Published online May 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i9.1021

Peer-review started: February 26, 2019

First decision: March 10, 2019

Revised: March 20, 2019

Accepted: April 9, 2019

Article in press: April 9, 2019

Published online: May 6, 2019

Processing time: 72 Days and 19.8 Hours

In paediatric patients with complicated nephrotic syndrome (NS), rituximab (RTX) administration can induce persistent IgG hypogammaglobulinemia among subjects showing low basal immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels.

To evaluate the effect of RTX on IgG levels and infections in patients with complicated NS and normal basal IgG levels.

We consecutively enrolled all patients with complicated NS and normal basal IgG levels undergoing the first RTX infusion from January 2008 to January 2016. Basal IgG levels were dosed after 6 wk of absent proteinuria and with a maximal interval of 3 mo before RTX infusion. The primary outcome was the onset of IgG hypogammaglobulinemia during the follow-up according to the IgG normal values for age [mean ± standard deviation (SD)].

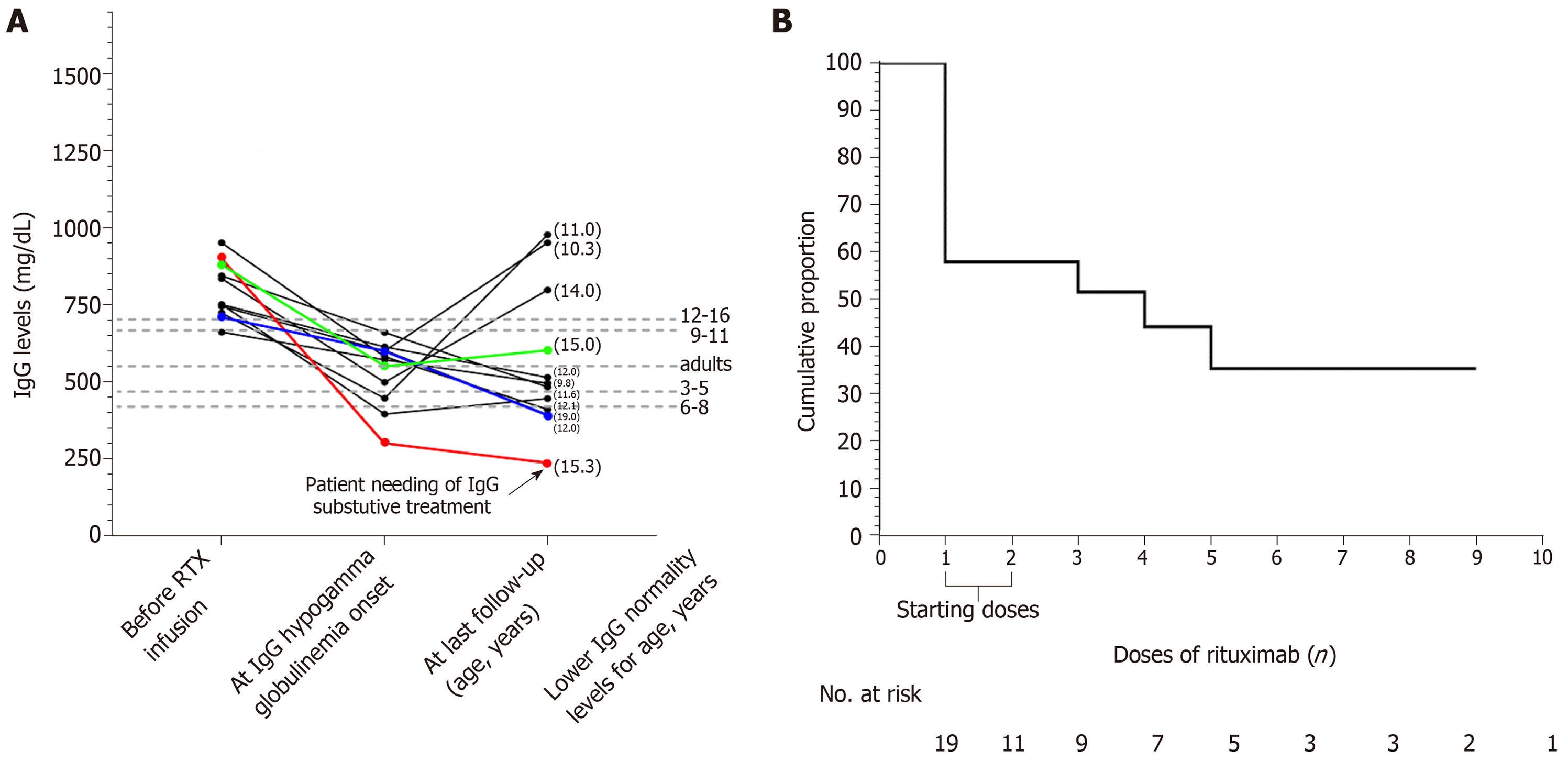

We enrolled 20 patients with mean age at NS diagnosis of 4.2 ± 3.3 years. The mean age at the first RTX infusion was 10.9 ± 3.5 years. Eleven out of twenty patients (55%) developed IgG hypogammaglobulinemia. None of these patients showed severe or recurrent infections. Only one patient suffered from recurrent acute otitis media and underwent substitutive IgG infusion. Three patients undergoing only the two “starting doses” experienced normalization of IgG levels. Using Kaplan-Meier analysis, the cumulative proportion of patients free of IgG hypogammaglobulinemia was 57.8% after the first RTX dose, 51.5% after the third dose, 44.1% after the fourth dose, and 35.5% after the fifth dose.

RTX can induce IgG hypogammaglobulinemia in patients with pre-RTX IgG normal values. None of the treated patients showed severe infections.

Core tip: In paediatric patients with complicated nephrotic syndrome (NS), rituximab (RTX) administration can induce persistent immunoglobulin G (IgG) hypogammaglobulinemia among subjects showing low basal IgG levels. Our case series shows that RTX can induce IgG hypogammaglobulinemia also in patients with pre-RTX IgG normal values and that persisting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia could be dose-dependent. When evaluating a patient with complicated NS and post-RTX IgG hypogammaglobulinemia, IgG supplementation may not be needed because, to date, no severe infections have been detected and the possibility of adverse events related to IgG supplementation exists.

- Citation: Marzuillo P, Guarino S, Esposito T, Di Sessa A, Orsini SI, Capalbo D, Miraglia del Giudice E, La Manna A. Rituximab-induced IgG hypogammaglobulinemia in children with nephrotic syndrome and normal pre-treatment IgG values. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(9): 1021-1027

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i9/1021.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i9.1021

Rituximab (RTX) is an effective and safe treatment for childhood-onset, complicated, frequently relapsing, and steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome (NS)[1]. Data about long-term safety are limited. Recent reports have highlighted the impact of RTX treatment on immunoglobulin (Ig) levels. In studies involving adults with multisystem autoimmune diseases, it had been found that following RTX treatment 34%-56% of patients showed reduced IgG levels, with 13%-26% of them presenting already IgG level reduction before RTX initiation[2-4]. On the other hand, it has been shown in paediatric patients with NS that RTX administration can induce persistent IgG hypogammaglobulinemia among subjects showing low basal IgG levels and in a few cases with normal baseline IgG levels[5-7]. The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of RTX on IgG levels and infections in patients with complicated, frequently relapsing, and steroid- and cyclosporine-dependent NS who have normal baseline IgG levels.

We consecutively enrolled patients with complicated NS and normal basal IgG levels undergoing the first RTX infusion from January 2008 to January 2016. The study was approved by our Research Ethical Committee. Informed consent was obtained before any procedure.

Basal IgG levels were dosed after 6 wk of absent proteinuria and with a maximal interval of 3 mo before RTX infusion. Patients with IgG levels under the range of normality for age before the first RTX infusion [mean ± standard deviation (SD)] and with missing data were excluded[8].

Initial RTX course was performed as two infusions of 375 mg/m2 with an interval of 7-14 d between the two infusions (“starting doses”). Additional RTX injections were made after every NS relapse just after obtaining remission independently from the levels of CD19-positive cells. IgG levels, white cell blood count, and CD19-positive cells were evaluated at 3 mo and 6 mo after the first RTX infusion and then every 6 mo. After RTX initiation, we slowly tapered cyclosporine dose before stopping completely and then slowly tapered corticosteroid doses stopping their ad-ministration.

The primary outcome was the onset of IgG hypogammaglobulinemia during the follow-up according to normal IgG values for age (mean ± SD) (Figure 1A)[8]. We also documented possible recovery from IgG hypogammaglobulinemia and recorded infections and neutropenia.

P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Differences for continuous variables were analysed with the independent-sample t test for normally distributed variables and with the Mann-Whitney test in case of non-normality. Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-squared test. The development of primary outcome was determined by survival analysis according to the Kaplan-Meier method. The day of first RTX infusion was considered the starting point, while the end point was the date of the primary outcome onset. Patients arriving at their last available follow-up without showing primary outcome were right censored. The Stat-Graph XVII software for Windows was used for all statistical analyses with the exception of Kaplan-Meir analysis, which was done using Graphpad Prims 7 software for Windows (La Jolla, CA, United States).

A total of 20 patients were enrolled. The mean age of the study population at the time of NS diagnosis was 4.2 ± 3.3 years (range 1.6-11.5 years). All patients developed complicated, frequently relapsing, and steroid- and cyclosporine-dependent NS and were treated with the “starting doses” of RTX at mean age of 10.9 ± 3.5 years. RTX doses were repeated in 11 patients because of NS relapses. Therefore, a total of 79 doses of RTX were administered in the study period: Only the two “starting doses” in eight patients, three doses in 2 patients, four doses in five patients, five doses in 1 patient, seven doses in 1 patient, eight doses in 2 patients, nine doses in 1 patient. The mean follow-up available after the last RTX infusion was 29.8 ± 17.5 mo.

IgG hypogammaglobulinemia after RTX therapy was recorded in 11/20 (55%) patients. In 8 out of 11 patients, IgG hypogammaglobulinemia occurred after the RTX “starting doses” and in the remaining three patients after the subsequent doses (Figure 1A). Only 3 out of the 11 patients experienced subsequent normalization of IgG levels. These 3 patients underwent only the two “starting doses” of RTX and did not receive further RTX infusions. None of the patients who developed IgG hypogammaglobulinemia showed severe infections. Only one patient (Figure 1A) suffered from recurrent acute otitis media and underwent substitutive IgG infusion after immunological consultation. The first episode of NS in this patient was at the age of 1.6 years. Before the RTX infusion, he showed 16 NS relapses despite cor-ticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate treatments. This patient underwent his first RTX doses at 6.8 years of age and showed persisting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia after the fifth dose of RTX. After the eighth RTX dose, he had six episodes of acute otitis media in 8 mo. Therefore, substitutive IgG infusion was started. He has undergone substitutive IgG infusions for 18 mo, and he has not shown other acute otitis media episodes.

CD19-positive cell depletion was found in all the patients with a mean recovery time of 6.3 ± 17.5 mo from every RTX infusion. None of the patients showed neutropenia. When comparing patients showing and not showing IgG hypogam-maglobulinemia, no differences were found in the utilization of corticosteroids, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, other immunosuppressive agents, and more than one immunosuppressive agent (Table 1). The months of follow-up after the last RTX infusion, the number of RTX infusions, and the months of CD-19 cells depletion were similar between patients showing and not showing IgG hypogammaglobulinemia. Moreover, a non-significant trend showing a lower number of relapses after RTX infusion and younger age at first RTX infusion for the patients presenting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia compared with the patients not presenting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia was present (Table 1).

| Presenting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia, n = 11 | Not presenting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia, n = 9 | P-value | |

| Age at NS onset, yr | 2.8 (1.1) | 5.2 (4.7) | 0.07 |

| Female sex n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (33.3) | 0.1 |

| Corticosteroids n (%) | 11 (100) | 9 (100) | > 0.99 |

| Corticosteroids (mean ± SD, mo) | 76.5 ± 54.2 | 73.2 ± 30.9 | 0.87 |

| Cyclosporine n (%) | 11 (100) | 9 (100) | > 0.99 |

| Cyclosporine (mean ± SD, mo) | 56.1 ± 23.1 | 66.4 ± 40.0 | 0.48 |

| Cyclophosphamide n (%) | 8 (72.3) | 6 (66.7) | 0.9 |

| Cyclophosphamide (mean ± SD, mo) | 3 ± 0.27 | 3 ± 0.33 | 0.9 |

| Other immunosuppressive agents n (%) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.33) | 0.43 |

| > 1 immunosuppressive agents n (%) | 8 (72.3) | 7 (77.8) | 0.43 |

| Relapses (mean ± SD) | 11.5 ± 4.6 | 16.5 ± 9.7 | 0.15 |

| Relapses after first RTX infusion (mean ± SD) | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 3.9 ± 4.6 | 0.15 |

| RTX infusions (mean ± SD) | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 2.7 | 0.11 |

| Age at first RTX infusion, (mean ± SD, yr) | 9.2 ± 1.8 | 11.8 ± 4.5 | 0.09 |

| Months of CD19-positive cells depletion (mean ± SD) | 6.4 ± 3 | 6.2 ± 2.6 | 0.9 |

| Months of follow-up after the last RTX infusion (mean ± SD) | 31.1 ± 14.9 | 27.4 ± 20.7 | 0.59 |

Using Kaplan-Meier analysis, the cumulative proportion of patients free of IgG hypogammaglobulinemia was 57.8% after the first dose of RTX, 51.5% after the third dose, 44.1% after the fourth dose, and 35.5% after the fifth dose (Figure 1B).

Evidence on the impact of RTX treatment on IgG levels in children with complicated NS having normal baseline IgG levels are limited to few cases for each available study[5-7]. Delbe-Bertin et al[5] reported that persisting post-RTX IgG hypo-gammaglobulinemia was observed in 7 patients with IgG hypogammaglobulinemia before RTX infusion, while none of the 4 patients with normal pre-RTX IgG levels presented IgG hypogammaglobulinemia after RTX initiation. In addition, Fujinaga et al[6] found that nine out of 60 patients with complicated steroid-dependent NS showed hypogammaglobulinemia (defined as IgG levels < 500 mg/dL) after RTX infusion. Among these 9 patients, only 3 patients had normal IgG levels before the RTX infusion. In another multi-centre case series, Guigonis et al[7] found that 4 out of 22 patients with severe steroid- and cyclosporine-dependent NS developed RTX-related hypogammaglobulinemia. In that case series, no further follow-up of IgG levels was reported.

The present single-centre study was specifically designed to enrol only patients with complicated, frequently relapsing, and steroid- and cyclosporine-dependent NS with normal basal IgG levels. We found that 11 out of 20 patients (55%) developed IgG hypogammaglobulinemia after RTX therapy, with eight of them having developed IgG hypogammaglobulinemia after the “starting doses” and three after the following RTX doses. Noteworthy, we found recovery from IgG hypo-gammaglobulinemia only in the 3 who underwent “starting doses” of RTX without receiving further RTX infusions. None of the patients who developed IgG hypogammaglobulinemia showed severe infections. Only one patient (Figure 1A) suffered from recurrent acute otitis media, and he underwent substitutive IgG infusion

We failed to demonstrate potential risk factors of developing IgG hypo-gammaglobulinemia after RTX treatment in patients with NS probably because of the limited population number. However, we did identify a trend showing that the patients developing IgG hypogammaglobulinemia were younger both at NS onset and first RTX infusion than patients who did not develop IgG hypogam-maglobulinemia. In the literature, data about risk factors of developing post-RTX hypogammaglobulinemia in children with NS are not yet available. However, more than one course of RTX, previous exposure to purine analogues, more than eight doses of RTX, RTX maintenance regimens, age at the administration of RTX, and post-RTX mycophenolate administration have been identified as risk factors in adults undergoing RTX administration because of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic Lupus Erythematous[9].

Regarding the risk of severe infections following RTX infusion in paediatric patients affected by NS, among the 27 patients showing post-RTX IgG hypogammaglobulinemia (including our patients and other in the literature with available follow-up)[5,6], no life-threatening infections were detected. Among non-life-threatening infections, one patient presented bronchitis[6], one enteritis[6], and one recurrent episodes of acute otitis media. Moreover, evaluating the need of substitutive IgG infusion, 4 out of the 27 patients underwent IgG supplementation. Among these 4 patients, 3 received IgG supplementation only for low IgG levels[5,6], and one for recurrent acute otitis media. It is important to emphasize that one of these patients in IgG supplementation presented aseptic meningitis as an adverse effect of IgG supplementation[5].

Finally, evaluating the percentage of recovery of serum levels of IgG in patients developing IgG hypogammaglobulinemia, Fujinaga et al[6] showed IgG levels recovery in 6 out of 9 patients, Delbe-Bertin et al[5] showed IgG recovery in 1 out of 8 patients, and in the present case series we found IgG recovery in 3 out of 11 patients.

In conclusion, our case series shows that RTX can induce IgG hypogam-maglobulinemia in patients with pre-RTX IgG normal values and that persisting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia could be dose-dependent.

When evaluating a patient with complicated NS and post-RTX IgG hypo-gammaglobulinemia, IgG supplementation may not be needed because, to date, no severe infections have been detected and the possibility of adverse events related to IgG supplementation exists.

It has been shown in paediatric patients with complicated nephrotic syndrome (NS) that rituximab (RTX) administration can induce persistent IgG hypogammaglobulinemia among subjects showing low basal IgG levels.

RTX is an effective and safe treatment for childhood-onset, complicated, frequently relapsing, and steroid-dependent NS. Data about long-term safety are limited. Evidence on the impact of RTX treatment on IgG levels in children with complicated NS having normal baseline IgG levels are limited to a few cases for each available study. Here, we aimed to provide further evidence about RTX safety in childhood and provide a way for possible future perspective multi-centre studies about this topic.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of RTX on IgG levels and infections in patients with complicated, frequently relapsing, and steroid- and cyclosporine-dependent NS with normal baseline IgG levels.

We consecutively enrolled all patients with complicated NS and normal basal IgG levels undergoing the first RTX infusion from January 2008 to January 2016. Basal IgG levels were dosed after 6 wk of absent proteinuria and with a maximal interval of 3 mo before RTX infusion. The primary outcome was the onset of IgG hypogammaglobulinemia during the follow-up according to IgG normal values for age (mean ± SD).

We enrolled 20 patients with a mean age at NS diagnosis of 4.2 ± 3.3 years. The mean age at the first RTX infusion was 10.9 ± 3.5 years. Eleven out of twenty patients (55%) developed IgG hypogammaglobulinemia. None of these patients showed severe or recurrent infections. Only one patient suffered from recurrent acute otitis media and underwent substitutive IgG infusion. Three patients undergoing only the two “starting doses” experienced normalization of IgG levels. When comparing patients showing and not showing IgG hypogammaglobulinemia, no differences were found in the utilization of corticosteroids, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, other immunosuppressive agents, and more than one immunosuppressive agent. A non-significant trend showing a lower number of relapses after RTX infusion and younger age at first RTX infusion for the patients presenting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia compared with the patients not presenting IgG hypogammaglobulinemia was present. Using Kaplan-Meier analysis, the cumulative proportion of patients free of IgG hypogammaglobulinemia was 57.8% after the first RTX dose, 51.5% after the third, 44.1% after the fourth, and 35.5% after the fifth dose.

Our study is the first study specifically designed to enrol only children with complicated, frequently relapsing, and steroid- and cyclosporine-dependent NS with normal basal IgG levels. Our case series shows that RTX can induce IgG hypogammaglobulinemia in patients with pre-RTX IgG normal values and that persisting post-RTX IgG hypogammaglobulinemia could be dose-dependent. None of the patients developing IgG hypogammaglobulinemia showed severe infections. Only one patient suffered from recurrent acute otitis media and underwent substitutive IgG infusion.

This article adds to our knowledge about the safety of RTX in children with complicated NS. Future studies should prospectively collect multicentre data on the effects of RTX on IgG levels and risk of severe infections. This will improve management of post-RTX IgG hy-pogammaglobulinemia and help define patients who could benefit from substitutive IgG infusion.

The authors thank Anna Carella for English language editing of this manuscript.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pedersen EB, Stavroulopoulos A, Tanaka H S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Iijima K, Sako M, Nozu K, Mori R, Tuchida N, Kamei K, Miura K, Aya K, Nakanishi K, Ohtomo Y, Takahashi S, Tanaka R, Kaito H, Nakamura H, Ishikura K, Ito S, Ohashi Y; Rituximab for Childhood-onset Refractory Nephrotic Syndrome (RCRNS) Study Group. Rituximab for childhood-onset, complicated, frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1273-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Marco H, Smith RM, Jones RB, Guerry MJ, Catapano F, Burns S, Chaudhry AN, Smith KG, Jayne DR. The effect of rituximab therapy on immunoglobulin levels in patients with multisystem autoimmune disease. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Roberts DM, Jones RB, Smith RM, Alberici F, Kumaratne DS, Burns S, Jayne DR. Rituximab-associated hypogammaglobulinemia: incidence, predictors and outcomes in patients with multi-system autoimmune disease. J Autoimmun. 2015;57:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Venhoff N, Effelsberg NM, Salzer U, Warnatz K, Peter HH, Lebrecht D, Schlesier M, Voll RE, Thiel J. Impact of rituximab on immunoglobulin concentrations and B cell numbers after cyclophosphamide treatment in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitides. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Delbe-Bertin L, Aoun B, Tudorache E, Lapillone H, Ulinski T. Does rituximab induce hypogammaglobulinemia in patients with paediatric idiopathic nephrotic syndrome? Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:447-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fujinaga S, Ozawa K, Sakuraya K, Yamada A, Shimizu T. Late-onset adverse events after a single dose of rituximab in children with complicated steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Clin Nephrol. 2016;85:340-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Guigonis V, Dallocchio A, Baudouin V, Dehennault M, Hachon-Le Camus C, Afanetti M, Groothoff J, Llanas B, Niaudet P, Nivet H, Raynaud N, Taque S, Ronco P, Bouissou F. Rituximab treatment for severe steroid- or cyclosporine-dependent nephrotic syndrome: a multicentric series of 22 cases. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1269-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stiehm ER, Fudenberg HH. Serum levels of immune globulins in health and disease: a survey. Pediatrics. 1966;37:715-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Christou EAA, Giardino G, Worth A, Ladomenou F. Risk factors predisposing to the development of hypogammaglobulinemia and infections post-Rituximab. Int Rev Immunol. 2017;36:352-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |