Published online May 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i9.1073

Peer-review started: December 27, 2018

First decision: January 19, 2019

Revised: February 23, 2019

Accepted: March 16, 2019

Article in press: March 16, 2019

Published online: May 6, 2019

Processing time: 101 Days and 17.5 Hours

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is an uncommon congenital anomaly of the pancreatic and biliary ductal system, defined as a union of the pancreatic and biliary ducts located outside the duodenal wall. According to the Komi classification of PBM, the common bile duct (CBD) directly fuses with the ventral pancreatic duct in all types. Pancreas divisum (PD) occurs when the ventral and dorsal ducts of the embryonic pancreas fail to fuse during the second month of fetal development. The coexistence of PBM and PD is an infrequent condition. Here, we report an unusual variant of PBM associated with PD in a pediatric patient, in whom an anomalous communication existed between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct.

A boy aged 4 years and 2 mo was hospitalized for abdominal pain with nausea and jaundice for 5 d. Abdominal ultrasound showed cholecystitis with cholestasis in the gallbladder, dilated middle-upper CBD, and a strong echo in the lower CBD, indicating biliary stones. The diagnosis was extrahepatic biliary obstruction caused by biliary stones, which is an indication for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). ERCP was performed to remove biliary stones. During the ERCP, we found a rare communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct. After clearing the CBD with a balloon, an 8.5 Fr 4-cm pigtail plastic pancreatic stent was placed in the biliary duct through the major papilla. Six months later, his biliary stent was removed after he had no symptoms and normal laboratory tests. In the following 4-year period, the child grew up normally with no more attacks of abdominal pain.

We consider that ERCP is effective and safe in pediatric patients with PBM combined with PD, and can be the initial therapy to manage such cases, especially when it is combined with aberrant communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct.

Core tip: The coexistence of pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) and pancreas divisum is an infrequent condition. According to the Komi classification of PBM, the common bile duct (CBD) directly fuses with the ventral pancreatic duct in all types. However, we present a case who had an anomalous communication existing between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct. There is lack of therapeutic experience for such a case. We successfully diagnosed and treated the little child by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The child remained asymptomatic during 4 yr of follow-up.

- Citation: Cui GX, Huang HT, Yang JF, Zhang XF. Rare variant of pancreaticobiliary maljunction associated with pancreas divisum in a child diagnosed and treated by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(9): 1073-1079

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i9/1073.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i9.1073

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is an uncommon congenital anomaly of the pancreatic and biliary ductal system, defined as a union of the pancreatic and biliary ducts located outside the duodenal wall[1]. Because of this anatomical anomaly, PBM has been frequently associated with cholelithiasis, cholangitis, pancreatitis[2], and increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma[3]. PBM has been classified into three types by Komi et al[4], according to the angle of the junction of the common bile duct (CBD) and pancreatic duct, dilatation of the common channel, and the running of the dorsal pancreatic duct. Types I and II have no pancreas divisum (PD). In type III, PD exists in all PBM patients with complete PD in types IIIa and b and incomplete PD in types IIIc1–3. According to the Komi classification of PBM, the CBD directly fuses with the ventral pancreatic duct in all types. PD occurs when the ventral and dorsal ducts of the embryonic pancreas fail to fuse during the second month of fetal development. It is the most common anatomical variant of the pancreas, in which ventral duct drains the minor part of the pancreas through the major papilla, whereas the dorsal duct drains the major part of the pancreatic juice through the minor papilla[5]. The coexistence of PBM and PD is an infrequent condition.

Here, we report an unusual variant of PBM associated with PD in a pediatric patient, in whom an anomalous communication existed between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct. Our case was hardly classified into Komi classification of PBM with the special anatomical variant. The patient was successfully diagnosed and managed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Written informed consent was obtained from his parents prior to the endoscopic therapy.

A boy aged 4 years and 2 mo was hospitalized for abdominal pain with nausea and jaundice for 5 d.

He had colic pain located in the right upper abdomen, without radiating to the back or paroxysmal attacks and with no confirmed exacerbating or relieving factors. He was sent to a local hospital after the first attack. Abdominal ultrasound indicated gallbladder muddy stones and CBD stones. After symptomatic treatment, he was referred to our institution for further diagnosis and therapy.

Neither he nor his family had any past history of biliaro-pancreatic diseases or other abnormalities.

Physical examination revealed mild tenderness in the middle upper abdomen without rebound tenderness. Slight jaundice was observed in his sclera.

Routine blood tests showed an inflammatory result: white blood cell count, 11.4 × 109/L; neutrophils, 78.9%; and hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), 20 mg/L. Liver biochemical function tests indicated extrahepatic biliary obstruction: alanine aminotransferase, 78 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 55 U/L; γ-glutamyl tran-speptidase, 210 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 441 U/L; total bilirubin, 40.5 μmol/L; and direct bilirubin, 33.1 μmol/L. The level of serum amylase was elevated (135 U/L). The serum autoimmune antibody tests including IgG 4 were negative.

Abdominal ultrasound showed cholecystitis with cholestasis in the gallbladder, dilated middle-upper CBD with a diameter of 1.1 cm, and a strong echo in the lower CBD, indicating biliary stones. Computed tomography was not performed because of the radiation risk.

These findings above supported a diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary obstruction caused by biliary stones, which is an indication for ERCP.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

PBM associated with PD with a communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct; CBD stones with acute cholangitis

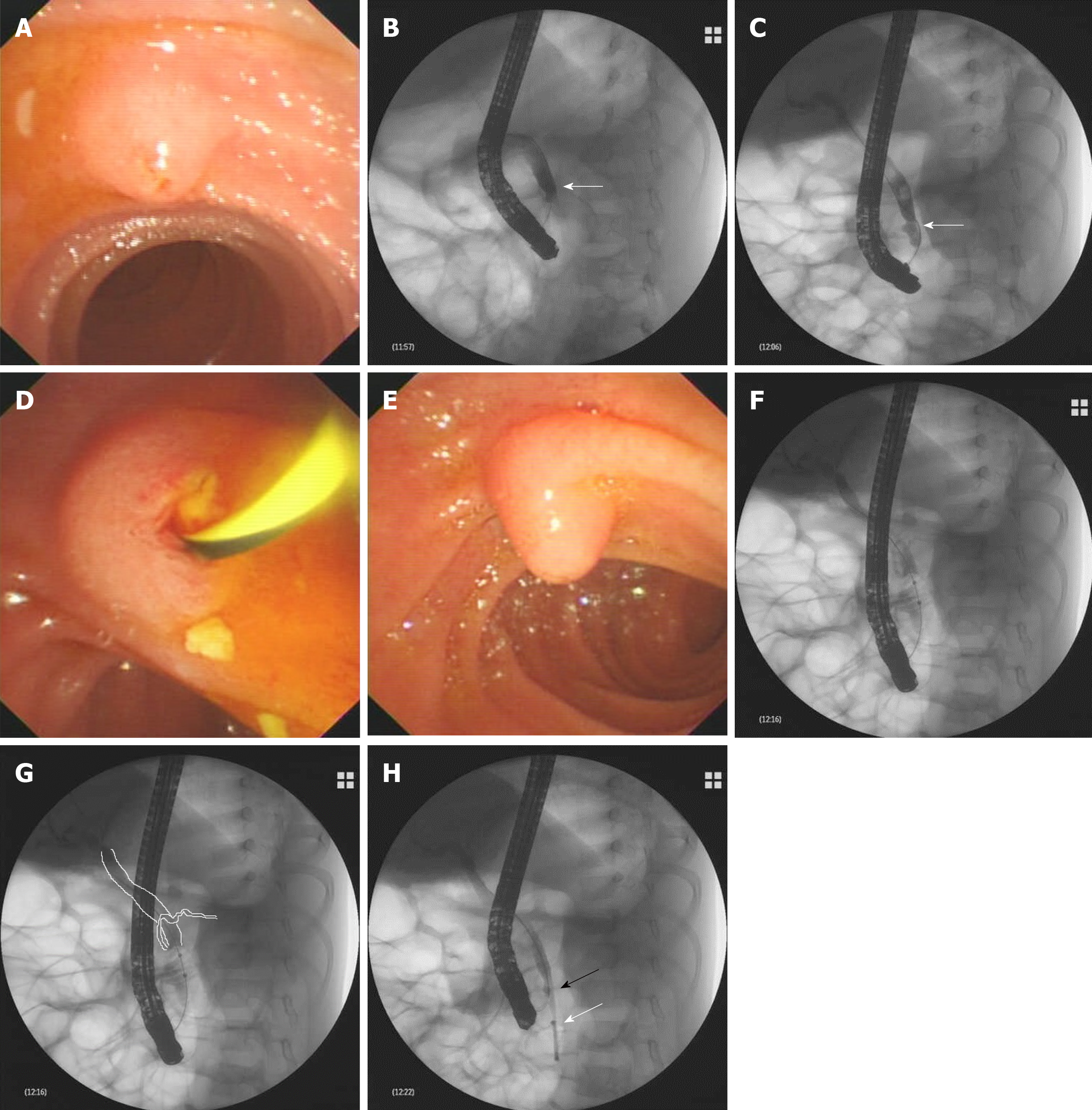

ERCP was performed to remove biliary stones. When the duodenoscope was advanced to the descending part of the duodenum, a hemispheric papilla with a villus-like opening was seen, which resembled the major papilla in both size and morphology (Figure 1A). This was wrongly considered to be the major papilla and cannulation was successfully carried out. X-ray examination after injecting a contrast agent into the papilla revealed a dilated CBD with a diameter of 0.9 cm, which was indicative of biliary stones (Figure 1B). However, the main pancreatic duct was not revealed. A minor endoscopic sphincterotomy was then performed, after which multiple small biliary stones were discharged from the papilla (Figure 1D). However, in a short distance beneath the papilla, another bigger papilla was detected, which was in fact the real major papilla (Figure 1E). The prior one was the minor papilla. After successful cannulation of the major papilla, the CBD was dilated with multiple filling defects, indicating biliary stones. However, the Wirsung duct was not observed. The middle–lower CBD was narrowed (Figure 1C). An endoscopic balloon was used to remove the biliary stones. During the process of pulling the balloon combined with injecting a contrast agent into the biliary tract, the dorsal pancreatic duct was unexpectedly revealed at the level of the middle–lower part CBD, which is rarely seen under normal conditions (Figure 1F and G). After clearing the CBD with the balloon, an 8.5 Fr 4-cm pigtail plastic pancreatic stent was placed in the biliary duct through the major papilla. Finally, the minor papilla was cannulated again and the guidewire was advanced into the CBD accompanying the biliary stent (Figure 1H), from which a communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct was created.

After the procedure, the child recovered uneventfully. Six months later, his biliary stent was removed after he had no symptoms and normal laboratory tests. In the following 4-year period with periodic telephone call and outpatient visits, the child grew up normally with no more attacks of abdominal pain.

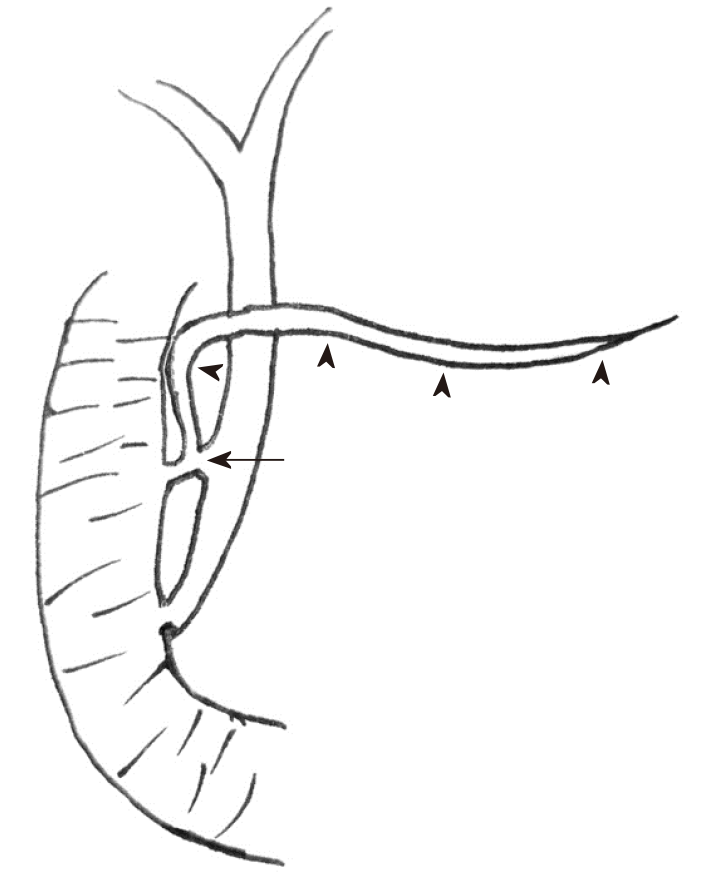

PBM is a congenital anomaly that occurs when the pancreatic and bile ducts are united outside the duodenal wall. In patients with PBM, the sphincter of Oddi functionally loses its effect on the union of the two ducts. Therefore, continuous reciprocal reflux between pancreatic juice and bile occurs, which can result in various pathological conditions in the biliary tract and pancreas[2]. Under normal circumstances, the hydrostatic pressure in the pancreatic duct is usually higher than that in the bile duct, which means that the pancreatic juice more frequently refluxes into the biliary duct than the pancreatic duct in PBM[6]. This might be an etiological factor in choledocholithiasis, inflammatory ductal epithelial changes, distal common bile duct strictures, and recurrent attacks of acute cholangitis. Additionally, PBM resulting in chronic inflammation of the bile duct is considered to be frequently related to biliary tract malignancy. PD occurs when the ventral and dorsal ducts of the embryonic pancreas fail to fuse during the second month of fetal development[5]. It is the most frequent congenital anomaly of the pancreas in which the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts drain separately into the duodenum. The dominant pancreatic juice is drained by the dorsal pancreatic duct through the minor papilla. Whether PD causes pancreatitis or other complications remains controversial. The co-occurrence of PBM and PD is an uncommon condition. Terui et al[7] found that PD was detected in one of 71 cases of PBM, with an incidence rate of 1.4%. In the current study, as shown in the schematic illustration (Figure 2), our case had three pancreaticobiliary abnormalities: PBM, PD, and abnormal communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct.

Currently, the Komi classification for PBM has been widely accepted and utilized, which influences the selection of type of surgical procedure and prognosis after surgery, especially in patients with complicating cases like type IIIc3[4]. In the Komi classification, all terminal CBDs join the ventral pancreatic duct. Matsumoto et al[8] retrospectively analyzed 202 patients with PBM to develop a new concept of the embryonic etiology of PBM. They found no patients in whom the terminal bile duct was joined with the dorsal pancreatic duct, nor was there a communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct. However, not all PBM cases can be classified according to the Komi classification. A few complicated PBM cases with rare anatomical variants have been reported by a small number of researchers[9-11]. Parlak et al[9] reported a 42-year-old woman who underwent ERCP for recurrent biliary pain attacks. During ERCP, the dilated CBD was found to fuse to the dorsal pancreatic duct directly without common channel dilation. Therefore, they thought that it represented a new type of PBM that could not be included in the Komi classification. Zhang et al[10] reported four complicated PBM cases, in which the CBD also joined the dorsal pancreatic duct in a direct way. All four cases were female with the youngest aged 11 years. They were successfully treated with intraductal drainage by ERCP. McMahon et al[11] reported an anomalous communication between the dorsal pancreatic duct and CBD via a small ventral pancreatic duct branch. This patient was a 30-year-old woman who suffered from chronic debilitating pain for several years. The patient’s anomaly was indicated by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with intravenous secretin administration. She received a Whipple pancreatico-duodenectomy combined with cholecystectomy. The aberrant ductal communication was confirmed by the resected specimen.

In our case, we found a communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct, which was similar to that reported by McMahon et al[11]. The little difference is that the communication in our case was located closer to the minor papilla. Although no definite communication was delineated by ERCP, the CBD was clearly observed by cannulation of both papillae. Moreover, the dorsal pancreatic duct was developed when removing the biliary stones with the balloon at the middle-lower level of the CBD via the major papilla. This may have been caused by high-pressure injection of contrast agent into the dorsal pancreatic duct via the communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct when the balloon was pulled down. We speculated that the communicating pancreatic duct was located at the middle-lower level of the CBD. As indicated earlier, all previously reported cases with this rare anomaly were female, with the youngest being aged 11 years[9-11]. However, in the present case, the child was male and aged 4 years.

To date, MRCP as a noninvasive approach is the first choice for diagnosis of pancreaticobiliary disorders. However, MRCP is limited in diagnosing the common biliopancreatic duct and biliopancreatic junction, compared with ERCP[12-14], even when secretin is used[15]. Diagnostic accuracy may be increased using 3D or dynamic MRCP with secretin stimulation[16]. For diagnosing patients with anatomical maljunction, ERCP remains the gold standard. In the current case, the patient was successfully diagnosed by ERCP.

PBM is generally recognized to be a risk factor for biliary tract malignancy[3]. Here, surgery is considered as radical treatment for patients with PBM. Timely surgical division of the biliary and pancreatic ducts is essential for patients with PBM to prevent free reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary tract, regardless of the presence or absence of choledochal cyst[17-20]. ERCP is also a useful therapeutic option for patients with PBM, and it can be used to relieve acute biliary obstruction by removing biliary stones, implanting a biliary stent, or sphincterotomy[12-14]. It is helpful to plan the timing and choice of the appropriate surgical procedure. Samavedy et al[21] studied the potential benefit of ERCP in patients with PBM and found that 13 of 15 cases presenting with relapsing pancreatitis benefiting from endoscopic therapy. They assumed that ERCP was the logical first step to manage most symptomatic patients with PBM. Until now, only one similar patient with rare variant communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct has been reported, who underwent surgical treatment at age 30 years[11]. There is lack of therapeutic experience for such cases. In our case, given the factors of age, growth, and surgical trauma to the body, ERCP was chosen as initial therapy. During ERCP, an endoscopic balloon was used to remove the biliary stones and place a biliary stent through the major papilla. The child remains asymptomatic during 4 yr of follow-up. Furthermore, close long-term follow-up is needed to supervise the development of biliary malignancy.

In summary, timely diagnosis and treatment of PBM associated with PD are important, especially when it is combined with aberrant communication between the CBD and dorsal pancreatic duct. We consider that ERCP is effective and safe in pediatric patients with PBM combined with PD, and can be the initial therapy to manage such cases. Considering the potential of PBM to develop into biliary malignancy, close follow-up is needed for small children after endoscopic therapy. Once the evidence of neoplastic degeneration is detected during follow-up, timely surgical therapy should be adopted.

This case had been presented as a clinical case presentation at UEGW 2018, Vienna, Austria.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Isik A, Mariani A, Kin T S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Kamisawa T, Ando H, Hamada Y, Fujii H, Koshinaga T, Urushihara N, Itoi T, Shimada H; Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction. Diagnostic criteria for pancreaticobiliary maljunction 2013. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Babbitt DP, Starshak RJ, Clemett AR. Choledochal cyst: a concept of etiology. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;119:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Funabiki T, Matsubara T, Miyakawa S, Ishihara S. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:159-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Komi N, Takehara H, Kunitomo K, Miyoshi Y, Yagi T. Does the type of anomalous arrangement of pancreaticobiliary ducts influence the surgery and prognosis of choledochal cyst? J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:728-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Klein SD, Affronti JP. Pancreas divisum, an evidence-based review: part I, pathophysiology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:419-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Csendes A, Kruse A, Funch-Jensen P, Oster MJ, Ornsholt J, Amdrup E. Pressure measurements in the biliary and pancreatic duct systems in controls and in patients with gallstones, previous cholecystectomy, or common bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:1203-1210. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Terui K, Hishiki T, Saito T, Sato Y, Takenouchi A, Saito E, Ono S, Kamata T, Yoshida H. Pancreas divisum in pancreaticobiliary maljunction in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:419-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Matsumoto Y, Fujii H, Itakura J, Mogaki M, Matsuda M, Morozumi A, Fujino MA, Suda K. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction: etiologic concepts based on radiologic aspects. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:614-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Parlak E, Köksal AŞ, Eminler AI. New type of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction in a patient wıth choledochal cyst. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang Y, Sun W, Zhang F, Huang J, Fan Z. Pancreaticobiliary maljuction combining with pancreas divisum: Report of four cases. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:8-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McMahon CJ, Vollmer CM, Goldsmith J, Brown A, Pleskow D, Pedrosa I. An unusual variant of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction in a patient with pancreas divisum diagnosed with secretin-magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Pancreas. 2010;39:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | De Angelis P, Foschia F, Romeo E, Caldaro T, Rea F, di Abriola GF, Caccamo R, Santi MR, Torroni F, Monti L, Dall'Oglio L. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in diagnosis and management of congenital choledochal cysts: 28 pediatric cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:885-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Saito T, Terui K, Mitsunaga T, Nakata M, Kuriyama Y, Higashimoto Y, Kouchi K, Onuma N, Takahashi H, Yoshida H. Role of pediatric endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in an era stressing less-invasive imaging modalities. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:204-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hiramatsu T, Itoh A, Kawashima H, Ohno E, Itoh Y, Sugimoto H, Sumi H, Funasaka K, Nakamura M, Miyahara R, Katano Y, Ishigami M, Ohmiya N, Kaneko K, Ando H, Goto H, Hirooka Y. Usefulness and safety of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in children with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Carnes ML, Romagnuolo J, Cotton PB. Miss rate of pancreas divisum by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in clinical practice. Pancreas. 2008;37:151-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Kamata N. MRCP of congenital pancreaticobiliary malformation. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Iwai N, Fumino S, Tsuda T, Ono S, Kimura O, Deguchi E. Surgical treatment for anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary duct with nondilatation of the common bile duct. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1794-1796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ono S, Tokiwa K, Iwai N. Cellular activity in the gallbladder of children with anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary duct. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:962-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Işık A, Grassi A, Soran A. Positive Axilla in Breast Cancer; Clinical Practice in 2018. Eur J Breast Health. 2018;14:134-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Isik A, Firat D, Yilmaz I, Peker K, Idiz O, Yilmaz B, Demiryilmaz I, Celebi F. A survey of current approaches to thyroid nodules and thyroid operations. Int J Surg. 2018;54:100-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Samavedy R, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic therapy in anomalous pancreatobiliary duct junction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:623-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |