Published online Mar 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i6.759

Peer-review started: December 12, 2018

First decision: January 5, 2019

Revised: January 21, 2019

Accepted: January 29, 2019

Article in press: January 30, 2019

Published online: March 26, 2019

Processing time: 104 Days and 20 Hours

Aeromonas species are uncommon pathogens in biliary sepsis and cause substantial mortality in patients with impaired hepatobiliary function. Asia has the highest incidence of infection from Aeromonas, whereas cases in the west are rare.

We report the case of a 64-year-old woman with advanced pancreatic cancer and jaundice who manifested fever, abdominal pain, severe thrombocytopenia, anemia and kidney failure following the insertion of a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Blood culture results revealed the presence of Aeromonas veronii biovar veronii (A. veronii biovar veronii). After antibiotic therapy and transfusions, the life-threatening clinical conditions of the patient improved and she was discharged.

This was a rare case of infection, probably the first to be reported in West countries, caused by A. veronii biovar veronii following biliary drainage. A finding of Aeromonas must alert clinician to the possibility of severe sepsis.

Core tip:Aeromonas infection is fairly infrequent, and cholangitis caused by this species represents around 3% of all cases of bile duct infection. The bacterium appears to have high incidence in Asia. The infection may have a dramatic presentation. Our case report describes one of the few cases of cholangitis by Aeromonas to be reported in Western countries and, in particular, the first to be attributed to Aeromonas veronii biovar veronii after the positioning of biliary drainage. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered a priori. The finding of an infection from Aeromonas should alert the clinician to the possibility of severe sepsis.

- Citation: Monti M, Torri A, Amadori E, Rossi A, Bartolini G, Casadei C, Frassineti GL. Aeromonas veronii biovar veronii and sepsis-infrequent complication of biliary drainage placement: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(6): 759-764

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i6/759.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i6.759

Aeromonas species are small, ubiquitous gram-negative bacilli isolated from a variety of environmental sources including water, seafood, meat and vegetables, and occasionally from the feces of healthy individuals. A review by Janda and Abbot[1] listed 21 published Aeromonas species. This bacterium is a potential pathogen in gastroenteritis and in a wide spectrum of extraintestinal infections, including wound infection pneumonia, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), peritonitis, biliary sepsis and septicemia[2]. Aeromonas plays an important role in biliary duct infection in South East Asia because recurrent pyogenic cholangitis is prevalent in this region. The condition is characterized by multiple intrahepatic bile duct stones, strictures and dilations and recurrent attacks of septicemia. The consumption of raw seafood contaminated by the Aeromonas species may also contribute to the development of septicemia. Aeromonas, although not a common pathogen in biliary sepsis, has an overall mortality rate of 25% to 75%[3]. According to some case reports, this species causes around 3% of all cases of cholangitis in Asia[4] and even fewer cases in the Western world. We describe a case of severe sepsis from Aeromonas veronii biovar veronii (A. veronii biovar veronii) following biliary drainage in an Italian patient with advanced pancreatic cancer.

In August 2017 a 64-year-old Caucasian woman was urgently admitted to the Oncology Ward of our institute with jaundice. She had also been suffering from increasing dyspepsia and asthenia for the previous few weeks.

In August 2013 the patient had undergone pancreaticoduodenectomy and cholecystectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma with positive surgical margins. Between May 2014 and July 2017, she underwent three lines of palliative chemotherapy.

Her personal and family history did not reveal anything significant.

Physical examination upon admission was unremarkable except for jaundice.

Laboratory exams showed a white blood cell count of 8.51 × 109/L (reference range 4.0-10.0) with 74.3% neutrophils, 17.4% lymphocytes and 7.6% monocytes. Hemoglobin was 11.9 g/dL (12-15.5) and platelets 374 × 109/L (140-400). The prothrombin time (international normalized ratio, INR) was 1.31 (0.80-1.20) and the activated partial thromboplastin time ratio was 0.94 (0.8-1.2). Electrolyte and renal function tests were normal. In particular, creatinine was 0.73 mg/dL (0.5-1.0) and velocity of glomerular filtration (eGFR) was 87 mL/min/1.73m2, while protein C reaction (PCR) was 509 mg/dL (< 5.0). Conversely, total bilirubin was 16.39 mg/dL (< 1.20), direct bilirubin 13.61 mg/dL (< 0.30), aspartate transaminase 183 U/L (< 32), alanine transaminase 169 U/L (< 33), alkaline phosphatase 543 U/L (35-104), gammaGT 1019 (5-36) and lactate dehydrogenase 247 U/L (135-214). Tests for hepatitis B and C were negative, as was rectal screening for multiresistant gram-negative bacteria performed as a precautionary measure when the patient was admitted.

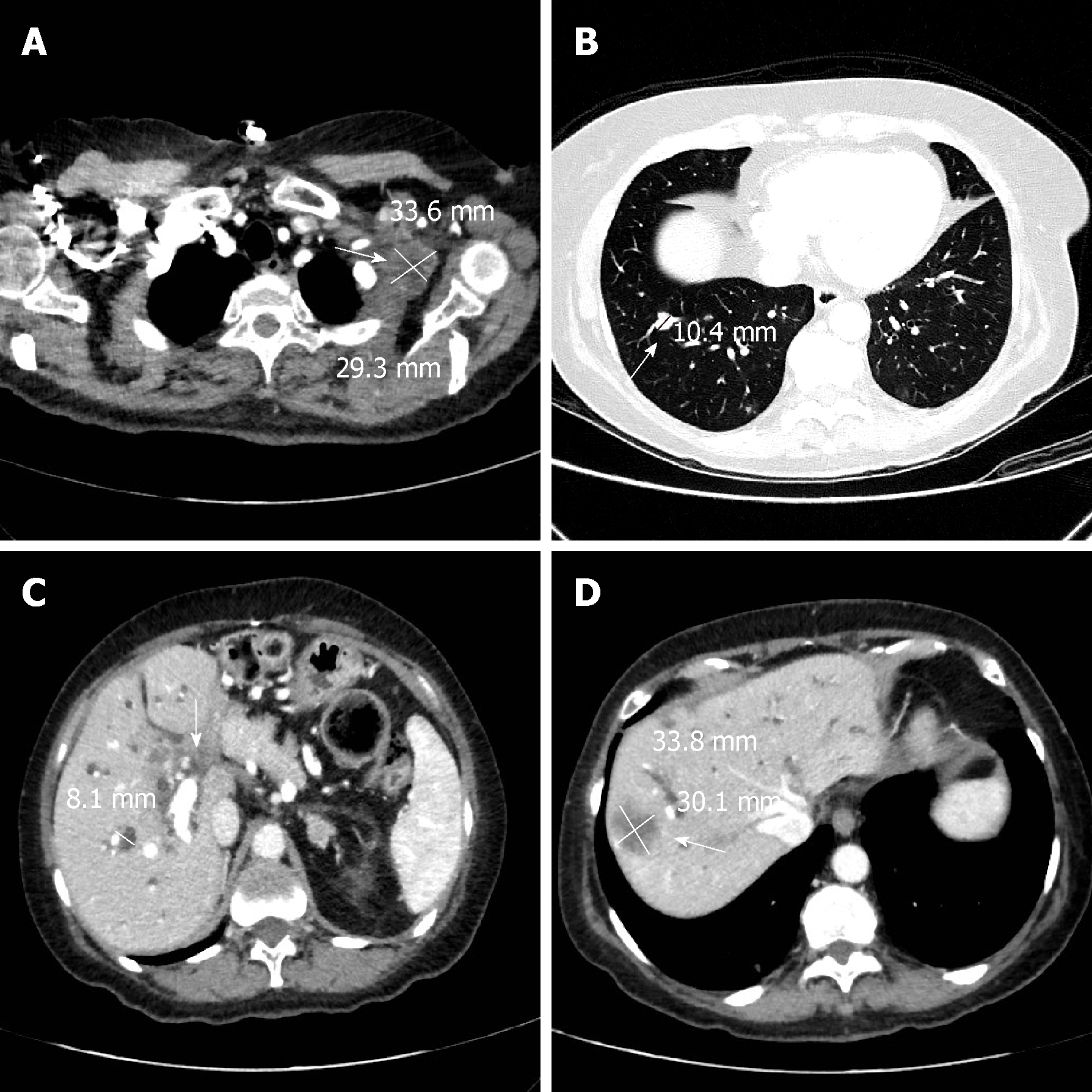

A total body computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the metastases in the lungs, chest, abdominal lymph nodes, liver and hepatic hilar area (Figure 1). There was also marked ectasia of the intrahepatic bile ducts of both hemisystems. Six d after admission the patient underwent difficult placement of a percutaneous transhepatic external biliary catheter in the left hemisystem. A week later the catheter was checked for leakage because total bilirubin had not fallen below 11.8 mg/dL and was found to have become dislodged from the liver. The procedure was repeated and a new internal-external device was inserted. The following day the patient experienced severe abdominal pain, in particular in the upper right quadrant, with negative Blumberg’s and positive Murphy’s signs. An abdominal CT scan excluded acute radiological or surgical complications. The patient also had an isolated episode of fever (38.2 °C), and complained of left chest pain. She felt restless but fatigued at the same time, and there was an evident worsening of her clinical conditions. Blood cultures were performed on blood drawn from the peripheral and central venous catheters. The patient was immediately given paracetamol 1000 mg and started empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy with levofloxacin 500 mg/d for five d. Intravenous fluids were increased to 1500 mL/d. The following day oral steroid therapy with prednisone 25 mg was substituted with intravenous dexamethasone 8 mg. Two d after the insertion of the new catheter, hemoglobin was 10.5 g/dL, white blood cell count 13.65 × 109/L, platelets 29 × 109/L, creatinine 1.93 mg/dL and eGFR 27 mL/min/1.73/m2. The clinical chemistry laboratory noted that the creatinine value of 1.93 mg/dL was probably underestimated because of the presence of jaundice. The next day hemoglobin was 10.6 g/dL, white blood cell count 9.13 × 109/L, platelets 14 × 109/L, creatinine 1.11 mg/dL and eGFR 52 mL/min/1.73m2. Given the worsening thrombocytopenia, the patient received a pool of platelets and, when the blood culture results revealed the presence of A. veronii biovar veronii [sensitive to amikacin, minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) ≤ 2; cefotaxime, MIC ≤ 1; ceftazidime, MIC ≤ 1; gentamycin, MIC ≤ 1; and ciprofloxacin, MIC ≤ 0.25], moderately sensitive to imipenem and piperacillin/tazobactam, and resistant to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid], levofloxacin was replaced with ceftazidime 2 g three times/d. We excluded disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) because the INR was 1.21 (0.8-1.2), fibrinogen 846 mg/dL (150-400), D-dimer 536 μg/L (cut-off for thrombosis 200 μg/L) and antithrombin 91% (70-150) while PCR was 84 mg/dL. A cytomegalovirus blood test was < 120 IU/mL and thus considered negative, while second-level hematochemical exams revealed anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, slight erythrocyte fragmentation and some myelocytes. Frequent blood tests were performed to exclude DIC. The number of platelets progressively increased but hemoglobin decreased to 7.7 g/dL and Coombs test was negative. The patient thus received a blood transfusion. Total bilirubin decreased to 7.61 mg/dL and the patient’s performance status gradually improved.

The patient with advanced pancreatic cancer and biliary obstruction developed sepsis caused by A. veronii biovar veronii.

The patient with sepsis was treated with antibiotic therapy, first with levofloxacin then with ceftazidime and platelet and blood transfusions.

The patient was discharged in stable conditions after 10 d of ceftazidime to continue the best supportive care at home, including a further 4 d of the antibiotic therapy. The patient was alive at a distance of one mo from discharge but then was lost to follow-up.

Of the numerous Aeromonas species, few have been related unquestionably to human extraintestinal infections[5] by virtue of their isolation in pure culture from sterile sites. Sepsis is perhaps the most relevant Aeromonas infection in terms of severity and frequency and is associated predominantly with several underlying diseases. Individuals with hepatobiliary diseases are particularly susceptible to the infections[6,7]. In patients with hematologic diseases or solid tumors, antineoplastic drugs may induce alteration of gastrointestinal mucosa and allow transmigration of colonized Aeromonas species from the bowel into the circulatory system[8]. The role of A. veronii biovar veronii in human sepsis has been described very rarely. Abbott et al[9] reported the first case of A. veronii biovar veronii sepsis in an elderly man with advanced colorectal cancer who developed jaundice. The patient had multisystem organ failure two d after admission and died. In a subsequent report[10], A. veronii biovar veronii was responsible for bacteraemia and necrotizing fasciitis in a diabetic patient also affected by a Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria urinary tract infection. The potential portals of entry for Aeromonas bacteria are the gastrointestinal tract, skin lesions, previous surgery or local trauma in an aqueous environment. The pathogenic mechanism of Aeromonas is multifactorial because many virulence factors are involved, including the production of cytotoxins. These toxins can cause diarrhea[11] or hemorrhagic colitis, and may play a role in HUS[12]. In our patient, the A. veronii biovar veronii infection was responsible for monomicrobic cholangitis and was probably caused by the insertion of a percutaneous transhepatic biliary catheter. Few cases of sepsis from Aeromonas have been described in Western countries. Dryden and Munro[13] described 13 cases of Aeromonas-related septicemia (10 from Aeromonas sobria and 3 from Aeromonas hydrophila), some of which had biliary tract as the primary site of infection. In the United States, Clark and Chenoweth[14] reported 15 cases of Aeromonas infection of the hepatobiliary system but none were related to A. veronii biovar veronii. In France, Doudier et al[15] described 2 cases of septicemia caused by Aeromonas cavie and Aeromonas hydrophila following the placement of transhepatic biliary drainage.

Of note, the routine prophylaxis with ampicillin-sulbactam (or clindamycin and gentamycin for penicillin-allergic patients) before the percutaneous biliary drainage procedure was not done in our patient, an oversight on our part. The patient did not recall having had any contact with potentially contaminated water or food products before admission to hospital, she had not traveled abroad in the recent past, and there were no other cases of this infection in the hospital. The rapid manifestation of symptoms after the second drainage would thus seem to indicate a correlation with the invasive procedure.

The abdominal pain, fever and laboratory alterations in our patient were attributable to sepsis. Although highly improbable, we also considered HUS in the differential diagnosis. Only a few cases of HUS from Aeromonas have been described worldwide, with diarrhea as the common feature and sometimes the need for dialysis or hemofiltration. We were unable to confirm or refute HUS because specific laboratory tests for the condition such as polymerase chain reaction assay for shiga-like toxin genes and verotoxin test were not routinely performed.

Patients with Aeromonas are susceptible to aminoglycosides, quinolones, co-trimoxazole and aztreonam, but are resistant to broad-spectrum cephalosporins because Aeromonas has a propensity to produce at least 3 β-lactamases[1]. We initially used levofloxacin because the patient recalled having had a positive allergic reaction to an antibiotic in the past but could not remember its name. However, she had previously taken levofloxacin without problems. In our case Aeromonas veronii was resistant to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and moderately sensitive to imipenem. Of note, Sánchez-Céspedes[16] reported a resistance to imipenem in case of Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria, which should alert clinicians to the possible emergence of multidrug-resistance.

We describe a case of monomicrobic infection, cholangitis and sepsis caused by A. veronii biovar veronii, a rare event in humans. In fact, as far as we know, this is the first reported case of sepsis from A. veronii biovar veronii following biliary drainage in Western countries. It seems logical to hypothesize that the Aeromonas infection in our patient was related to the invasive biliary tract procedure which may have facilitated an ascending infection from intestinal bacteria. Our findings confirm the sensitivity of the bacterium to third-generation cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, quinolones, but the moderate sensitivity to imipenem and piperacillin/tazobactam is potentially indicative of future resistance to these antibiotics.

Our study highlights that Aeromonas infection can lead to life-threatening clinical conditions and significant laboratory alterations. Biliary drainage can cause cholangitis and antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended a priori for this surgical maneuver. The presence of an infection from Aeromonas should also alert clinicians to the possibility of severe sepsis.

The authors thank Gráinne Tierney and Cristiano Verna editorial assistance.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kai K, Rong GH, Sergi C S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Aeromonas: Taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:35-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1133] [Cited by in RCA: 1204] [Article Influence: 80.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Janda JM, Guthertz LS, Kokka RP, Shimada T. Aeromonas species in septicemia: Laboratory characteristics and clinical observations. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ko WC, Chuang YC. Aeromonas bacteremia: Review of 59 episodes. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1298-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chan FK, Ching JY, Ling TK, Chung SC, Sung JJ. Aeromonas infection in acute suppurative cholangitis: Review of 30 cases. J Infect. 2000;40:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Janda JM, Abbott SL. Evolving concepts regarding the genus Aeromonas: An expanding Panorama of species, disease presentations, and unanswered questions. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:332-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Serra N, Di Carlo P, Gulotta G, d' Arpa F, Giammanco A, Colomba C, Melfa G, Fasciana T, Sergi C. Bactibilia in women affected with diseases of the biliary tract and pancreas. A STROBE guidelines-adherent cross-sectional study in Southern Italy. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67:1090-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Igbinosa IH, Igumbor EU, Aghdasi F, Tom M, Okoh AI. Emerging Aeromonas species infections and their significance in public health. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:625023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ko WC, Lee HC, Chuang YC, Liu CC, Wu JJ. Clinical features and therapeutic implications of 104 episodes of monomicrobial Aeromonas bacteraemia. J Infect. 2000;40:267-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Abbott SL, Serve H, Janda JM. Case of Aeromonas veronii (DNA group 10) bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:3091-3092. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Hsueh PR, Teng LJ, Lee LN, Yang PC, Chen YC, Ho SW, Luh KT. Indwelling device-related and recurrent infections due to Aeromonas species. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:651-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sha J, Kozlova EV, Chopra AK. Role of various enterotoxins in Aeromonas hydrophila-induced gastroenteritis: Generation of enterotoxin gene-deficient mutants and evaluation of their enterotoxic activity. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1924-1935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Palma-Martínez I, Guerrero-Mandujano A, Ruiz-Ruiz MJ, Hernández-Cortez C, Molina-López J, Bocanegra-García V, Castro-Escarpulli G. Active Shiga-Like Toxin Produced by Some Aeromonas spp., Isolated in Mexico City. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dryden M, Munro R. Aeromonas septicemia: Relationship of species and clinical features. Pathology. 1989;21:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Clark NM, Chenoweth CE. Aeromonas infection of the hepatobiliary system: Report of 15 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:506-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Doudier B, Imbert G, Vitton V, Kahn M, La Scola B. Aeromonas septicaemia: An uncommon complication following placement of transhepatic biliary drainage devices in Europe. J Hosp Infect. 2006;62:115-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sánchez-Céspedes J, Figueras MJ, Aspiroz C, Aldea MJ, Toledo M, Alperí A, Marco F, Vila J. Development of imipenem resistance in an Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria clinical isolate recovered from a patient with cholangitis. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:451-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |