Published online Jun 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2235

Peer-review started: March 12, 2020

First decision: April 25, 2020

Revised: May 4, 2020

Accepted: May 26, 2020

Article in press: May 26, 2020

Published online: June 6, 2020

Processing time: 87 Days and 6.8 Hours

The most important factors affecting attitudes on organ donation are socioeconomic, educational, cultural, and religious factors in many countries.

To evaluate the attitudes, awareness, and knowledge levels of the Turkish adult population toward organ donation.

This nationwide study surveyed 3000 adults (≥ 18 years) in Turkey. To ensure a representative sample, the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics-II (modified for Turkey) was used. Turkey was divided into 26 regions based on social, economic, and geographic criteria as identified by the Turkish Statistical Institute. A stratified sampling method was used with an even distribution of adults across cities and towns based on population data. Data were collected by the PRP Research and Consultancy Company using computer-assisted personal interviews.

Out of 3000 individuals represented in the study population, 1465 (48.8%) were male and 1535 (51.2%) female. The results showed that most participants were under 45 years (59.0%) and married (72.1%), some had a bachelor's degree or higher (21.9%), and very few (1.5%) had any direct experience with organ transplantation - whether in the family, or a family member on a transplantation waiting list. Most of the study population (88.3%) had not considered donating an organ, however, most (87.9%) said that they would accept an organ from a donor if they needed one. Among the individuals surveyed, 67% were willing to donate an organ to a close relative, while 26.8% would donate an organ to an unrelated person. Only 47.2% said they had adequate information about brain death, and 85.2% refused to consent to donating organs of family members declared brain dead. Only 33.9% thought they had adequate information about organ donation. The main source of information was the television. The two main reasons for refusing organ donation were that it was too soon to think about organ donation and the importance of retaining the integrity of the dead person’s body.

This study showed that Turkey’s adult population has inadequate knowledge about organ donation. The study advocates for public education programs to increase awareness among the general population about legislation related to organ donation.

Core tip: The small pool of transplant organs remains a major problem especially in Asia and the Middle East. The most important factors affecting the availability of organs are socioeconomic, educational, cultural, and religious. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the attitudes, awareness, and knowledge levels of Turkish adults toward organ donation.

- Citation: Akbulut S, Ozer A, Gokce A, Demyati K, Saritas H, Yilmaz S. Attitudes, awareness, and knowledge levels of the Turkish adult population toward organ donation: Study of a nationwide survey. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(11): 2235-2245

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i11/2235.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2235

There is an overwhelming disparity between the need for transplant organs and the shortage of donor organs. In Turkey, as in the rest of the world, the major barrier to transplantation is the shortage of donor organs. The organ donation rate in Turkey is lower than in Western countries. Donation rates per million of the population vary between countries: Turkey (7.0), South Korea (11.4), Sweden (20.3), United Kingdom (21.2), United States (30.7), Portugal (32.6), and Spain (43.6)[1].

Public awareness of organ donation is directly correlated to levels of education[2,3]. In order to develop effective public policies to promote organ donation, it is important to understand the public’s viewpoints on this issue in order to identify target groups and to determine how to approach them effectively.

Research indicates that knowledge about organ procurement is positively correlated with signing an organ-donor card[2,3]. The decision to donate organs can be difficult for individuals who are not adequately informed about organ donation. Some individuals may already have made up their minds about registering as an organ donor, while others may be in doubt for a variety of reasons. These two groups require different approaches in terms of raising awareness and knowledge, and incentivizing registration.

To improve organ supply, continued efforts and strategic planning are required. The general public’s awareness plays an important role in increasing the pool of organ donors. Several studies have investigated people’s attitudes toward organ donation and their willingness to register as organ donors, and focused on socio-demographic differences in attitudes, knowledge, and behavior[2]. Little is known about the Turkish population’s attitudes and knowledge. The aim of this study was to evaluate the knowledge and perception of people in Turkey toward organ donation as well as to identify the reasons and determinants for refusing organ donation. Insight from this study could help determine strategies for policy-makers and highlight issues that can lead to a change in attitude and behavior, and promote organ donation and reduce the organ shortage in Turkey.

This study aimed to evaluate the awareness, attitudes, and knowledge levels of Turkish adults toward organ donation through a national survey. To achieve this goal, individual’s ≥ 18 years of age, the minimum age at which a person is able to give consent to donate their organs, were included in this study. Creative Survey Systems’ Sample Size Calculator was used to establish the minimum sample size (http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm), which was calculated as 2997 (confidence level: 95%, confidence interval: 1.79, population: Approximately 3 million adult people) and revised to 3000. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Inonu University Institutional Review Board for Non-Interventional Studies (2017/24-7). The study was supported and funded by the Inonu University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (Project No: 2018/976).

The Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS-II), developed by Statistical Office of the European Union (EuroStat) and modified for Turkey, was used to represent the general adult population of Turkey. Turkey was divided into 26 regions based on similarities in social demographics, economy, and geography as identified by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) using the NUTS-II system. A total of 3000 adult individuals, distributed over 26 cities and equally between city centers and towns based on relative population densities, were identified. The national survey was conducted by PRP Research and Consultancy Company located in Istanbul. A survey protocol was laid out with the company. The preparation of the survey, including the selection of pollsters and the reporting of results, was conducted in accordance with ISO 9001/ISO 20252 and Esomar. A stratified sampling method that included age, sex, education levels, and marital status was used for this survey study. Participants were given a form called “The awareness of the general population about organ donation,” which included 32 questions. The survey was conducted using computer-assisted personal interviewing.

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The categorical variables were presented as both a number and percentage (%).

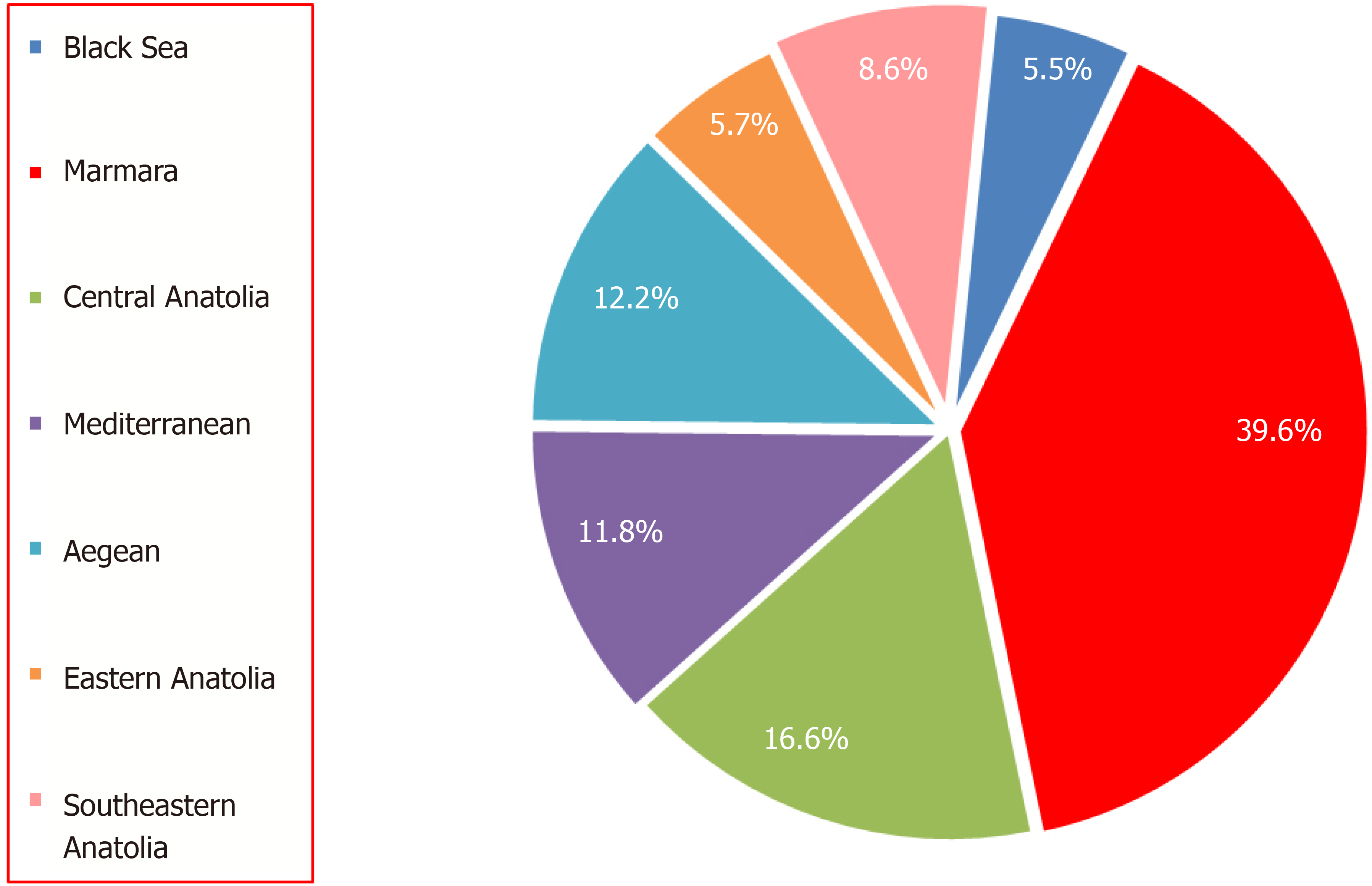

A total of 3000 adult individuals, representative of the Turkey adult population, were included in the sample, of whom 1465 (48.8%) were male and 1535 (51.2%) female; 59.0% were younger than 45 years, 66.8% were less than 174 cm in height, and 50.2% weighed less than 75 kg. A total of 2248 (74.9%) individuals were married, and 85 (2.8%) individuals were divorced - the divorce rate among married individuals was 3.78%. Among those included in the survey, 16.8% had a primary school education, 36.0% had completed high school, 20.7% had a bachelor’s degree, and 1.2% had completed a master’s degree or a doctorate. The ranking of the participants by occupation was as follows: Private sector (34.1%), housewife (19.1%), retired (10.8%), public sector (10.4%), tradesman (9.5%), unemployed (6.8%), student (6.2%), other (2.0%), and farmer (0.9%) (Table 1). The geographic distribution of the individuals according to their place of birth was as follows: Marmara (39.6%), Central Anatolia (16.6%), Aegean (12.2%), Mediterranean (11.8%), Southeastern Anatolia (8.6%), Eastern Anatolia (5.7%), and Black Sea (5.5%) (Figure 1).

| Demographic features | n (%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 1465 (48.8) |

| Female | 1535 (51.2) |

| Age (yr) | |

| 18-34 | 1065 (35.5) |

| 35-44 | 705 (23.5) |

| 45-54 | 548 (18.3) |

| ≥ 55 | 682 (22.7) |

| Marrital status | |

| Married | 2163 (72.1) |

| Unmarried | 752 (25.1) |

| Divorced | 85 (2.8) |

| Educational level | |

| Unschooled | 194 (6.6) |

| Primary school | 504 (16.8) |

| Secondary school | 271 (9.0) |

| High school | 1079 (36.0) |

| Associate’s degree | 292 (9.7) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 622 (20.7) |

| Master’s degree | 24 (0.8) |

| Doctorate degree | 11 (0.4) |

| Career | |

| Employed (private sector) | 1025 (34.1) |

| Housewife | 574 (19.1) |

| Retired | 324 (10.8) |

| Employed (public sector) | 313 (10.4) |

| Tradesman | 286 (9.5) |

| Unemployed | 205 (6.8) |

| Students | 187 (6.2) |

| Lawyer, architect, engineer, doctor | 59 (2.0) |

| Farmer | 27 (0.9) |

| Monthly income | |

| ≤ 2000 TL | 597 (19.9) |

| 2000-4000 TL | 1734 (57.8) |

| 4000-5000 TL | 243 (8.1) |

| ≥ 5000 TL | 304 (10.1) |

| No response | 122 (4.1) |

Of the 3000 individual included in the survey, 0.7% (n = 22) said that they have donated their organs; 88.3% (n = 2629) said that they would not, and 6.8% (n = 203) said that they were undecided. The study also found that 28.5% (n = 846) responded that “it is too soon for me to decide on organ donation”, 17.9% (n = 533) said that they were concerned about body deterioration, 17.5% (n = 519) indicated that they had no specific reason for not donating their organs, 11.5% (n = 343) said that they were concerned about their organs being harvested before they were declared brain dead, and 8.6% (n = 257) said that they did not want to donate due to religious beliefs.

Among the study population, 36.7% (n = 1101) said they had no information about organ donation, and 33.9% (n = 1017) said they had enough information regarding organ donation. Sources of information included television programs 15.3% (n = 428), the internet 10.2% (n = 286), and healthcare professionals 13.7% (n = 383).

Among the study population, 1.1% (n = 33) said their relatives were on an organ waiting list; 1.4% (n = 42) said a relative had received an organ transplant; 28.4% (n = 851) said that a living donor transplantation was the best option; and 36.9% (n = 1107) said that cadaveric organ donation was the best source for organ transplantation (Table 2).

| Organ donation information | n (%) |

| Have you donated your organs? | |

| Yes | 22 (0.7) |

| No | 2978 (99.3) |

| Are you willing to donate your organs in future? | |

| Yes | 146 (4.9) |

| No | 2629 (88.3) |

| Undecided | 203 (6.8) |

| Do you have any relatives on transplantation waiting list? | |

| Yes | 33 (1.1) |

| No | 2905 (96.8) |

| No idea/No sure | 62 (2.1) |

| Did any of your relatives have organ transplantation? | |

| Yes | 42 (1.4) |

| No | 2895 (96.5) |

| No idea/No sure | 63 (2.1) |

| Would you accept organ transplantation if it is necessary? | |

| Yes | 2637 (87.9) |

| No | 124 (4.1) |

| No idea/No sure | 239 (8.0) |

| Do you think you have adequate information on brain death? | |

| Yes | 1415 (47.2) |

| No | 867 (28.9) |

| No idea/No sure | 718 (23.9) |

| Do you think that a patient with brain death may recover? | |

| Yes | 335 (11.2) |

| No | 1979 (66.0) |

| No idea/No sure | 686 (22.8) |

| Would you give consent to organ donation of the relatives? | |

| Yes | 225 (7.5) |

| No | 2555 (85.2) |

| No idea/No sure | 220 (7.3) |

| Do you think that it is appropriate to use homeless people organs after death? | |

| Yes | 1406 (46.8) |

| No | 1090 (36.3) |

| No idea/No sure | 504 (16.8) |

| Are you willing to donate your organs to unrelated people when necessary? | |

| Yes | 804 (26.8) |

| No | 1281 (42.7) |

| No idea/No sure | 915 (30.5) |

| Are you willing to donate your organs to close relatives when necessary? | |

| Yes | 2010 (67.0) |

| No | 375 (12.5) |

| No idea/No sure | 615 (20.5) |

| Is it important for you to whom your organs will be transplanted if you donate it? | |

| Yes | 1066 (35.5) |

| No | 1715 (57.2) |

| No idea/No sure | 219 (7.3) |

| Do you have adequate information about organ donation? | |

| Yes | 1017 (33.9) |

| No | 1101 (36.7) |

| No idea/No sure | 882 (29.4) |

| Do religion leaders views affect your donation perspective? | |

| Yes | 890 (29.6) |

| Partially | 413 (13.8) |

| No | 1697 (56.6) |

| Do opinion leaders' views affect your decision to donate organs? | |

| Yes | 745 (24.9) |

| Partially | 421 (14.0) |

| No | 1834 (61.1) |

| Which is the most ideal type of organ transplantation? | |

| Living donor (family member, relatives, non-related, etc.) | 851 (28.4) |

| Deceased donor | 1107 (36.9) |

| No idea/No sure | 1042 (34.7) |

| What are your reasons to refuse organ donation? | |

| It's too early for me to think about organ donation | 846 (28.5) |

| Body integrity can deteriorated after death | 533 (17.9) |

| My organs can be harvested before brain death | 343 (11.5) |

| Familial and social causes | 286 (9.6) |

| My organs might use for commercial purposes | 262 (8.8) |

| Religious beliefs | 257 (8.6) |

| My organs might get into the hands of the mafia | 213 (7.2) |

| I have never considered organ donation | 181 (6.1) |

| Health problems | 155 (5.2) |

| Distrust against health institutions | 158 (5.3) |

| Organ allocation system is not equitable | 132 (4.4) |

| No enough knowledge about organ donation | 29 (0.9) |

| No specific reason | 519 (17.5) |

| Which are the most effective methods for raising awareness of organ donation? | |

| Seminars and organization of campaigns for organ donation in schools | 1941 (64.7) |

| Organization of campaigns for donation in all official institutions Financial support by the government to organ donors | 1680 (56.0) |

| Financial support by the government to organ donors | 987 (32.9) |

| Improving the knowledge of the healthcare workers regarding brain death and donation | 812 (27.1) |

| Giving priority to organ donors when necessary | 558 (18.6) |

| Tax discount to individuals agreeing in organ donation | 550 (18.3) |

| Media support for promotion of organ donation | 108 (3.6) |

| Organization of periodic educational seminars | 64 (2.1) |

| Preaching by religious officials about the necessity of organ donation | 30 (1.0) |

| What are your main sources of information on organ donation? | |

| Television programs | 428 (15.3) |

| Daily newspaper | 191 (6.8) |

| Internet platform | 286 (10.2) |

| Healthcare professionals | 383 (13.7) |

| Social media (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Twitter, etc.) | 175 (6.3) |

| During education | 115 (4.2) |

| Books/magazines/radio | 72 (2.6) |

| Other | 106 (3.8) |

Among the study population, 67% (n = 2010) said they would donate an organ if a close relative needed an organ transplant, while 20.5% (n = 615) said that it was a difficult decision to make. On the other hand, 26.8% (n = 804) of the study population said that they would donate an organ if an unrelated people needed one; and 87.9% (n = 2637) said that they would consent to organ donation if they suffered organ failure.

Among the study population, 47.2% (n = 1415) said they had enough information about brain death; 66% (n = 1979) said they did not believe that a patient who was brain dead could recover; 85.2% (n = 2555) said they would not allow the donation of organs of a relative if they were declared brain dead. Among the study population, 43.4% (n = 1303) said the views of religious leaders on organ donation totally or partially influenced their own views; and 38.9% (n = 1166) said the views of opinion leaders on organ donation totally or partially influenced their own views. Interestingly, 35.5% (n = 1066) of the individuals said it was important for them to know the recipient of the transplanted organs (Table 2).

Organ transplantation has become the gold standard treatment option for patients with end-stage organ failure[4,5]. However, there is an overwhelming disparity between the need for organ transplants and the worldwide shortage of donor organs[6,7]. Many patients die while on the waiting list due to the long waiting period, or become too sick for the transplant to be performed and get dropped from the list. To offset the organ shortage, living donation is being encouraged. Countries in Asia and the Middle East are expected to take the lead in living donor organ transplantation (LDLT)[8,9]. According to the records of the Turkish Ministry of Health, in 2015 an estimated 935 patients per million of the population had kidney failure, but only 17.4% received transplants. Most of the patients (77.3%) received hemodialysis treatment[7]. Due to the limited supply of livers, there are thousands of candidates waiting for liver transplants in Turkey - less than 30% received organ donations in 2017[10]. LDLT has a high risk of morbidity and mortality for donors and therefore, even if there is an organ shortage in Western countries, they prefer not to perform LDLT. There is a general agreement that cadaveric organ donation should be promoted in order to address both organ shortages and also to prevent healthy donors from the risks associated with organ donation.

In any health system, public awareness of organ donation fundamentally affects the organ transplantation program: knowledge and perceptions about organ donation are positively associated with attitudes to donation, willingness to donate, and donor registration[2,3]. In this study while most individuals in the study population (88.3%) said they would not consider donating an organ, most (87.9%) said they would accept an organ from a donor if they needed one. The data revealed the complexity of individuals' attitudes toward donation and the need for more sophisticated future studies on the interactions between the broader factors influencing donation. Possible explanations for the ambivalent attitude highlighted in this study include poor knowledge (most of study population thought they do not have enough information on organ donation) and no knowledge (36.7% said they had no information) on the topic. Furthermore, many said they had never thought about organ donation and it was too soon for them to consider organ donation. In addition, 17.9% were concerned about body deterioration and disfigurement after death; 17.5% had no specific reason for their point of view, and 8.6% said they would not donate due to religious beliefs. Other reasons included family suffering, social causes, concerns about organ handling and organ trafficking, mistrust in the health institution, and the organ allocation system.

In this study, gender had no major effect on the willingness to donate organs. In another study, gender had no major effect on attitudes toward organ donation despite inadequate levels of knowledge among females[11]. However, a review based on 33 studies showed that among female respondents, experiential knowledge about organ donation and their families’ positive attitudes were found to be the most influencing factor for organ donation, in addition to younger age, higher socioeconomic status, education, and knowledge and awareness of organ donation[3].

Studies showed that the most important factors detected in this survey, which also featured in the multivariate analysis, are mainly related to three aspects: The family, manipulation of the body, and religion[12]. At the family level, it has been shown that talking about the matter in family circles increased the chances of being in favor of organ donation[13,14]. In this context, the attitude of a respondent's partner toward donation was fundamental[14]. In this study, while most of the study population (88.3%) would not consider donating an organ, 67% showed a willingness to donate an organ if a close relative needed an organ transplant, while only 26.8% said they would donate an organ to an unrelated person. This confirms the effect of family on organ donation attitude. The critical role of the family in organ donation decision-making has been confirmed in many studies.

A study on organ donation related knowledge, attitude, and willingness to donate organs among a group of university students in Western China reported that the Chinese family plays a critical role in organ donation decision-making. Most respondents not only tended to value the opinions of their family members, they also preferred to donate their organs to their family members or friends rather than strangers[15]. These results were consistent with our results and with results of studies conducted in other countries such as Palestine, Turkey, Spain, and Poland[10,16,17]. These results also suggest that the support of family members is very important for a potential donor in motivating and upholding their willingness in organ donation.

Another important independent variable related to a more negative attitude toward organ donation is manipulation of the body, and poor understanding of the concept of brain death, a factor classically related to attitude toward donation[18,19]. In this study 66% of the study population did not believe that a patient with brain death could recover; however, the majority (85.2%) still said they would not allow the donation of organs of a relative declared brain dead, even if they were not sure whether their family member would have a problem with becoming an organ donor. Even when families have favorable attitudes toward organ donation, discrepancies between the willingness to consent to donate and the refusal at the bedside can be attributed to an unresolved dilemma: aiding people or protecting the body of the deceased[13]. Generally, those who have an unfavorable attitude toward donation are more afraid of the manipulation and disfiguration of the body, and they have a preference for a whole or intact body after death. The importance of the integrity of the body has been shown to be an important barrier to organ donation. It has been reported that in Denmark, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Romania, and other countries some people will reject organ donation in an effort to preserve the integrity of the body because of religious reasons[13,20-22]. In reality, there are differences between religion and the perception or understanding of religion in society regarding human life.

In Islam as an example, there is the belief that believers will resurrect with all their organs after life and that their organs will testify for their life on the earth. This common belief that organ donation is not approved by Islamic religion is a major obstacle for organ donation in countries with Muslim majorities like Turkey[23]. In fact, organ transplantation and donation are permissible in Islam. Islamic teachings and scriptures encourage saving lives, treating disease, relieving suffering, and eliminating harm. A patient has the option to receive organs from a deceased donor in order to replace his/her damaged organs. In this context, preventing harm takes priority over preserving the body of the deceased. In addition to Islam, studies have shown that faith leaders are united in their support for organ donation and in general, faith or belief groups are not against organ donation in principle[24,25]. In China, traditional cultural practices also exert a negative influence on people’s willingness to donate their organs. Traditional Chinese culture holds that people should keep the body intact up to their burial or cremation, which is treated as an expression of respect for the dead, ancestors, and for nature[26]. In another study, the decision-making process was described by the relatives of a potentially brain-dead donor, as complex, mainly because relatives had to make a decision on behalf of the deceased. Three conditions contributing to this complexity were mentioned: The time limit to make the decision created a sense of urgency, the request for consent for the donation was made immediately after the relatives had heard that their beloved one had suffered a brain death, making it difficult to focus on the request while they were grieving. Most relatives who refused consent for donation said that they were not competent to decide in such a crisis[13].

Other barriers to organ donation and registration in the donor registry were reported by a national study from Denmark, and are based on people's doubts about their own ability to perform the registration and to cope with the consequences, knowledge, outcome expectations, and concerns about what others will think of them for agreeing to the donation[27]. According to the international registry of organ donation, cadaveric organ donation in Turkey was 0.7 per million population in 2000, and increased to around 7.5 in 2018. This organ donation rate, despite increasing, is still significantly lower than Western countries such as Spain (48 per million population). The reason for Turkey’s increase in organ donation rate corresponds with an increase in the number of transplant centers, popularization on social media platforms, fewer contradicting/false media reports regarding organ donation, and increased exposure to trends in Western countries. In our opinion, any effort to increase the organ donation rate should be focused on children of school-going age and young individuals.

Public education programs are needed to increase awareness among the general population about the legislation related to organ donation[28]. There is a clear need that every individual in a society should be well informed about organ donation and transplantation issues in order to contribute to efforts to increase low donation rates. Young people form a section of the population in whom early awareness is important to encourage favorable attitudes toward donation, as they can influence their families in all aspects of organ donation and transplantation. In Turkey, 21.9% of the population are students. School-based health education was also identified as a promising approach to improve organ donation rates among ethnically diverse youth. The impact of a classroom intervention was examined in a multicultural high school population. After an educational session, students in the intervention group demonstrated a significant increase in knowledge scores, as well as a positive movement in opinion regarding a willingness to donate. The positive changes in opinion occurred independent of ethnicity and gender, in spite of both being negative predictors of opinion at baseline[29]. These results demonstrate that even a single instance of classroom exposure can impact knowledge levels, correct misinformation, and affect attitude change on organ donation among an ethnically diverse adolescent population. Moreover, there is a trend of recruiting faith leaders to overcome religious barriers to organ donation, and to increase donor registration among different faith groups[30,31].

This study showed that the general population in Turkey has inadequate knowledge on organ donation and consequently a less positive attitude. In order to create greater awareness of organ donor scarcity and ultimately recruit more potential organ donors, public policymakers have taken up a wide range of actions, including the development of extensive media campaigns. Educational campaigns are seen as an important tool in all countries and in medical communities to promote a positive perception of organ donation.

Organ transplant waiting lists continue to increase yearly, and the unavailability of adequate organs for transplantation to meet the existing demand has resulted in a major shortage. Public awareness of organ donation and knowledge about organ procurement fundamentally affects the organ transplantation programs and is positively correlated with signing an organ donor card. To improve the supply of donor organs, continued efforts and strategic planning are required; however, little is known about the attitudes and knowledge of the Turkish general population. As a consequence, there is insufficient knowledge of what characterizes and distinguishes people’s viewpoints, and how this could inform the development of adequate and effective policies to promote organ donation.

A large number of patients with organ failure die while on the waiting list because of the lack of available organs; many also become too sick for transplant while waiting and get dropped from the list. We aimed to evaluate the attitudes, awareness, and knowledge levels of the Turkish adult population toward organ donation to determine strategies and to highlight issues important for policies-makers to change attitudes and behaviors, and to promote organ donation and reduce the organ shortage in the country.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate attitudes, awareness, and knowledge levels of the Turkish adult population. Data from this study could help analyze people’s viewpoints and to uncover possible barriers to organ donation, which might exist in the community.

We surveyed 3000 adult individuals in Turkey. To ensure a representative sample, we used Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics. Adult individuals were distributed equally between city centers and towns based on relative population densities. Data were collected by PRP Research and Consultancy Company using computer-assisted personal interviewing.

This study showed that only 33.9% of the respondents thought that they had enough information regarding organ donation, with 36.7% indicating that they had no information at all about organ donation. The three main sources of information were found to be television programs, internet platforms, and healthcare professionals. The majority of participants (88.3%) said that they would not consider donating an organ in the future. Reasons not to donate included: It was too soon to decide on organ donation, concerns about body deterioration, religious beliefs, and concerns about procedure errors like removing organs before brain death. While the majority would not consider donating an organ, most (87.9%) said they would accept an organ donation if they suffered from organ failure, and the majority (67%) said they would donate an organ to a close relative.

In conclusion, our results showed that the general population in Turkey has inadequate information on organ donation, and must be better informed before an adequate increase in organ donation rate can be expected. Many barriers to organ donation were identified, including misperceptions and misinformation related to donation procedures and religious views with regard to organ donation and body integrity. This further stresses the importance of education to clarify information and overcome the existing barriers to organ donation.

The general populations in Turkey have inadequate information and have many misperceptions and misinformation on organ donation. Further studies are needed to test the effectiveness of education in changing attitude and improving donation rate in the country.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Saner F S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Arshad A, Anderson B, Sharif A. Comparison of organ donation and transplantation rates between opt-out and opt-in systems. Kidney Int. 2019;95:1453-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tokalak I, Kut A, Moray G, Emiroglu R, Erdal R, Karakayali H, Haberal M. Knowledge and attitudes of high school students related to organ donation and transplantation: a cross-sectional survey in Turkey. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2006;17:491-496. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Wakefield CE, Watts KJ, Homewood J, Meiser B, Siminoff LA. Attitudes toward organ donation and donor behavior: a review of the international literature. Prog Transplant. 2010;20:380-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Uskun E, Ozturk M. Attitudes of Islamic religious officials toward organ transplant and donation. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:E37-E41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ozer A, Ekerbicer HC, Celik M, Nacar M. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of officials of religion about organ donation in Kahramanmaras, an eastern Mediterranean city of Turkey. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3363-3367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Adam R, Karam V, Cailliez V, O Grady JG, Mirza D, Cherqui D, Klempnauer J, Salizzoni M, Pratschke J, Jamieson N, Hidalgo E, Paul A, Andujar RL, Lerut J, Fisher L, Boudjema K, Fondevila C, Soubrane O, Bachellier P, Pinna AD, Berlakovich G, Bennet W, Pinzani M, Schemmer P, Zieniewicz K, Romero CJ, De Simone P, Ericzon BG, Schneeberger S, Wigmore SJ, Prous JF, Colledan M, Porte RJ, Yilmaz S, Azoulay D, Pirenne J, Line PD, Trunecka P, Navarro F, Lopez AV, De Carlis L, Pena SR, Kochs E, Duvoux C; all the other 126 contributing centers (www. eltr.org) and the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). 2018 Annual Report of the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR) - 50-year evolution of liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2018;31:1293-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sayahi N, Ates K, Suleymanlar G. Current Status of Renal Replacement Therapies in Turkey: Turkish Society of Nephrology Registry 2015 Summary Report. Turkish J Nephrol. 2017;26:154-60. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Keten HS, Keten D, Ucer H, Cerit M, Isik O, Miniksar OH, Ersoy O. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of mosque imams regarding organ donation. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:598-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shaheen FA, Souqiyyeh MZ. Current obstacles to organ transplant in Middle Eastern countries. Exp Clin Transplant. 2015;13 Suppl 1:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Emek E, Yesim Kara Z, Demircan FH, Serin A, Yazici P, Sahin T, Tokat Y, Bozkurt B. Analysis of the Liver Transplant Waiting List in Our Center. Transplant Proc. 2019;51:2413-2415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abukhaizaran N, Hashem M, Hroub O, Belkebir S, Demyati K. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Palestinian people relating to organ donation in 2016: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2018;391 Suppl 2:S45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ríos A, López-Navas AI, Navalón JC, Martínez-Alarcón L, Ayala-García MA, Sebastián-Ruiz MJ, Moya-Faz F, Garrido G, Ramirez P, Parrilla P. The Latin American population in Spain and organ donation. Attitude toward deceased organ donation and organ donation rates. Transpl Int. 2015;28:437-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | de Groot J, van Hoek M, Hoedemaekers C, Hoitsma A, Smeets W, Vernooij-Dassen M, van Leeuwen E. Decision making on organ donation: the dilemmas of relatives of potential brain dead donors. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Delgado J, Molina-Pérez A, Shaw D, Rodríguez-Arias D. The Role of the Family in Deceased Organ Procurement: A Guide for Clinicians and Policymakers. Transplantation. 2019;103:e112-e118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lei L, Deng J, Zhang H, Dong H, Luo Y, Luo Y. Level of Organ Donation-Related Knowledge and Attitude and Willingness Toward Organ Donation Among a Group of University Students in Western China. Transplant Proc. 2018;50:2924-2931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kose OO, Onsuz MF, Topuzoglu A. Knowledge levels of and attitudes to organ donation and transplantation among university students. North Clin Istanb. 2015;2:19-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mikla M, Rios A, Lopez-Navas A, Klimaszewska K, Krajewska-Kulak E, Martinez-Alarcón L, Ramis G, Ramirez P, Lopez Montesinos MJ. Organ Donation: What Are the Opinions of Nursing Students at the University of Bialystok in Poland? Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2482-2484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Conesa C, Ríos A, Ramírez P, Canteras M, Rodríguez MM, Parrilla P. [Multivariate study of psychosocial factors that influence the population's attitude towards organ donation]. Nefrología. 2005;25:684. |

| 19. | Ríos A, Cascales P, Martínez L, Sánchez J, Jarvis N, Parrilla P, Ramírez P. Emigration from the British Isles to southeastern Spain: a study of attitudes toward organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2020-2030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nordfalk F, Olejaz M, Jensen AM, Skovgaard LL, Hoeyer K. From motivation to acceptability: a survey of public attitudes towards organ donation in Denmark. Transplant Res. 2016;5:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Agrawal S, Binsaleem S, Al-Homrani M, Al-Juhayim A, Al-Harbi A. Knowledge and attitude towards organ donation among adult population in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2017;28:81-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | El Hangouche AJ, Alaika O, Rkain H, Najdi A, Errguig L, Doghmi N, Aboudrar S, Cherti M, Dakka T. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of organ donation in Morocco: A cross-sectional survey. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29:1358-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Tarhan M, Dalar L, Yildirimoglu H, Sayar A, Altin S. The View of Religious Officials on Organ Donation and Transplantation in the Zeytinburnu District of Istanbul. J Relig Health. 2015;54:1975-1985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Randhawa G, Brocklehurst A, Pateman R, Kinsella S, Parry V. Faith leaders united in their support for organ donation: findings from the UK Organ Donation Taskforce study. Transpl Int. 2010;23:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bruzzone P. Religious aspects of organ transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1064-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wu Y, Elliott R, Li L, Yang T, Bai Y, Ma W. Cadaveric organ donation in China: A crossroads for ethics and sociocultural factors. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e9951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vorstius Kruijff PE, Witjes M, Jansen NE, Slappendel R. Barriers to Registration in the National Donor Registry in Nations Using the Opt-In System: A Review of the Literature. Transplant Proc. 2018;50:2997-3009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Scheuher C. What Is Being Done to Increase Organ Donation? Crit Care Nurs Q. 2016;39:304-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cárdenas V, Thornton JD, Wong KA, Spigner C, Allen MD. Effects of classroom education on knowledge and attitudes regarding organ donation in ethnically diverse urban high schools. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:784-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rady MY, Verheijde JL. Campaigning for Organ Donation at Mosques. HEC Forum. 2016;28:193-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Randhawa G, Neuberger J. Role of Religion in Organ Donation-Development of the United Kingdom Faith and Organ Donation Action Plan. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:689-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |