Published online Sep 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2605

Peer-review started: March 18, 2019

First decision: July 30, 2019

Revised: August 4, 2019

Accepted: August 20, 2019

Article in press: August 20, 2019

Published online: September 6, 2019

Processing time: 173 Days and 22.8 Hours

Organ-associated pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferation (PMP) is a very rare disorder. In the urogenital tract, PMP preferentially involves the urinary bladder; kidney involvement is rare. Here, we report a rare case of PMP with ossification in the lower pole of the kidney, which mimics urothelial carcinoma or an osteogenic tumor.

A Chinese man was admitted to our hospital due to intermittent hematuria for more than 1 mo. Enhanced renal computed tomography revealed a mass in the left renal pelvis and upper ureter. The preoperative clinical diagnosis was renal pelvic carcinoma, determined by imaging examination and biopsy. After a standard preparation for surgery, the patient underwent retroperitoneoscopic radical nephroureterectomy. The operative findings were an extensive renal tumor (6 cm × 4.5 cm × 4.5 cm) invading the lower pole of the kidney and upper ureter. The final pathological diagnosis was organ-associated PMP with ossification. After 6-mo follow-up, no recurrence or metastasis was found.

This case of PMP was unusual for its mimicking renal pelvic carcinoma in imaging examinations, making biopsy necessary.

Core tip: Organ-associated pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferation (PMP) in the urinary bladder has been reported. However, it rarely occurs in the kidney and no previous case of renal PMP with ossification have been reported. In this case report, the preoperative clinical diagnosis of renal pelvic carcinoma was made by imaging examination and biopsy. Retroperitoneoscopic radical nephroureterectomy was performed, and the final pathological diagnosis was organ-associated PMP with ossification. This case may help us to better understand this disease with regards to the related clinical manifestations, laboratory examination, imaging and pathologic results.

- Citation: Zhai TY, Luo BJ, Jia ZK, Zhang ZG, Li X, Li H, Yang JJ. Organ-associated pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferation with ossification in the lower pole of the kidney mimicking renal pelvic carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(17): 2605-2610

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i17/2605.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2605

Organ-associated pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferation (PMP), also known as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, pseudomalignant spindle cell proliferation and inflammatory pseudotumor, was first reported by Roth et al[1] in 1980. In general, the organ-associated PMP is a rare type of benign spindle cell tumor. The most commonly reported diagnoses involve the urinary bladder. Other potential sites where PMPs may occur include the head, neck, abdomen, pelvic cavity, retroperitoneum, and limbs[2]. Cases involving the kidney have been reported rarely, and no previous cases of renal PMP with ossification have been reported[3].

According to the 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the urinary system and male genital organs, PMP is a benign mesenchymal bladder tumor with malignant potential derived from fibroblasts and myofibroblasts[4]. For the rare cases that have been reported in the kidney, either the renal parenchyma or the renal pelvis have been involved; furthermore, in these cases the tumor has presented in single, multiple or bilateral forms. Finally, the proportion of male-to-female patients in China is about 2:1, and the mean age is approximately 30 years old.

Herein, we report a rare case of PMP with ossification in the lower pole of the kidney, which mimicked urothelial carcinoma or an osteogenic tumor.

A 72-year-old man without prior contributory history presented with intermittent gross hematuria that had lasted for more than 1 mo. On the day before the hospital consultation, the symptoms had worsened remarkably and were accompanied by lower abdominal and back pain, which were relieved after urination.

The patient’s past history was unremarkable.

The patient’s family history was unremarkable.

The preoperative physical examination provided findings that were unremarkable.

Routine blood testing showed normal erythrocyte count (4.23 × 1012/L; normal range: 4.3-5.8 × 1012/L) and hemoglobin level (138 g/L; normal range: 130-175 g/L). Routine urine test showed occult blood of 3+, substantially elevated erythrocyte count (2512/μL; normal range: 0-7/μL) and high end of normal leucocyte count (12/μL; normal range: 0-12/μL). Urine culture was positive for Enterococcus faecalis.

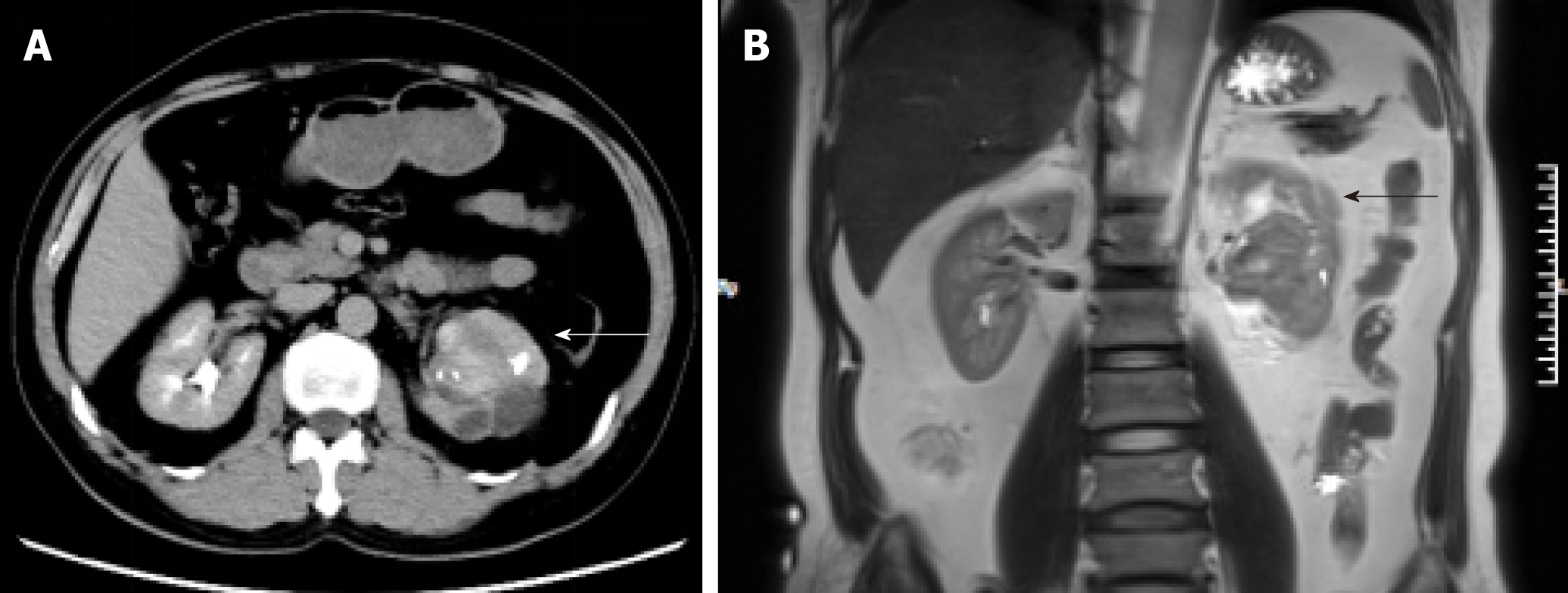

Enhanced renal computed tomography (CT) showed a heterogeneous mass 6 cm in diameter at the left pyeloureteral junction, which indicated a benign lesion or hematoma (Figure 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the left renal pelvis was occupied by a cystic and solid mass (approximately 6.0 cm × 4.5 cm × 4.5 cm in size) with calcification or ossification, which indicated a hamartoma or teratoma (Figure 1B). Emission CT showed that the left renal glomerular filtration rate was 15.4 mL/min and the right renal glomerular filtration rate was 58.9 mL/min (normal range: 80-120 mL/min).

According to the pathological examination, the final diagnosis was renal organ-associated PMP with ossification.

In order to define the pathology of the lesion, a flexible ureteroscopic examination was performed and biopsy taken of the large mass (6 cm in diameter) in the left renal pelvis. Microscopic examination of the biopsy sample showed a highly proliferative area composed of spindle cells and irregular bone tissue. Heterotopic ossification was considered, and osteogenic tumor could not be excluded completely. To address the suspicion of renal pelvic carcinoma, a retroperitoneoscopic radical nephrourete-rectomy was performed.

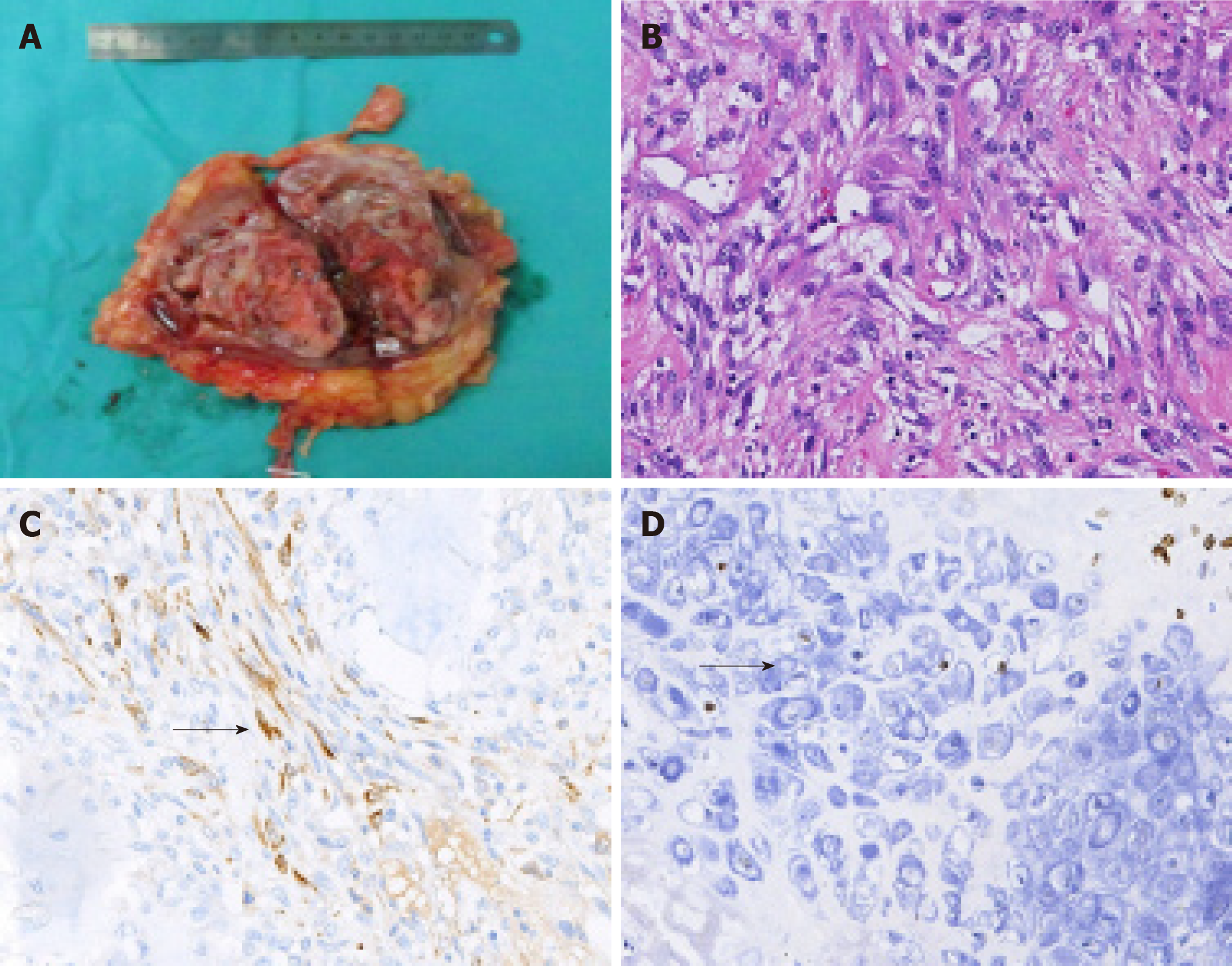

The gross specimen presented as a gray-white and pink-grey mass with capsule, in the lower pole of the kidney (Figure 2A), with a negative surgical margin. Histopathologic features suggested it was an organ-associated PMP with ossification and chondrification of the left kidney (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for calponin, SATB-2, and for Ki-67 (60%) (Figure 2C and 2D), and negativity for CK and P16.

After a 6-mo follow-up, the patient did not complain of obvious discomfort and no signs of recurrence were found.

The pathogenesis of PMP is unknown. In kidney, the tumor itself may represent a reactive hyperplasia related to chronic inflammation of the renal parenchyma. Many microorganisms, such as mycobacterium, corynebacterium, human herpes virus, Epstein-Barr virus and human papillomavirus, have been proposed as potential pathogenic factors[5-7]. In our case, the urine culture was positive for Enterococcus faecalis, supporting the possibility of such an association with chronic inflammation of the renal parenchyma.

Previous studies have indicated an association between PMP and expression of activin receptor-like kinase 1 and p80 expression or chromosomal rearrangements involving 2p23. It remains unknown, however, whether the tumor itself is reactive or neoplastic in nature. While renal clear cell carcinoma, chromophobe cell carcinoma and sarcoma with ossification have all been reported in the literature[8,9], no previous case of renal PMP with ossification has been reported. The mechanism of ossification is thus similarly unclear. We conjecture that it may be related to the transformation of immature fibroblasts into osteoblasts or chondrocytes in the mesenchymal tissue, due to the repair of tissue damage.

The clinical manifestations of renal PMP lack specificity and are mainly comprised of lumbago, fever, hematuria and renal percussion pain. As such, diagnosis of renal PMP depends on imaging and histopathological examination. The tumors appear as a solid mass of low density or slightly high density on CT scans, with contrast-enhanced CT images showing a low degree of enhancement. In MRI, the masses usually show low signal intensity with heterogeneous or homogeneous enhancement on T1- and T2-weighted images[10,11].

In our case, the CT showed a heterogeneous mass and MRI showed a cystic and solid mass with ossification in the left renal pelvis and upper ureter, which made it difficult to distinguish from renal pelvic carcinoma and osteogenic tumors. The differential diagnosis of renal PMP includes renal cell carcinoma, renal sarcoma, teratoma, and renal pelvic carcinoma. However, renal PMPs are characterized by obscure edges, whereas the margins of renal cell carcinoma are clear. The CT-enhanced scans of our patient showed a gradual, slight enhancement in the renal PMP, different from the typical flow-type enhancement of renal cell carcinoma.

It was difficult to establish the diagnosis preoperatively. As such, the final diagnosis was dependent on findings from histopathologic and immunohistochemical examinations of the biopsied tissue. Microscopically, PMP lesions are mainly composed of proliferative fusiform myofibroblasts and inflammatory cells, lacking severe cytologic atypia and containing fewer mitoses than sarcomas[3]. Expression of p53 has been proposed as a marker to differentiate PMPs (usually negative on immunostain) from sarcomas (usually positive)[12]. In our case, the biopsied mass showed negativity for CK5/6, p53 and p16, along with positivity for calponin, smooth muscle actin and other smooth muscle-derived markers.

At present, there is no standard treatment regimen for renal PMP. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are recommended, accompanied by symptomatic treatment and traditional Chinese medicine. If conservative treatment is ineffective, simple tumor resection or partial nephrectomy would be feasible. It was recently reported that Myofibroblastic tumour patients had promising results with crizotinib treatment, so tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can be used as an alternative to conservative treatment[13,14]. For tumors that are difficult to completely resect, TKIs can be also used as neoadjuvant therapy. However, since in most cases the prognosis of renal PMPs is good, TKIs adjuvant therapy after operation is not recommended routinely. According to our experience, It is recommended that CT examination be performed 3-mo or 6-mo in the first two years after operation, if nothing special found in the CT result,the re-examination time may extend to every 6-mo or 1 year afterwards. For patients undergoing partial nephrectomy, CT examination is also recommended 1-mo after operation. Most patients have a satisfactory prognosis, and for our case, the patient did not complain of any obvious discomfort at the 6-mo follow-up and no signs of recurrence were found.

Renal organ-associated PMP is a rare lesion that may mimic renal pelvic carcinoma, clinically and radiologically. Diagnosis of renal PMP depends on imaging and histopathological examination. Conservative treatment is recommended, and a satisfactory prognosis can be achieved.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Exbrayat JM, Mehdi I S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Roth JA. Reactive pseudosarcomatous response in urinary bladder. Urology. 1980;16:635-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:859-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1100] [Cited by in RCA: 1030] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Leroy X, Copin MC, Graziana JP, Wacrenier A, Gosselin B. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the renal pelvis. A report of 2 cases with clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1209-1212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part A: Renal, Penile, and Testicular Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70:93-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1478] [Cited by in RCA: 2071] [Article Influence: 230.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Montgomery EA, Shuster DD, Burkart AL, Esteban JM, Sgrignoli A, Elwood L, Vaughn DJ, Griffin CA, Epstein JI. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the urinary tract: a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases, including a malignant example inflammatory fibrosarcoma and a subset associated with high-grade urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1502-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dobrosz Z, Ryś J, Paleń P, Właszczuk P, Ciepiela M. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the bladder - an unexpected case coexisting with an ovarian teratoma. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Selves J, Meggetto F, Brousset P, Voigt JJ, Pradère B, Grasset D, Icart J, Mariamé B, Knecht H, Delsol G. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. Evidence for follicular dendritic reticulum cell proliferation associated with clonal Epstein-Barr virus. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:747-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hartman RJ, Helfand BT, Dalton DP. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma with osseous metaplasia: a case report. Can J Urol. 2011;18:5564-5567. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kaneko T, Suzuki Y, Takata R, Takata K, Sakuma T, Fujioka T. Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the kidney. Int J Urol. 2006;13:285-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park SB, Cho KS, Kim JK, Lee JH, Jeong AK, Kwon WJ, Kim HH. Inflammatory pseudotumor (myoblastic tumor) of the genitourinary tract. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1255-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Patnana M, Sevrukov AB, Elsayes KM, Viswanathan C, Lubner M, Menias CO. Inflammatory pseudotumor: the great mimicker. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:W217-W227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ledet SC, Brown RW, Cagle PT. p53 immunostaining in the differentiation of inflammatory pseudotumor from sarcoma involving the lung. Mod Pathol. 1995;8:282-286. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Felkai L, Bánusz R, Kovalszky I, Sápi Z, Garami M, Papp G, Karászi K, Varga E, Csóka M. The Presence of ALK Alterations and Clinical Relevance of Crizotinib Treatment in Pediatric Solid Tumors. Pathol Oncol Res. 2019;25:217-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kiratli H, Uzun S, Varan A, Akyüz C, Orhan D. Management of anaplastic lymphoma kinase positive orbito-conjunctival inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with crizotinib. J AAPOS. 2016;20:260-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |