Published online Aug 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i15.3230

Peer-review started: January 14, 2020

First decision: April 12, 2020

Revised: April 25, 2020

Accepted: June 29, 2020

Article in press: June 29, 2020

Published online: August 6, 2020

Processing time: 205 Days and 8.3 Hours

Surgical resection is regarded as the only potentially curative treatment option for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines do not recommend palliative surgery unless there is a risk of severe symptoms. However, accumulating evidence has shown that palliative surgery is associated with more favorable outcomes for patients with metastatic CRC.

To investigate the separate role of palliative primary tumor resection for patients with stage IVA (M1a diseases) and stage IVB (M1b diseases) colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRA).

CRA patients diagnosed from 2010 to 2015 with definite M1a and M1b categories according to the 8th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system were selected from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. To minimize potential selection bias, the data were adjusted by propensity score matching (PSM). Baseline characteristics, including gender, year of diagnosis, age, marital status, primary site, surgical information, race, grade, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, were recorded and analyzed. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to explore the separate role of palliative surgery for patients with M1a and M1b diseases.

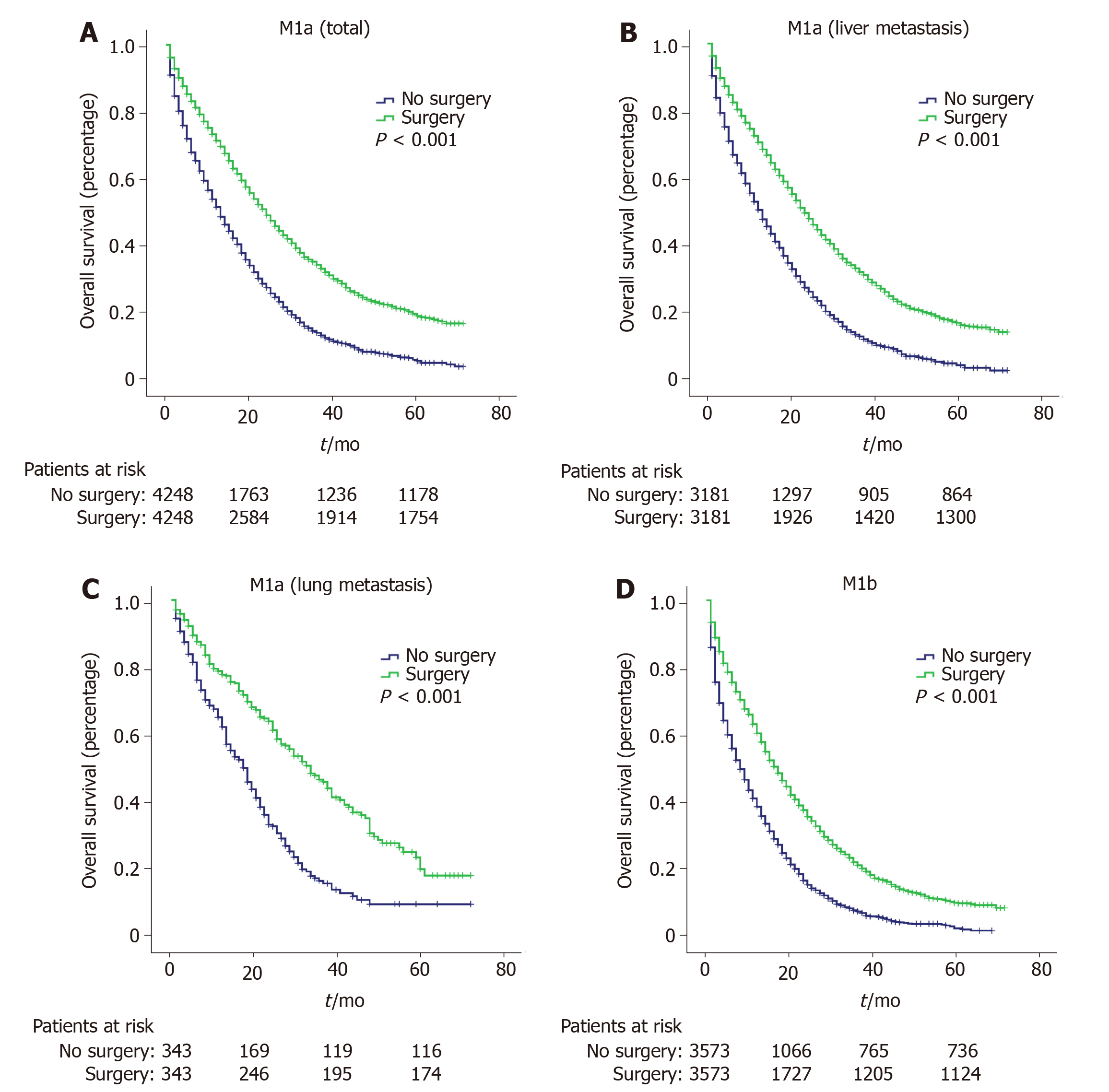

A total of 19680 patients with metastatic CRA were collected from the SEER database, including 10399 cases of M1a diseases and 9281 cases of M1b diseases. Common independent prognostic factors for both M1a and M1b patients included year of diagnosis, age, race, marital status, primary site, grade, surgery, and chemotherapy. After PSM adjustment, 3732 and 3568 matched patients in the M1a and M1b groups were included, respectively. Patients receiving palliative primary tumor resection had longer survival time than those without surgery (P < 0.001). For patients with M1a diseases, palliative resection could increase the median survival time by 9 mo; for patients with M1b diseases, palliative resection could prolong the median survival time by 7 mo. For M1a diseases, patients with lung metastasis had more clinical benefit from palliative resection than those with liver metastasis (15 mo for lung metastasis vs 8 mo for liver metastasis, P < 0.001).

CRA patients with M1a diseases gain more clinical benefits from palliative primary tumor resection than those with M1b diseases. Those patients with M1a (lung metastasis) have superior long-term outcomes after palliative primary tumor resection.

Core tip: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines do not recommend palliative surgery for metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRA). Using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database, we found that patients with M1a diseases had a significant survival benefit compared to those with M1b diseases and patients with M1a (lung metastasis) got best long-term outcomes with median overall survival prolonged by 15 mo compared with those without surgical treatment. These findings provide further evidence to support the use of palliative surgical procedure to treat metastatic CRA and develop effective individualized treatment strategy.

- Citation: Li CL, Tang DR, Ji J, Zang B, Chen C, Zhao JQ. Colorectal adenocarcinoma patients with M1a diseases gain more clinical benefits from palliative primary tumor resection than those with M1b diseases: A propensity score matching analysis. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(15): 3230-3239

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i15/3230.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i15.3230

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the three most common malignancies with 135430 individuals expected to be diagnosed in 2017 in the United States[1]. However, approximately 20% of new CRC patients are diagnosed with distant-stage tumors, resulting in poor long-term outcomes with a 5-year survival rate of 23.2%[2].

Surgical resection is regarded as the only potentially curative treatment option for this disease and could significantly improve the prognosis of patients with metastatic CRC[3]. Rees et al[4] reported that the 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) rate for metastatic CRC patients undergoing primary and hepatic resection was 36%. Abdalla et al[5] showed that patients receiving surgical resection of primary tumors and liver metastases had a 5-year survival rate of up to 58%. Similarly, curative surgical treatment could increase the 5-year survival rate of 32% to 68% in CRC patients with resectable lung metastasis[6,7]. Unfortunately, only one-fifth to one-quarter of metastatic CRC patients can receive curative surgical treatment[8], indicating that metastatic CRC patients are a heterogenous population.

According to the 8th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis staging system, metastatic CRC are classified into M1a (metastasis confined to one organ or site) and M1b (metastases in more than one organ/site or the peritoneum). Complete resection is impossible for most metastatic CRC patients (especially for those with M1b diseases) even after neoadjuvant chemoradiation. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines[9] do not recommend palliative surgery unless there is a risk of significant acute bleeding, obstruction, perforation, or other severe symptoms based on comprehensive analysis of the literature[10-12]. However, accumulating evidence has shown that palliative surgery is associated with more favorable outcomes. For example, a pooled analysis including four randomized trials reported that patients receiving palliative primary tumor removal had prolonged overall survival (OS) compared with those not receiving operation[13]. Another population-based retrospective study reviewing 37793 metastatic CRC patients showed that palliative surgery was significantly related to better OS and CSS[14]. Finally, a systematic review consisting of 21 studies indicated that there was a survival benefit for palliative surgery in patients with metastatic CRC and criteria for palliative surgery should be extended on the basis of World Health Organization (WHO) performance status (PS) or tumor burden[15].

However, to our best knowledge, no studies have classified stage IV into subsets to assess the role of palliative surgery. Adenocarcinoma is the most common pathological type of CRC, accounting for approximately 90% of cases[16]. Thus, we subdivided colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRA) patient populations with stage IV disease on the basis of comorbidities from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database into stage IVA (M1a diseases) and stage IVB (M1b diseases). Outcomes of palliative surgery were then independently assessed.

Patient data, originating between 2010 and 2015, was collected from the SEER database, one of the largest cancer databases in the world[14]. The selection criteria were as follows: (1) Patients 18 years old or older; (2) Disease histologically diagnosed as adenocarcinoma; (3) Treated for first primary tumor; (4) Definite M1a or M1b diseases according to the 8th edition of AJCC staging system; (5) No surgery for metastatic sites (including distant lymph nodes); (6) Surgical procedure or no surgical procedure to primary tumor (excluding tumor destruction or no pathologic specimen or unknown whether there was a pathologic specimen); and (7) Active follow-up. Cases with unknown survival time, status, or those coded as 0 mo were excluded. The entire cohort was divided into two groups based on the median age and calculation result of X-tile program (Yale University, 3.6.1, Supplementary Figure 1). After propensity score matching (PSM), 2935 patients with M1a diseases and 2145 patients with M1b diseases were excluded owing to a lack of counterpart propensity scores. In survival analysis for M1a (liver metastasis) and M1a (lung metastasis), 2202 and 267 patients were further excluded, respectively. Follow-up time ranged from 1 to 71 mo.

Baseline characteristics of metastatic CRA patients, including sex, year of diagnosis, age, marital status, primary site, surgical information, race, grade, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, were recorded and analyzed by χ2 test. The patient prognosis was assessed using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses with hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. To minimize potential selection bias, 1:1 PSM without replacement was used to investigate the effect of palliative primary tumor resection on metastatic CRA. After PSM adjustment, Kaplan-Meier method was employed to analyze the OS for M1a and M1b patients. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A total of 19680 patients with metastatic CRA were collected from the SEER database, which included 10399 cases of M1a diseases and 9281 cases of M1b diseases (Table 1). The entire cohort consisted of 11107 (56.4%) males and 8573 (43.6%) females with a median age of 63 years (ranging from 18 to 108). Most patients were of White ethnicity (74.8%) and more than half of them had well or moderately differentiated tumors (grade I + II). Next, 15476 (78.6%) cases of primary tumors were located in the colon and 4204 (21.4%) in the rectum. The prevalence of metastatic CRA between 2010 and 2012 was similar to that between 2013 and 2015. However, M1b diseases seemed to account for a larger proportion from 48.4% during 2010-2012 to 51.6% during 2013-2015 while M1a diseases showed the opposite prevalence trend.

| Variable | Total (n = 19680) (%) | M1a (n = 10399) (%) | M1b (n = 9281) (%) | P value1 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 8573 (43.6) | 4462 (42.9) | 4111 (44.3) | 0.050 |

| Male | 11107 (56.4) | 5937 (57.1) | 5170 (55.7) | |

| Year of diagnosis | < 0.001 | |||

| 2010-2012 | 9835 (50.0) | 5342 (51.4) | 4493 (48.4) | |

| 2013-2015 | 9845 (50.0) | 5057 (48.6) | 4788 (51.6) | |

| Age (years) | < 0.001 | |||

| < 65 | 10680 (54.3) | 5507 (53.0) | 5173 (55.7) | |

| ≥ 65 | 9000 (45.7) | 4892 (47.0) | 4108 (44.3) | |

| Race | 0.011 | |||

| White | 14715 (74.8) | 7856 (75.5) | 6859 (73.9) | |

| Black | 3033 (15.4) | 1578 (15.2) | 1455 (15.7) | |

| Others | 1932 (9.8) | 965 (9.3) | 967 (10.4) | |

| Marital status | 0.661 | |||

| Married | 9774 (49.7) | 5180 (49.8) | 4594 (49.5) | |

| Others | 9906 (50.3) | 5219 (50.2) | 4687 (50.5) | |

| Primary site | 0.027 | |||

| Colon | 15476 (78.6) | 8114 (78.0) | 7362 (79.3) | |

| Rectum | 4204 (21.4) | 2285 (22.0) | 1919 (20.7) | |

| Grade | < 0.001 | |||

| I + II2 | 11321 (57.5) | 6525 (62.7) | 4796 (51.7) | |

| III + IV3 | 3889 (19.8) | 1909 (18.4) | 1980 (21.3) | |

| Others | 4470 (22.7) | 1965 (18.9) | 2505 (27.0) | |

| Surgery | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 9360 (47.6) | 5787 (55.6) | 3573 (38.5) | |

| No | 10320 (52.4) | 4612 (44.4) | 5708 (61.5) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.415 | |||

| Yes | 14057 (71.4) | 7402 (71.2) | 6655 (71.7) | |

| No/unknown | 5623 (28.6) | 2997 (28.8) | 2626 (28.3) | |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 975 (5.0) | 670 (6.4) | 305 (3.3) | < 0.001 |

| No | 18705 (95.0) | 9729 (93.6) | 8976 (96.7) |

Of the entire cohort, 14057 (71.4%) metastatic CRA patients received chemotherapy and 975 (5.0%) received radiotherapy; 9360 (47.6%) metastatic CRA patients received palliative primary tumor resection while 10320 (52.4%) did not. The proportion of patients with M1a diseases undergoing surgical procedure was much higher than that of M1b diseases (55.6% for M1a and 38.5% for M1b).

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for OS for both M1a and M1b patients were performed (Table 2). The common independent prognostic factors in both M1a and M1b patients included year of diagnosis (2010-2012 vs 2013-2015), age (< 65 vs ≥ 65), race (white vs black), marital status (married vs others), primary site (colon vs rectum), grade (I + II vs III + IV), surgery (yes vs no), and chemotherapy (yes vs no/unknown). Radiotherapy (yes vs no) was an independent prognostic factor for M1a patients but not for M1b patients.

| M1a | M1b | |||||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Male | 1.100 (1.054-1.147) | < 0.001 | 1.025 (0.975-1.077) | 0.339 | 1.043 (1.002-1.086) | 0.042 | 1.020 (0.972-1.070) | 0.428 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||

| 2010-2012 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 2013-2015 | 0.972 (0.929-1.016) | 0.208 | 0.981 (0.929-1.036) | 0.486 | 0.965 (0.925-1.006) | 0.096 | 0.972 (0.924-1.023) | 0.277 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| < 65 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 1.675 (1.606-1.746) | < 0.001 | 1.413 (1.344-1.485) | < 0.001 | 1.527 (1.466-1.589) | < 0.001 | 1.319 (1.256-1.385) | < 0.001 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Black | 1.138 (1.075-1.206) | < 0.001 | 1.114 (1.042-1.192) | 0.002 | 1.127 (1.068-1.191) | < 0.001 | 1.137 (1.064-1.215) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 0.910 (0.844-0.981) | 0.013 | 0.864 (0.792-0.942) | 0.001 | 0.953 (0.891-1.020) | 0.164 | 0.952 (0.878-1.031) | 0.227 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Others | 1.326 (1.272-1.383) | < 0.001 | 1.142 (1.086-1.201) | < 0.001 | 1.212 (1.165-1.262) | < 0.001 | 1.078 (1.026-1.132) | 0.003 |

| Primary site | ||||||||

| Colon | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Rectum | 0.799 (0.758-0.841) | < 0.001 | 0.759 (0.711-0.811) | < 0.001 | 0.839 (0.797-0.882) | < 0.001 | 0.779 (0.731-0.830) | < 0.001 |

| Grade | ||||||||

| I + II | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| III + IV | 1.530 (1.450-1.614) | < 0.001 | 1.580 (1.484-1.682) | < 0.001 | 1.447 (1.375-1.523) | < 0.001 | 1.506 (1.417-1.601) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 1.702 (1.614-1.795) | < 0.001 | 1.149 (1.074-1.228) | < 0.001 | 1.544 (1.473-1.619) | < 0.001 | 1.178 (1.109-1.251) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No | 1.953 (1.859-2.051) | < 0.001 | 2.133 (2.011-2.262) | < 0.001 | 1.632 (1.552-1.716) | < 0.001 | 1.955 (1.843-2.074) | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No/unknown | 2.520 (2.395-2.651) | < 0.001 | 2.282 (2.164-2.405) | < 0.001 | 2.558 (2.430-2.692) | < 0.001 | 2.565 (2.432-2.705) | < 0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No | 2.337 (2.069-2.639) | < 0.001 | 1.236 (1.085-1.408) | 0.001 | 1.695 (1.465-1.961) | < 0.001 | 0.946 (0.813-1.101) | 0.472 |

After PSM adjustment, we obtained 3732 and 3568 matched patients in the M1a and M1b groups, respectively. Their survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method (Figure 1A and D). Patients receiving palliative primary tumor resection had longer survival time than those without surgery (P < 0.001). For patients with M1a diseases, palliative resection could increase the median survival time by 9 mo; for patients with M1b diseases, palliative resection can prolong the median survival time by 7 mo (Table 3). Then M1a diseases were further subdivided by metastatic site. Patients with liver metastasis and lung metastasis were included in the further analysis, whereas patients with bone metastasis and brain metastasis were excluded because of small sample size. As shown in Figure 1B and C, patients with lung metastasis could obtain more clinical benefit from palliative resection than those with liver metastasis (15 mo for lung metastasis vs 8 mo for liver metastasis, Table 3, P < 0.001).

| Median survival time (95%CI) | 1-yr survival rate (%) | 3-yr survival rate (%) | |

| M1a (total) | |||

| No surgery | 14 (13.275-14.725) | 54.4 | 13.9 |

| Surgery | 23 (21.977-24.023) | 70.4 | 32.6 |

| M1a (liver metastasis) | |||

| No surgery | 14 (13.320-14.780) | 53.8 | 13.4 |

| Surgery | 22 (20.955-23.045) | 69.2 | 29.8 |

| M1a (lung metastasis) | |||

| No surgery | 18 (15.692-20.308) | 62.2 | 18.6 |

| Surgery | 33 (28.014-37.986) | 77.5 | 45.4 |

| M1b | |||

| No surgery | 10 (9.401-10.599) | 42.2 | 8.6 |

| Surgery | 17 (16.209-17.791) | 60.0 | 20.4 |

Metastatic CRC is a lethal disease with a poor prognosis. While patients with metastatic CRC can obtain clinical benefits from curative surgery, there is still controversy with respect to the role of palliative primary tumor resection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first population-based study subdividing stage IV into stages IVA (M1a diseases) and IVB (M1b diseases) to evaluate the effect of palliative primary tumor resection. It was determined that patients with M1a diseases could obtain more survival benefits than those with M1b diseases and patients with M1a (lung metastasis) got best long-term outcomes with median OS prolonged by 15 mo compared with those without surgical treatment. These findings provided further evidence to support palliative surgical procedure to metastatic CRA and develop effective individualized treatment strategy.

There were many predictors of OS in patients with unresectable metastatic CRC, including WHO PS, carcinoembryonic antigen level, number of metastatic sites, and palliative surgery[13]. Li et al[17] showed that tumor location (right colon vs left colon vs rectum) was also an independent prognostic factor for metastatic CRC. The results were in line with our findings that patients with rectal cancer were at a lower risk of death than those with colon cancer, possibly owing to higher proportion of lung metastasis in patients with rectal cancer[18]. However, no studies focus on the effect of palliative surgery according to the number of metastatic sites or organs (M1a or M1b). Tarantino et al[14] reported that the survival difference between patients with palliative resection and those without palliative resection was anticipated to decrease due to the development of chemotherapeutic and molecule-targeted drugs. Actually, the significance of survival difference has persisted over time. This may be explained by the heterogeneity of stage IVA (M1a diseases) and stage IVB (M1b diseases). The development of systemic treatment could decrease the survival difference and increase surgery conversion indeed. The proportion of M1b diseases grew from 48.6% during 2010-2012 to 51.6% during 2013-2015 (Table 1, P < 0.001) and such patients were less likely to undergo surgical treatment than those with M1a diseases. This may also explain the decreased rate of patients undergoing primary tumor removal observed during 1998-2009 in Tarantino’s study[14].

Liver and lung metastases are the most two common distant metastases from CRC[7], accounting for 50% and 10%-15% of CRC, respectively[19,20]. The prognosis of patients with liver or lung metastasis is usually better than those with brain or bone metastasis[21]. According to the published literature, median OS was 3-6 mo for patients with brain metastases and 5-7 mo for those with bone metastases[22-28]. For patients with unresectable liver metastases who were treated with chemotherapy only, median OS was approximately 20 mo[29]. By comparison, patients with unresectable lung metastases, who achieved a complete or partial response to chemotherapy, could achieve a median OS of 27 mo[30]. From the perspective of epidemiology, the median time between the diagnosis of CRC and the emergence of liver metastases was shorter than that for lung metastases (17.2 mo for liver vs 24.6 mo for lung)[31], which indicated that liver metastases possessed more aggressive malignant behavior to some extent. These survival findings were similar to the present results (22 mo for liver metastasis with palliative surgery vs 33 mo for lung metastasis with palliative surgery).

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. PSM can adjust potential confounding variables and decrease selection bias as much as possible, increasing precision by creating a ‘quasi-randomized’ experiment[32]. However, we would like to acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, some significant factors such as surgical complications, life quality, operative tolerance, and laboratory parameters were not included. Second, detailed number of metastases in a single organ was not provided in the SEER database, which hampered further analysis for M1a diseases. Third, further classifications for M1 category in the AJCC staging system were not recorded before 2010, and only patient data between 2010 and 2015 were collected. The conclusions should be validated by more prospective data in the future.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines do not recommend palliative surgery for metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRA) unless there is a risk of significant acute bleeding, obstruction, perforation, or another severe symptom.

Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that palliative surgery for metastatic CRA patients was associated with more favorable outcomes. However, no studies further classified CRA patients with stage IV into subsets to assess the role of palliative surgery.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the separate role of palliative primary tumor resection for CRA patients with stage IVA (M1a diseases) and stage IVB (M1b diseases).

CRA patient records with definite M1a and M1b categories were analyzed by adjusted propensity score matching. Patient prognosis was assessed by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses with hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Patients with metastatic CRA receiving palliative primary tumor resection had a longer survival time than those who did not (P < 0.001). Palliative resection increased the median survival time by 9 mo and by 7 mo for patients with M1a and M1b diseases, respectively. For M1a diseases, patients with lung metastasis had more survival benefit from palliative resection than those with liver metastasis (15 mo for lung metastasis vs 8 mo for liver metastasis, P < 0.001).

Palliative primary tumor resection improves survival for all CRA patients but more beneficial for those with M1a diseases than those with M1b diseases. Specifically, patients with M1a (lung metastasis) had the best long-term outcomes after palliative primary tumor resection.

These findings provided further evidence to support the use of palliative surgical procedures to treat metastatic CRA and develop effective individualized treatment strategies.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Akbulut S, Lee CL, Nakano H S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11065] [Cited by in RCA: 12178] [Article Influence: 1522.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Zhang J, Gong Z, Gong Y, Guo W. Development and validation of nomograms for prediction of overall survival and cancer-specific survival of patients with Stage IV colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2019;49:438-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tomasello G, Petrelli F, Ghidini M, Russo A, Passalacqua R, Barni S. FOLFOXIRI Plus Bevacizumab as Conversion Therapy for Patients With Initially Unresectable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:e170278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, O'Rourke T, John TG. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:125-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in RCA: 806] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Ellis V, Pollock R, Broglio KR, Hess K, Curley SA. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818-25; discussion 825-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1364] [Cited by in RCA: 1285] [Article Influence: 61.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Riquet M, Foucault C, Cazes A, Mitry E, Dujon A, Le Pimpec Barthes F, Médioni J, Rougier P. Pulmonary resection for metastases of colorectal adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:375-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vatandoust S, Price TJ, Karapetis CS. Colorectal cancer: Metastases to a single organ. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11767-11776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | de Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Andreani P, Pascal G, Saliba F, Ichai P, Adam R, Castaing D, Azoulay D. Impact of expanding criteria for resectability of colorectal metastases on short- and long-term outcomes after hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 2011;253:1069-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Benson AB, Venook AP, Cederquist L, Chan E, Chen YJ, Cooper HS, Deming D, Engstrom PF, Enzinger PC, Fichera A, Grem JL, Grothey A, Hochster HS, Hoffe S, Hunt S, Kamel A, Kirilcuk N, Krishnamurthi S, Messersmith WA, Mulcahy MF, Murphy JD, Nurkin S, Saltz L, Sharma S, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous CT, Stoffel EM, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Willett CG, Wu CS, Gregory KM, Freedman-Cass D. Colon Cancer, Version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 70.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Benoist S, Pautrat K, Mitry E, Rougier P, Penna C, Nordlinger B. Treatment strategy for patients with colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1155-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Galizia G, Lieto E, Orditura M, Castellano P, Imperatore V, Pinto M, Zamboli A. First-line chemotherapy vs bowel tumor resection plus chemotherapy for patients with unresectable synchronous colorectal hepatic metastases. Arch Surg. 2008;143:352-8; discussion 358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Seo GJ, Park JW, Yoo SB, Kim SY, Choi HS, Chang HJ, Shin A, Jeong SY, Kim DY, Oh JH. Intestinal complications after palliative treatment for asymptomatic patients with unresectable stage IV colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:94-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Faron M, Pignon JP, Malka D, Bourredjem A, Douillard JY, Adenis A, Elias D, Bouché O, Ducreux M. Is primary tumour resection associated with survival improvement in patients with colorectal cancer and unresectable synchronous metastases? A pooled analysis of individual data from four randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:166-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tarantino I, Warschkow R, Worni M, Cerny T, Ulrich A, Schmied BM, Güller U. Prognostic Relevance of Palliative Primary Tumor Removal in 37,793 Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Population-Based, Propensity Score-Adjusted Trend Analysis. Ann Surg. 2015;262:112-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Anwar S, Peter MB, Dent J, Scott NA. Palliative excisional surgery for primary colorectal cancer in patients with incurable metastatic disease. Is there a survival benefit? A systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:920-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li C, Zheng H, Jia H, Huang D, Gu W, Cai S, Zhu J. Prognosis of three histological subtypes of colorectal adenocarcinoma: A retrospective analysis of 8005 Chinese patients. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3411-3419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li Y, Feng Y, Dai W, Li Q, Cai S, Peng J. Prognostic Effect of Tumor Sidedness in Colorectal Cancer: A SEER-Based Analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18:e104-e116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tamas K, Walenkamp AM, de Vries EG, van Vugt MA, Beets-Tan RG, van Etten B, de Groot DJ, Hospers GA. Rectal and colon cancer: Not just a different anatomic site. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:671-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Biasco G, Derenzini E, Grazi G, Ercolani G, Ravaioli M, Pantaleo MA, Brandi G. Treatment of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: many doubts, some certainties. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:214-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mitry E, Guiu B, Cosconea S, Jooste V, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology, management and prognosis of colorectal cancer with lung metastases: a 30-year population-based study. Gut. 2010;59:1383-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Khattak MA, Martin HL, Beeke C, Price T, Carruthers S, Kim S, Padbury R, Karapetis CS. Survival differences in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and with single site metastatic disease at initial presentation: results from South Australian clinical registry for advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2012;11:247-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Damiens K, Ayoub JP, Lemieux B, Aubin F, Saliba W, Campeau MP, Tehfe M. Clinical features and course of brain metastases in colorectal cancer: an experience from a single institution. Curr Oncol. 2012;19:254-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Farnell GF, Buckner JC, Cascino TL, O'Connell MJ, Schomberg PJ, Suman V. Brain metastases from colorectal carcinoma. The long term survivors. Cancer. 1996;78:711-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kruser TJ, Chao ST, Elson P, Barnett GH, Vogelbaum MA, Angelov L, Weil RJ, Pelley R, Suh JH. Multidisciplinary management of colorectal brain metastases: a retrospective study. Cancer. 2008;113:158-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Amichetti M, Lay G, Dessì M, Orrù S, Farigu R, Orrù P, Farci D, Melis S; Cagliari Neuro-Oncology Group. Results of whole brain radiation therapy in patients with brain metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Tumori. 2005;91:163-167. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Schoeggl A, Kitz K, Reddy M, Zauner C. Stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases from colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:150-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nozue M, Oshiro Y, Kurata M, Seino K, Koike N, Kawamoto T, Taniguchi H, Todoroki T, Fukao K. Treatment and prognosis in colorectal cancer patients with bone metastasis. Oncol Rep. 2002;9:109-112. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Santini D, Tampellini M, Vincenzi B, Ibrahim T, Ortega C, Virzi V, Silvestris N, Berardi R, Masini C, Calipari N, Ottaviani D, Catalano V, Badalamenti G, Giannicola R, Fabbri F, Venditti O, Fratto ME, Mazzara C, Latiano TP, Bertolini F, Petrelli F, Ottone A, Caroti C, Salvatore L, Falcone A, Giordani P, Addeo R, Aglietta M, Cascinu S, Barni S, Maiello E, Tonini G. Natural history of bone metastasis in colorectal cancer: final results of a large Italian bone metastases study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2072-2077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Giacchetti S, Itzhaki M, Gruia G, Adam R, Zidani R, Kunstlinger F, Brienza S, Alafaci E, Bertheault-Cvitkovic F, Jasmin C, Reynes M, Bismuth H, Misset JL, Lévi F. Long-term survival of patients with unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases following infusional chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and surgery. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:663-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Li WH, Peng JJ, Xiang JQ, Chen W, Cai SJ, Zhang W. Oncological outcome of unresectable lung metastases without extrapulmonary metastases in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3318-3324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, Coatmeur O, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2006;244:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 1005] [Article Influence: 52.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | D'Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265-2281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |