Published online Apr 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i8.951

Peer-review started: December 20, 2018

First decision: January 12, 2019

Revised: February 15, 2019

Accepted: February 26, 2019

Article in press: February 26, 2019

Published online: April 26, 2019

Processing time: 127 Days and 18.4 Hours

Patients discharged after hospitalization for acute heart failure (AHF) are frequently readmitted due to an incomplete decongestion, which is difficult to assess clinically. Recently, it has been shown that the use of a highly sensitive, non-invasive device measuring lung impedance (LI) reduces hospitalizations for heart failure (HF); it has also been shown that this device reduces the cardiovascular and all-cause mortality of stable HF patients when used in long-term out-patient follow-ups. The aim of these case series is to demonstrate the potential additive role of non-invasive home LI monitoring in the early post-discharge period.

We present a case series of three patients who had performed daily LI measurements at home using the edema guard monitor (EGM) during 30 d after an episode of AHF. All patients had a history of chronic ischemic HF with a reduced ejection fraction and were hospitalized for 6–17 d. LI measurements were successfully made at home by patients with the help of their caregivers. The patients were carefully followed up by HF specialists who reacted to the values of LI measurements, blood pressure, heart rate and clinical symptoms. LI reduction was a more frequent trigger to medication adjustments compared to changes in symptoms or vital signs. Besides, LI dynamics closely tracked the use and dose of diuretics.

Our case series suggests non-invasive home LI monitoring with EGM to be a reliable and potentially useful tool for the early detection of congestion or dehydration and thus for the further successful stabilization of a HF patient after a worsening episode.

Core tip: The monitoring of lung impedance (LI) using the edema guard monitor (EGM) seems to be a very sensitive tool for detecting an early increase in lung fluid volume. Non-invasive daily monitoring of LI with the EGM consistently reflects the changes in the dose of diuretics and responds to other treatment adjustments. The titration of the diuretic dose, according to LI values, may optimize patient stabilization in the early post-discharge period.

- Citation: Lycholip E, Palevičiūtė E, Aamodt IT, Hellesø R, Lie I, Strömberg A, Jaarsma T, Čelutkienė J. Non-invasive home lung impedance monitoring in early post-acute heart failure discharge: Three case reports. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(8): 951-960

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i8/951.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i8.951

Hospital readmissions are a challenge in the care of heart failure (HF) patients. Readmissions are stressful for patients and families and, at the same time, might have financial consequences for health care organizations. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program was recently established in the United States. This program involved a public reporting of hospitals’ 30-d risk-standardized readmission rates and applied financial penalties for hospitals with higher readmissions. The results of such a health care policy show that focusing mainly on the financial part of health care may significantly worsen patient care and outcomes[1,2]. In the first 30 d, the patients seem to be most vulnerable for rehospitalization; therefore, extra attention during this time period is warranted.

The impedance-HF trial revealed that the use of lung impedance (LI) mea-surements for the guidance of the preemptive treatment of patients with chronic HF reduced all-cause and HF hospitalizations by 39% and 55%, respectively[3]. In that study, measurements of LI were done using the highly sensitive, non-invasive device edema guard monitor (EGM). The EGM is based on an algorithm calculating the chest wall impedance, which is the preponderant component of the total electrical thoracic impedance. The subtraction of the chest wall impedance from the latter yields the net LI, which is the impedance of interest. Decreasing LI values represent the increase of lung fluid[1]. In previous reports, EGM was used only in the hospital or during regular outpatient clinic visits. Since EGM seems to be very sensitive to evolving pulmonary congestion, we hypothesized that it could be an accurate tool for the cautious titration of the doses of medicines, especially diuretics, ensuring a smooth and swift transition to follow-up care[3,4].

We present a case series of three patients after an episode of acute heart failure (AHF), who had autonomously performed daily home LI measurements using the EGM during a 1-month follow up period. The aim of this case series is to demonstrate the potential additive role of non-invasive LI monitoring with EGM in patient stabilization in the early post-discharge period.

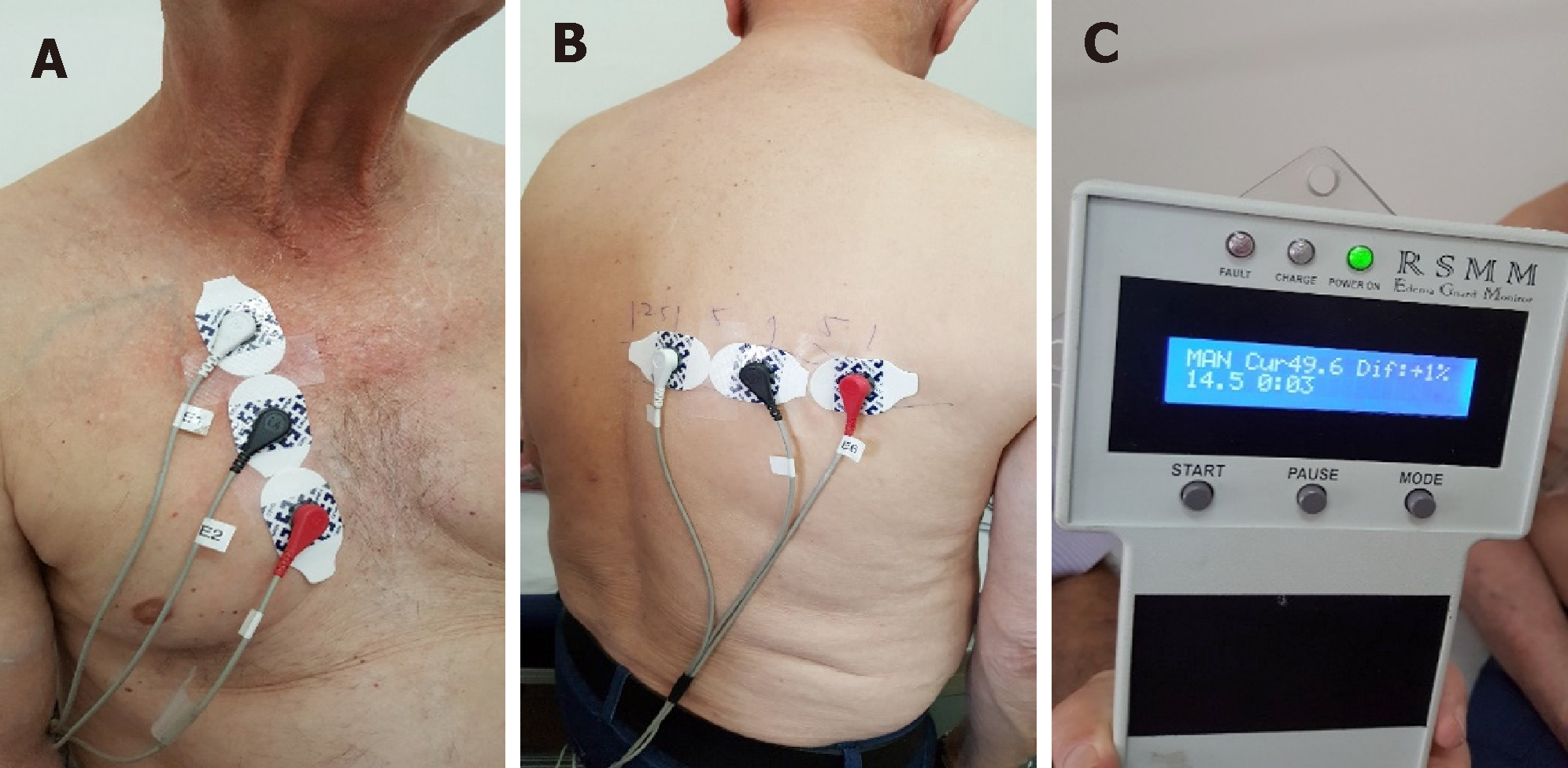

The measurements were done with the help of the patients’ caregivers once every day at the same time, attaching three EGM electrodes on the front and three EGM electrodes on back side of the chest wall, repeating the measurements 3 times (Figure 1). The LI values were being daily reported to a HF nurse via phone call or SMS, along with arterial blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR) and body weight. Two patients performed all 30 measurements (100%) and one 29 d out of 30 (96.7%). Echo-cardiography and laboratory tests were performed before discharge and 1 month later.

We present three patients suffering from ischemic HF with a reduced ejection fraction, who were urgently hospitalized because of signs and symptoms of decompensation.

At admission patients complained of progressing AHF symptoms: dyspnea at mild physical exertion or at rest, fatigue, palpitations and dizziness.

All patients had a history of chronic ischemic HF with a reduced ejection fraction for several years.

Patients’ past illnesses are shown in Table 1.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

| Age | 66 | 62 | 83 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female |

| Medical history | |||

| Arterial hypertension | + | + | + |

| Kidney disease | + | + | + |

| Myocardial infarction | + | + | + |

| Revascularization | + | + | + |

| Atrial fibrillation | - | + | - |

| Implanted devices | Biventricular pacemaker | Biventricular defibrillator | - |

| Length of stay (d) | 6 | 17 | 15 |

Patients’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1; family history was unremarkable.

At admission physical examination of the patients revealed normal BP, tachycardia, leg edema, fine crackles in the lungs. In Patient 2 several paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia were seen on electrocardiogram, led by cold sweat, extreme weakness and decrease of BP.

Laboratory tests parameters are summarized in Table 2.

| Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |||

| Discharge | After 30 d | Discharge | After 30 d | Discharge | After 30 d | |

| Laboratory tests | ||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 109 | 179 | 3485 | 2061 | 2927 | 5398 |

| Troponin I (ng/L) | 13.5 | 15.4 | 50.2 | 20.8 | 168.0 | 25.1 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.2 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 4.2 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 | 138 | 139 | 139 | 137 | 143 |

| Chlorine (mmol/L) | 100 | 95 | 101 | 98 | 98 | 103 |

| Creatinine (mkmol/L) | 133 | 282 | 96 | 103 | 111 | 118 |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) | 48 | 19 | 73 | 68 | 40 | 37 |

| Echocardiography | ||||||

| LV diastolic diameter (mm) | 59 | 56 | 76 | 76 | 71 | 71 |

| LV ejection fraction 2D (%) | 29 | 27 | 20 | 28 | 23 | 30 |

| LV ejection fraction 3D (%) | 26 | 29 | 19 | 25 | 35 | 23 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) 2D | 3.1 | 3.43 | 4.14 | 4.68 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) 3D | 1.7 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 4 | 4.3 | 2.2 |

| LV stroke volume 2D (mL) | 36 | 47 | 41 | 52 | 48 | 58 |

| PCWP (by Nagueh, mmHg) | 9.34 | 12.7 | 21.0 | 17 | 13.0 | 8.2 |

| Global longitudinal 2D strain (%) | -7 | -8.8 | -6 | -3.6 | -6.2 | -7.7 |

| Right ventricular diameter (cm) | 3.3 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 2.3 | 1.9 |

| RV S’ (cm/s) | 9 | 11 | 7 | 10 | 15 | 14 |

| TAPSE (cm) | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| RV FAC (%) | 32.3 | 35 | 16.6 | 28.8 | 49.6 | 74.8 |

| Lung impedance (Ω) | 88.6 | 93.0 | 107.9 | 97.1 | 101.8 | 88.1 |

| Weight (kg) | 80 | 81.3 | 104 | 105 | 60.0 | 61.8 |

| Medicatio | ||||||

| Percentage of target dose of beta-blocker | 25% | 50 % | 100 % | 100% | 25% | 25% |

| Percentage of target dose of ACEI | 100% | 100% | 12.5% | 25% | 50% | 25% |

| Percentage of target dose of Spironolactone | 50% | - | 50% | 100% | 100% | - |

| Torasemide daily dose (mg) | 50 mg (e.s.d.) | 10 mg | 50 mg | 100 mg | 25 mg | 10 mg |

Echocardiographic parameters are shown in Table 2.

Based on clinical symptoms, signs and objective findings, acute decompensated HF was diagnosed in all patients.

During hospitalization, patients were treated medically according to the ESC guidelines (Table 2). In Patient 2, several paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia were documented with a subsequent implantation of a biventricular defibrillator; Patient 3 was additionally treated with an implantation of drug-eluting stents in the left main and 2 other coronary arteries. Given the severe systolic dysfunction, mitral regurgitation, pulmonary hypertension and anticipated long duration of stenting, coronary intervention in Patient 3 was protected with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The dynamics of laboratory, echocardiographic parameters, LI, weight and discharge HF medications are presented in Table 2.

During the course of 30 d follow-up in all three patients, the dosages of medications were adjusted remotely with telephone calls or during four unplanned visits to the outpatient department.

The patients were asked to come for additional assessments due to deteriorating symptoms, and for laboratory assessments when an electrolyte imbalance or a worsening renal function were suspected. All patients were discharged in a better functional status, but they still remained in functional class III per the New York Heart Association classification.

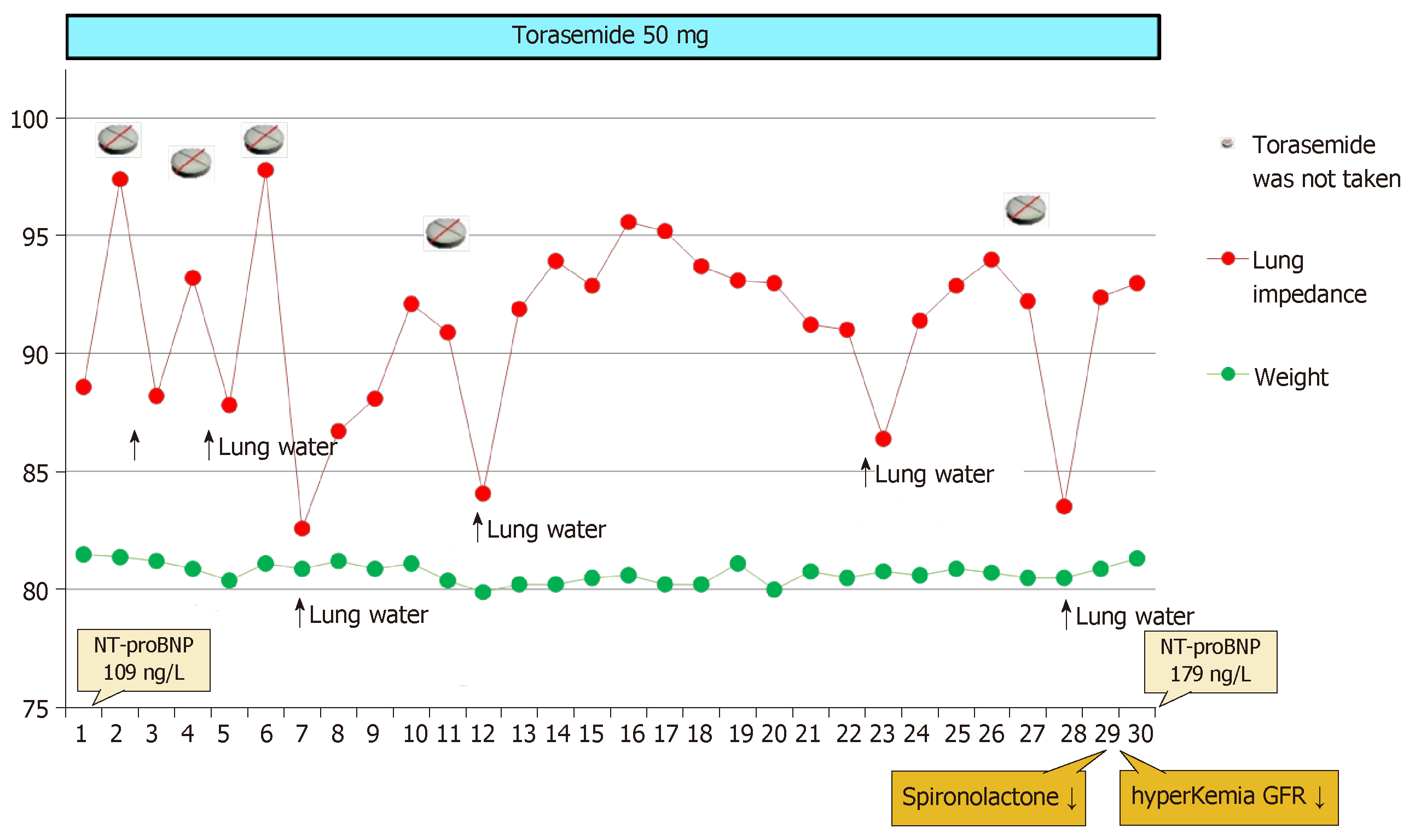

Torasemide 50 mg was prescribed in Patient 1 every other day during the first week. There were 5 d when the patient did not take torasemide at all. Figure 1 illustrates the high dependence of the LI value on the use of a diuretic: each missed diuretic dose has caused the mean drop of LI value by 9 points, or 9.5% (maximal LI value was 97.8 Ω, minimal 82.6 Ω). The concomitant fluctuation of the patient’s weight was negligible, ranging between 0 and 500 g, mostly decreasing (Figure 2).

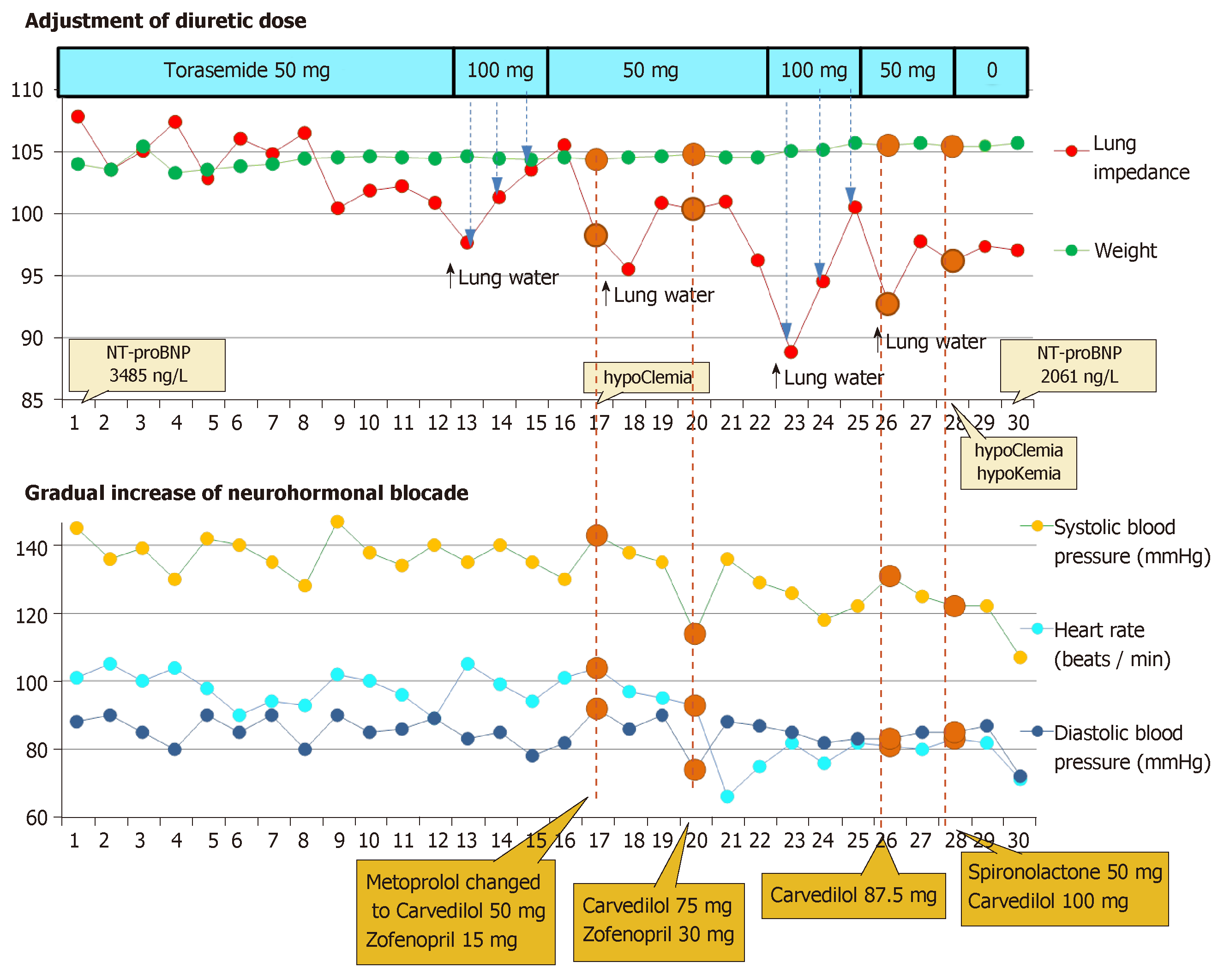

For Patient 2, the decrease of LI by -9% and -18%, compared with the initial LI, was twice treated by increasing the dose of torasemide from 50 to 100 mg daily. During the follow-up period, the Patient 2’s weight fluctuated between 103.3 to 105.7 kg. In 4 d, when LI had decreased the most, the patient’s weight increased by 200 g (0.2%) averagely, as compared with the previous day (Figure 3).

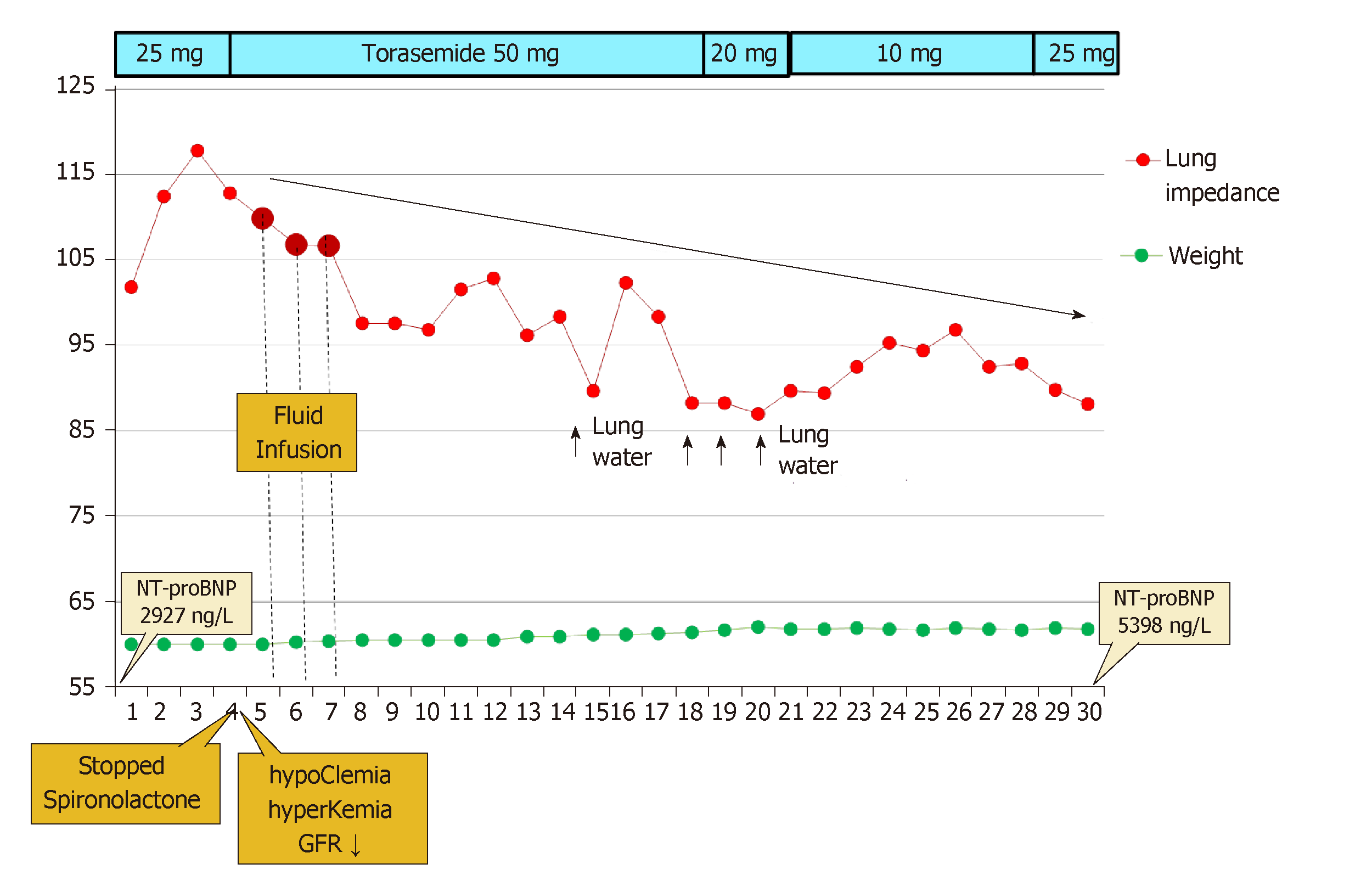

In Patient 3, the LI value at discharge was 101.8 Ω, while during the next 3 d, it was high and still increasing (101- > 112- > 117Ω; +15%), pointing to decreasing lung fluid, yet the patient felt poorly. The patient reported a shortness of breath at rest and during night. On the 4th d, the patient was invited to an unscheduled cardiologist visit; acute renal failure with hyperkalemia and hypochloremia were diagnosed. The patient was readmitted for 3 d and treated with intravenous fluid and electrolyte infusion. An acute kidney injury was likely associated with contrast-induced damage after the complex percutaneous coronary procedure. Subsequently, during a three-day period (from the 17th to the 20th of the month), Patient 3 gained 800 g in weight, felt increased dyspnea on the 20th and 21st d in parallel with a decrease of LI. The negative dynamics of NT-proBNP on the 30th d were concordant with a gradual progressive decline of LI during the follow-up (Figure 4).

In Patient 1 and Patient 3, clinically relevant inverse correlations (a decrease of LI and an increase in weight) were found. LI had decreased 1 d before the increase of weight of Patient 1 with a cross-correlation coefficient equal to -0.738 (P < 0.001); in Patient 3, LI and weight has had the maximum cross-correlation at the same day with a coefficient of -0.830 (P < 0.001).

In the course of a 30 d-follow-up, the dosages of medications were adjusted remotely via telephone calls reacting to the changes in symptoms, BP, HR or LI in all three patients. The patients were asked to come for four unplanned visits to the outpatient department when the symptoms had been deteriorating, LI had decreased but an electrolyte imbalance or a worsening renal function had been concomitantly suspected. Among other clinical parameters, the values of LI were the main triggers for adjusting treatment, especially for the dosage of diuretics (Table 3).

| Trigger | Intervention | Frequency of intervention, times |

| Symptoms (weakness) | Hospitalization because of revealed renal failure, hyperkalemia | 1 |

| High HR | Increasing the dose of beta-blockers | 3 |

| Administration of Ivabradine | 1 | |

| Uncontrolled BP | Increasing the dose of ACE inhibitors | 1 |

| Electrolyte imbalance | Increasing the dose of Spironolactone and decreasing the dose of Torasemide | 1 |

| LI decrease | Increasing the dose of beta-blockers and Spironolactone | 1 |

| Increasing the dose of ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers | 1 | |

| Increasing the dose of Torasemide | 5 | |

| Weight gain | - | 0 |

A variety of tools that quantify changes in lung fluid content have been evaluated to aid in the early detection of impending HF exacerbation, but in clinical practice, the prediction of pulmonary congestion is still a challenge. Invasive hemodynamic monitoring of PA pressure using a permanently implanted pressure sensor and the titration of diuretics according to pressure values have been reported to decrease hospitalizations for acute HF during 6 mo[5]. Monitoring of LI is also possible through the use of OptiVol feature and implanted cardioverter defibrillator or biventricular pacemaker.Although adding OptiVol alerts to HF management in observational studies was shown to improve patient prognosis as well, the positive predictive value for HF exacerbations was found to be only moderate[6,7].

The main disadavantages of these techniques are invasiveness, relatively high cost and inapplicability on a routine basis. Non-invasive transthoracic impedance (TI) measurements are associated with chest congestion, as fluid increases the electrical conductivity of the tissue[8,9]. The use of conventional electrical TI equipment for monitoring pulmonary congestion was found to be insufficiently sensitive and did not guarantee reliable monitoring of lung fluid content in the individual patient[10]. This may be explained by the fact that TI consists of the target net LI, which is only a small fraction of the overall TI, plus the high impedance of the chest walls.

In this case series, we report three patients with acute HF, who were monitored with the help of the EGM – a highly sensitive, non–invasive, LI measuring device. An arrangement of three electrodes on each side of the chest allows additional electrical circuits between electrodes, which enables calculation of the chest wall impedance and its subtraction from TI; this approach increases the sensitivity of the device to measure changes in lung fluid content by approximately 25 times[3]. As a result, preemptive treatment of an evolving pulmonary congestion can be initiated very early, a therapeutic policy that has proven its effectiveness in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction[11]. Our experience with these patients suggests the EGM to be a practical tool that can be used for monitoring of lung fluid, especially while adjusting the dose of diuretics. We have applied a threshold of approximately 10% for reduction of LI (from the initial value measured on discharge) for therapy adjustment. This value is based on previous publications showing the LI dynamics during HF hospitalization and our own experience[12,13] The presented example of Patient 1 clearly illustrates a high dependence of the LI value on the use of diuretics, reflecting an increase in congestion following after the day when the medication was not taken.

Importantly, the measurement of LI with the EGM at home requires the help of a caregiver to attach electrodes to the chest. Though not technically difficult, this dependence on family members may be considered a disadvantage of the method. An essential aspect is the availability of healthcare professional who daily accepts and reacts to LI values. Considering data on reduction of HF hospitalizations using this kind of congestion monitoring[3], financial savings with EGM may be highly significant due to the relatively low cost of the device and regular service.

Significant fluctuations of LI were noticed in all these cases; moreover, the LI change was the most important trigger for medication adjustment compared to standard monitoring variables, such as BP, HR, symptoms and markers of renal function. Though the monitoring of weight changes caused by fluid retention is routinely recommended for HF patients[13], several studies showed that many episodes of worsening HF did not appear to be associated with weight gain. For example, in a case-control study 54% of patients hospitalized due to AHF gained ≤ 1 kg during the month prior to admission[14]. This suggests that volume overload incompletely characterizes the pathophysiology of AHF and redistribution of volume may also contribute to the development of signs and symptoms of congestion[15,16].

These cases illustrate that LI measurements may represent a more sensitive method for the evaluation of fluid retention compared to weight and subjective symptoms. In two out of these three patients, we found a clinically and statistically significant correlation (lag -1; 0) of weight increase with the drop of LI. It was shown previously that the sensitivity of LI for HF hospitalization and the ambulatory adjustment of diuretics was twice as high as of body weight (83.3% vs 43.9%), and the unexplained detection rate per patient-year was 1.6 vs 4.8, respectively[17]. The case of Patient 3 illustrates that the LI measurements can sometimes even reflect excessive dehydration, assisting in the detection of not only an under- but also over-dosage of diuretics.

Our first experience with taking LI measurements using the EGM implies the high sensitivity and potential clinical utility of this tool consistently reflected the changes in the dose of diuretics. Non-invasive daily monitoring of LI may become an important component of successful transitions from acute to stable phases of HF, but more clinical experience is needed in order to find the best algorithms for the reactions of health care professionals to different LI changes.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Lithuania

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Iacoviello M, Rostagno C S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, Cox M, DeVore AD, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Matsouaka RA, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Association of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program Implementation With Readmission and Mortality Outcomes in Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:44-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 56.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Čerlinskaitė K, Hollinger A, Mebazaa A, Cinotti R. Finding the balance between costs and quality in heart failure: a global challenge. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:1175-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shochat MK, Shotan A, Blondheim DS, Kazatsker M, Dahan I, Asif A, Rozenman Y, Kleiner I, Weinstein JM, Frimerman A, Vasilenko L, Meisel SR. Non-Invasive Lung IMPEDANCE-Guided Preemptive Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial (IMPEDANCE-HF Trial). J Card Fail. 2016;22:713-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shochat M, Shotan A, Blondheim DS, Kazatsker M, Dahan I, Asif A, Shochat I, Frimerman A, Rozenman Y, Meisel SR. Derivation of baseline lung impedance in chronic heart failure patients: use for monitoring pulmonary congestion and predicting admissions for decompensation. J Clin Monit Comput. 2015;29:341-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, Aaron MF, Costanzo MR, Stevenson LW, Strickland W, Neelagaru S, Raval N, Krueger S, Weiner S, Shavelle D, Jeffries B, Yadav JS; CHAMPION Trial Study Group. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:658-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1216] [Article Influence: 86.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Catanzariti D, Lunati M, Landolina M, Zanotto G, Lonardi G, Iacopino S, Oliva F, Perego GB, Varbaro A, Denaro A, Valsecchi S, Vergara G; Italian Clinical Service Optivol-CRT Group. Monitoring intrathoracic impedance with an implantable defibrillator reduces hospitalizations in patients with heart failure. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32:363-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Conraads VM, Tavazzi L, Santini M, Oliva F, Gerritse B, Yu CM, Cowie MR. Sensitivity and positive predictive value of implantable intrathoracic impedance monitoring as a predictor of heart failure hospitalizations: the SENSE-HF trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2266-2273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Larsen FF, Mogensen L, Tedner B. Transthoracic electrical impedance at 1 and 100 kHz--a means for separating thoracic fluid compartments? Clin Physiol. 1987;7:105-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cuba-Gyllensten I, Gastelurrutia P, Riistama J, Aarts R, Nuñez J, Lupon J, Bayes-Genis A. A novel wearable vest for tracking pulmonary congestion in acutely decompensated heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:199-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Packer M, Abraham WT, Mehra MR, Yancy CW, Lawless CE, Mitchell JE, Smart FW, Bijou R, O'Connor CM, Massie BM, Pina IL, Greenberg BH, Young JB, Fishbein DP, Hauptman PJ, Bourge RC, Strobeck JE, Murali S, Schocken D, Teerlink JR, Levy WC, Trupp RJ, Silver MA; Prospective Evaluation and Identification of Cardiac Decompensation by ICG Test (PREDICT) Study Investigators and Coordinators. Utility of impedance cardiography for the identification of short-term risk of clinical decompensation in stable patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2245-2252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shochat M, Shotan A, Blondheim DS, Kazatsker M, Dahan I, Asif A, Shochat I, Rabinovich P, Rozenman Y, Meisel SR. Usefulness of lung impedance-guided pre-emptive therapy to prevent pulmonary edema during ST-elevation myocardial infarction and to improve long-term outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:190-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lycholip E, Čelutkienė J. Doctoral dissertation: Telemonitoring technologies for heart failure patients: opinions of professionals, patient-reported outcomes and measurements of lung impedance. 2018: 46-49. Available from: http://www.lmb.lt/nr-36-spalio-1-7-d/. |

| 13. | Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; Authors/Task Force Members; Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4368] [Cited by in RCA: 4909] [Article Influence: 545.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 14. | Mullens W, Damman K, Harjola VP, Mebazaa A, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Martens P, Testani JM, Tang WHW, Orso F, Rossignol P, Metra M, Filippatos G, Seferovic PM, Ruschitzka F, Coats AJ. The use of diuretics in heart failure with congestion - a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:137-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 690] [Article Influence: 115.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dovancescu S, Pellicori P, Mabote T, Torabi A, Clark AL, Cleland JGF. The effects of short-term omission of daily medication on the pathophysiology of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chaudhry SI, Wang Y, Concato J, Gill TM, Krumholz HM. Patterns of weight change preceding hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:1549-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Al-Chekakie MO, Bao H, Jones PW, Stein KM, Marzec L, Varosy PD, Masoudi FA, Curtis JP, Akar JG. Addition of Blood Pressure and Weight Transmissions to Standard Remote Monitoring of Implantable Defibrillators and its Association with Mortality and Rehospitalization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |