Published online Jun 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2332

Peer-review started: March 5, 2020

First decision: March 24, 2020

Revised: April 9, 2020

Accepted: April 28, 2020

Article in press: April 28, 2020

Published online: June 6, 2020

Processing time: 94 Days and 12 Hours

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a common treatment for inoperable malignant renal tumors. However, a series of complications may follow the TACE treatment. Spinal cord injury caused by the embolization of intercostal or lumbar arteries is extremely rare.

We describe a case with quite uncommon spinal cord injury after TACE in a 3-year-old child with clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Sensory impairment beneath the T10 dermatomes and paraplegia on the day after TACE were found in this patient. Unfortunately, sustained paraplegia still existed for more than 2 mo after TACE despite the large dose of steroids and supportive therapy.

We should draw attention to an uncommon complication of paraplegia after TACE treatment in malignant renal tumors. Although it is rare, the result is disastrous.

Core tip: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization is a common treatment for inoperable malignant hepatic and renal tumors in adult patients, however, it is rarely applied in pediatric patients. A series of complications may follow the transcatheter arterial chemoembolization treatment. Spinal cord injury caused by the embolization of intercostal or lumbar arteries is extremely rare.

- Citation: Cai JB, He M, Wang FL, Xiong JN, Mao JQ, Guan ZH, Li LJ, Wang JH. Paraplegia after transcatheter artery chemoembolization in a child with clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(11): 2332-2338

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i11/2332.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2332

Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK), one of the malignant kidney neoplasms (2%-5% of primary kidney neoplasms in children), mostly occurs in children younger than 3 years old[1]. Compared to Wilms tumor, CCSK is more aggressive and poorly prognostic[2]. Once diagnosed, it is at an advanced stage and tends to metastasize to the bone and lung. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a relatively safe procedure applied in confining malignant tumors and treating unresectable hepatic cell carcinoma in adult patients. In the treatment of advanced Wilms tumor and CCSK, systemic chemotherapy combined with preoperative chemoembolization shows a better outcome than systemic chemotherapy[3]. The common complications of TACE are fever, bone marrow depression, vomiting, nausea, alopecia, and renal and hepatic failure. More serious complications have also been reported in untargeted embolism, such as tumor rupture, cholecystitis, splenic infarction, hepatic infarction, liver abscesses, and cerebral and pulmonary embolism[4]. Spinal cord injury rarely occurred after TACE, however, the outcomes are always disastrous, such as paraplegia. We present a case with paraplegia after TACE treatment of CCSK in a child via the right renal artery. To date, only four pieces of literature are reporting the embolic injury of the spinal cord in adult patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after TACE with iodized oil[5-8] (Table 1), however, no children cases have been presented. Here, we share our experience with spinal cord injury in a child with CCSK after TACE with a minireview of the literature.

| Ref. | Gender | Age (yr) | Cancer type | TACE (No.) | Selective artery | Sensory function | Motor function |

| Park et al[7] | M | 57 | HCC with rib metastasis | Several sessions | Right posterior intercostal artery | Improved fairly | Improved gradually |

| Bazine et al[5] | F | 62 | HCC | 1st | Hepatic artery | Improved completely | Unchanged |

| Tufail et al[8] | M | 45 | HCC | 2nd | Right hepatic artery | Improved markedly | Improved markedly |

| Kim et al[6] | M | 65 | HCC | 19th | Hepatic artery and intercostal arteries | Improved completely | Unchanged |

| M | 55 | HCC with rib metastasis | 6th | Improved gradually | Improved gradually | ||

| Our case | M | 3 | CCSK | 2nd | Right renal artery | Improved gradually | Unchanged |

A 3-year-old male child was diagnosed with CCSK approximately 1 mo prior by pathological examination after core needle aspiration biopsy. The child was admitted to our hospital because of CCSK for the 2nd TACE.

The patient’s symptoms were discovered one month prior and included abdominal distension without nausea, vomiting, fever, or hematuria. Core needle aspiration biopsy was carried out, and the pathological examination showed CCSK, a highly malignant renal tumor in children. TACE was performed after CCSK was diagnosed, along with a regimen of combined cisplatin (80 mg/m2), pirarubicin (40 mg/m2), vindesine (3 mg/m2), and lipiodol (5 mL). The adverse effects of this procedure were unremarkable except several days of mild fever, which was self-limited.

The patient had no previous medical history.

The patient had no remarkable medical or family history.

Vital signs were as follows: Blood pressure of 96/52 mmHg, heart rate of 116 per minute, respiratory rate of 28 per minute, and body temperature of 36.7 °C. Except for a mass in the right upper abdomen, his physical examination was not remarkable. His blood pressure and heart rate were normal. He had no abnormal neurological symptoms or signs.

Routine laboratory tests revealed no obvious elevation in the values of blood tumor markers.

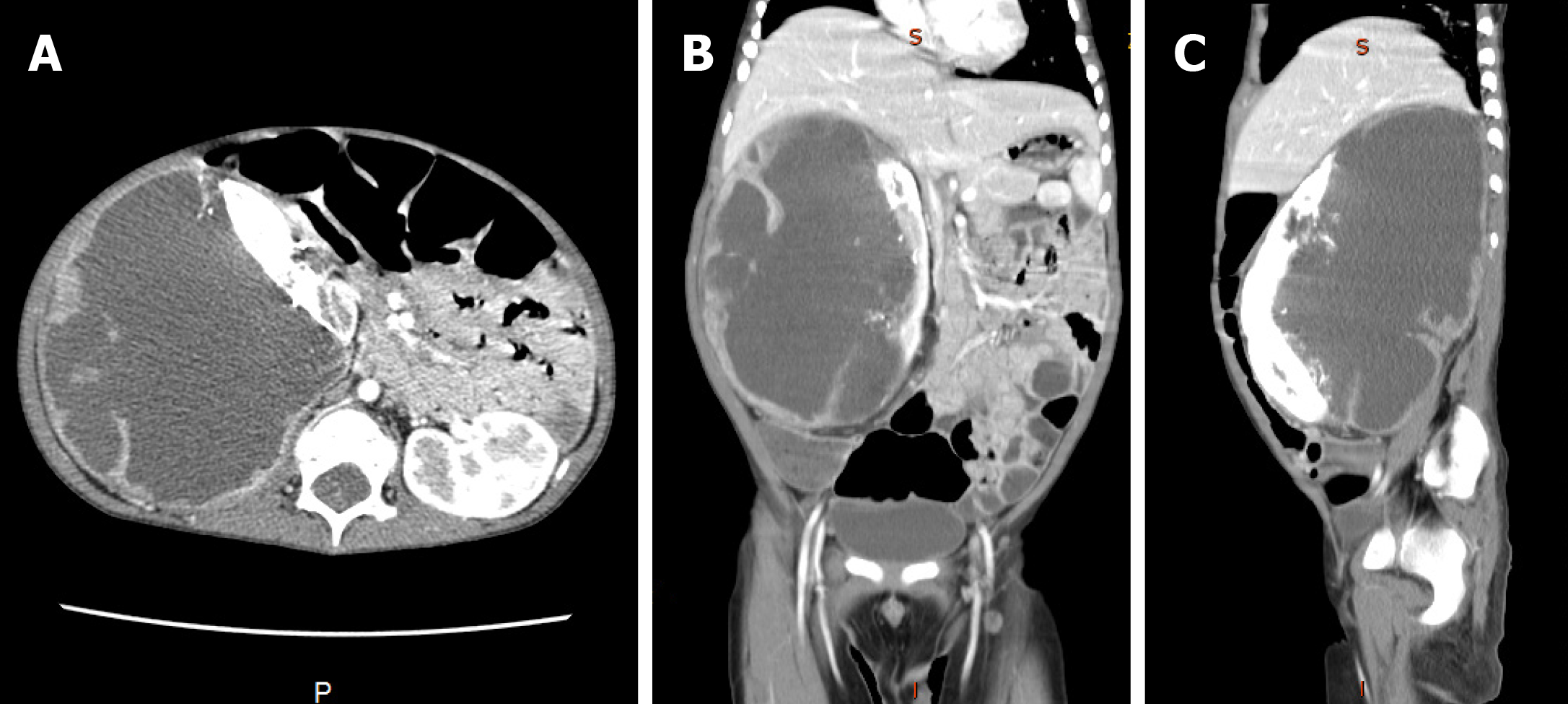

An abdominal enhanced computed tomography scan showed a mass (95 mm × 110 mm × 160 mm) in the right kidney which was slightly enhanced in the dynamic phase (Figure 1).

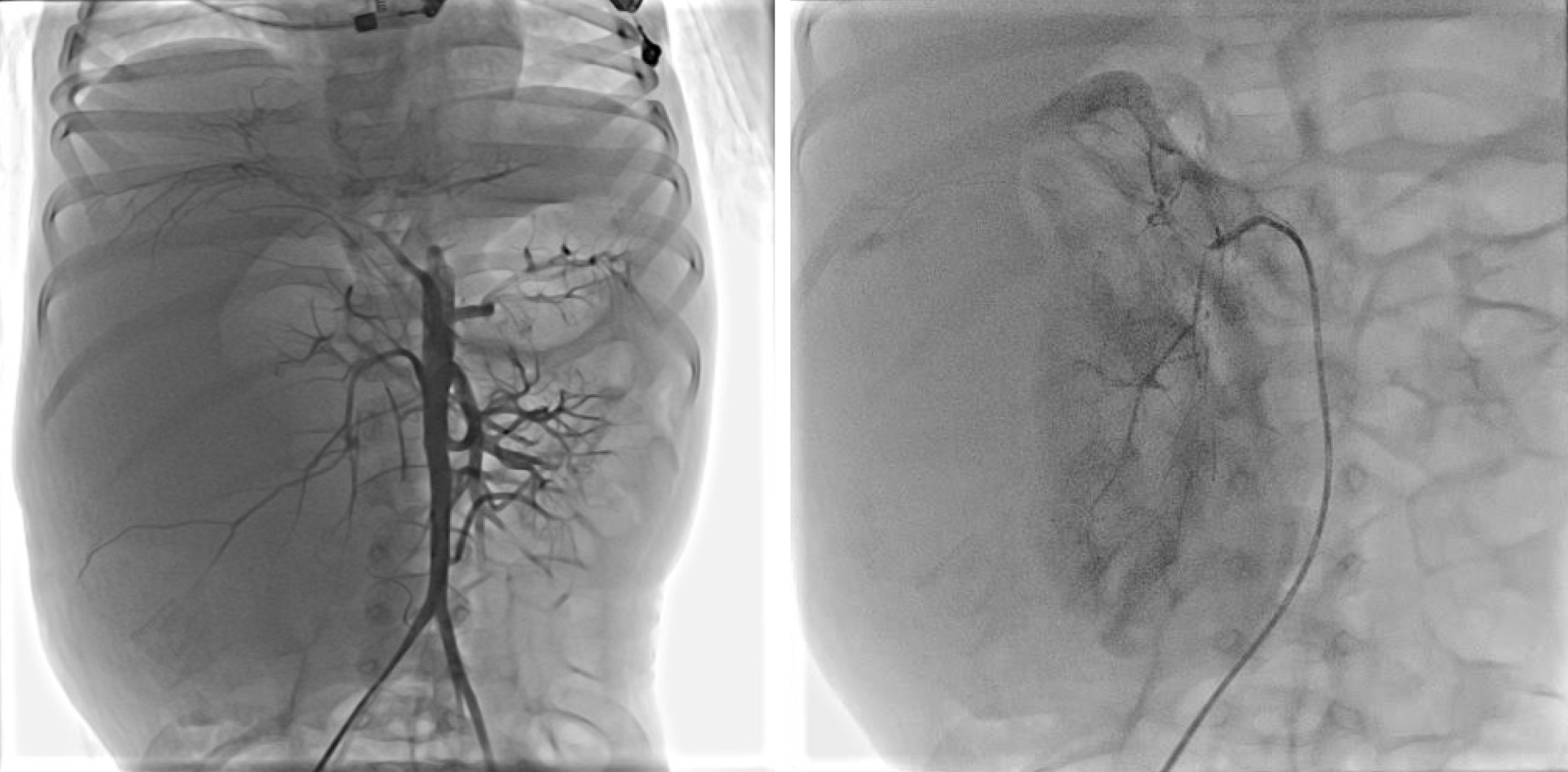

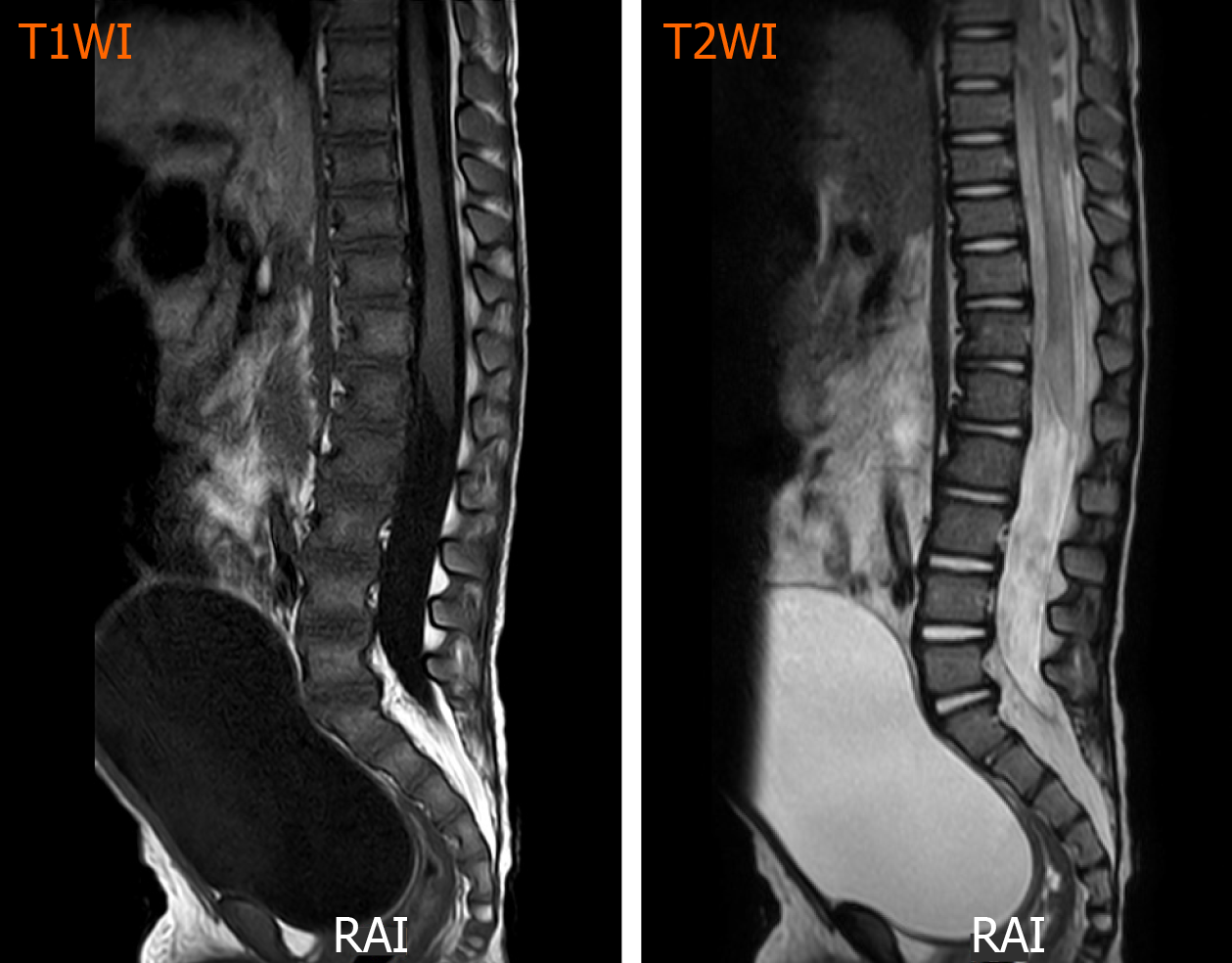

One day after admission, under general anesthesia, the patient received the 2nd TACE (Figure 2) of combined pirarubicin (40 mg/m2), cisplatin (80 mg/m2), vindesine (3 mg/m2), and 5 mL of iodized oil with gelfoam via the right renal artery. The patient experienced sudden paraplegia and loss of the somatosensory in the trunk under the level of the sternum and both lower extremities together with urinary retention and dyschezia after TACE. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spinal cord showed that the signal intensity of L1-L5 was increased in T2 weighted images (Figure 3).

Based on the results of tumor biopsy, the diagnosis was CCSK and spinal cord injury resulting in paraplegia after TACE.

The patient was treated with a consecutive high dose of methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg/d, iv) for 5 d and mecobalamin (0.5 mg, PO, QD), and rehabilitation activity.

The patient continued to suffer from paraplegia with urinary retention and dyschezia for more than 2 mo after TACE. His sensory impairment and voiding sensation gradually improved, but the motor strength did not recover at all.

TACE is a procedure widely applied for unresectable hepatic cell carcinoma in adult patients and significantly improves the evolution of interventional oncology therapy[9]. The combination of systemic chemotherapy and TACE in the context of pediatric renal malignancy can lead to massive tumor necrosis, clear up distant metastasis, improve the complete tumor resection rate, and obtain an excellent survival rate[3,10]. TACE has been reported to be associated with postembolization syndrome, such as pain, fever, nausea, fatigue, and elevated transaminases, which are usually self-limited[11]. The incidence of untargeted organ embolization, such as pulmonary oil embolism, splenic infarction, and gallbladder infarction, was found to be 4.6%[12]. Rare neurological complications associated with TACE, usually occur as a result of lipiodol embolism in the central nervous system[13]. Focal symptoms appear in the distribution area of the affected vessels, which can be confirmed by imaging studies. Spinal cord injury is quite uncommon after TACE.

The spinal cord blood is mainly supplied by one anterior and two posterior spinal arteries that originate from the vertebral artery, providing blood to the 3/4 anterior and 1/4 posterior region of the spinal cord, respectively. The anterior spinal artery coincides with the anterior spinal artery of the carotid, intercostal, and lumbar arteries[14]. The left and right posterior spinal arteries are connected with the posterior radicular arteries, which also originate from the cervical artery, the posterior intercostal artery, and the spinal branches of the lumbar artery. Therefore, when the anterior spinal artery is embolized, the main ischemic injury occurs in the anterior 3/4 part of the spinal cord, including the anterior and lateral funiculus. Dysfunction mainly affects the motor system rather than the sensory system, which is more serious[7]. On the contrary, the ischemic injury in the posterior 1/4 area of the spinal cord is more likely to cause sensory impairment than motor dysfunction, and the symptoms are much milder than anterior spinal artery syndrome.

To date, there have been few reported cases of paraplegia after TACE performed via the phrenic artery or intercostal artery in adult hepatocellular carcinoma patients. In some cases, sensory dysfunction improves rapidly, but motor disorders do not fully recover, even for a few months. This reminds us that spinal cord injury is caused by anterior spinal artery infarction. On the contrary, during the intercostal artery or lumbar artery angiography, the posterior spinal artery was injured, and the sensory and motor functions of the patients recovered completely 2 mo later.

In these reported cases, collateral recanalization due to hepatic artery injury or previous reduction of TACE site blood flow resulted in neurological complications after TACE, which often occurred after the second or third treatment[15]. Few cases have been reported after renal artery embolization. Our patient had previously received TACE treatment of the right renal artery without any serious complications. The second TACE involved the right lumbar artery, which provides a partial blood supply to the tumor, and led to the complication. Due to arterial obstruction caused by arterial injury, through recurrence and recruitment to the spinal cord, lipiodol led to ischemia of the spinal cord. Our patient developed both lower extremity defects after surgery, which is related to numbness, retention of urine, and dyschezia. All of these symptoms can be attributed to lumbar spinal cord ischemia in the L1-L4 region. The sensory disturbance gradually recovered, but the motor dysfunction did not fully recover, even 2 mo after the injury. This suggests that spinal cord injury is caused by anterior spinal artery infarction.

Therefore, a clear understanding of the details of the target artery and adjacent arteries before the TACE procedure is very important. Enhanced computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography must be performed preoperatively. Cone beam computed tomography and three-dimensional (3D) digital rotational angiography were also applied during the digital subtraction angiography procedure in some reports[16-20], and they can show clear artery details in 3D; thus, the arteries can be seen from appropriate angles, which can decrease the operation time, arterial injuries, and complications after the operation. Therefore, in complex cases with complex vascular anatomy, the use of 3D rotational angiography is helpful to reduce the risk of surgery or complications, and lead to a more effective focus location. Moreover, due to artery obstruction, the flow of lipiodol into unintended arteries will increase with high pressure. Applying 3D digital rotational angiography to TACE and using low pressure to infuse lipiodol will facilitate the procedure, make it convenient and fast to select the intended artery, and decrease the rate of poorly selecting arteries and the relevant complications caused by unintentional chemoembolization; additionally, this approach can decrease the rate of non-target organ infarction.

Spinal cord injury is a rare but serious complication after renal TACE. We should draw attention to the rare complication of paraplegia after TACE treatment in malignant renal tumors. Although it is rare, the result is disastrous.

The authors thank the child and his parents for allowing us to publish the data collected. The authors also thank the staff of the Department of Radiology, and Pathology for their cooperation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aramini B, Gonoi W, Khoury T S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Gooskens SL, Furtwä:ngler R, Vujanic GM, Dome JS, Graf N, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: a review. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2219-2226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Green DM, Breslow NE, Beckwith JB, Moksness J, Finklestein JZ, D'Angio GJ. Treatment of children with clear-cell sarcoma of the kidney: a report from the National Wilms' Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2132-2137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang JH, Li MJ, Tang DX, Xu S, Mao JQ, Cai JB, He M, Shu Q, Lai C. Neoadjuvant transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and systemic chemotherapy for treatment of clear cell sarcoma of the kidney in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:550-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, Senzolo M, Cholongitas E, Davies N, Tibballs J, Meyer T, Patch DW, Burroughs AK. Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:6-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in RCA: 616] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bazine A, Fetohi M, Berri MA, Essaadi I, Elbakraoui K, Ichou M, Errihani H. Spinal cord ischemia secondary to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2014;8:264-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim JH, Yeon JE, Jong YK, Seo WK, Cha IH, Seo TS, Park JJ, Kim JS, Bak YT, Byun KS. Spinal cord injury subsequent to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Park SJ, Kim CH, Kim JD, Um SH, Yim SY, Seo MH, Lee DI, Kang JH, Keum B, Kim YS. Spinal cord injury after conducting transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for costal metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012;18:316-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tufail K, Araya V, Azhar A, Hertzog D, Khanmoradi K, Ortiz J. Paraparesis caused by transarterial chemoembolization: A case report. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:289-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liapi E, Georgiades CC, Hong K, Geschwind JF. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: current technique and future promise. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;10:2-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li MJ, Tang DX, Xu S, Huang Y, Wu DH, Wang JH, Lai C, Tang HF, Shu Q, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Neoadjuvant Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization and Systemic Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Wilms Tumor. In: van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM1, editor. Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications, 2016. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Blackburn H, West S. Management of Postembolization Syndrome Following Hepatic Transarterial Chemoembolization for Primary or Metastatic Liver Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:E1-E18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Tarazov PG, Polysalov VN, Prozorovskij KV, Grishchenkova IV, Rozengauz EV. Ischemic complications of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in liver malignancies. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:156-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Choi CS, Kim KH, Seo GS, Cho EY, Oh HJ, Choi SC, Kim TH, Kim HC, Roh BS. Cerebral and pulmonary embolisms after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4834-4837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bolton B. THE BLOOD SUPPLY OF THE HUMAN SPINAL CORD. J Neurol Psychiatry. 1939;2:137-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Lee KH, Sung KB, Lee DY, Park SJ, Kim KW, Yu JS. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: anatomic and hemodynamic considerations in the hepatic artery and portal vein. Radiographics. 2002;22:1077-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ambrosini P, Ruijters D, Niessen WJ, Moelker A, van Walsum T. Continuous roadmapping in liver TACE procedures using 2D-3D catheter-based registration. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2015;10:1357-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kakeda S, Korogi Y, Hatakeyama Y, Ohnari N, Oda N, Nishino K, Miyamoto W. The usefulness of three-dimensional angiography with a flat panel detector of direct conversion type in a transcatheter arterial chemoembolization procedure for hepatocellular carcinoma: initial experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:281-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Minami Y, Yagyu Y, Murakami T, Kudo M. Tracking Navigation Imaging of Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Three-Dimensional Cone-Beam CT Angiography. Liver Cancer. 2014;3:53-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pung L, Ahmad M, Mueller K, Rosenberg J, Stave C, Hwang GL, Shah R, Kothary N. The Role of Cone-Beam CT in Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:334-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang Z, Chapiro J, Schernthaner R, Duran R, Chen R, Geschwind JF, Lin M. Multimodality 3D Tumor Segmentation in HCC Patients Treated with TACE. Acad Radiol. 2015;22:840-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |