Published online Jun 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2181

Peer-review started: March 14, 2020

First decision: April 14, 2020

Revised: April 19, 2020

Accepted: May 13, 2020

Article in press: May 13, 2020

Published online: June 6, 2020

Processing time: 86 Days and 1.2 Hours

Bone transport and distraction osteogenesis has been widely used to treat bone defects after traumatic surgery, but, skin and soft tissue incarceration can be as high as 27.6%.

To investigate the efficacy of inserting a tissue expander to prevent soft tissue incarceration.

Between January 2016 and December 2018, 12 patients underwent implantation of a tissue expander in the subcutaneous layer in the vicinity of a tibial defect to maintain the soft tissue in position. A certain amount of normal saline was injected into the tissue expander during surgery and was then gradually extracted to shrink the expander during the course of transport distraction osteogenesis. The tissue expander was removed when the two ends of the tibial defect were close enough.

In all 12 patients, the expanders remained intact in the subcutaneous layer of the bone defect area during the course of transport distraction osteogenesis. When bone transport was adequate, the expander was removed and the bone transport process was completed. During the whole process, there was no incarceration of skin and soft tissue in the bone defect area. Complications occurred in one patient, who experienced poor wound healing.

The pre-filled expander technique can effectively avoid soft tissue incarceration. The authors’ primary success with this method indicates that it may be a valuable tool in the management of incarcerated soft tissue.

Core tip: Bone transport and distraction osteogenesis has been widely used to treat bone defects after traumatic surgery, but skin and soft tissue incarceration can be as high as 27.6%. Skin and soft tissue incarceration often occurs in the late stage of bone transport. Considering that there is currently no ideal solution, the authors devised a new method to prevent the possible formation of skin and soft tissue incarceration using a tissue expander.

- Citation: Chen H, Teng X, Hu XH, Cheng L, Du WL, Shen YM. Application of a pre-filled tissue expander for preventing soft tissue incarceration during tibial distraction osteogenesis. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(11): 2181-2189

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i11/2181.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2181

The orthofix external fixator or the ring fixator to repair a long bone defect, also known as the bone transport technique, is a very effective reconstruction method, and presently, this method is widely used in clinical practice[1]. During the process of bone transport, soft tissue incarceration between the two tibial ends is not rare. Tissue expansion is a technique in which a tissue expander is inserted in a certain tissue layer during the primary stage of surgery (also known as the pre-filling stage), and subsequently, a certain amount of normal saline is regularly injected through the valves to gradually expand the overlying tissue and the skin layer until its surface area increases due to the tension and amplification effect. When the expander reaches a certain capacity and the surface area of the skin is adequate, the expander is removed and the excess skin is used to reconstruct a skin and soft tissue defect. In the present study, a tissue expander was inserted in the defect area between the tibial ends to prevent possible skin and soft tissue incarceration during bone transport and distraction osteogenesis. The effects of this method are discussed.

From January 2016 to December 2018, 10 male patients and 2 female patients, aged 26 to 68 years (average age 40.6 years), were admitted to our burns unit. All patients had a tibial defect. Seven cases had experienced a traffic injury, 1 case had experienced a drifting-down injury, 2 cases had experienced a bruise injury caused by a heavy object, and 2 cases had experienced a machine injury. The interval between injury and admission to our unit ranged from 5 h to 1 year. All 12 cases presented with a unilateral tibiofibular fracture, and one of these 12 cases had accompanying multiple fractures and traumatic shock. All 12 cases displayed a pretibial skin defect and bone exposure, and they were reconstructed by the use of flaps and/or skin grafting in the early stage after trauma, including free flap transplantation in 6 cases, myocutaneous flap transfer in 3 cases, island flap transfer in 2 cases, and skin grafting in one case. During the process of wound repair, 9 patients developed an infectious sinus tract in the bone defect area, and the infection was finally controlled by debridement and sequestrum removal. The defect in the tibia was 7-15 cm in size; and the defect was located in the upper segment of the tibia in 7 cases, in the middle segment of the tibia in 3 cases, and the lower segment of the tibia in 2 cases.

X-ray images were obtained to measure the patient's limb length and to determine the location and length of the tibial defect. The appropriate volume and shape of the expander were then selected. Surgery was a two-stage operation, in which the first stage involved implantation of a tissue expander, injection of a certain amount of normal saline, and handling of the two fracture ends; and the second stage consisted of removal of the expander. During the interval between the two stages, distraction was performed as routine practice and normal saline in the expander was gradually extracted. Osteotomy was performed before or after expander insertion or simultaneously with expander insertion. Of the 12 cases included in this study, osteotomy in 6 cases was performed simultaneously with expander insertion, osteotomy in 4 cases was carried out before expander insertion and osteotomy in 2 cases was performed after expander insertion.

Tissue expander implantation: Before insertion into the tibial ends, it was ensured that the expander was in a good condition without any infiltration or distortion problems. The expander was placed on the surface of the skin over the tibial defect area, the coverage of the expander was marked, and the position of the valve was designed.

An incision, long enough to accommodate the expander and to handle the distal and proximal ends of the bone, was made at the appropriate location at the marked edge. The two bone ends were exposed through the incision. In patients who had undergone antibiotic-polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) bead implantation previously, the bead was removed and the lacuna accommodated the expander easily. In patients who had not undergone antibiotic-PMMA bead implantation, the subcutaneous tissue occupied the bone ends and the lacuna was additionally dissected. Simultaneously, the bone ends were smoothed with a rongeur or osteotribe. If the bone ends were covered with a callus without sharp protrusion, the callus was preserved. A subcutaneous tunnel was created near the incision to accommodate the valve and the catheter of the expander. The tissue expander was implanted, a drainage tube was placed beneath the expander, and the incision was sutured. After suturing was completed, an appropriate amount of normal saline was injected into the expander to lift the skin in the bone defect area to ensure that the surface of the defect area was at the same horizontal level as the adjacent skin.

Distraction osteogenesis was initiated on day 10 after osteotomy at the rate of 0.5 to 1.00 mm per day. Distraction was stopped or slowed down for some days in the case of severe pain. Transport was directed towards an ischemic regenerate to produce its compaction until its bony parts contacted each other. As the two ends of the bone defect were close to each other, the skin overlying the expander area swelled and protruded from the normal skin surface. A certain amount of the liquid in the expander was extracted from the valve every two weeks, and the skin surface in this area was lowered back to the same horizon as the surrounding normal skin or slightly below the horizon. Regular follow-up was of great significance during this period. First, the overlying skin surface of the bone defect area was neither protruding nor hollow to the adjacent skin; if this was not the case, a certain amount of normal saline in the expander was extracted. Second, the rate and frequency of distraction were altered to observe whether the trend of bone end to end and the formation of a bone callus at the osteotomy end was normal; an X-ray was obtained, if necessary (Table 1).

| Expander related check-list | Fixator related check-list |

| Skin surface should be horizontal to the surrounding skin | Distance moved on threaded rods compared to the previous visit |

| Skin tension should not be very high | The range of motion of adjacent joints and physiotherapy |

| Signs of expander leakage | Neurological examination |

| Valve stability | Pin sites for signs of inflammation |

| Signs of inflammation | Stability of the frame and components |

| Ambulation | |

| Assessment of complications such as muscle contracture and joint subluxation |

Tissue expander removal: When the two ends of the bone defect were close enough or they had met the requirements of orthopedic treatment, the expander was removed. The operation was performed when it was possible to handle the bone ends synchronously with expander removal. In this study, the distance between the two bone ends was less than 1 cm in 11 cases and 5 cm in 1 case when the expander was removed. A skin incision was made along the original surgical approach to expose the expander. The cystic cavity inner wall of the subcutaneous expander was relatively smooth and well-preserved. We dealt with the interposed soft tissue, smoothed the broken ends, removed the sequestrum to ensure that the marrow cavity was not obstructed, and shortened the fibula. Bone grafting was performed when necessary.

Results were based on the following five criteria: (1) Absence of interposed skin and soft tissue incarceration; (2) Absence of skin piercing due to the broken bone ends; (3) Good wound healing after expander insertion; (4) Absence of valve-related problems, such as valve twist, valve translocation, or puncture failure; and (5) Absence of expander leakage or exposure.

The average length of the tibial defect was 9.6 cm (range, 7-15 cm), and the capacity of the tissue expander was 50 mL in 11 cases and 500 mL in one case. The average expansion time was 162 d (range, 109-236 d), and the distraction osteogenesis process was completed with the distance between bone ends being less than 1 cm in 11 cases and 5 cm in one case (this patient underwent acute tibial shortening and the expander was removed in advance). Skin collapse, skin incarceration, skin piercing, expander leakage, and valve-related problems were absent in all 12 cases. Complications occurred in one case who experienced poor wound healing due to skin tension caused by a scar.

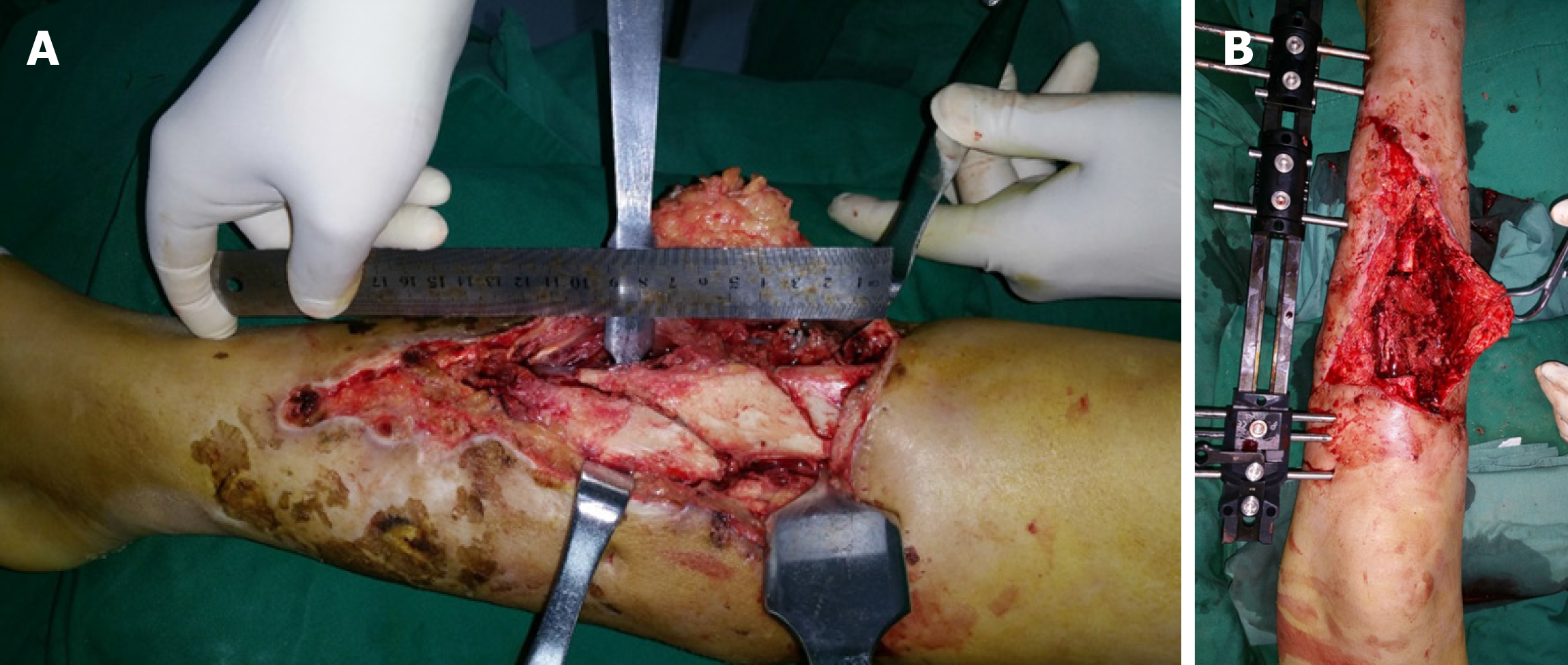

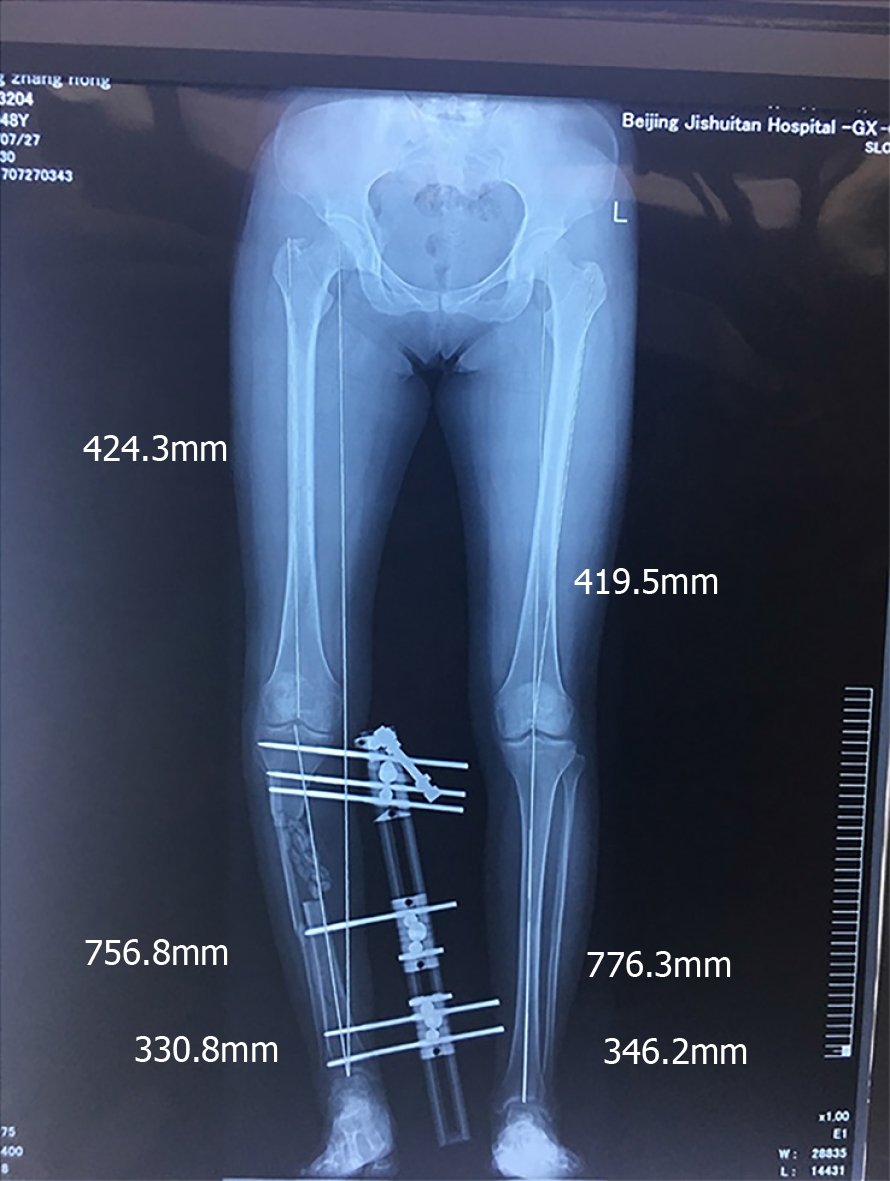

A typical case who experienced an open fracture of the right tibia and fibula underwent tissue expander surgery to prevent soft tissue incarceration during tibial distraction osteogenesis after a traffic accident. The length of the necrotic tibia was approximately 9 cm and the necrotic tissue was completely removed by debridement (Figure 1A and B) and antibiotic-PMMA beads were implanted intraoperatively (Figure 2). Three months later, antibiotic-PMMA beads were removed from the lacuna (Figure 3A), the expander was inserted and filled (Figure 3B and C), the external fixator was adjusted, and fibular osteotomy and distal tibial osteotomy were performed.

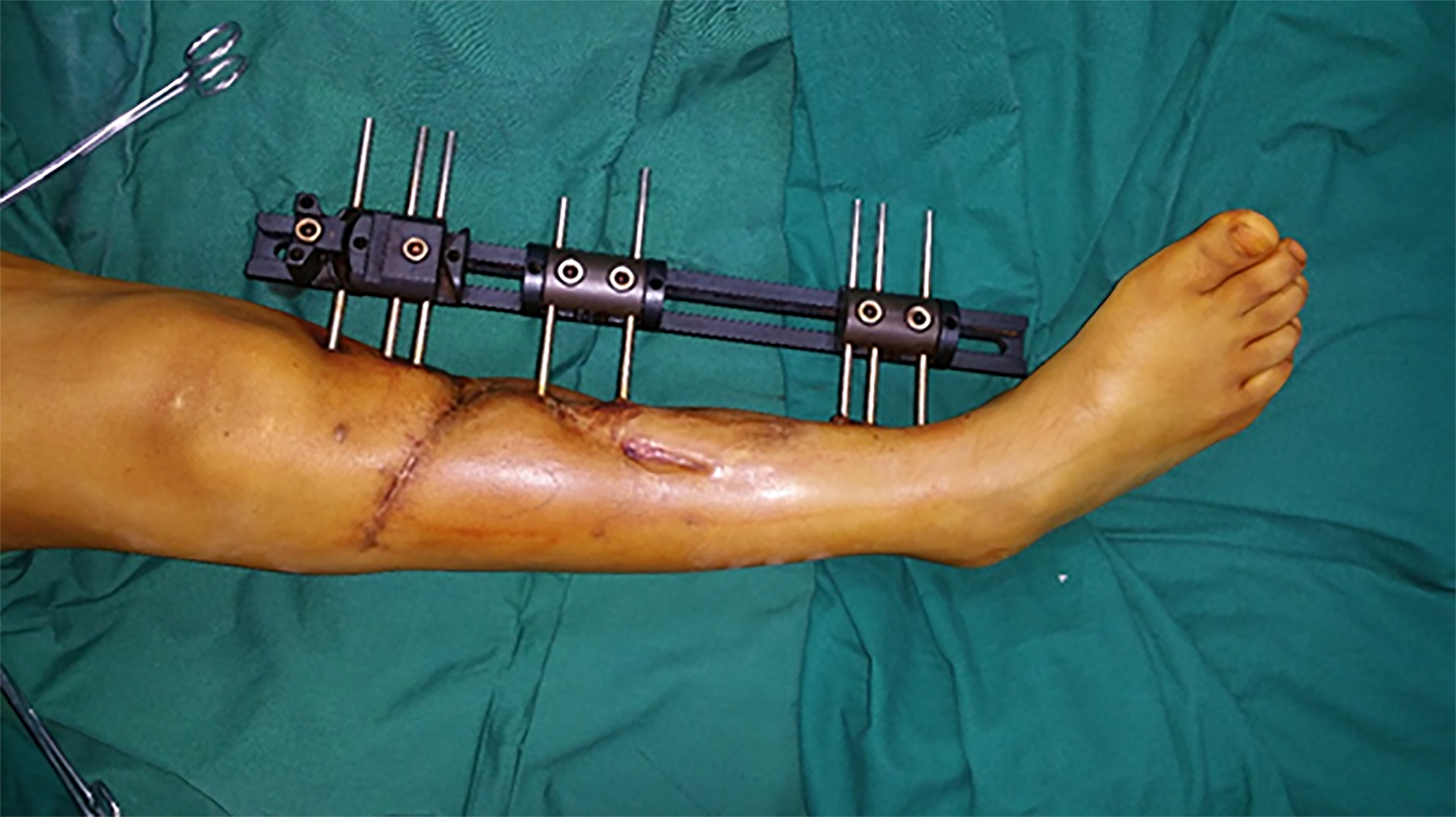

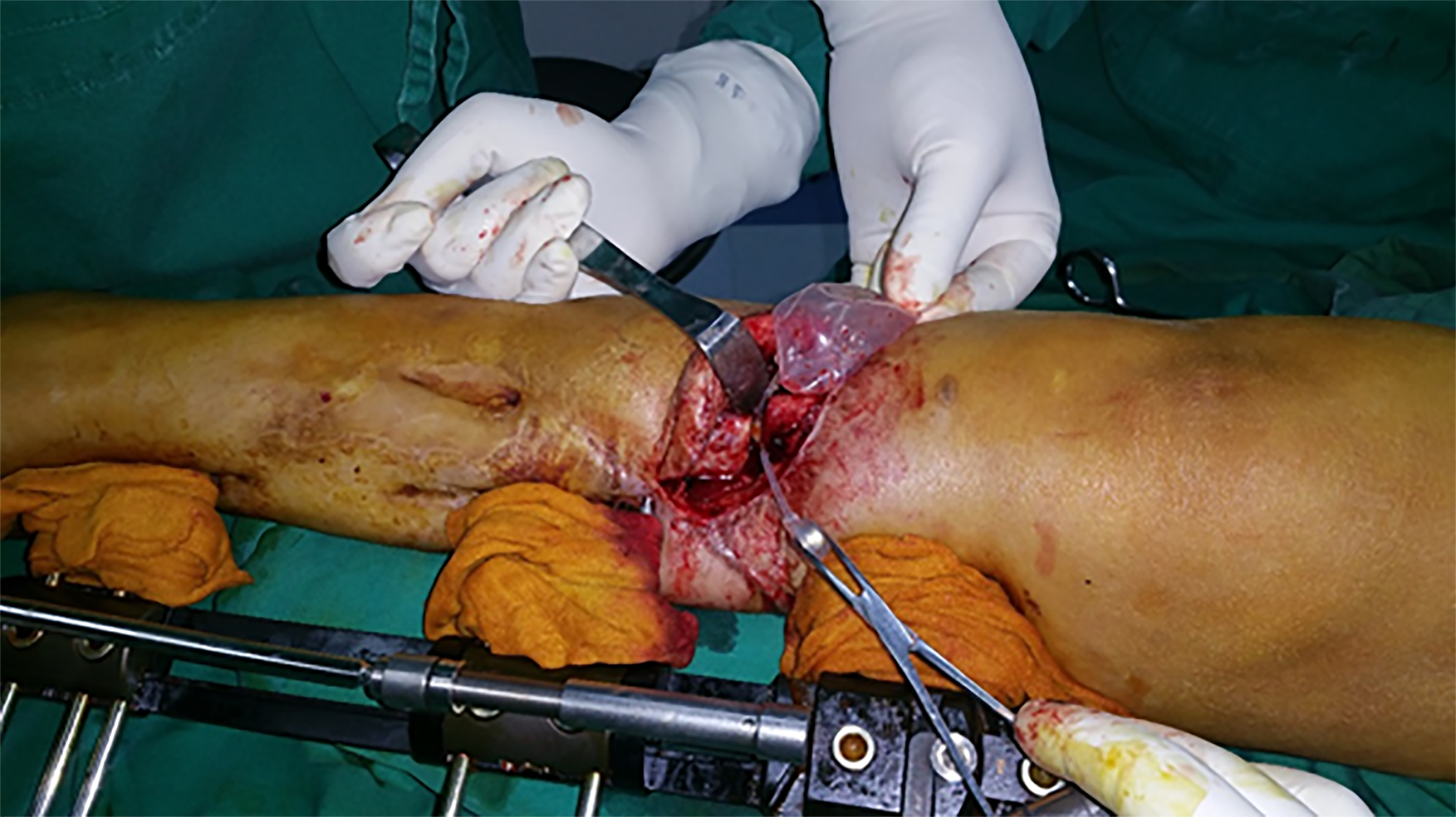

Distraction in order to produce bone transport was started 10 d after surgery at a rate of 1 mm/d (4 times per day, 1/4 mm each time), and an appropriate amount of liquid was extracted from the valve every two weeks to maintain the skin and skin surface of the bone defect area basically at the same horizontal level as the normal skin surface. The procedure was stopped for one week because the patient complained of pain or discomfort. At 126 d after surgery, the distance between the two bone ends was less than 1 cm (Figure 4). During this entire period, tissue incarceration did not occur (Figure 5). Expander removal and fibular osteotomy were then performed (Figure 6). During surgery, we dealt with interposed soft tissue, rounded off sharp bone prominences, removed the sequestrum to ensure that the marrow cavity was not obstructed, and shortened the fibula. Good incision healing was achieved postoperatively (Figure 7).

Bone transport and distraction osteogenesis has been widely used to treat bone defects after traumatic surgery, and the procedure has stood the test of time and has consistently provided good results[2,3]. For tibial reconstruction, the indication is a bone gap larger than 3 cm[4]. Compared with bone transport at other sites, skin and soft tissue incarceration is more likely to occur during the tibial transport procedure. According to the literature, its incidence is as high as 27.6% (8/29) and it is more common in the proximal transport type than the distal transport type, irrespective of the type of external fixator and soft tissue condition.

Skin and soft tissue incarceration often occurs during the late stage of bone transport. The vast majority of patients who require an operation are those with tibial bone defects. The possible reasons for this occurrence may be subcutaneous structural abnormalities or off-vertical pins. In order to prevent skin collapse, it has been reported that the interposed skin should overhang the fixator using stitches, but the effect is not reliable. Also, there were cases in which a wire was used instead of stitches to protect the skin from collapse according to a report in the literature, in which a satisfactory result was obtained, but trauma to the body was worse, and caused great inconvenience during dressing change and wound nursing. However, in patients with poor skin conditions in collapsed or even incarcerated areas, the bone end is likely to puncture the skin to form ulceration and bone exposure[5]. In summary, currently there is no optimal method to prevent the possible formation of skin and soft tissue incarceration during tibial bone transport.

Mechanical manipulation of the skin, first introduced in the 1950s, has been a valuable tool in reconstructive surgeries due to excellent cosmetic results, ease of use, and lack of rejection[6]. A tissue expander is widely used in plastic surgery[7,8]. It is being increasingly used in traumatic surgery[9,10], especially in two aspects, one aspect is insertion into the surrounding normal skin of the scar or another type of damage to increase the skin area to cover the defect; the other aspect is insertion into the subcutaneous tissue to improve the appearance of defects caused by lesions such as breast augmentation after breast carcinoma surgery. In these two aspects, the expanders are inflated and are then gradually deflated. Adversely, the area between the bone ends becomes smaller as distraction osteogenesis advances; therefore, we developed a new use of the expanders in which the expander can be inflated or deflated according to the need to increase or decrease its capacity. To the authors’ knowledge, reverse application of continuous external expansion has never been reported in bone transport. As a result, the expander can prevent the disposed skin from bulging; on the other hand, it can also avoid excessive inflation to prevent hampering the two bone ends approaching each other. In addition, the capsule cavity formed by the expander makes it convenient to process the two bone ends in the later stage. In our study, all 12 patients achieved a satisfactory result.

In practice, attention should be paid to the following details: (1) Indications: According to the literature, patients with tibial transport osteogenesis have a higher incidence of skin and soft tissue incarceration, which is more often seen in the proximal-distal type. Furthermore, we conclude that the larger the defects in bone, the longer the change in subsurface structures. As a result, the possibility of skin and soft tissue incarceration is likely to increase. Therefore, we suggest that for a tibial defect of more than 5 cm, implantation of a pre-filled tissue expander can be routinely considered, especially for a tibial defect in the lower segment. The presence of an obvious local infection is an absolute contraindication for the procedure; (2) Expander capacity considerations: We prefer to choose expanders with a relatively smaller capacity for two reasons. First, the expander is prone to developing folds and can pierce the skin as the fluid is extracted and the expanders shrink. Second, the expander itself can be excessively expanded up to 3 times its original capacity. We suggest that when a bone defect is less than 10 cm, a cylindrical expander of 30-50 mL is adequate; when a bone defect is larger than 10 cm, a cylindrical expander of 50-100 mL is preferred; (3) Treatment of bone defects and broken ends: the expander is easily damaged by sharp instruments and most of the expander will directly contact the bone end or can even be affected by the pressure of the bone end; therefore, the bone ends need to be rounded off using an osteotribe or abrasive drilling; and (4) Prophylactic use of antibiotics: To prevent possible infection by Staphylococcus aureus, first generation cephalosporin or penicillin should be administered 0.5-2 h before surgery. Almost all patients have developed wound infection previously and have obtained bacterial culture results. When necessary, prophylactic antibiotics could be used according to the preoperative bacterial culture results.

Initially, the role of the expander was that of a spacer, which was used to avoid collapse of the soft tissue into the bone defect area during the process of transport distraction osteogenesis, and the reason why the authors preferred not to remove the membrane of the cyst wall was to prevent excessive bleeding. After performing a literature review, the authors realized that the main role of the expander is biological by inducing a foreign body in the surrounding membrane, which was first described by Masquelet et al[11] in 1986. Experimental studies have shown that the membrane is richly vascularized and is composed of fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and collagen. In addition, the membrane secretes vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor and bone morphogenetic protein-2 and these growth factors play important roles in accelerating bone healing and augmenting new bone development especially in the first 4 wk[12-15]. In our study, besides functioning as a spacer to prevent soft tissue incarceration, the expander plays the role of a foreign body and biologically active membrane is induced to promote healing of the broken ends. After the second stage of surgery, the membrane is kept intact. Research has demonstrated that the expander capsule contains myofibroblasts, which are involved in elastic contraction of the expanded flap, and the expander capsule played a role in facilitating restoration of the expanded flap to its the normal position in our study.

Based on our experience of the 12 cases included in our study, it was proved that a pre-filled expander can effectively prevent the collapse and incarceration of skin and soft tissue that may occur during tibial transport and can reduce adverse complications after transport osteogenesis. However, the limitation of this study lies in its small sample size; it is necessary to include more cases in future studies. After referring to domestic and foreign literature, the method reported in this study is actually the first treatment method of this type that offers advantages such as simple operation procedure and strong practicability, and it is worth performing this method in clinical practice.

Bone transport and distraction osteogenesis has been widely used to treat bone defects after traumatic surgery; however, skin and soft tissue incarceration is high.

The authors inserted a tissue expander in the defect area between the tibial ends to prevent possible skin and soft tissue incarceration during bone transport and distraction osteogenesis.

In this study, the authors aimed to investigate the efficacy of inserting a tissue expander to prevent soft tissue incarceration.

Twelve patients underwent implantation of a tissue expander in the subcutaneous layer in the vicinity of a tibial defect to maintain the soft tissue in position.

The expanders remained intact in the subcutaneous layer of the bone defect area during the course of transport distraction osteogenesis in all 12 patients. During the whole process, there was no incarceration of skin and soft tissue in the bone defect area. Complications occurred in one patient, who experienced poor wound healing.

The authors’ primary success with this method indicates that it may be a valuable tool in the management of incarcerated soft tissue. The pre-filled expander technique can effectively avoid incarceration.

After referring to domestic and foreign literature, the method reported in this study is actually the first treatment method of this type that offers advantages such as simple operation procedure and strong practicability, and it is worth performing this method in clinical practice in the future.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Imai K, Shimizu Y S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Singh AK, Parihar M, Bokhari S. The Evaluation of the Radiological and Functional Outcome of Distraction Osteogenesis in Patients with Infected Gap Nonunions of Tibia Treated by Bone Transport. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:559-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ilizarov GA. Transosseous osteosynthesis. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer, 1992. |

| 3. | De Bastiani G, Aldegheri R, Renzi-Brivio L, Trivella G. Limb lengthening by callus distraction (callotasis). J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rigal S, Merloz P, Le Nen D, Mathevon H, Masquelet AC; French Society of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology (SoFCOT). Bone transport techniques in posttraumatic bone defects. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:103-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hu XH, Huang L, Chen Z, DU WL, Wang C, Shen YM. Effect of a combination of local flap and sequential compression-distraction osteogenesis in the reconstruction of post-traumatic tibial bone and soft tissue defects. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:2846-2851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Neumann CG. The expansion of an area of skin by progressive distention of a subcutaneous balloon; use of the method for securing skin for subtotal reconstruction of the ear. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946). 1957;19:124-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rohrich RJ. The "Advances in Breast Reconstruction" Supplement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:1S-2S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zöllner AM, Buganza Tepole A, Kuhl E. On the biomechanics and mechanobiology of growing skin. J Theor Biol. 2012;297:166-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Formby P, Flint J, Gordon WT, Fleming M, Andersen RC. Use of a continuous external tissue expander in the conversion of a type IIIB fracture to a type IIIA fracture. Orthopedics. 2013;36:e249-e251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arain AR, Cole K, Sullivan C, Banerjee S, Kazley J, Uhl RL. Tissue expanders with a focus on extremity reconstruction. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018;15:145-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Masquelet AC, Begue T. The concept of induced membrane for reconstruction of long bone defects. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41:27-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Christou C, Oliver RA, Yu Y, Walsh WR. The Masquelet technique for membrane induction and the healing of ovine critical sized segmental defects. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Aho OM, Lehenkari P, Ristiniemi J, Lehtonen S, Risteli J, Leskelä HV. The mechanism of action of induced membranes in bone repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:597-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gouron R, Petit L, Boudot C, Six I, Brazier M, Kamel S, Mentaverri R. Osteoclasts and their precursors are present in the induced-membrane during bone reconstruction using the Masquelet technique. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;11:382-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pelissier P, Masquelet AC, Bareille R, Pelissier SM, Amedee J. Induced membranes secrete growth factors including vascular and osteoinductive factors and could stimulate bone regeneration. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:73-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |