Published online Jul 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i14.3031

Peer-review started: March 19, 2020

First decision: April 22, 2020

Revised: May 25, 2020

Accepted: July 16, 2020

Article in press: July 16, 2020

Published online: July 26, 2020

Processing time: 126 Days and 23.5 Hours

End-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the common lung diseases referred for lung transplantation. According to the international society of heart and lung transplantation, 30% of all lung transplantations are carried out for COPD alone. When compared to bilateral lung transplant, single-lung transplant (SLT) has similar short-term and medium-term results for COPD. For patients with severe upper lobe predominant emphysema, lung volume reduction surgery is an excellent alternative which results in improvement in functional status and long-term mortality. In 2018, endobronchial valves were approved by the Food and Drug Administration for severe upper lobe predominant emphysema as they demonstrated improvement in lung function, exercise capacity, and quality of life. However, the role of endobronchial valves in native lung emphysema in SLT patients has not been studied.

We describe an unusual case of severe emphysema who underwent a successful SLT 15 years ago and had gradual worsening of lung function suggestive of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. However, her lung function improved significantly after a spontaneous pneumothorax of the native lung resulting in auto-deflation of large bullae.

This case highlights the clinical significance of native lung hyperinflation in single lung transplant recipient and how spontaneous decompression due to pneumothorax led to clinical improvement in our patient.

Core tip: Native lung hyperinflation can lead to significant transplanted lung dysfunction and worsening of clinical symptoms. While lung volume reduction surgery has been identified as an approach to improve quality of life in patient with severe upper-lobe predominant emphysema, its benefits in single lung transplant patient is limited to case reports and small retrospective studies. No prior case has been described of an auto-lung volume reduction of native lung in single lung transplant patient. In our patient, a spontaneous pneumothorax in the emphysematous native lung led to automatic lung volume reduction and significant clinical improvement. This case highlights the importance of identifying appropriate patient selection for lung volume reduction surgery when chronic lung allograft dysfunction has been ruled out in transplanted lung and patient has significant symptom burden and evidence of native lung hyperinflation.

- Citation: Deshwal H, Ghosh S, Hogan K, Akindipe O, Lane CR, Mehta AC. Spontaneous pneumothorax in a single lung transplant recipient-a blessing in disguise: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(14): 3031-3038

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i14/3031.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i14.3031

End-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the common lung diseases referred for lung transplantation[1]. Indications for a lung transplant in COPD include poor functional status (BODE index of 7-10), severely reduced lung function (forced expiratory volume 1 < 20% of predicted), hypercapnia (PaCo2 ≥ 55 mm Hg) and hypoxemia with decreased diffusion capacity (DLCO < 20%)[2]. According to the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation, 30.6% (18233/6400) of all adult lung transplants have been carried out for COPD alone[3]. When compared to bilateral lung transplant (BLT), single-lung transplant (SLT) has similar short-term and medium-term results for COPD patients[1].

For patients with severe upper lobe predominant emphysema, lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) is an excellent alternative, which results in an improvement in functional status and long term mortality[4]. In 2018, endobronchial valves were approved by the Food and Drug Administration for severe upper lobe predominant emphysema as they demonstrated improvement in lung function, exercise capacity, and quality of life[5]. However, the role of endobronchial valves in native lung emphysema in SLT patients has not been studied.

We describe an unusual case of severe emphysema who underwent a successful SLT 15 years ago and had a gradual worsening of lung function suggestive of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. However, her lung function improved significantly after a spontaneous pneumothorax of the native lung resulting in the auto-deflation of large bullae.

A 74-year-old female presented to the hospital with acute left-sided chest pain, neck swelling and shortness of breath for one hour. In the emergency department, she appeared in respiratory distress and was placed on supplemental oxygen.

She was in her usual state of health, when she developed acute onset left-sided severe chest pain that was sharp in nature and non-radiating. It was worse with inspiration and had no relieving factors. It was associated with significant shortness of breath and neck swelling that prompted her to seek medical attention.

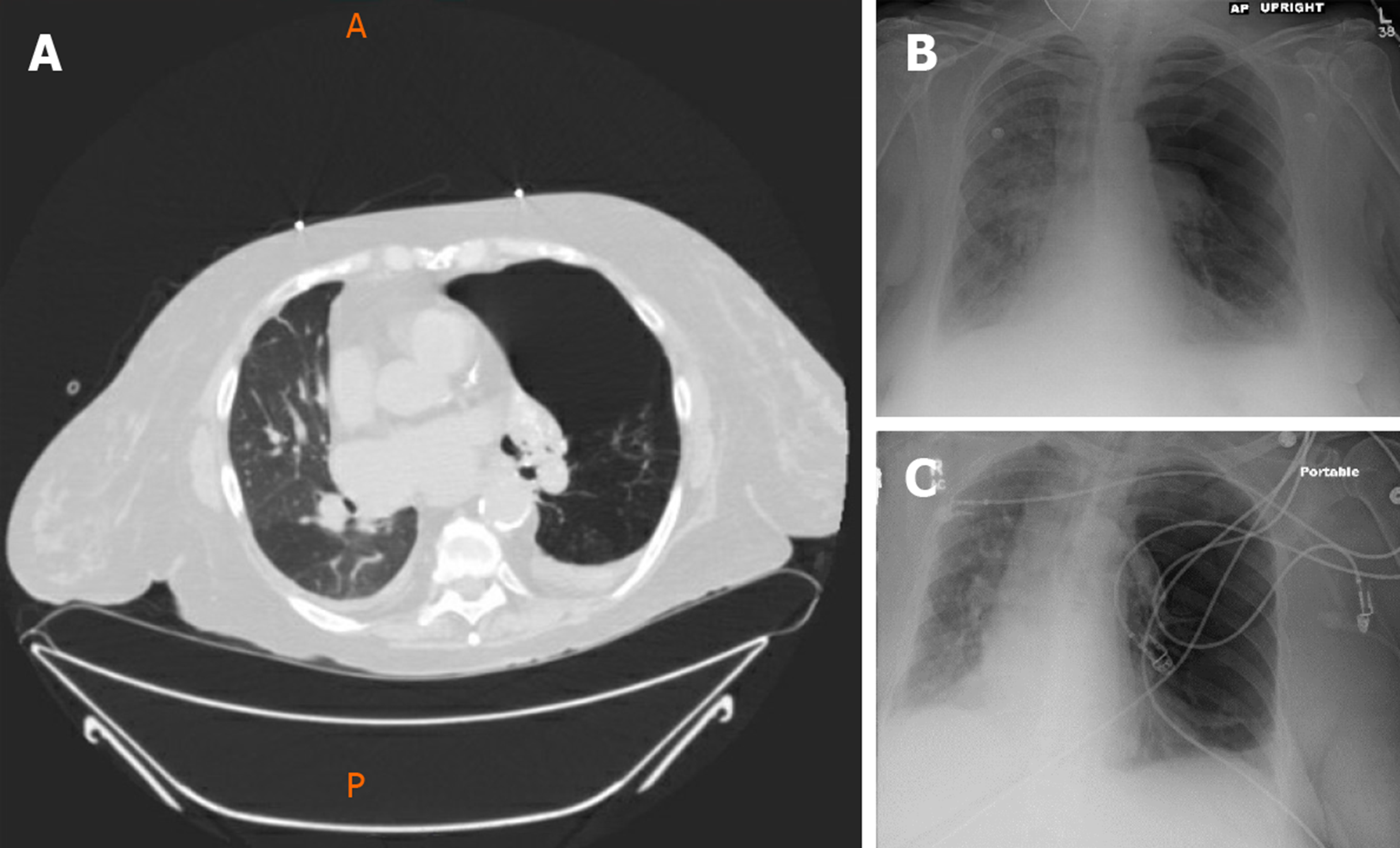

She had a past medical history of End-Stage COPD (FEV1-15%) with severe diffuse emphysema and underwent a successful single right lung transplant in July 2004 (Figure 1). Her medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone for immunosuppression and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, valacyclovir and itraconazole for Pneumocystis, cytomegalovirus and fungal infections prophylaxis respectively. Her peak FEV1 on post-operative follow up was 65%. She had no evidence of acute rejection on early surveillance bronchoscopies.

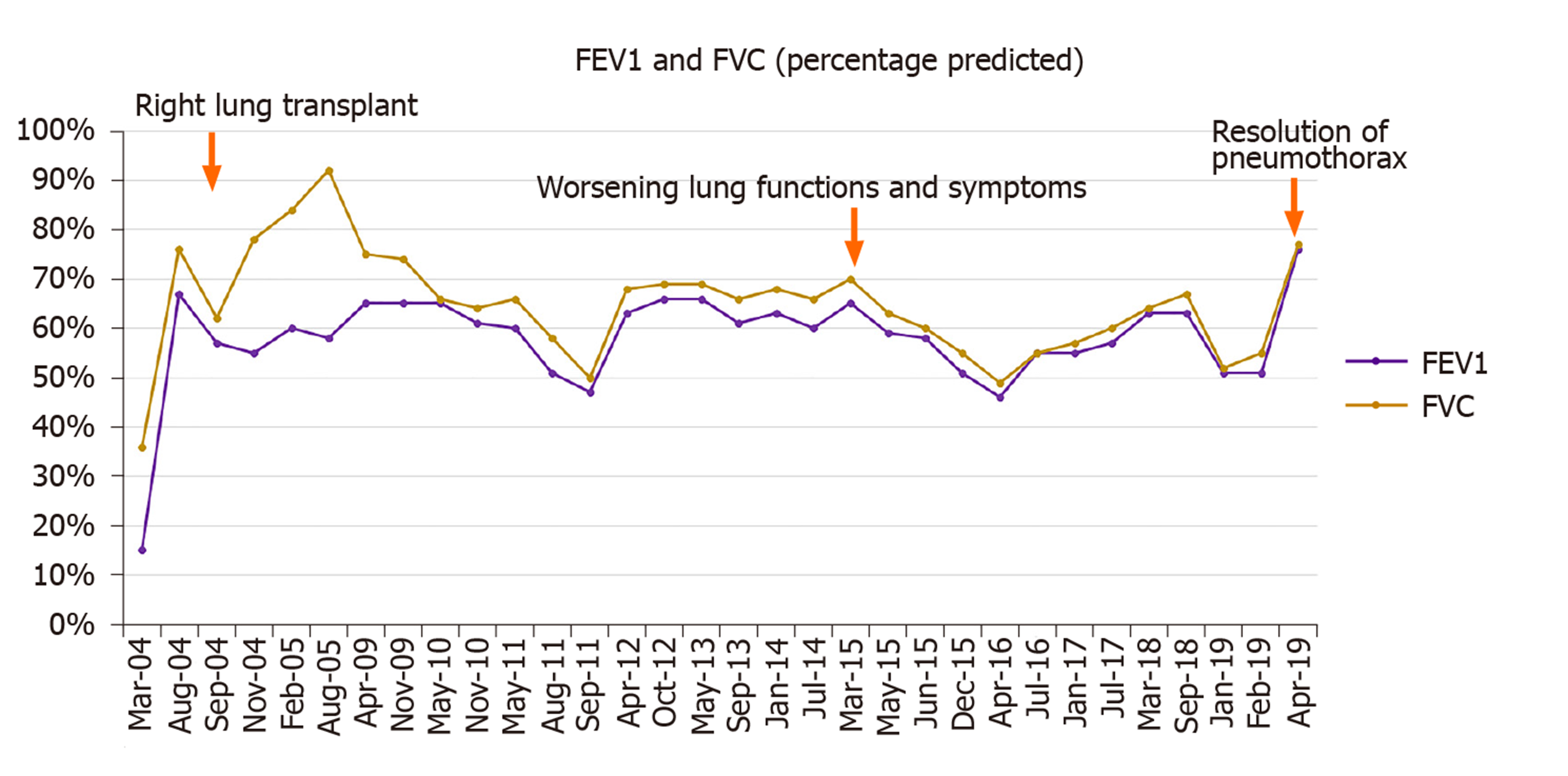

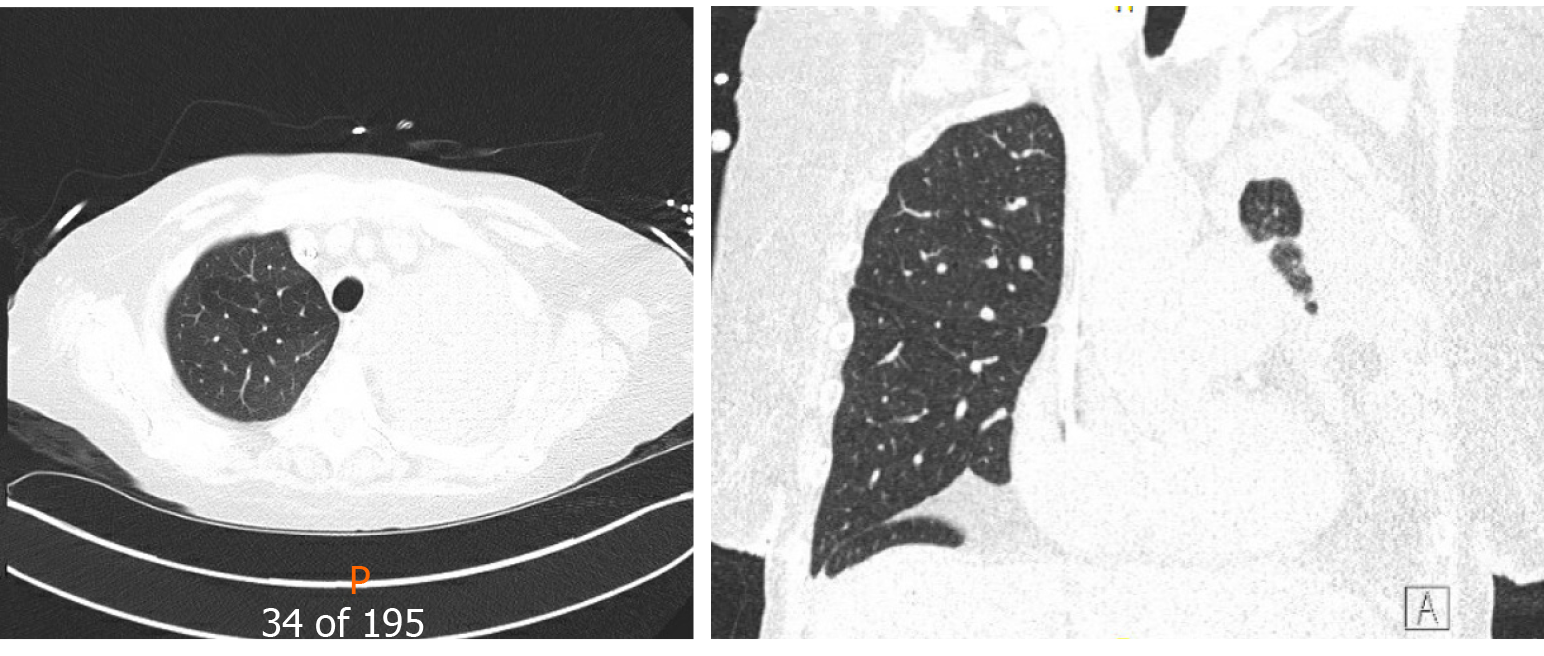

Unfortunately, in 2015, eleven years following the transplantation, she developed acute complicated diverticulitis requiring urgent right hemicolectomy and ileostomy. Her postoperative course was complicated by frequent episodes of dehydration and acute kidney injury. She also had two bouts of lower lobe pneumonia involving the allograft and acute tubular necrosis that eventually progressed to chronic kidney disease. On subsequent follow-ups, she complained of worsening dyspnea and cough. Her spirometry revealed a gradual decline in FEV1 from a peak of 65% of predicted to a nadir of 51% (Figure 2). In November 2018, she presented with worsening renal function, volume overload, and recurrent left-sided pleural effusions (Figure 3). Hemodialysis was initiated, and therapeutic thoracentesis was performed with 1200 cc transudative fluid removal. Despite the optimization of her volume status, she continued to have worsening dyspnea and lung function along with recurrent left-sided pleural effusions. We excluded ongoing acute cellular rejection by transbronchial biopsies, and a diagnosis of chronic lung allograft dysfunction prompted replacing mycophenolate with sirolimus. She also had a tunneled pleural catheter placed in left pleural space for recurrent effusions. She was placed on inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting bronchodilators with minimal improvement. By December 2018, she was on supplemental oxygen at 4 L/min by nasal cannula for chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure.

She had no significant family history. Prior to lung transplantation she was a lifelong smoker with 40 pack year smoking history and subsequently quit in 2003. She denied any illicit drug use or alcohol use.

Her blood pressure was 90/60 mmHg and pulse was 100/min and oxygen saturation was 86% on 4 liters of oxygen via nasal cannula. On inspection she was using accessory respiratory muscles and appeared in respiratory distress. She had significant subcutaneous emphysema with crepitus extending up to the neck. On auscultation of the chest, there were absent breath sounds on the left hemithorax.

Initial laboratory examination was largely insignificant with normal hemoglobin, white blood cell count, platelets, liver function and electrolytes. She had history of chronic kidney disease and her blood urea nitrogen and creatinine were 48 mg/dL and 2.3 mg/dL respectively.

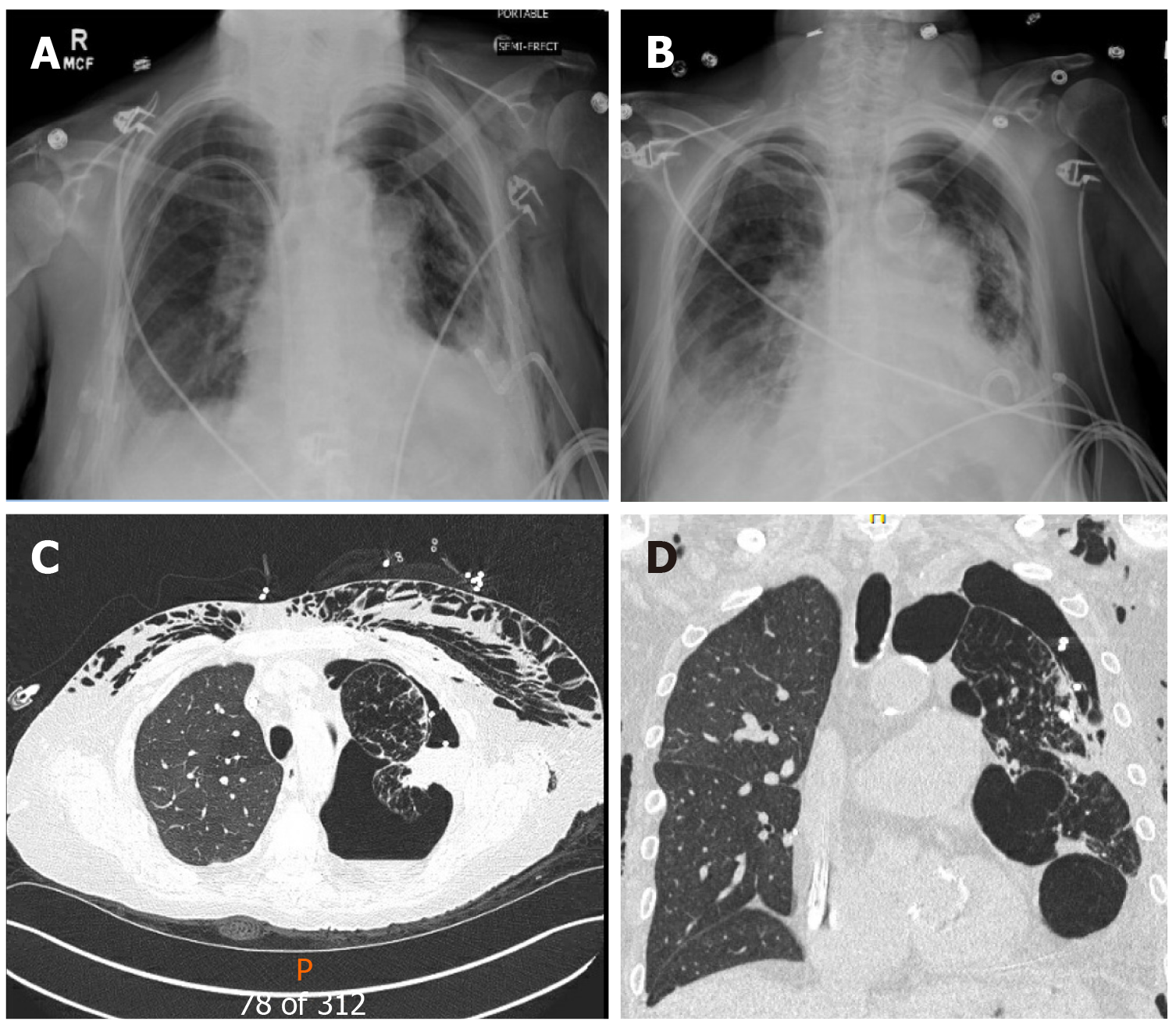

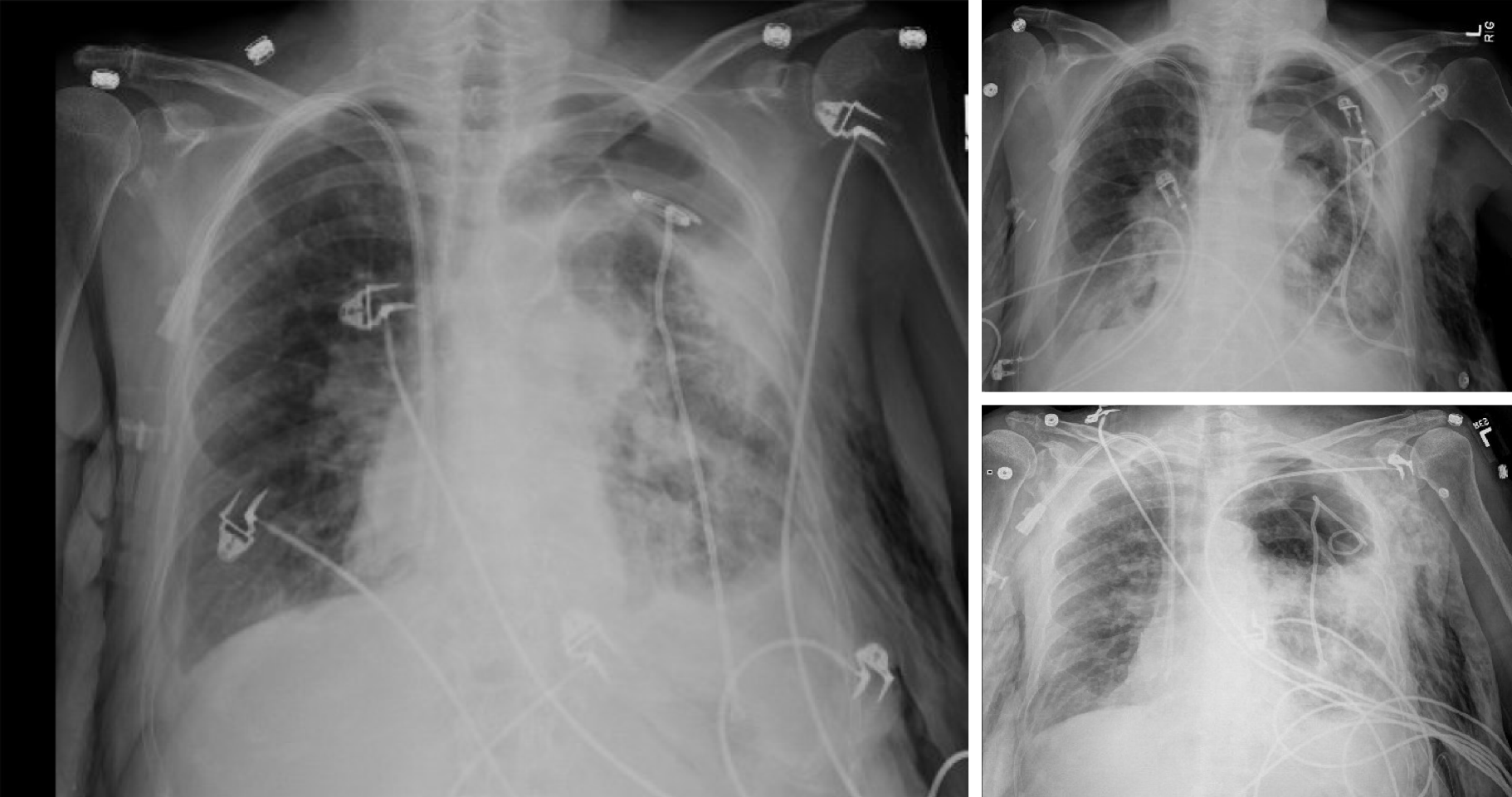

A chest radiograph revealed a large left hydropneumothorax with an indwelling pigtail drainage catheter in the left pleural space. The native left lung was partially collapsed. There was subcutaneous emphysema in the left chest wall (Figure 4).

She was promptly diagnosed with a spontaneous pneumothorax due to rupture of a large bullae in her native emphysematous lung.

We placed her pre-existing tunneled pleural catheter to suction with subsequent improvement in her symptoms. She further needed an additional pigtail pleural catheter placement in the left pleural space for a persistent hydropneumothorax. However, she became extremely dyspneic when taken off suction, prompting the placement of a Heimlich valve to the pleural catheter. Repeat chest x-ray demonstrated improvement in hydropneumothorax, and both pigtail and pleural catheters were clamped (Figure 5). Just before discharge, she again experienced respiratory distress, and both catheters were placed back on suction. This time, her symptoms improved significantly, and the indwelling tunneled pleural catheter was removed. She was discharged home with the pigtail catheter in-situ. Remarkably, on her way to a follow-up appointment, her pigtail catheter fell out of the pleural space, with no clinical consequences.

On a follow-up visit in April 2019, she reported a marked improvement in her dyspnea and no longer required supplemental oxygen. At the same time, she demonstrated a 25% improvement in her FEV1 (51% to 76%) (Figure 2), and the chest x-ray revealed the expansion of the right allograft as a result of marked deflation of large bullae in the left lung (Figure 6).

COPD is one of the common indications for lung transplantation. Over 18233 transplants have been carried out for COPD alone[3]. A single lung transplant may be considered for COPD as it offers shorter waitlist time, shorter surgical time, and technical ease. Single lung transplant for COPD has similar short-term and medium-term outcomes compared to BLT. However, long term outcomes are better with BLT[3]. Several factors may play a role in this difference, with a critical factor being the diseased native lung.

Native lung complications can develop in up to 13.8% of patients with SLT and are associated with worse prognosis[6]. Infections and malignancy may lead to alterations in the immunosuppressive regimen, and as a result, put the transplanted lung at risk of rejection. The emphysematous native lung can also compress the allograft and lead to its decreased perfusion, subsequently leading to graft dysfunction[7].

King et al[6] studied the role of native lung pneumonectomy in SLT patients with native lung complications[6]. They found a trend towards improved survival in patients undergoing pneumonectomy compared to those managed non-surgically (4.3 years vs 2.4 years, respectively). However, the result did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.128)[6]. Native lung hyperinflation may lead to impairment of gas exchange and worsen respiratory function among recipients of SLTx for emphysema. Several cases have been described with improvement in lung function, exercise capacity, and symptoms after lung volume reduction surgery, bullectomy, or pneumonectomy of the native lung[8,9].

While the role of LVRS is well established in patients with severe upper lobe predominant emphysema, some case reports and retrospective studies highlight the benefit of LVR in severe emphysema of native lung in SLT patients[4,10,11]. However, LVRS is associated with significant morbidity (20% to 29.8% pulmonary and cardiac morbidity respectively), and operative mortality (5.5%) and careful patient selection is warranted[12].

Less invasive approaches have since been described for lung volume reduction in severe emphysema. The use of bronchoscopic LVR has also demonstrated efficacy in improving lung function, exercise capacity, and quality of life. The use of endobronchial one-way valve placement has led to significant improvement in exercise capacity and lung function[13,14]. A meta-analysis conducted by Iftikhar et al[15] demonstrated the non-inferiority of Bronchoscopic LVR compared to LVRS[15]. In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved the endobronchial valve Zephyr (Pulmonx. Inc., Palo Alto, CA, United States) for Bronchoscopic LVR in severe emphysema[16]. Other novel techniques such as lung volume reduction coils, bronchial thermal vapor, and installation of bio-degradable gel or polymers have also demonstrated efficacy in severe diffuse emphysema, yet, they remain experimental in the United States[17-19]. Perch et al[20] conducted a case series of 14 patients with native lung hyperinflation in SLT patients and demonstrated significant improvement in lung function and symptoms with endobronchial valves[20]. The study demonstrated the feasibility of endoscopic treatment for native lung hyperinflation in SLT patients, but prospective trials are required to assess its real efficacy. Our case highlights a phenomenon of auto-deflation of a large bulla leading to spontaneous lung volume reduction of the native lung and subsequent improvement in allograft lung function, thus highlighting the importance of considering LVR in SLT patients. While native lung hyperinflation was considered a possibility for her clinical decline, this phenomenon occurred even before considering her for LVR. Surgical lung volume reduction may be challenging in these patients due to co-morbid conditions and prior thoracic surgery (SLT), but bronchoscopic LVR is an attractive alternative. The real challenge lies in patient selection and identifying which patient will benefit most from it. Pulmonary function tests alone are unable to distinguish CLAD from native lung hyperinflation as a cause of a drop in lung function. The presence of CLAD in allograft would also reduce the likelihood that the graft will expand and improve function after native lung LVR. From our experience, certain clinical features can assist in patient selection for LVR in SLT patients. The patient should have apical predominant severe emphysema in the native lung. A SPECT scan can help identify areas with perfusion and poor ventilation that can be targeted for LVR. It is imperative to rule out CLAD in the transplanted lung before considering LVR.

Like any other intervention, bronchoscopic LVR is associated with certain complications that include valve migration, post-obstructive pneumonia, pneumothorax, and bleeding[20]. It is thus imperative to discuss risks and benefit with the patient in detail.

Native lung pathology can impede the function of the allograft and lead to an erroneous diagnosis of allograft rejection or chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Spontaneous pneumothorax involving the native lung is yet another sequela of SLT. In our patient, hyperinflation and air trapping in the native emphysematous lung led to chronic respiratory failure following SLT. Incidentally, the patient developed a spontaneous pneumothorax with a natural volume reduction of the native lung leading to improvement in overall lung function. Among symptomatic recipients of SLT, the contribution of native lung hyperinflation and air trapping should prompt consideration of endobronchial valve therapy albeit with appropriate patient selection criteria.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhang WB S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Aziz F, Penupolu S, Xu X, He J. Lung transplant in end-staged chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients: a concise review. J Thorac Dis. 2010;2:111-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Orens JB, Estenne M, Arcasoy S, Conte JV, Corris P, Egan JJ, Egan T, Keshavjee S, Knoop C, Kotloff R, Martinez FJ, Nathan S, Palmer S, Patterson A, Singer L, Snell G, Studer S, Vachiery JL, Glanville AR; Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2006 update--a consensus report from the Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:745-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 781] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chambers DC, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb SB, Hayes D, Kucheryavaya AY, Toll AE, Khush KK, Levvey BJ, Meiser B, Rossano JW, Stehlik J; International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth adult lung and heart-lung transplant report-2018; Focus theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:1169-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 50.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van Agteren JE, Carson KV, Tiong LU, Smith BJ. Lung volume reduction surgery for diffuse emphysema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD001001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Valipour A. Valve therapy in patients with emphysematous type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): from randomized trials to patient selection in clinical practice. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:S2780-S2796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | King CS, Khandhar S, Burton N, Shlobin OA, Ahmad S, Lefrak E, Barnett SD, Nathan SD. Native lung complications in single-lung transplant recipients and the role of pneumonectomy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:851-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Malchow SC, McAdams HP, Palmer SM, Tapson VF, Putman CE. Does hyperexpansion of the native lung adversely affect outcome after single lung transplantation for emphysema? Preliminary findings. Acad Radiol. 1998;5:688-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Novick RJ, Menkis AH, Sandler D, Garg A, Ahmad D, Williams S, McKenzie FN. Contralateral pneumonectomy after single-lung transplantation for emphysema. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;52:1317-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Le Pimpec-Barthes F, Debrosse D, Cuenod CA, Gandjbakhch I, Riquet M. Late contralateral lobectomy after single-lung transplantation for emphysema. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Destors M, Aniwidyaningsih W, Jankowski A, Pison C. Endoscopic volume reduction before or after lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:897-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pato O, Rama P, Allegue M, Fernández R, González D, Borro JM. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction in a single-lung transplant recipient with natal lung hyperinflation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:1979-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Naunheim KS, Wood DE, Krasna MJ, DeCamp MM, Ginsburg ME, McKenna RJ, Criner GJ, Hoffman EA, Sternberg AL, Deschamps C; National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Predictors of operative mortality and cardiopulmonary morbidity in the National Emphysema Treatment Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:43-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Valipour A, Burghuber OC. An update on the efficacy of endobronchial valve therapy in the management of hyperinflation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2015;9:294-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Valipour A, Slebos DJ, Herth F, Darwiche K, Wagner M, Ficker JH, Petermann C, Hubner RH, Stanzel F, Eberhardt R; IMPACT Study Team. Endobronchial Valve Therapy in Patients with Homogeneous Emphysema. Results from the IMPACT Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:1073-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Iftikhar IH, McGuire FR, Musani AI. Efficacy of bronchoscopic lung volume reduction: a meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:481-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zephyr® Endobronchial Valve System - P180002. 2018. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/recently-approved-devices/zephyrr-endobronchial-valve-system-p180002/. |

| 17. | Deslee G, Klooster K, Hetzel M, Stanzel F, Kessler R, Marquette CH, Witt C, Blaas S, Gesierich W, Herth FJ, Hetzel J, van Rikxoort EM, Slebos DJ. Lung volume reduction coil treatment for patients with severe emphysema: a European multicentre trial. Thorax. 2014;69:980-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Snell G, Herth FJ, Hopkins P, Baker KM, Witt C, Gotfried MH, Valipour A, Wagner M, Stanzel F, Egan JJ, Kesten S, Ernst A. Bronchoscopic thermal vapour ablation therapy in the management of heterogeneous emphysema. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1326-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Milenkovic B, Janjic SD, Popevic S. Review of lung sealant technologies for lung volume reduction in pulmonary disease. Med Devices (Auckl). 2018;11:225-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Perch M, Riise GC, Hogarth K, Musani AI, Springmeyer SC, Gonzalez X, Iversen M. Endoscopic treatment of native lung hyperinflation using endobronchial valves in single-lung transplant patients: a multinational experience. Clin Respir J. 2015;9:104-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |