Published online Dec 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4384

Peer-review started: September 5, 2019

First decision: September 23, 2019

Revised: November 1, 2019

Accepted: November 23, 2019

Article in press: November 23, 2019

Published online: December 26, 2019

Processing time: 111 Days and 6.7 Hours

Spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (sOHSS) is extremely rare. It can be divided into four types according to its clinical manifestations and follicle stimulating hormone receptor mutations.

Here we report two cases of sOHSS in Chinese women, one with a singleton gestation developing sOHSS in the first trimester who conceived naturally and the other with a twin pregnancy developing sOHSS in the second trimester after a thawed embryo transfer cycle. Both patients were admitted to the hospital with abdominal distension, ascites, and enlarged ovaries. Conservative treatment was the primary option of management. The first patient had spontaneous onset labor at 40 wk of gestation and underwent an uncomplicated vaginal delivery of a male newborn. The second patient delivered a female baby and a male baby by caesarean section at 35 wk and 1 d of gestation.

Patients with a history of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome should be closely monitored. Single embryo transfer might reduce the risk of this rare syndrome.

Core tip: Spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (sOHSS) is extremely rare. It is always confused with ovarian tumors due to their similar symptoms. Here we report two cases of sOHSS, one woman with a singleton gestation developing sOHSS in the first trimester who conceived naturally and the other with a twin pregnancy in the second trimester after a thawed embryo transfer cycle. The first line investigation for the diagnosis is pelvic ultrasonography. Since sOHSS cannot be predicted, patients with a history of OHSS should be closely monitored. The primary management option is conservative therapy. Single embryo transfer may decrease the risk of developing severe OHSS in assisted reproductive cases.

- Citation: Gui J, Zhang J, Xu WM, Ming L. Spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: Report of two cases. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(24): 4384-4390

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i24/4384.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4384

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an iatrogenic potentially life-threatening disease, usually a complication during ovulation induction in in vitro fertilization embryo transfer. Risk factors for OHSS include young age, low body mass index, history of polycystic ovarian syndrome, history of previous OHSS, high level of anti-muller hormone (AMH), and higher doses of gonadotropins, etc. The pathogenesis of OHSS includes an increase in the permeability of the capillaries, resulting in a fluid shift from the intravascular space to the extravascular compartments, which is responsible for the development of ascites, sometimes pleural and/or pericardial effusion, hemoconcentration, oliguria, and electrolyte imbalance[1].

Spontaneous OHSS (sOHSS) has the similar clinical presentations as OHSS and is a rare event. During the past 30 years, sOHSS has been reported in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome[2], hypothyroidism[3], hydatidiform mole[4], invasive mole[5], gonadotropin-producing pituitary adenoma[6,7], multiple gestation[8], disturbed liver function[9], and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) gene mutation[10-13]. Previous studies have postulated that multiple pregnancy, gestational trophoblastic diseases, hypothyroidism, gonadotropin adenoma, and FSHR gene mutations are responsible for sOHSS[10]. In the present paper, we would report one case of sOHSS in a Chinese woman with a singleton gestation who conceived naturally, and another case of sOHSS with a twin pregnancy in the second trimester after a thawed embryo transfer cycle.

Case 1: A 23-year-old Chinese primigravida conceived spontaneously. She presented with complaints of abdominal distension, dyspnea, nausea, and vomiting.

Case 2: A 34-year-old nulligravida woman was admitted to our hospital complaining of abdominal distension, ascites, abruptly enlarged ovaries, and numbness in the right thigh.

Case 1: The patient’s symptoms started 2 d ago with abdominal distension, dyspnea, nausea, and vomiting.

Case 2: The symptoms started one week ago with abdominal distension, ascites, abruptly enlarged ovaries, and numbness in the right thigh.

Case 1: She had regular menstruation before her pregnancy and had no history of ovulation induction. She also denied the history of polycystic ovarian syndrome and hypothyroidism.

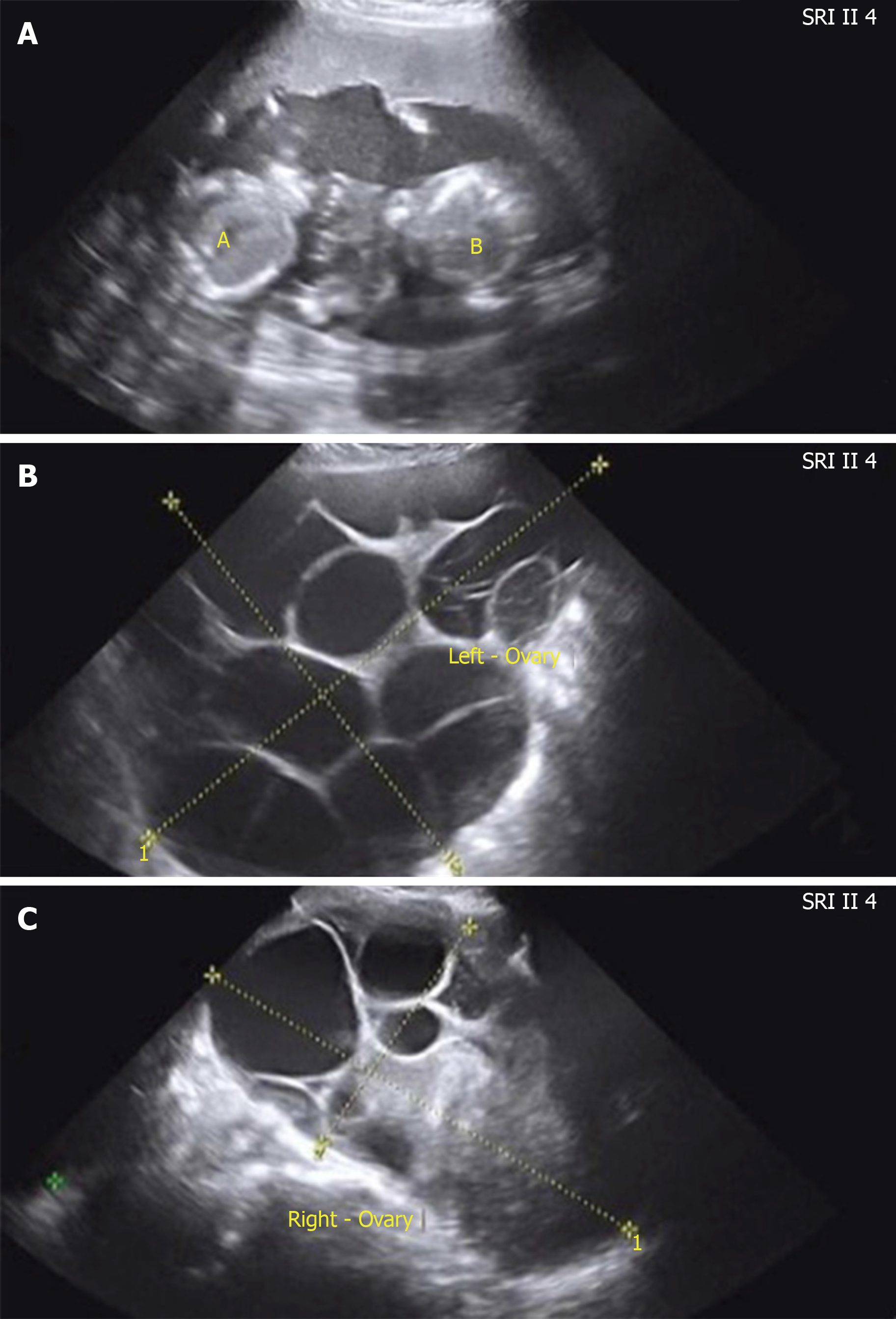

Case 2: She had regular menstruation and normal thyroid function. No previous history of illness or operation was noted. The 34-year-old nulligravida woman was referred to assisted reproductive technology due to azoospermatism of her husband. Super-long protocol was used for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. She was a hyper-reactive patient with a high level of AMH (7.97 ng/mL) and multiple antral follicle counts (more than 20). The starting dose of recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) was 125 IU. After 3 d, the dose was reduced to 112.5 IU because of her hyper-response. The total duration of stimulation was 9 d and then 9000 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) was used to trigger ovulation. Eighteen oocytes were retrieved. All embryos were frozen because of the high risk of OHSS (enlargement of the ovaries, left 9.2 cm × 6.6 cm, right 8.8 cm × 6.5 cm). Three months later, artificial hormone cycle was conducted to prepare frozen embryo transplantation. Oral estradiol valerate (4 mg/d for 7 d, then 6 mg/d) was used to prepare the endometrium. When the woman’s endometrial lining was 10 mm thick and estradiol was 104.5 pg/mL, two embryos were transferred into the uterine cavity 3 d following the start of progesterone administration. There was no follicular growth during this cycle. Twelve days after the embryo transfer, serum β-HCG level was 1389.9 IU/L. A viable twin pregnancy was confirmed by transvaginal ultrasonography 30 d after transplantation. During antenatal care, both ovaries abruptly became enlarged and ascites was observed by pelvic ultrasonography (left 28.46 cm × 12.36 cm, right 15.01 cm × 11.27 cm, ascites 2.95 cm) at the 17 wk of gestation (Figure 1A-C).

Case 1: After admission, her vital signs such as temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure were normal. Abdominal examination revealed a moderately distended, tender, and tense abdomen with positive shifting dullness on percussion.

Case 2: Her vital signs such as temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure were normal. Abdominal examination revealed a severely distended, tender, and tense abdomen.

Case 1: Laboratory studies showed normal levels of haemoglobin (121 g/L) and haematocrit (37.6%), decreased level of albumin (31.20 g/L, normal > 40 g/L), and increased values of β-HCG (>200000 IU/L) and CA125 (447.3 U/mL, normal < 35 U/mL), as well as slightly elevated liver enzymes, ketonuria (2+), and proteinuria (1+). Examinations regarding blood electrolytes, coagulation profile, renal function, thyroid function, blood glucose, carcinoembryonic antigen, and CA153 concentrations were unremarkable.

Case 2: Laboratory studies revealed the following findings: β-HCG 159226 IU/L, FSH 0.43 mIU/mL, luteinizing hormone (LH) 0.09 mIU/mL, human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) 74.30 pmol/L, AFP 158.70 ng/mL, and CA125 441.60 U/mL.

Case 1: Abdominal ultrasonographic examinations (Figures 2A-C) revealed a viable intrauterine pregnancy of a size consistent with dates, bilateral ovarian enlargement (the size of the left ovary was 14.92 cm × 7.98 cm and the size of the right ovary was 13.33 cm × 8.11 cm), massive ascites and bilateral cystic adnexal masses (left 4.91 cm × 4.33 cm, right 3.86 cm × 2.97 cm), and hepatolithiasis. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the chest disclosed right pleural effusion (4.8 cm).

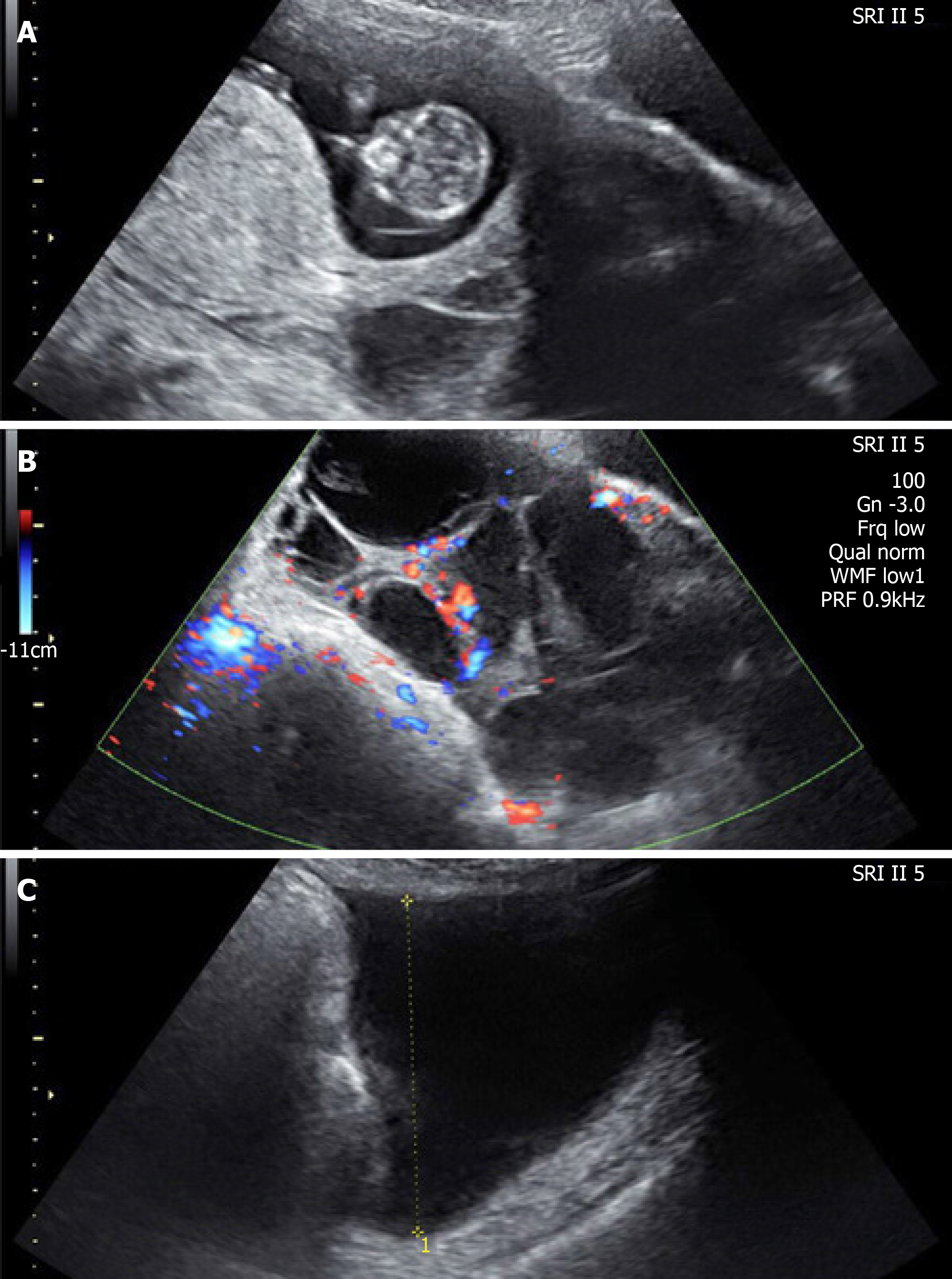

Case 2: Ultrasonography showed that there was a 4.9 cm pleural effusion in the left thorax and no abnormality was found in the kidneys or adrenal glands.

Case 2: Ovarian cyst puncture was performed, the fluid was macroscopically light yellow and clear, and a few mesenchymal cells and lymphocytes were observed under a microscope.

Due to the patient’s medical history and laboratory findings, a diagnosis of sOHSS was considered.

A provisional diagnosis of OHSS was made.

Pleural paracentesis was performed to aspirate 400-500 mL/d of pleural effusion to reduce the patient’s discomfort. She was admitted for monitoring and supportive therapy. She received complex conservative therapy at our ward, including intravenous fluid substitution with hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 sodium chloride and compound dextran 40 (both 500 mL/d), nutrition support, gastro- and hepato-protective therapy (rabeprazole sodium 40 mg/d and reduced glutathione 2.4 g/d) every day during hospitalization. She also received intravenous administration of human albumin at 100 mL/d for 3 d.

She received intravenous administration of colloid and albumin, and anti-inflammatory therapy.

The patient responded well to our treatment and was discharged 2 wk after admission. Her abdominal distension was relieved, and she had no dyspnea in the supine position, only with mild cough when she left the hospital. The pregnancy proceeded normally, and the patient had spontaneous onset labor at 40 wk of gestation and underwent an uncomplicated vaginal delivery of a male newborn.

After the treatment, her abdominal distension was relieved 10 d later. The volume of the ovaries was gradually reduced during the pregnancy. At 28 wk of gestation, the size of the left ovary was 10.5 cm × 6.3 cm, and the size of the right ovary was 11.5 cm × 7.9 cm. A caesarean section was performed at 35 wk and 1 d of gestation. Bilateral ovarian enlargement was noted (Figure 3). The pregnancy resulted in the live birth of a female baby weighing 2350 g, and a male baby weighing 2150 g.

sOHSS is extremely rare in the natural pregnancy or after thawed embryo transfer. Previous researchers have divided it into four subtypes according to its clinical manifestations and FSHR mutations[10]. Type I refers to the mutated FSHR cases with normal HCG, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and FSH levels, which can lead to recurrent sOHSS. Several kinds of FSHR gene mutations have been identified, such as Asp567Asn, Thr449Ala, Iso554Thr, Thr449Ile, Asp567Gly, Ser128Tyr, Ala307Thr, Arg634His, and Thr449Asn. Type II corresponds to cases secondary to high HCG levels, such as hydatidiform mole and multiple pregnancies. Type III is related to hypothyroidism with high TSH levels, and levothyroxine could relieve the symptoms to some extent[3]. Type IV is related to gonadotrophin adenomas secreting FSH or LH. In recent years, studies have found that FSHR gene mutations can be activated not only by FSH, but also by the glycoprotein hormones having the same β subunit[14] such as TSH, LH, and HCG, increasing its sensitivity to HCG produced during natural pregnancy and leading to the occurrence of OHSS during natural pregnancy, and this kind of sOHSS has familial disposition and recurrent characteristics[15]. Alternative theories might include the presence of variant HCG or variant TSH that exhibits higher biological activity or granulosa cells in an autocrine environment that is more sensitive to FSHR stimulation.

Our first patient presented a singleton natural pregnancy with high HCG values but normal levels of TSH. The second patient showed a twin pregnancy with a history of OHSS and normal TSH values, which fulfills the criteria of type II OHSS. However, we did not detect whether there was a mutation in FSHR, so it was uncertain whether our cases belonged to type I.

Unlike the iatrogenic OHSS, sOHSS usually occurs between 8-14 wk of pregnancy[15]. During the pregnancy, HCG usually peaks between the 8th and 10th gestational week and declines thereafter. The second case is uncommon with regard to three aspects: (1) OHSS occurred in a pregnancy following a thawed embryo transfer cycle; (2) Onset of OHSS was not earlier than 17 wk of gestation; and (3) The syndrome continued until delivery with caesarean section. This case highlights the fact that females with a history of OHSS may have a higher risk for sOHSS and should be closely monitored. A twin pregnancy characterized by elevated HCG levels might be one reason for sOHSS. Single embryo transfer may decrease the risk of the development of severe OHSS in cases in which freezing of all embryos is used to prevent OHSS.

OHSS is a self-limiting disease and could be predicted by high-risk factors during ovulation induction. Effective prevention measures can reduce the risk of moderate to severe iatrogenic OHSS. However, sOHSS cannot be predicted. Therefore, early diagnosis and early management of sOHSS are particularly important. In the diagnostic procedure, the first-line investigation for the diagnosis is pelvic ultrasonography. It is a cost-efficient and non-invasive examination which can reflect the states of the fetus, ovaries, and ascites. Based on the comprehensive understanding of sOHSS, we should also give an eye on ovarian malignant tumors to avoid misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis. The ovaries of woman with sOHSS are mostly bilateral polycystic and the capsule wall is thin. In comparison, an ovarian malignant tumor is characterized by a unilateral solid-cystic cyst with a thick capsule wall. Because CA125 increases during the first trimester, it is not accurate for the diagnosis of ovarian tumor during pregnancy. Currently, conservative treatment is the primary management option, and surgery is only needed for cases of ovarian rupture, ovarian torsion, intra-abdominal hemorrhage, or ectopic pregnancy[13]. Pregnancy with sOHSS is a rare disease, and is not easy to detect in the early phase, so obstetricians and gynaecologists should have a comprehensive understanding of sOHSS to make correct diagnosis and treatment, avoiding premature termination of pregnancy and unnecessary surgery damaging the fertility of the patients.

sOHSS is extremely rare. It is always confused with ovarian tumors with abdominal distension, ascites, and enlarged ovaries. The first line investigation for the diagnosis is pelvic ultrasonography. Since sOHSS cannot be predicted, patients with a history of OHSS should be closely monitored. Conservative treatment is the primary option of management. Single embryo transfer may decrease the risk of developing severe OHSS in assisted reproductive cases.

We are grateful to these two patients for providing the information and support, as well as providing the written informed consent allowing us to publish their data. We thank Rui-Hao Wang (from Department of Neurology, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany) for his assistance in improving the quality of written English.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Larentzakis A S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Pellicer A, Albert C, Mercader A, Bonilla-Musoles F, Remohí J, Simón C. The pathogenesis of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: in vivo studies investigating the role of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and vascular endothelial growth factor. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:482-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zalel Y, Katz Z, Caspi B, Ben-Hur H, Dgani R, Insler V. Spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome concomitant with spontaneous pregnancy in a woman with polycystic ovary disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:122-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Langroudi RM, Amlashi FG, Emami MH. Ovarian cyst regression with levothyroxine in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome associated with hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2013;2013:130006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhou X, Duan Z. A case of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome following a spontaneous complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28:850-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wu X, Zhu J, Zhao A. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in a spontaneous pregnancy with invasive mole. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:817-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Macchia E, Simoncini T, Raffaelli V, Lombardi M, Iannelli A, Martino E. A functioning FSH-secreting pituitary macroadenoma causing an ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome with multiple cysts resected and relapsed after leuprolide in a reproductive-aged woman. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28:56-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Castelo-Branco C, del Pino M, Valladares E. Ovarian hyperstimulation, hyperprolactinaemia and LH gonadotroph adenoma. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19:153-155. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Gil Navarro N, Garcia Grau E, Pina Pérez S, Ribot Luna L. Ovarian torsion and spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in a twin pregnancy: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;34:66-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lipitz S, Grisaru D, Achiron R, Ben-Baruch G, Schiff E, Mashiach S. Spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation mimicking an ovarian tumour. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:720-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Panagiotopoulou N, Byers H, Newman WG, Bhatia K. Spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: case report, pathophysiological classification and diagnostic algorithm. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169:143-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chauhan AR, Prasad M, Chamariya S, Achrekar S, Mahale SD, Mittal K. Novel FSH receptor mutation in a case of spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome with successful pregnancy outcome. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2015;8:230-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hugon-Rodin J, Sonigo C, Gompel A, Dodé C, Grynberg M, Binart N, Beau I. First mutation in the FSHR cytoplasmic tail identified in a non-pregnant woman with spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Topdagi Yilmaz EP, Yapca OE, Topdagi YE, Kaya Topdagi S, Kumtepe Y. Spontaneous Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome with FSH Receptor Gene Mutation: Two Rare Case Reports. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2018;2018:9294650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mittal K, Koticha R, Dey AK, Anandpara K, Agrawal R, Sarvothaman MP, Thakkar H. Radiological illustration of spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Pol J Radiol. 2015;80:217-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Smits G, Olatunbosun O, Delbaere A, Pierson R, Vassart G, Costagliola S. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome due to a mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:760-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |