Published online Jul 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i14.3130

Peer-review started: March 28, 2020

First decision: April 24, 2020

Revised: May 4, 2020

Accepted: July 4, 2020

Article in press: July 4, 2020

Published online: July 26, 2020

Processing time: 117 Days and 21.1 Hours

Bezoars can be found anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract. Esophageal bezoars are rare. Esophageal bezoars are classified as either primary or secondary. It is rarely reported that secondary esophageal bezoars caused by reverse migration from the stomach lead to acute esophageal obstruction. Guidelines recommend urgent upper endoscopy (within 24 h) for these impactions without complete esophageal obstruction and emergency endoscopy (within 6 h) for those with complete esophageal obstruction. Gastroscopy is regarded as the mainstay for the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal bezoars.

A 59-year-old man was hospitalized due to nausea, vomiting and diarrhea for 2 d and sudden retrosternal pain and dysphagia for 10 h. He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus for 9 years. Computed tomography revealed dilated lower esophagus, thickening of the esophageal wall, a mass-like lesion with a flocculent high-density shadow and gas bubbles in the esophageal lumen. On gastroscopy, immovable brown bezoars were found in the lower esophagus, which led to esophageal obstruction. Endoscopic fragmentation was successful, and there were no complications. The symptoms of retrosternal pain and dysphagia disappeared after treatment. Mucosal superficial ulcers were observed in the lower esophagus. Multiple biopsy specimens from the lower esophagus revealed nonspecific findings. The patient remained asymptomatic, and follow-up gastroscopy 1 wk after endoscopic fragmentation showed no evidence of bezoars in the esophagus or the stomach.

Acute esophageal obstruction caused by bezoars reversed migration from the stomach is rare. Endoscopic fragmentation is safe, effective and minimally invasive and should be considered as the first-line therapeutic modality.

Core tip: Esophageal bezoars are rare. The reverse migration of gastric bezoars to the esophagus leading to complete esophageal obstruction is even rarer. Our patient presented with sudden retrosternal pain, dysphagia and salivation after severe retching. Esophageal bezoars were diagnosed by computed tomography and gastroscopy. Endoscopic fragmentation using a mouse-tooth clamp and snare was successful, and there were no complications. This case demonstrates that retrograde migration of foreign bodies from the stomach leading to acute esophageal obstruction should be suspected when patients present with sudden retrosternal pain, dysphagia and salivation after retching.

- Citation: Zhang FH, Ding XP, Zhang JH, Miao LS, Bai LY, Ge HL, Zhou YN. Acute esophageal obstruction caused by reverse migration of gastric bezoars: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(14): 3130-3135

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i14/3130.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i14.3130

Esophageal obstruction is often caused by tumors, severe inflammation, cysts and malformations, which manifests as slow and progressive clinical symptoms. Acute esophageal obstruction is frequently caused by food impaction or other foreign bodies eaten by mistake and are rarely caused by retrograde migration of secondary foreign bodies from stomach[1]. Bezoars are commonly seen in the stomach but can be found anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract. Compared with gastric bezoars, esophageal bezoars are more likely to cause symptoms of gastrointestinal obstruction[2,3]. The reverse migration of gastric bezoars to the esophagus leading to acute obstruction is rare with only a few reports in the literature[4,5]. Here we report a case of acute esophageal obstruction caused by the reverse migration of gastric bezoars after an episode of retching, and we review the literature on esophageal bezoars.

A 59-year-old man presented to our hospital complaining of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea for 2 d and both retrosternal pain and dysphagia for 10 h.

The patient developed nausea and vomiting after eating overnight food 2 d previously with vomiting and retching more than 10 times/d. Vomitus consisted of intragastric mucus accompanied by intermittent abdominal pain and diarrhea with yellow watery stool approximately 10 times/d. The patient received a proton pump inhibitor and intravenous fluid rehydration in the outpatient clinic. His symptoms of diarrhea were relieved, but there was still nausea. The patient developed sudden retrosternal pain, dysphagia and salivation 10 h previously after severe retching. His symptoms persisted, and he was admitted to the Department of Digestive Internal Medicine in our hospital.

The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus for 9 years and was treated with an injection of NovoMix30; however, his blood glucose was poorly controlled. He liked to eat persimmon. He had no history of gastric surgery.

The patient had no pertinent family history.

The patient’s vital signs were stable. He had epigastric tenderness and excessive salivation.

Blood analysis revealed normal white blood cell count, elevated neutrophils (90.0%), and normal hematocrit and platelet count. Serum C-reactive protein was increased at 22.0 mg/dL (normal range < 0.83 mg/dL). The plasma levels of myocardial enzyme were normal. Other blood biochemistries were normal with the exception of fasting blood glucose, which was 7.82 mmol/L (normal range 3.2-6.2 mmol/L). Electrocardiogram was also normal.

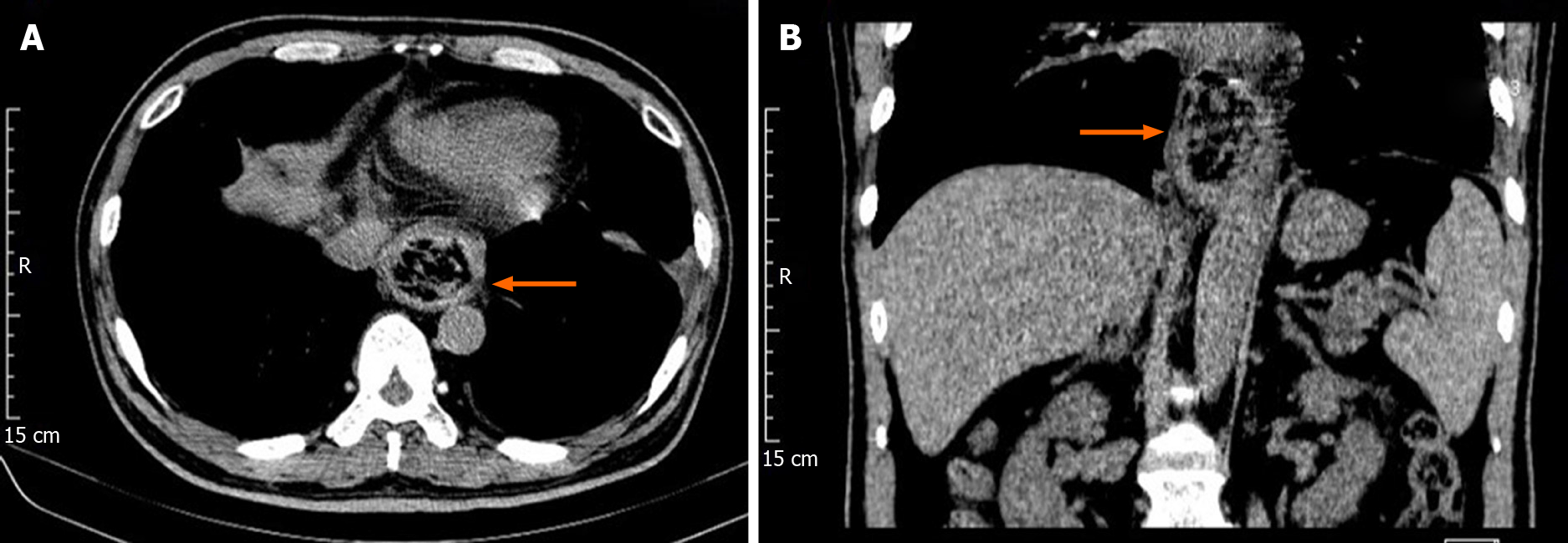

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed dilated lower esophagus, thickening of the esophageal wall, a mass-like lesion with a flocculent high-density shadow and gas bubbles in the esophageal lumen (5 cm long and 4.2 cm in diameter). The CT value was 106-53 HU (Figure 1A and B).

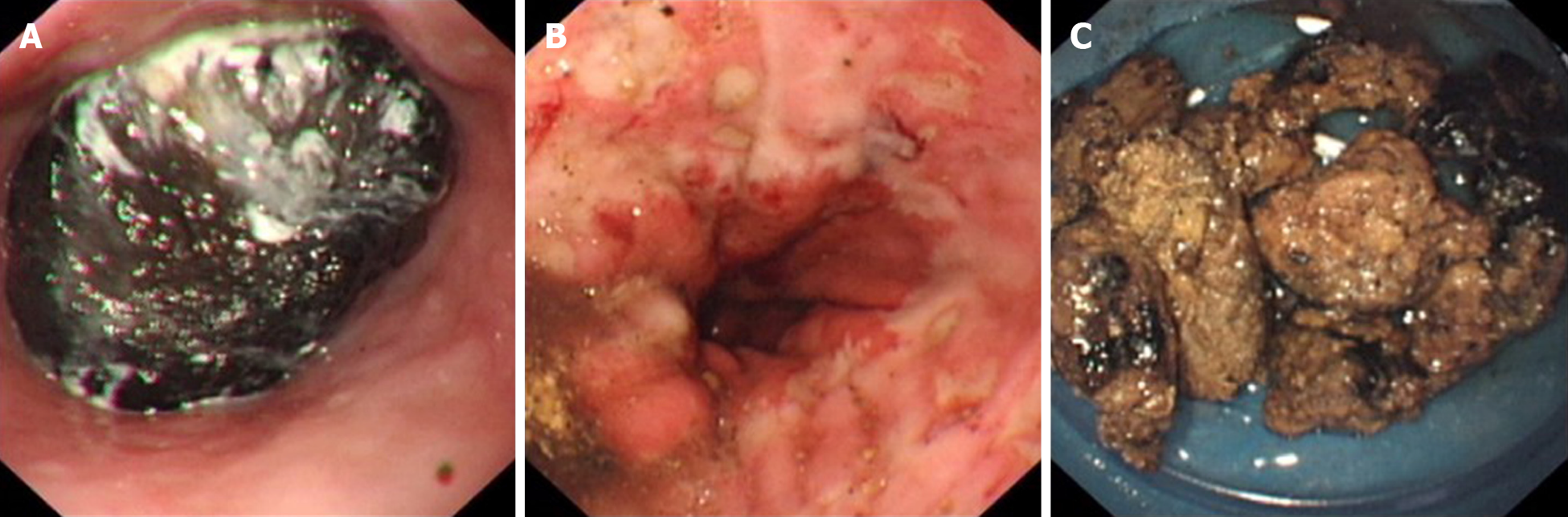

The patient underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which showed large immovable brown bezoars in the lower esophagus, which led to esophageal obstruction (Figure 2A). The endoscope was unable to pass the bezoars to enter the stomach. The patient was treated with endoscopic fragmentation, and multiple mucosal edema, erosions and superficial ulcers were observed in the lower esophagus during the treatment (Figure 2B). Multiple biopsy specimens were obtained from these sites, and examination of these specimens revealed nonspecific findings.

The final diagnosis was secondary esophageal bezoars.

Despite difficulties, we attempted endoscopic esophageal bezoar fragmentation. After installing a hard transparent cap on the head of the endoscope, the bezoars were endoscopically fragmented using a mouse-tooth clamp and snare. The esophageal bezoars were fragmented step by step, and then fragments were removed using a basket. When the bezoars could move freely in the esophagus, they were pushed into the stomach. The bezoars were fragmented again and removed using a basket (Figure 2C). Some small fragments remained in the stomach. Coca-Cola was given to the patient in an attempt to dissolve the remaining bezoar fragments in the stomach and to prevent formation of large bezoars again[6].

Following endoscopic fragmentation, retrosternal pain and dysphagia disappeared. The patient had no obvious symptoms of small intestinal obstruction such as abdominal distension and abdominal pain. Follow-up endoscopy 1 wk later, showed no evidence of foreign bodies in the esophagus or the stomach. The patient was advised not to eat persimmons and control his blood sugar.

Bezoars, which are accumulations of foreign material in the gastrointestinal tract, can be divided according to their composition into four types: Phytobezoar, trichobezoar, pharmacobezoar and lactobezoar. Phytobezoar is the most common type[7]. Phytobezoars are composed of indigestible fibers (cellulose, hemicellulose, tannin and lignin) from vegetables and fruits[8].

Bezoars are more commonly seen in the stomach, and esophageal bezoars are a rare but distinct clinical entity. Under normal circumstances, with esophageal self- clearance mechanisms, such as esophageal peristalsis, saliva, and erect posture, food passes through the esophagus quickly and does not usually remain in the esophagus. This prevents the formation of bezoars. Esophageal bezoars are classified as either primary or secondary. Primary esophageal bezoars are mainly found in patients with structural or functional abnormalities of the esophagus, including achalasia, progressive systemic sclerosis, diffuse esophageal spasm, myasthenia gravis and Guillain Barre syndrome[9], especially if they are accompanied by critical illnesses that require nasal feeding or patients with mental disorders[5,10,11]. Secondary bezoars originate in the stomach and are regurgitated into the esophagus when severe nausea or retching occur and become lodged in the esophagus causing acute esophageal obstruction[4], which was the most likely cause in our patient.

Before developing sudden retrosternal pain and dysphagia, our patient had no difficulty in swallowing with only occasional slight bloating. Due to his long history of diabetes, he usually eats vegetables and low-sugar fruits in order to control his blood sugar, and he especially likes to eat persimmons, which may have been the major risk factor for the formation of bezoars in this patient. Persimmon, a fleshy fibrous fruit, and dried persimmon are consumed more frequently in the north of China. The water-soluble tannin shibutol (a phlobotannin) is produced by certain cells in the skin of the persimmon and is composed of phloroglucin and gallic acid, which can generate phytobezoars especially in an empty stomach[12].

Diabetes mellitus was reported to be a predisposing factor in phytobezoar formation due to delayed gastric emptying[13]. Up to 50% of patients with diabetes mellitus have delayed gastric emptying and associated gastropathy[13]. Indigestible cellulose, such as the skin and seeds of fruits and vegetables may remain longer and easily form bezoars in the acidic environment of the stomach.

CT scanning and gastroscopy may be used as the main methods in diagnostic work-up. CT is a reliable and accurate method for diagnosing gastrointestinal bezoars and exhibits characteristic images[14]. Gastroscopy is the main tool for the confirmation of the presence and location of bezoars. The treatment options for upper gastrointestinal bezoars include endoscopic fragmentation, dissolution therapy, surgical exploration and removal of the bezoars[5]. Various chemical compounds have been used to dissolve bezoars including carbonated drinks, acetylcysteine and enzymatic compounds such as pancreatic enzyme[15,16]. However, this non-invasive treatment option does not seem to be appropriate for esophageal bezoars, presenting as a case of acute obstruction, such as in our patient. Surgical treatment can completely remove bezoars and relieve the obstruction; however, surgery is associated with a high risk of trauma, patients recover slowly and it is only recommended in complicated cases that cannot be resolved endoscopically or after unsuccessful attempts at endoscopic recovery[17]. Thus, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is regarded as the mainstay for the treatment of esophageal bezoars as it is safe, highly efficacious and minimally invasive[5]. Although endoscopic treatment of bezoars is safe, complications may occur, and the incidence of complications is increased due to the relative pressure in the narrow esophageal space. To obtain an optimal effect, the choice of a specific treatment method depends on the morphologic characteristics of the bezoar as well as the patient’s clinical condition. Based on our patient’s medical history, symptoms and examination results, endoscopic fragmentation was performed cautiously. Mouse-tooth clamp, polypectomy snares and a basket were used to fragment and evacuate the bezoars. The endoscopic fragmentation was successful with no complications. No other lesions in the esophagus were found on esophageal biopsy and follow-up endoscopy.

Acute secondary esophageal bezoars like this case occur suddenly, together with obvious painful symptoms and requires diagnosis and treatment as soon as possible. Current guidelines recommend urgent upper endoscopy (within 24 h) for food impactions without complete esophageal obstruction and emergency endoscopy (within 6 h) for those with complete esophageal obstruction[17,18]. This patient underwent endoscopic fragmentation immediately after definite diagnosis, which relieved the patient’s pain and avoided further esophageal injury.

Acute esophageal obstruction caused by bezoars reversed migration from the stomach is rare. Secondary esophageal bezoars cause acute esophageal obstruction and should be suspected when patients present with sudden retrosternal pain, dysphagia and salivation after retching. Patients with this condition require urgent treatment, and endoscopic therapy should be the first-line therapeutic modality.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fugazza A, Marteau P S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Lukish JR, Eichelberger MR, Henry L, Mohan P, Markle B. Gastroesophageal intussusception: a new cause of acute esophageal obstruction in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1125-1127. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Zhang MM, Jiang DL, Li WL, Lv M, Zhan SH. Esophageal calculus: Report of two cases. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2013;21:2367-2368. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhang SJ, Chen X, Wang R, Ma RJ, Hou B, Zhao DY. Endoscopic features and treatment of digestive tract calculi: a report of 103 cases. Zhonghua Linchuang Yishi Zazhi. 2015;9:168-170. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Pitiakoudis M, Tsaroucha A, Mimidis K, Constantinidis T, Anagnostoulis S, Stathopoulos G, Simopoulos C. Esophageal and small bowel obstruction by occupational bezoar: report of a case. BMC Gastroenterol. 2003;3:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chaudhry I, Asban A, Kazoun R, Khurshid I. Lithobezoar, a rare cause of acute oesophageal obstruction: surgery after failure of endoscopic removal. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ladas SD, Triantafyllou K, Tzathas C, Tassios P, Rokkas T, Raptis SA. Gastric phytobezoars may be treated by nasogastric Coca-Cola lavage. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:801-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iwamuro M, Okada H, Matsueda K, Inaba T, Kusumoto C, Imagawa A, Yamamoto K. Review of the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal bezoars. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:336-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 8. | Zhang RL, Yang ZL, Fan BG. Huge gastric disopyrobezoar: a case report and review of literatures. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:152-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim KH, Choi SC, Seo GS, Kim YS, Choi CS, Im CJ. Esophageal bezoar in a patient with achalasia: case report and literature review. Gut Liver. 2010;4:106-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tawfic QA, Bhakta P, Date RR, Sharma PK. Esophageal bezoar formation due to solidification of enteral feed administered through a malpositioned nasogastric tube: case report and review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2012;50:188-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Díaz de la Lastra E, Trapero M, Cantero J, Monasterio F. Esophageal obstruction in critically ill patients: a potential severe complication of enteral nutrition. Endoscopy. 2005;37:786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gayà J, Barranco L, Llompart A, Reyes J, Obrador A. Persimmon bezoars: a successful combined therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:581-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ahn YH, Maturu P, Steinheber FU, Goldman JM. Association of diabetes mellitus with gastric bezoar formation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:527-528. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ripollés T, García-Aguayo J, Martínez MJ, Gil P. Gastrointestinal bezoars: sonographic and CT characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:65-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee BJ, Park JJ, Chun HJ, Kim JH, Yeon JE, Jeen YT, Kim JS, Byun KS, Lee SW, Choi JH, Kim CD, Ryu HS, Bak YT. How good is cola for dissolution of gastric phytobezoars? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2265-2269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gupta R, Share M, Pineau BC. Dissolution of an esophageal bezoar with pancreatic enzyme extract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:96-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Birk M, Bauerfeind P, Deprez PH, Häfner M, Hartmann D, Hassan C, Hucl T, Lesur G, Aabakken L, Meining A. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48:489-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher LR, Fukami N, Harrison ME, Jain R, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Maple JT, Sharaf R, Strohmeyer L, Dominitz JA. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1085-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |