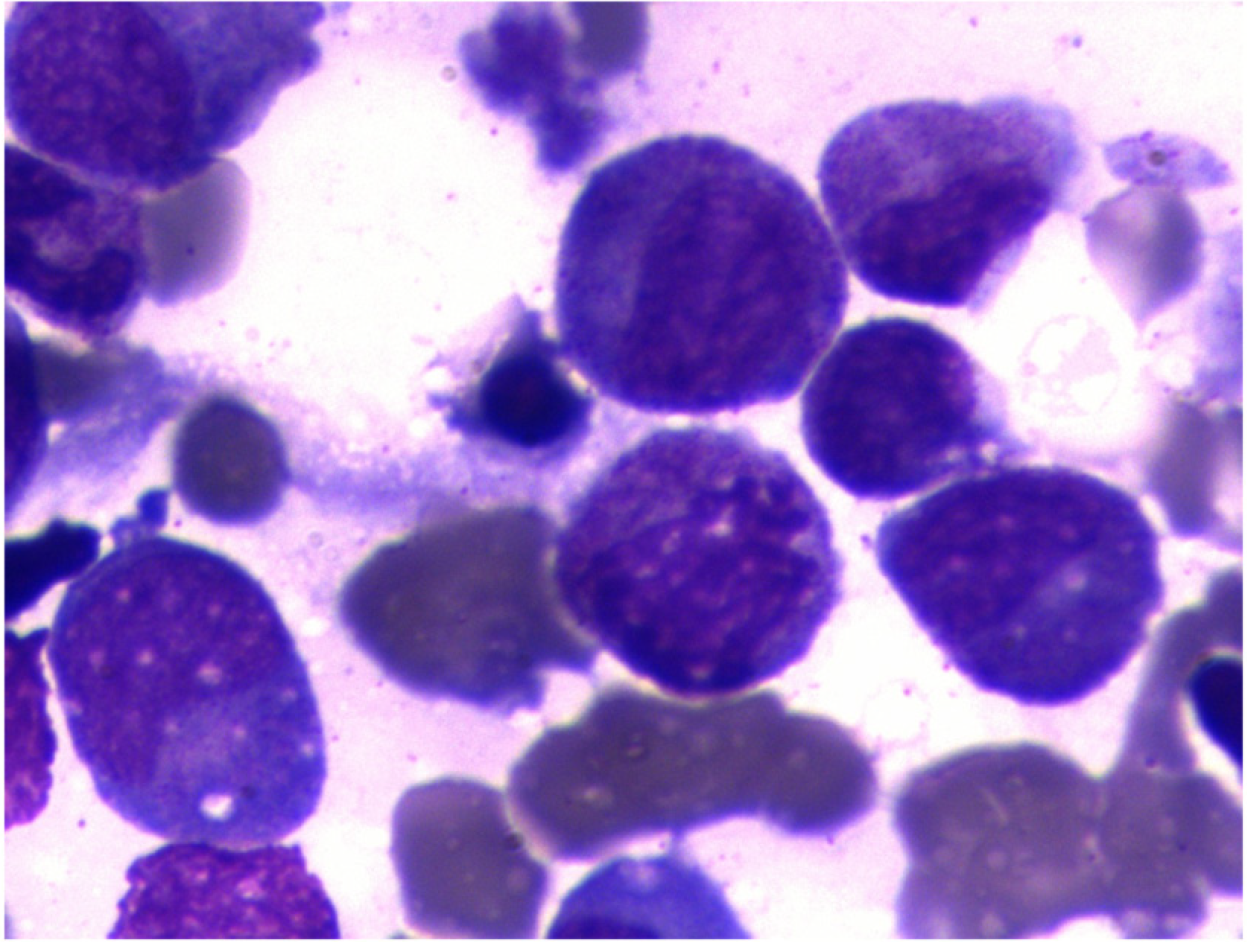

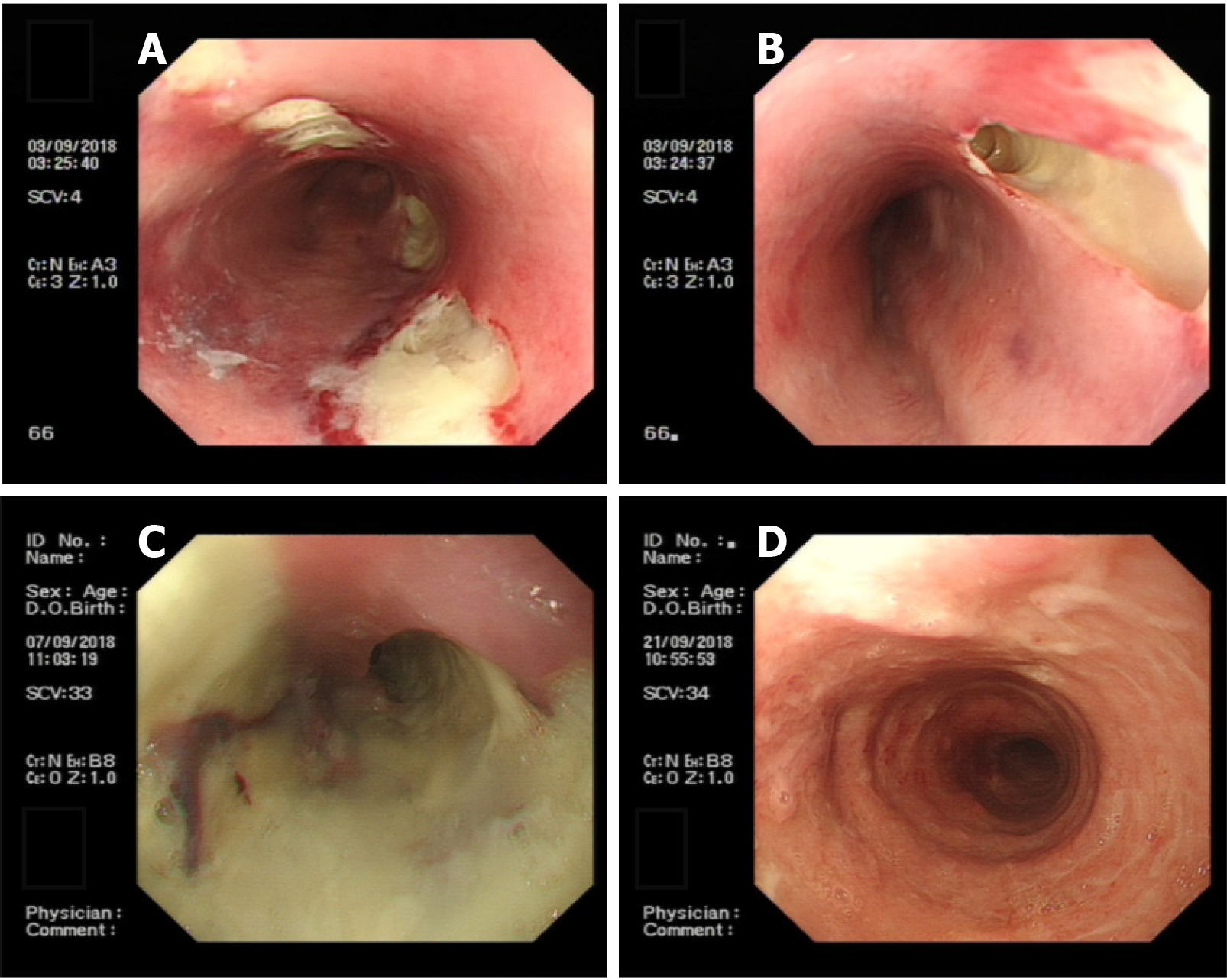

After transfer and active anti-inflammatory treatment, the patient's body temperature gradually normalised, and the PLT count increased to 76 × 109/L, HB: 98.00 g/L↓, N: 82.80%↑, ALB: 28.7 g/L↓, AST: 46.1 U/L↑, TBIL: 34.40 µmol/L↑. Bone marrow aspiration biopsy indicated erythroid hyperplasia due to thrombocytopenia (Figure 2). On the fourth day after admission, gastroscopy showed that there were 4 deep ulcers in the oesophagus 30 cm from the incisor teeth which appeared to be fistulae. The mucosa and sub-mucosa in these regions were completely destroyed, ranging in size from 0.5 cm to 3 cm × 1 cm to 3 cm, and the surface was covered with necrotic tissue and pus (Figure 3A and B). Two deep ulcers were seen on the lesser curvature of the stomach. The diagnosis was considered to be multiple ulcerative changes in the oesophagus and lesser curvature of the stomach with possible fistulae. The next day, upper gastrointestinal tract angiography showed that there was contrast agent oozing out of the lower oesophagus, this was considered to be due to sub-mucosal destruction, and not fistula formation.

On further inquiry, we found that the patient had consciously drunk a large amount of ice water containing hail (irregular shaped ice) a few days before admission. The hail he swallowed may have been retained in the oesophagus, which could have caused local mucosal frostbite of the oesophagus, leading to suppurative infection. In addition, the patient had undergone a Chinese traditional medicine physiotherapy treatment procedure to relieve back pain a few weeks before admission which involved electrodes placed on the sternum and thoracic vertebrae through which current was passed and which could have caused an electro-thermal burn due to the current loop through the upper gastrointestinal tract.

Therefore, the diagnosis was considered to be acute suppurative oesophagitis extending to the lesser curvature of the stomach, causing severe infection leading to thrombocytopenia and hepatic impairment.

Treatment was continued mainly to inhibit gastric acid secretion, to ensure mucosal protection, provide nutritional support, and enhance immunity. On the eighth day after admission, gastroscopy showed that the 4 deep ulcers had merged with each other at 30 cm from the incisor teeth and necrotic substances and pus covered the entire circumference of the oesophagus (Figure 3C). Gastric pus was collected for culture, and biopsy forceps were used to guide the indwelling nasogastric tube. Considering the decrease in haemoglobin and albumin levels and the aggravation of malnutrition symptoms, nasogastric tube feeding of enteral nutrition preparations was performed to strengthen nutritional support and oral feeding was forbidden to protect the oesophageal mucosa. According to the bacterial drug sensitivity results, a levofloxacin injection was administered, and the mucosal protective agent dosage, and the frequency of special insulin injections were increased to control blood glucose.

During the treatment period, the results of tuberculosis-related tests were as follows: Adenosine deaminase (ADA) (-); T-spot test (±); and Purified protein derivative (PPD) (-). The Department of Infectious Disease consulted on the case to rule out tuberculosis. Gram-positive cocci and negative bacilli were found in the pus smears, but no acid-fast bacilli were found. On the fourteenth day after admission, gastroscopy showed oesophageal circumferential ulceration at 28-32 cm from the incisors and the mucosa was completely disrupted and exfoliated; the lesser curvature of the stomach showed a flaky ulcer approximately 2–3 cm in size. Pus on the surface of the ulcer was retained for culture. Normal saline (1000 mL) with levofloxacin injection (250 mL) was used to repeatedly wash the ulcer site. New granulation tissue was seen at the bottom of the ulcer and the bottom surface of the ulcer was cleaned thoroughly before a biopsy was taken and sent for pathological examination. Normal saline was used for haemostasis. The nasogastric tube was retained through the guide wire again. Pathological examination results showed chronic inflammation of the oesophageal squamous epithelial mucosa with erosion and inflammatory granulation tissue hyperplasia, no caseous granuloma, and interstitial infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Immunohistochemistry revealed CD3 and CD8 positivity; scattered CD20 positivity; cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) negativity; and a Ki-67 index of 30%. On the day of gastroscopy, the patient's body temperature was elevated to 38.7°C. Chest CT scan re-examination revealed oesophageal mucosal exfoliation involving the stomach wall. Right upper and middle lobe inflammation had improved since the previous report and oesophageal dilatation and effusion had reduced (Figure 1C and D). Antibiotic treatment with piperacillin sodium and tazobactam was continued in addition to nasogastric tube feeding of enteral nutrition preparation, fluid therapy, and monitoring of inflammatory indicators. As the patient’s body temperature continued to elevate above 38.5°C, we reviewed the laboratory investigations which showed no abnormalities in routine bloods, WBC, and N. Fungus 1-3-β-D glucan < 60 pg/mL, galactomannan < 0.1 µg/L, and other fungal infection test results were normal. Pathogenic bacteria were not observed following pus cultivation. Considering that the laboratory investigations and the consultation with the Department of Infectious Disease had not revealed abnormalities and that the patient's gastroscopy review reports showed improvement, we concluded that the persistent fever was caused by piperacillin sodium and tazobactam and these drugs were discontinued. The patient's body temperature gradually normalised after the drugs were discontinued. After that, the patient was allowed a small amount of oral food intake; conscious eating, swallowing without choking and burning sensation, were significantly better than before. Due to financial reasons, the patient was transferred back to his hometown for further treatment. On the 22nd day after admission, the review of gastroscopy performed before discharging the patient revealed visible granulation tissue on the surface of the entire circumference of the oesophageal mucosal lesion 21–38 cm from the incisor teeth (Figure 3D). The patient was discharged with an indwelling nasogastric tube and advised to continue enteral nutrition. The patient was counselled to consider the possibility of complications such as oesophageal stricture, re-ulceration, and infection and advised to regularly review gastroscopy and tuberculosis indicators if necessary.

Suppurative infections can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly the stomach, with inflammation involving the entire gastric cavity, but cases extending beyond the cardia or pylorus involving the oesophagus, small intestine and colon are rare[1,2]. Reports of simultaneous involvement of the oesophagus and stomach are very limited. Inflammation may involve the muscular layer or even the serosal layer, leading to perforation or oesophageal fistula or even peritonitis[1]. In this case, the suppurative inflammation of the patient extended from the oesophagus across the cardia to the lesser curvature of the stomach. The predisposing factors of suppurative oesophagitis include immunosuppression, alcoholism, peptic ulcer, chronic gastritis or other gastric mucosal lesions, gastric juice deficiency, infection, connective tissue diseases, and malignant tumours[2,3]. Physical and chemical factors such as foreign body or mechanical injury, severe vomiting, accidental use of corrosive agents, iatrogenic traumatic injury during gastroscopy, and consuming too much hot food may be involved. In addition to this, the oesophagus is situated adjacent to the respiratory tract where more pathogenic bacteria occur. Thus, damage to the oesophageal mucosal epithelium decreases its barrier function resulting in bacterial proliferation in the oesophageal wall causing local exudation, necrosis, and pus formation in different tissues. Infection can be more limited, manifesting as one or several small abscesses, or can be a more extensive cellulitis, involving the surrounding oesophageal tissue, mediastinum, or adjacent organs to form a fistula, which is life-threatening. Even so, about half of the total number of patients suffering from suppurative oesophagitis present without any significant cause or risk factors[4]. This patient developed symptoms after drinking a large amount of ice water, containing hail, which may have caused local mucosal frostbite of the oesophagus.

Pathological examination revealed sub-mucosal thickening with neutrophils and plasma cell infiltration with suspected necrosis and sub-mucosal vascular thrombosis. The most common pathogens are Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Proteus, and Clostridium[4], with Streptococcus accounting for approximately 70%–75% of cases. The mucosal biopsy pathological results and blood culture results in this patient revealed that the causative organism of the suppurative infection was Klebsiella pneumoniae. The most common symptoms of suppurative infection involving the oesophagus are post-sternal pain, dysphagia, general malaise, and chest pain[1]. However, some patients may only have fever. This is a very rare case where the patient’s symptoms were fever with productive cough and yellowish-white sticky sputum. Gastroscopy can show diffuse oesophageal stenosis and ulcerative lesions. Endoscopic examination in some patients can also indicate the formation of pseudo membrane, which is an important indicator of the severity of injury due to bacterial infection of the oesophagus. A thoracic CT scan showed diffuse thickening of the oesophageal wall. The low-density shadow in the oesophageal wall suggested that the abscess was confined to the sub-mucosal and muscular layers and that there were mixed gas shadows, suggesting that perforation may be present.

The drugs of choice for this disease are antibiotics such as penicillin and cephalosporin. Corroborating the drug of choice through drug sensitivity testing is always advisable to avoid drug resistance and its unnecessary side effects; the rational use of antibiotics is very important. Most abscesses can drain into the oesophageal cavity by themselves, but sometimes needle aspiration of pus or drainage of the abscess is required under gastroscopy. If the lesion involves the mediastinum and the adjacent organs to form a fistula, conservative medical treatment alone may be ineffective and surgical fistula repair or oesophagectomy might be required[1,5]. In addition to the primary treatment measures of elimination of predisposing factors and proper antibiotic selection and application[1,2], attention must be paid to nutritional support, postural drainage, and other symptomatic treatments at the same time. As bacteria can easily and aggressively invade the mucosa following oesophageal mucosa damage, and to avoid re-injury of the mucosa during the eating process due to local friction of food on the oesophageal wall, the patient should be fed via a nasogastric tube. In this case, the patient’s oesophageal mucosa was not timely protected and was further injured by daily food intake via the oral route which led to the expansion of the mucosal ulcer to form an abscess and even a possible fistula. A valuable lesson has been learned from this case. It is suggested that patients should be placed in the semi-recumbent position to prevent the regurgitation of gastric contents and enhance the action of the mucosal protective agent. In this case, oral antibiotic solution and endoscopic mucosal irrigation were used, and the patient was instructed to remain in the supine position following medication administration, which effectively prolonged the retention time of the drugs in the oesophagus and achieved a good therapeutic effect. During the course of treatment, when the condition is recurrent and progressive, the cause should be identified promptly and the exclusion of oesophageal tuberculosis, lymphoma, Crohn's disease and oesophageal cancer should be prioritized. Repeated gastroscopy and mucosal biopsy can be performed to confirm the diagnosis, if the patient's condition permits; however, the spread of infection, bleeding, and perforation must be avoided during the procedures.

For acute suppurative oesophagitis patients with localized lesions, the prognosis is mostly favourable but oesophageal stenosis, recurrent pulmonary infection, oesophageal carcinogenesis, peritonitis, and even death may occur in patients with extensive lesions and an uncontrolled condition. Therefore, as medical personnel, we should pay close attention to collecting a detailed patient history, avoid the abuse or unnecessary use of antibiotics in clinical work, and reduce the incidence of misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis, thereby reducing the physiological and psychological burden on patients and improving the cure rate. Timely and correct diagnosis and treatment will greatly reduce the wastage of medical resources, which will benefit both parties: The patients and the medical fraternity.

The early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of acute suppurative oesophagitis is critical. Along with detailed patient history taking, choice of appropriate antibiotics, and repeated gastroscopy, we must also pay attention to the nutritional support, postural drainage, and other symptomatic treatments to attain optimal results.

We would like to thank the patient for giving consent for publication, and we are grateful to all research staff and co-investigators involved in this case study.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Chinese Medical Association, No. 201310089

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sirin G S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Hsu CY, Liu JS, Chen DF, Shih CC. Acute diffuse phlegmonous esophagogastritis: report of a survived case. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1347-1352. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Karimata H, Nishimaki T, Oshita A, Nagahama M, Shimoji H, Inamine M, Kinjyo T. Acute phlegmonous esophagitis as a rare but threatening complication of chemoradiotherapy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44:1147-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yun CH, Cheng SM, Sheu CI, Huang JK. Acute phlegmonous esophagitis: an unusual case (2005: 8b). Eur Radiol. 2005;15:2380-2381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim GY, Ward J, Henessey B, Peji J, Godell C, Desta H, Arlin S, Tzagournis J, Thomas F. Phlegmonous gastritis: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim JW, Ahn HY, Kim GH, Kim YD, Hoseok, Cho JS. Endoscopic Intraluminal Drainage: An Alternative Treatment for Phlegmonous Esophagitis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;52:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |