Published online Jun 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2597

Peer-review started: March 2, 2020

First decision: April 22, 2020

Revised: May 9, 2020

Accepted: May 21, 2020

Article in press: May 21, 2020

Published online: June 26, 2020

Processing time: 114 Days and 20.8 Hours

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a common infection in liver transplant recipients, which is related to chronic rejection and biliary complications. It is often diagnosed based on serum CMV-DNA or CMV pp65. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the successful treatment of occult CMV cholangitis in a pediatric liver transplantation (LT) recipient.

A 7-mo-old baby girl received LT due to biliary atresia and cholestasis cirrhosis. At 1 mo following LT, the patient suffered from aggravated jaundice with no apparent cause. As imaging results showed intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation, the patient was diagnosed with biliary complications and percutaneous cholangiography and biliary drainage was performed. However, there was little biliary drainage and her liver function deteriorated. CMV-DNA was isolated from the bile with the surprising outcome that 3 × 106 copies/mL were present, whereas the CMV-DNA in serum was negative. Following antiviral therapy with ganciclovir, she gradually recovered and bilirubin decreased to normal levels. During the 4-year follow-up period, her liver function remained normal.

Bile CMV sampling can be used for the diagnosis of occult CMV infection, especially in patients with negative serum CMV-DNA and CMV pp65. Testing for CMV in the biliary tract may serve as a novel approach for the diagnosis of cholestasis post-LT. Timely diagnosis and treatment will decrease the risk of graft loss.

Core tip: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is related to chronic rejection and biliary complications that can occur after liver transplantation. Although often treated prophylactically, CMV infection and CMV disease still remain a challenge. Here we report the successful treatment of occult CMV cholangitis in a pediatric liver transplantation recipient. Our study suggests that testing for CMV in the biliary tract especially in patients with negative serum CMV-DNA and CMV pp65 may be a novel approach for the diagnosis of occult CMV cholangitis after pediatric liver transplantation. Timely diagnosis and treatment will decrease the risk of graft loss.

- Citation: Liu Y, Sun LY, Zhu ZJ, Qu W. Novel approach for the diagnosis of occult cytomegalovirus cholangitis after pediatric liver transplantation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(12): 2597-2602

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i12/2597.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2597

Biliary complications represent one of the most prevalent problems after liver transplantation (LT) and are the main cause of liver retransplantation[1,2]. Biliary complications post-LT can be the result of many factors, including surgical techniques, local ischemia, infection and immune injury.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a common infection in liver transplant recipients. It can occur in the liver, lungs, gut and even present as a systemic infection[3]. CMV can be sensitively detected in body fluids and biopsies than in the blood. A study found that some patients were positive for biliary CMV, but negative for serum pp65 and CMV-DNA[4]. Therefore, occult CMV infection can be considered a pathogenic factor in the occurrence of biliary complications. In this report, we describe the successful treatment of occult CMV cholangitis after pediatric LT which was achieved by isolating CMV-DNA from bile, which has not been reported previously.

A 7-mo-old baby girl who suffered from aggravated jaundice for 1 mo was admitted to our hospital.

The patient’s symptoms started 1 mo previously with no apparent cause. She had no fever, abdominal pain and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

She received a pediatric LT (donation after cardiac death) at another LT center in China due to bile acid (BA) and cholestasis cirrhosis on November 15, 2015. Her initial recovery went well and liver function returned to normal levels. On postoperative day (POD) 22, her liver function appeared abnormal for no apparent reason (Table 1). A liver biopsy was performed on POD 26. The results showed hydropic degeneration of the liver, local steatosis and cholestasis, suggesting that ischemia and drug-induced liver injury should be excluded. Moreover, abdominal ultrasound suggested that blood flow in the liver graft was normal with a small amount of effusion and no indication of bile duct dilatation. The doctors at that hospital suspected an acute rejection of her graft; therefore, she was treated with a pulse therapy of methylprednisolone and intravenous gamma globulin. However, she did not recover from aggravated jaundice and was transferred to our hospital.

| Date | POD 22 | POD 26 | POD 57 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 71.2 | 316.9 | 104.3 |

| AST (IU/L) | 69.7 | 331.7 | 244.8 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 131.2 | 261 | 376 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 242.1 | 969.8 | 1240.8 |

| TB (μmol/L) | 6.8 | 59.56 | 287.5 |

| DB (μmol/L) | 3.2 | 36.68 | 165.06 |

| BA (μmol/L) | 12.96 | 240.2 | 180.21 |

| Tacrolimus level (ng/mL) | 8.4 |

The patient’s temperature was 36.4°C, heart rate was 104 beats per min (bpm), respiratory rate was 30 breaths per min, and blood pressure was 91/53 mmHg. Her sclera and skin were severely yellow and no abdominal tenderness was observed.

Her liver function tests showed that alanine aminotransferase was 141 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase was 319 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was 482 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) was 1349 IU/L, total bilirubin (TB) was 263 μmol/L and direct bilirubin (DB) was 170 μmol/L. Albumin was normal, while cholesterol was 15.78 mmol/L and her tacrolimus trough level was 6.5 ng/mL. CMV-DNA in serum and urine were both negative.

Abdominal ultrasound showed intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography suggested an intrahepatic bile duct dilatation and biliary anastomotic stricture.

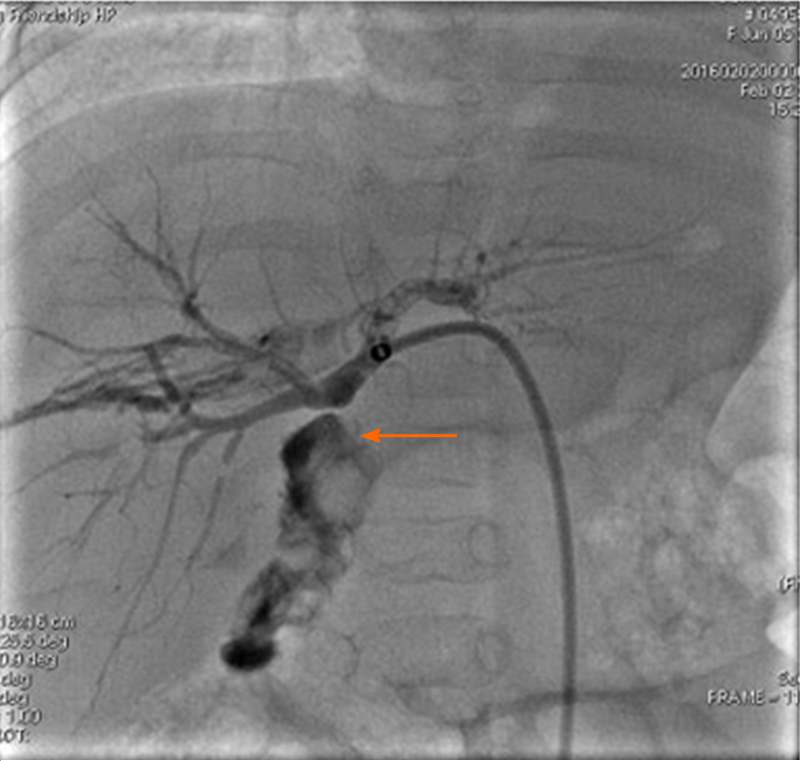

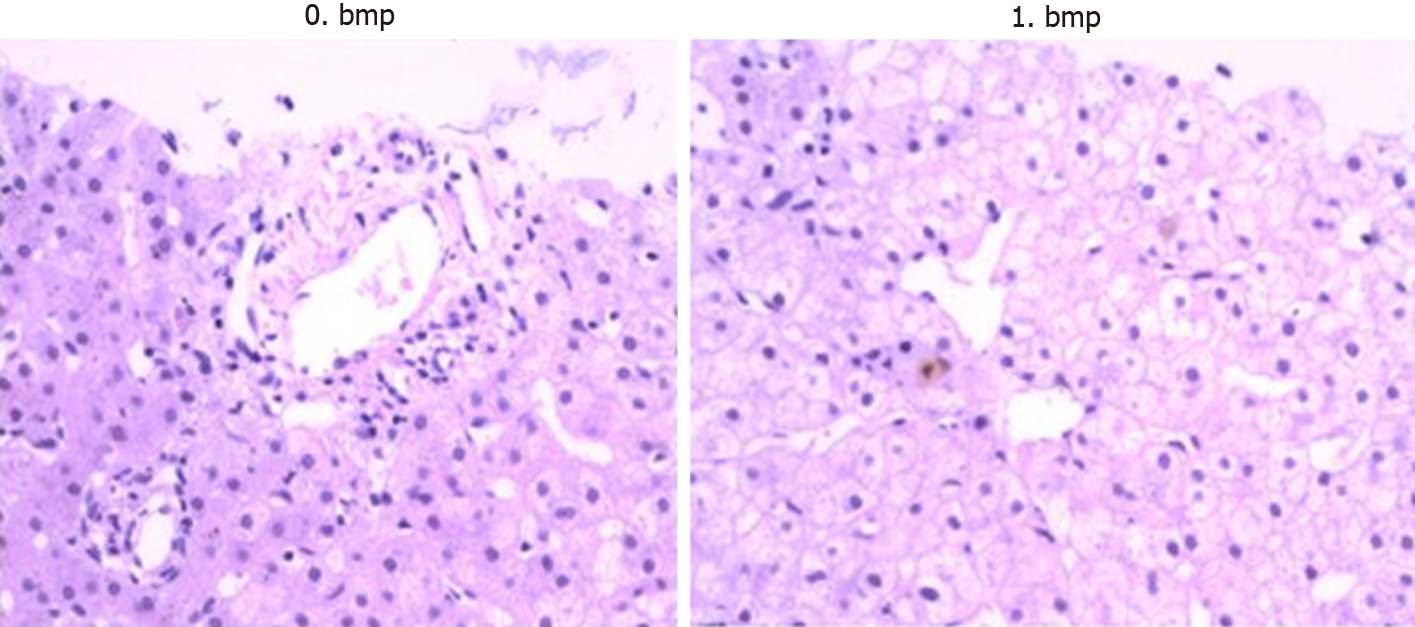

The patient was diagnosed with a biliary complication resulting in jaundice. Consequently, percutaneous transhepatic cholangio drainage (PTCD) was performed on POD 77. As biliary cholangiography revealed biliary anastomotic stricture, biliary drainage was completed after balloon dilatation (Figure 1). However, bile drainage volume was quite limited (about 10 mL/d) and its appearance was very pale. Her liver function did not improve after these treatments. TB increased from 200 to 240 μmol/L and DB increased from 130 to 160 μmol/L. Therefore, a liver biopsy was performed on POD 93. The results showed hydropic degeneration and cholestasis of the liver with negative CMV immunohistochemical stains (Figure 2).

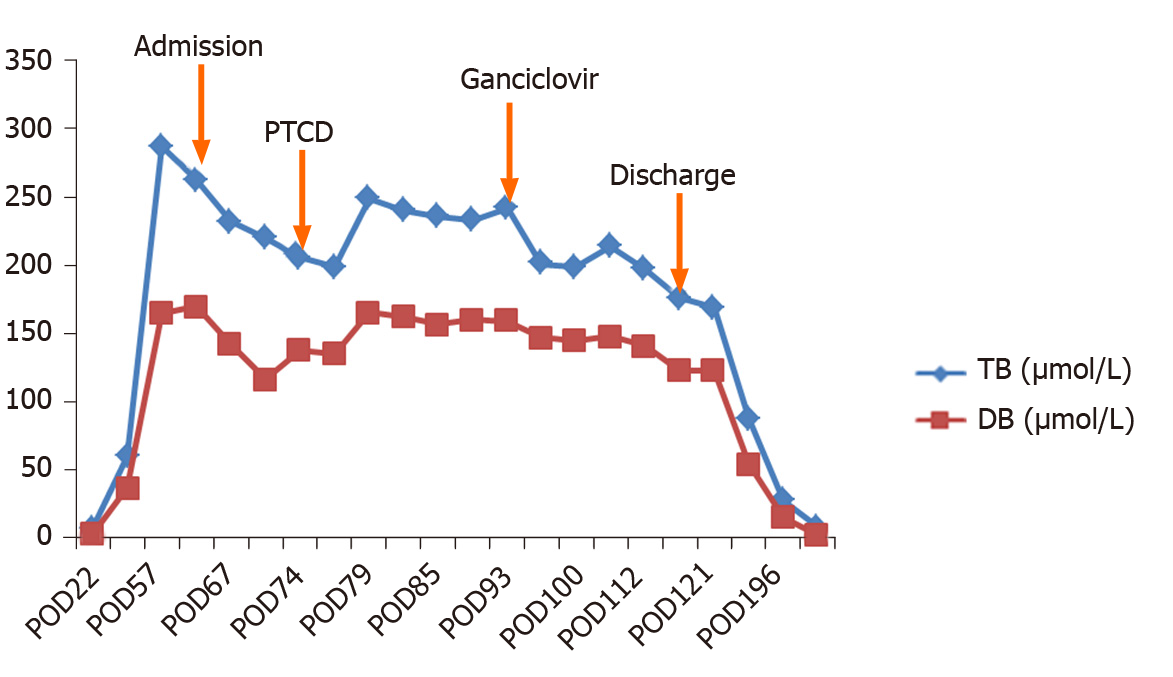

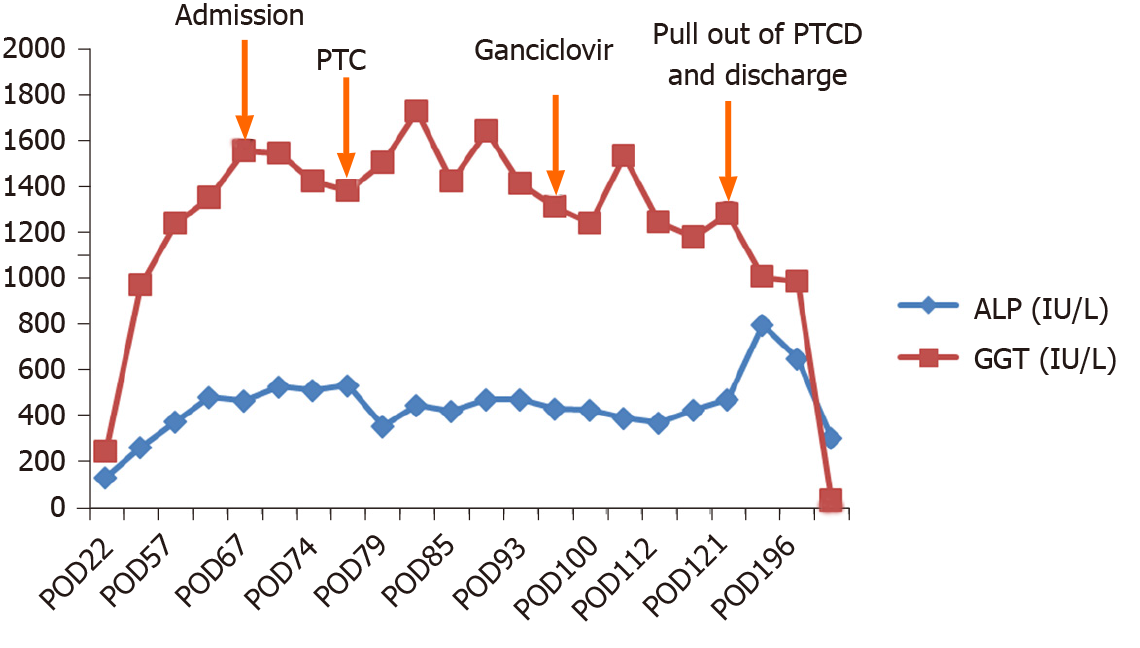

Although the serum CMV-DNA was negative, we collected a bile sample from PTCD drainage to test for CMV-DNA and unexpectedly found that bile CMV-DNA was 3 × 106 copies/mL. Accordingly, antiviral therapy with ganciclovir was administered at a dose of 10 mg/kg/d. After 2 wk of antiviral therapy, her bilirubin, ALP and GGT began to decline.

After 3-wk of treatment, bile CMV-DNA was tested again and was found to be negative. The child was then discharged after removal of her PTCD tube. Her TB, DB, ALP and GGT all gradually decreased to normal levels in August 2016 (Figures 3 and 4). During the 4-year follow-up period, her liver function has been normal.

Biliary complications represent a major problem accompanying LT, with an incidence of 10%-25%[5,6]. CMV infection in LT recipients has been associated with many complications and an increased risk of graft loss and death. Indirect complications of CMV include increased risk of hepatic allograft rejection and vanishing bile duct syndrome[7,8]. CMV produces inflammatory responses in the vascular endothelium and bile duct, which is related to chronic rejection and biliary complications that can occur after LT[9,10]. Although often treated prophylactically, CMV infection and CMV disease still remain a challenge, and continue to be a significant cause of morbidity, economic drain, and fatal disease.

Gotthardt reported that biliary CMV has been detected in LT recipients and was associated with non-anastomotic strictures[4]. Occult CMV infection may be associated with the occurrence of biliary complications. Gotthardt suggested that a noteworthy association may exist between occult biliary CMV infection and the development of non-anastomotic biliary complications in orthotopic LT patients.

Chronic CMV latency in bile duct epithelial cells may lead to chronic inflammation, and thus fibrosis of the bile duct system[9]. In our case, the patient’s primary disease was biliary atresia. CMV is considered to be a potential cause of the autoimmune destruction of the bile duct in biliary atresia[11]. In the study by Gotthardt et al[4], biliary CMV was more common in patients with a recipient-positive status. Therefore, biliary CMV was likely to be a reactivation and not an infection. The detection of pp65 antigen and CMV-DNA in serum lacks sensitivity[12,13]. Therefore, bile CMV sampling can be used for diagnosis, especially in patients with jaundice post-LT. As this was a case report, a larger sample size and multicenter investigation are needed in future studies.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the successful treatment of occult CMV cholangitis in a pediatric LT recipient. Our case suggests that detection of CMV in the bile and/or empirical treatment of CMV especially in patients with negative serum CMV-DNA and CMV pp65 may represent a potential option for the treatment of cholestasis post-LT and, in this way, decrease the risk of graft loss.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dinç T, Lambrecht NW S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Dubbeld J, van Hoek B, Ringers J, Metselaar H, Kazemier G, van den Berg A, Porte RJ. Biliary complications after liver transplantation from donation after cardiac death donors: an analysis of risk factors and long-term outcome from a single center. Ann Surg. 2015;261:e64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nemes B, Gámán G, Doros A. Biliary complications after liver transplantation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:447-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Aberg F, Mäkisalo H, Höckerstedt K, Isoniemi H. Infectious complications more than 1 year after liver transplantation: a 3-decade nationwide experience. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:287-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gotthardt DN, Senft J, Sauer P, Weiss KH, Flechtenmacher C, Eckerle I, Schaefer Y, Schirmacher P, Stremmel W, Schemmer P, Schnitzler P. Occult cytomegalovirus cholangitis as a potential cause of cholestatic complications after orthotopic liver transplantation? A study of cytomegalovirus DNA in bile. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1142-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moy BT, Birk JW. A Review on the Management of Biliary Complications after Orthotopic Liver Transplantation. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7:61-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Liu Y, Sun LY, Zhu ZJ, Wei L, Qu W, Zeng ZG. Bile microbiota: new insights into biliary complications in liver transplant recipients. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dogan N, Hüsing-Kabar A, Schmidt HH, Cicinnati VR, Beckebaum S, Kabar I. Acute allograft rejection in liver transplant recipients: Incidence, risk factors, treatment success, and impact on graft failure. J Int Med Res. 2018;46:3979-3990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Verma Y, Gupta E, Kumar N, Hasnain N, Bhadoria AS, Pamecha V, Khanna R. Earlier and higher rates of cytomegalovirus infection in pediatric liver transplant recipients as compared to adults: An observational study. J Lab Physicians. 2018;10:221-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Halme L, Hockerstedt K, Lautenschlager I. Cytomegalovirus infection and development of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:1853-1858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lattanzi B, Ott P, Rasmussen A, Kudsk KR, Merli M, Villadsen GE. Ischemic Damage Represents the Main Risk Factor for Biliary Stricture After Liver Transplantation: A Follow-Up Study in a Danish Population. In Vivo. 2018;32:1623-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Brindley SM, Lanham AM, Karrer FM, Tucker RM, Fontenot AP, Mack CL. Cytomegalovirus-specific T-cell reactivity in biliary atresia at the time of diagnosis is associated with deficits in regulatory T cells. Hepatology. 2012;55:1130-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jang EY, Park SY, Lee EJ, Song EH, Chong YP, Lee SO, Choi SH, Woo JH, Kim YS, Kim SH. Diagnostic performance of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigenemia assay in patients with CMV gastrointestinal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:e121-e124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Morinaga Y, Sawayama Y, Hidaka M, Mori S, Taguchi J, Takatsuki M, Eguchi S, Miyazaki Y, Yanagihara K. Diagnostic Utility of Cytomegalovirus Nucleic Acid Testing during Antigenemia-Guided Cytomegalovirus Monitoring after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation or Liver Transplantation. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2019;247:179-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |