Published online Sep 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2573

Peer-review started: March 15, 2019

First decision: July 30, 2019

Revised: August 1, 2019

Accepted: August 20, 2019

Article in press: August 20, 2019

Published online: September 6, 2019

Processing time: 176 Days and 7 Hours

The portosystemic shunt is the pathway between the portal vein (PV) and systemic circulation. A spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (SPISS) is a rare portosystemic shunt type. Here we report an extremely rare type of SPISS, a spontaneous intrahepatic PV-inferior vena cava shunt (SPIVCS).

A 66-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with the complaint of abdominal distention and a decreased appetite for 1 mo. The patient had a 20-year history of hepatitis B surface antigen positivity and a 5-year history of cirrhosis. She had been treated with Chinese herbal medicine for a long time. Liver function tests showed: alanine aminotransferase, 35 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 42 U/L; serum albumin (ALB) 32.2 g/L; and serum ascites ALB gradient, 25.2 g/L. Abdominal ultrasonography and enhanced computed tomography showed that the left branch of the PV was thin and occluded; the right branch of the PV was thick and showed a vermicular dilatation vein cluster in the upper pole of the right kidney that branched out and converged into the inferior vena cava from the bare area of the lower right posterior lobe of the liver. We diagnosed her with an extremely rare SPIVCS caused by portal hypertension and provided symptomatic treatment after admission. One week later, her symptoms disappeared and she was discharged.

SPIVCS is a rare portosystemic shunt with a clear history of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Clarifying the type PV shunt has important clinical significance.

Core tip: Here we report a spontaneous intrahepatic portal vein (PV)-inferior vena cava shunt. A 66-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a 20-year history of HBsAg and a 5-year history of cirrhosis. Abdominal ultrasonography and enhanced computed tomography showed that the left branch of the PV was thin and occluded; the right branch of the PV was thick and showed a vermicular dilatation vein cluster in the upper pole of the right kidney that branched out and converged into the inferior vena cava from the bare area of the lower right posterior lobe of the liver.

- Citation: Tan YW, Sheng JH, Tan HY, Sun L, Yin YM. Rare spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in hepatitis B-induced cirrhosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(17): 2573-2579

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i17/2573.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2573

Liver cirrhosis is often accompanied by portal hypertension, which often manifests as esophageal varices, ascites, splenomegaly, hypersplenism, upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, portosystemic shunt encephalopathy, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis[1]. Spontaneous portosystemic shunt (SPSS), a common but insufficient clinical manifestation, is a result of compensation of portal hypertension in cirrhosis[2]. The shunt can be congenital or acquired[3]. The incidence rate of SPSS in patients with cirrhosis is 38%-40%, and the incidence rate of splenorenal shunt (SRS) is 14%-21%[4]. The most common types of SPSS are SRS and umbilical vein recanalization[5]. Rare types include collateral veins in gastric varices, gallbladder varices, thrombotic portal vein (PV), intestinal-caval shunt, and right portal–renal vein shunt[6]. Spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (SPISS), a rare SPSS type, includes PV branches that directly shunt to the intrahepatic vein and PV branches that shunt to the extrahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC).

We recently encountered a 66-year-old woman with a 20-year history of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity. We found that she had an extremely rare SPISS, a spontaneous intrahepatic PV-IVC shunt (SPIVCS) caused by portal hypertension.

A 66-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with the complaint of a 1-mo history of abdominal distention and decreased appetite.

She had no history of ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, or hepatic encephalopathy. She had no history of alcohol abuse or hepatitis C.

The patient also had a 20-year history of HBsAg positivity and had been treated with Chinese herbal medicine for a long time. In the past 5 years, she had been diagnosed with cirrhosis induced by hepatitis B by a rural doctor.

No alcohol abuse and no other drug and herbal used. No additional family history. While her daughter had history of HBsAg positivity but no history of hereditary diseases.

A physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 135/82 mmHg, heart rate of 78 beats/min, temperature of 36.8°C, and breathing rate of 18 times/min. Her skin was dark and gloomy; no yellowing of the skin and mucosa was evident; visible liver palms and spider angioma, an abdominal bulge, and visible abdominal wall vein exposure were evident, and splenomegaly (4 cm below the left midclavicular line–left ribs junction) were evident; no abdominal pain was reported; and the ascites buckle sign was positive.

Routine bloodwork revealed the following: red blood cell count, 2.13 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 6.12 g/L; white blood cell count, 2.43 × 109/L; neutrophil count, 1.86 × 109/L; and platelet count, 5.25 × 1012/L. Liver function test results were as follows: alanine aminotransferase, 35 U/L (10-40 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 42 U/L (10-40 U/L); serum total bilirubin, 17.2 µmol/L (1.71-17.1 µmol/L); direct bilirubin, 4.26 µmol/L (0-6.8 µmol/L); serum albumin (ALB), 32.2 g/L (35-53 g/L); serum globulin 28 g/L (20-40 g/L); alkaline phosphatase, 89 U/L (40-120 U/L); glutamide transphthalase, 63 U/L (10-40 U/L); and serum ammonia, 45 µmol/L (27-82 µmol/L). Hepatitis B virus (HBV) markers were as follows: HBsAg, 26 IU/mL (< 0.05 IU/mL); anti-HBs, 0.001 mIU/mL (< 10 mIU/mL); anti-hepatitis B e antigen, 2.143 Paul Ehrlich international units (PEIU)/mL (< 0.2 PEIU/mL); anti-hepatitis B core antigen, 3.221 PEIU/mL (< 0.9 PEIU/mL).

Other results were as follows: HBV DNA, not detected (< 20 IU/mL); alpha fetoprotein, 4.25 µg/L (< 20 ng/mL); ascites examination, clear; Li Fanta test, negative; nucleated cell count, 0.82 × 109/L; monocyte ratio, 55%; polymorphonuclear cell ratio, 45%; and serum ascites ALB gradient, 25.2 g/L.

Antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-liver/kidney microsome antibody type 1, anti-nuclear glycoprotein antibody, anti-soluble acid nucleoprotein antibody, soluble acidic nucleoprotein antibody, anti-hepatocyte cytoplasmic antigen type 1 antibody, anti-soluble liver antigen/hepatopancreatic antigen antibody, and other tests were negative. Other levels were: immunoglobulin G (IgG), 13.1 g/L (7.11-16 g/L); IgG4, 0.08 g/L (≤ 2.01 g/L); and ceruloplasmin, 0.33 g/L (0.2-0.6 g/L).

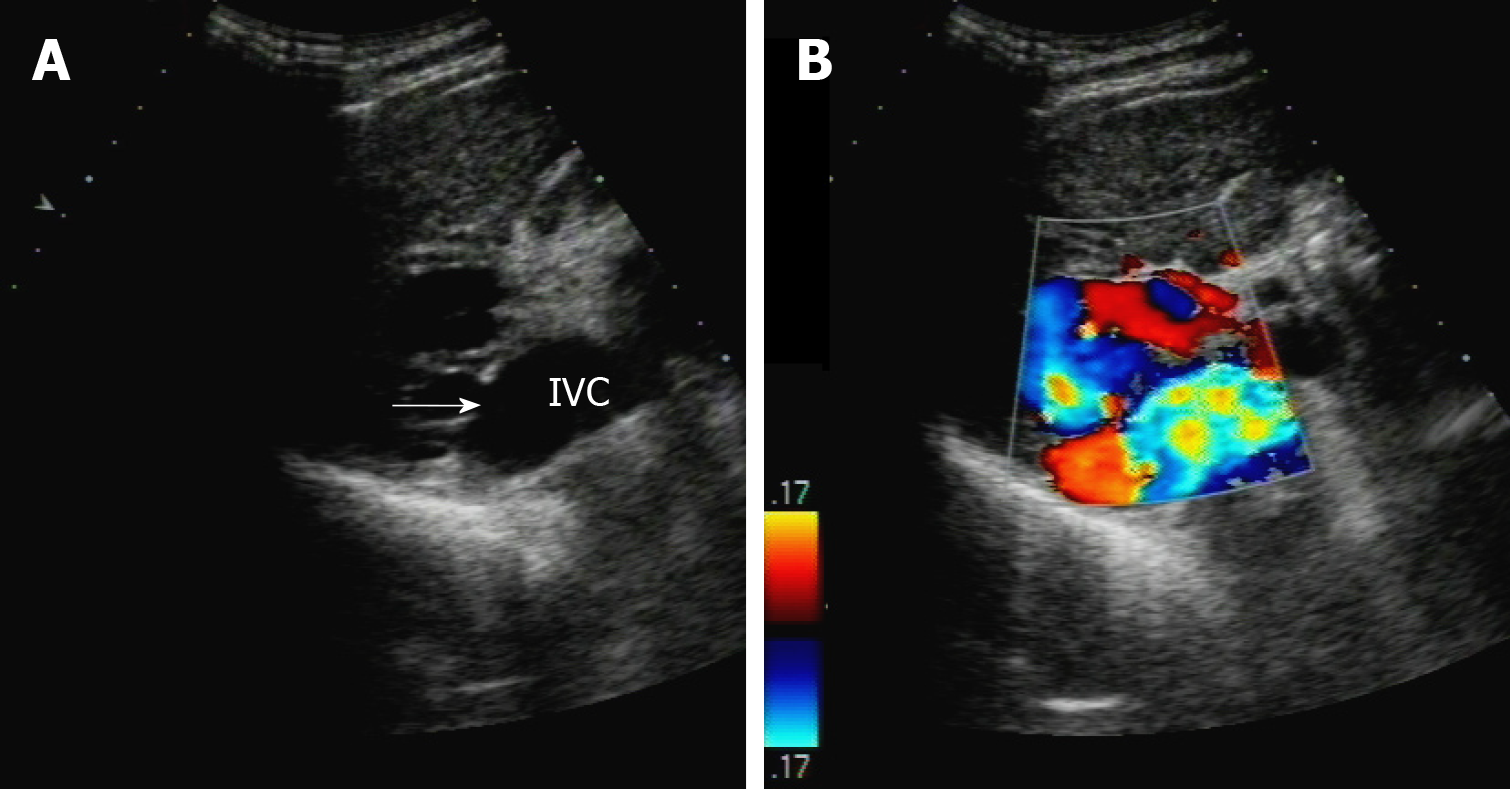

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed that echoes of the liver showed dense thickening and an uneven intrahepatic structure disorder; the liver capsule was unclear and irregular. The right branch of the PV showed obvious dilatation (local dilatation, up to 48 mm), was connected with the IVC, and showed a turbulent local spectrum, as shown in Figure 1.

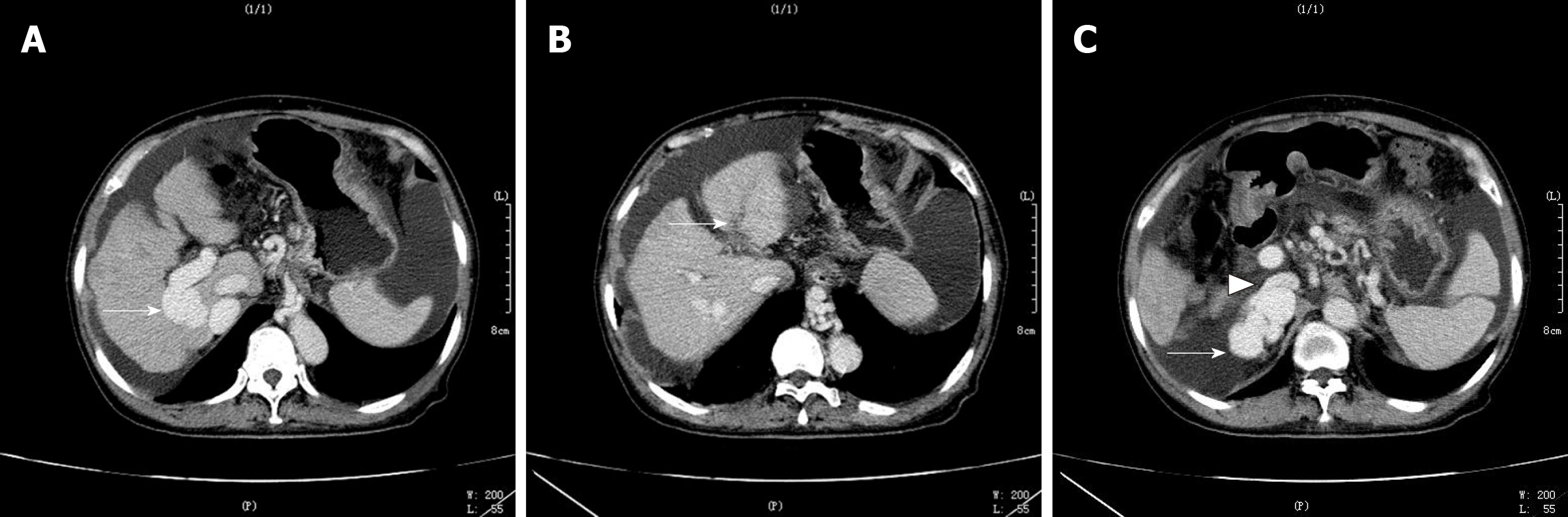

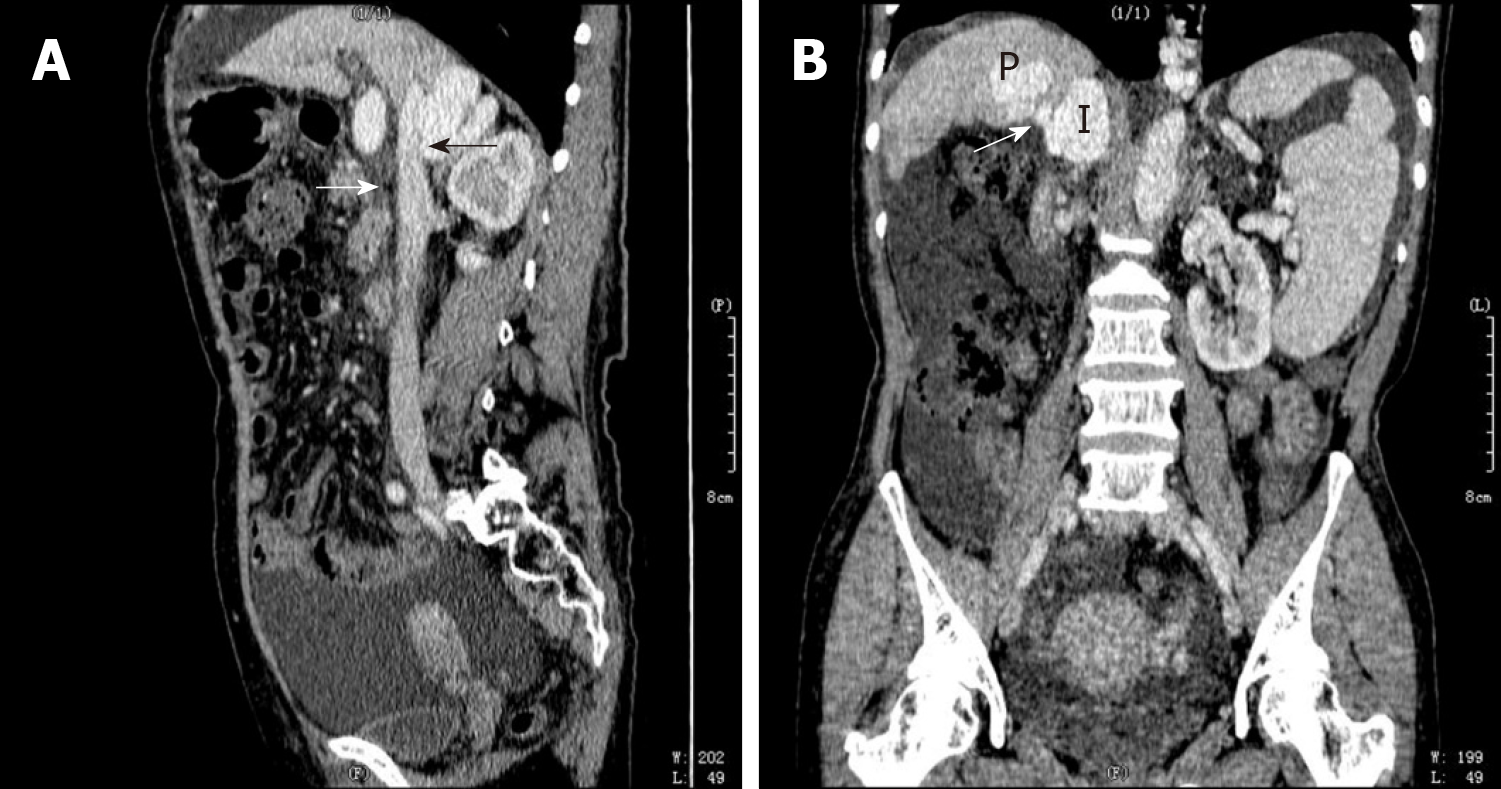

Abdomen enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed that the left branch of the PV was thin and occluded, while the right branch of the PV was thick, showed a vermicular dilatation vein cluster, branched out, and converged into the IVC from the bare area of the lower right posterior lobe of the liver, forming a venous dilatation vein cluster in the upper pole of the right kidney (Figure 2 and 3). In addition, a vermicular dilatation vein shadow was seen in the inner wall of the lower esophagus, perineural space, and hepatic-gastric space and the splenic vein diameter was increased to 1.7 cm. A portion of the liver lobe was disordered and the hepatic fissure was widened. The spleen was enlarged and numerous liquid shadows were visible in the abdominal cavity.

A rare SPISS in hepatitis B-induced cirrhosis.

After admission, 3000 mL of ascites fluid was drained, 20 g of human ALB was intravenously infused, and 100 mg of spironolactone and 40 mg of furosemide were administered per day. One week later, the abdominal distension was relieved, her appetite improved, and she was discharged with maintenance therapy of propranolol 20 mg/d.

Follow-up of liver function and ultrasonography every 3 mo after discharge showed no further deterioration of liver function and ascites.

The portosystemic shunt is the pathway between the PV and the systemic circulation[7]. By etiology, it can be divided into congenital and spontaneous types[8] as well as intrahepatic and extrahepatic types according to anatomical location[9].

SPISS is a spontaneous venous pathway that extends from the intrahepatic venous system to the circular venous system[10]. It is mostly acquired, but a congenital type has not been identified[11]. Lalonde et al[12] reported a SPIVCS case which may be belong to the congenital type because the patient was only a 15-year-old adolescent with no evidence of liver cirrhosis or portal hypertension. There are still two types of SPISS: one in which the intrahepatic PV branch shunts to the intrahepatic vein, and another in which the intrahepatic PV shunts to the IVC through the lateral hepatic branch. The first type can occur in cases of tumors, liver trauma, or Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS)[13,14]. The second type is very rarely discussed and refers to the right posterior branch of the PV connected with the IVC through the right posterior lobe of the liver in the right adrenal region. SPIVCS is common in cirrhosis patients with portal hypertension. Its possible anatomical basis is that the right branch of the PV communicates with the IVC through the accessory hepatic vein or the subcapsular venous plexus of the liver. Since there is no standard proper term to describe this type of shunt, we refer to it as SPIVCS.

Abernethy malformation is also a SPSS that requires differentiation from SPISS, a rare congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunt malformation caused by abnormal development of the PV system[15]. Morgan and Supefina classified Abernethy malformations as follows[16]: type I, complete portosystemic shunt without PV perfusion in the liver; and type II, partial portosystemic shunt with partial portosystemic blood perfusion in the liver. Type I primarily affects children and women and is often accompanied by other congenital malformations such as biliary atresia, polysplenoma, heart defects, and liver tumors. Type II is rarer, primarily affects men, and features few other congenital malformations. Moreover, Abernethy malformation has no underlying diseases such as cirrhosis or portal hypertension and primarily affects children[17].

We retrieved the PubMed database using “intrahepatic portosystemic shunt,” “intrahepatic portal cavity shunt,” “spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic shunt,” and “portoinferior vena cava shunt” keywords and MeSH terms, respectively. By January 31, 2019, six articles describing intrahepatic SPSS similar to ours were found, as shown in Table 1.

| Report-ers | Country | Sex | Old (yr) | History of liver disease | Encephalopathy | Serum ammonia | Liver function test | Splenomegaly | The maximum diameters of shunt | |||

| Kwon et al[10] | Korea | Woman | 42 | No | Yes | 146 μg/dL | ALT, 152 U/L; AST, 112 U/L; | No | 30.4 mm | |||

| Qi et al[20] | China | Man | 58 | Cirrhosis (HBV) | No | 35 μmol/L | TBIL, 48.9 μmol/L, ALT, 66.04 U/L, AST, 93.11 U/L | Moderate | ND | |||

| Tsauo et al[21] | China | Woman | 36 | Cirrhosis (AIH) | ND | ND | ND | Yes | ND | |||

| Vennarecci et al[18] | Italy | ND | ND | ND | Yes | ND | ND | Yes | ND | |||

| Lalonde et al[12] | Belgium | Man | 15 | No | No | ND | Abnormal liver function | No | 20 mm | |||

| Peng-Xu Ding et al[14] | China | Woman | 42 | Cirrhosis (HCV) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||

During liver transplantation for severe hepatic encephalopathy, Vennarecci[18] found a very thick shunt between the right branch of the PV and IVC, which made the operation more difficult. The shunt vein was torn during the operation, causing a massive hemorrhage. After hemostasis was achieved, the surgical strategy was changed to hepatectomy from the left side to the right side. Therefore, the SPIVCS shunt will increase the liver transplantation difficulty. Another SPISS type, which involves the PV branches directly shunting to the intrahepatic vein, can be caused by intrahepatic tumors and trauma or occur spontaneously[19].

BCS characterized by obstructive lesions of the hepatic vein and the IVC is another cause of SPISS that is shunted to the vena cava system via the subcapsular or intrahepatic veins[14]. The use of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is an effective treatment for BCS-induced SPISS.

Kwon et al[10] reported a case of laparoscopic surgery used to circumcise the inflow of varicose veins. Their patient’s hepatic encephalopathy improved postoperatively and liver function returned to normal. No shunt reappeared on a CT scan 8 mo later.

SPIVCS is a rare portosystemic shunt with a clear history of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Clarifying the PV shunt has important clinical significance: (1) it aids the differential diagnosis of PV aneurysm and right adrenal lesion; (2) it guides clinical treatment because patients with PV shunt are more likely to suffer from hepatic encephalopathy induced by elevated blood ammonia; and (3) for patients who need surgical or other interventions such as abdominal puncture, the shunt helps the surgeon plan ahead of time.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Poddighe D, Dumitrascu DL S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Simpson JA, Conn HO. Role of ascites in gastroesophageal reflux with comments on the pathogenesis of bleeding esophageal varices. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:17-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lipinski M, Saborowski M, Heidrich B, Attia D, Kasten P, Manns MP, Gebel M, Potthoff A. Clinical characteristics of patients with liver cirrhosis and spontaneous portosystemic shunts detected by ultrasound in a tertiary care and transplantation centre. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1107-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pocha C, Maliakkal B. Spontaneous intrahepatic portal-systemic venous shunt in the adult: case report and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1201-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li M, Li Q, Lei Q, Hu J, Wang F, Chen H, Zhen Z. Unusual bleeding from hepaticojejunostomy controlled by side-to-side splenorenal shunt: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zardi EM, Uwechie V, Caccavo D, Pellegrino NM, Cacciapaglia F, Di Matteo F, Dobrina A, Laghi V, Afeltra A. Portosystemic shunts in a large cohort of patients with liver cirrhosis: detection rate and clinical relevance. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:76-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | von Herbay A, Frieling T, Häussinger D. Color Doppler sonographic evaluation of spontaneous portosystemic shunts and inversion of portal venous flow in patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2000;28:332-339. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Pillai AK, Andring B, Patel A, Trimmer C, Kalva SP. Portal hypertension: a review of portosystemic collateral pathways and endovascular interventions. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:1047-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Henseler KP, Pozniak MA, Lee FT, Winter TC. Three-dimensional CT angiography of spontaneous portosystemic shunts. Radiographics. 2001;21:691-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kamel IR, Lawler LP, Corl FM, Fishman EK. Patterns of collateral pathways in extrahepatic portal hypertension as demonstrated by multidetector row computed tomography and advanced image processing. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:469-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kwon JN, Jeon YS, Cho SG, Lee KY, Hong KC. Spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic shunt managed by laparoscopic hepatic vein closure. J Minim Access Surg. 2014;10:207-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Golli M, Kriaa S, Said M, Belguith M, Zbidi M, Saad J, Nouri A, Ganouni A. Intrahepatic spontaneous portosystemic venous shunt: value of color and power Doppler sonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2000;28:47-50. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Lalonde L, Van Beers B, Trigaux JP, Delos M, Melange M, Pringot J. Focal nodular hyperplasia in association with spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt. Gastrointest Radiol. 1992;17:154-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Borentain P, Soussan J, Resseguier N, Botta-Fridlund D, Dufour JC, Gérolami R, Vidal V. The presence of spontaneous portosystemic shunts increases the risk of complications after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97:643-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ding PX, Li Z, Han XW, Zhang WG, Zhou PL, Wang ZG. Spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:742.e1-742.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lemoine C, Nilsen A, Brandt K, Mohammad S, Melin-Aldana H, Superina R. Liver histopathology in patients with hepatic masses and the Abernethy malformation. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:266-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Morgan G, Superina R. Congenital absence of the portal vein: two cases and a proposed classification system for portasystemic vascular anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1239-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Soota K, Klair JS, LaBrecque D. Confusion for Fifteen Years: A Case of Abernethy Malformation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:A50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vennarecci G, Levi Sandri GB, Laurenzi A, Ettorre GM. Spontaneous intrahepatic portocaval shunt in a patient undergoing liver transplantation. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Soon MS, Chen YY, Yen HH. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Qi X, Ye C, Hou Y, Guo X. A large spontaneous intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in a cirrhotic patient. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2016;5:58-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tsauo J, Shin JH, Han K, Yoon HK, Ko GY, Ko HK, Gwon DI. Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt for the Treatment of Chylothorax and Chylous Ascites in Cirrhosis: A Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27:112-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |