Published online Aug 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2406

Peer-review started: March 26, 2019

First decision: May 31, 2019

Revised: July 9, 2019

Accepted: July 20, 2019

Article in press: July 20, 2019

Published online: August 26, 2019

Processing time: 155 Days and 10.9 Hours

Syphilis is a common sexually transmitted disease caused by the Treponema pallidum (T. pallidum). Malignant syphilis is a rare presentation of secondary syphilis. Here, we present a case diagnosed with malignant syphilis accompanied with neurosyphilis.

A 56-year-old man present with a 2-mo history of spreading ulcerous and necrotic papules and nodules covered with thick crusts over the face, trunk, extremities, and genitalia. The patient was diagnosed with malignant syphilis accompanied by neurosyphilis based on the characteristic morphology of the lesions, positive serological and cerebrospinal fluid tests for syphilis, brain magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathology, along with resolution of the lesions following the institution of penicillin therapy. The lesions and neurological condition successfully resolved after a course of treatment with penicillin.

We suggest that neurosyphilis should be considered whenever people have psychiatric symptoms without cutaneous lesions or human immunodeficiency virus.

Core tip: We present a 53-year-old malnourished man with a two-month history of spreading ulcerative and necrotic cutaneous lesions with psychiatric symptoms. The patient was diagnosed with malignant syphilis accompanied by neurosyphilis based on the characteristic morphology, positive serological and cerebrospinal fluid tests, and histopathology, with resolution of the lesions following penicillin therapy. We report the case to emphasize the diagnosis of the disease, and its association not only with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), but also with other poor health conditions, specifically malnutrition. We suggest that neurosyphilis should be considered whenever people have psychiatric symptoms even in case of no cutaneous lesions or HIV infection.

- Citation: Ge G, Li DM, Qiu Y, Fu HJ, Zhang XY, Shi DM. Malignant syphilis accompanied with neurosyphilis in a malnourished patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(16): 2406-2412

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i16/2406.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2406

Syphilis is a common sexually transmitted disease caused by Treponema pallidum (T. pallidum). The course of the disease normally comprises primary, secondary, latent, tertiary, and neurosyphilis stages. Malignant syphilis, also known as Lues malign or ulceronodular syphilis, an uncommon ulcerative variety of secondary syphilis, is an explosive form of syphilis that was first described in the 19th century. This rare form of syphilis is characterized by a prodrome of fever, headache, and muscle pain followed by a papulopustular eruption that soon becomes necrotic, resulting in sharply demarcated ulcers with a thick, rupioid crust[1,2]. Malignant syphilis most commonly affects individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection[3-5]. However, malignant syphilis has also been noted and described in immunocompetent patients[6-8] and is then commonly associated with alcoholism, malnutrition, hepatitis, pregnancy, and diabetes[9]. When untreated, syphilis can spread to the brain and nervous system (neurosyphilis) during any of the stages described above. Patients co-infected with T. pallidum and HIV are at significantly higher risk for developing neurosyphilis[3,5-6].

Because its range of manifestations is so vast, syphilis has earned the nickname “The Great Imitator”[10], making its diagnosis in the emergency room notoriously difficult. The clinical manifestations of malignant syphilis are different from classical secondary syphilis in that the former is characterized by pleomorphic pustules, nodules, and deep ulcers with thick crusts. This diagnosis is often forgotten or misdiagnosed, especially when an immunocompetent patient presents with spread skin lesions and cerebral manifestations[11]. Here, we present a case diagnosed as malignant syphilis accompanied with neurosyphilis, but first misdiagnosed as psoriasis/pyoderma gangrenosum and cerebral fracture. On the basis of clinical examination, serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) T. pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA), rapid plasma regain (RPR), histological examination, and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the patient was re-diagnosed to be suffering from malignant syphilis and neurosyphilis. The patient recovered following a course of treatment with penicillin.

A 56-year-old male present with a 2-mo history of spreading ulcerous and necrotic papules and nodules covered with thick crusts over the face, trunk, extremities, and genitalia on March 20, 2018 (day 0). The skin lesions initially appeared as small erythematous papules over his back and gradually spread to the chest, face, extremities, and genitals. The lesions progressed to ulcerous/necrotic lesions covered with thick yellowish and blackish crusts. There was no association with systemic manifestations such as fever, weight loss, or headache; however, the patient also suffered from a loss of coordination of movement, personality changes, and changes in speech. The patient was initially diagnosed with pyoderma gangrenosum and treated for 7 d (days -8 to 1) at a local hospital, but his loss of coordination and speech impairment worsened. The patient reported having unprotected sexual activity within the past 2 mo but denied ever having had sex with men. The patient had no other apparent underlying disease. Other possibly relevant habits included smoking 20-40 cigarettes each day for more than 30 years, but the patient denied ever drinking alcohol.

His height and body mass index (BMI) of 18.36 kg/m² together indicated mild malnutrition. Examination revealed pleomorphic ulcers of varying sizes ranging from 1 to 6 cm, circular and oval in shape with sharp borders, covered by yellowish and blackish thick crusts. The lesions were distributed over the face, front and back of the trunk, extremities, and genitals (Figure 1). Neurological examination showed mental confusion, mania, paranoia, and mild motor dysphasia.

Full blood cell count, CD4+ cell count, CD8+ cell count, HIV serotest, hepatitis B and hepatitis C, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and anti-nuclear antibodies, and cultures for fungi and bacteria (including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae) were all normal or negative. Other laboratory analyses showed slightly attenuated albumin (31.3 g/L), anemia (hemoglobin 117 g/L), and elevated C reactive protein (35.00 mg/L), with no other abnormalities. Serum TPPA was positive and RPR test was at a titer of 1:16 (at +1 d).

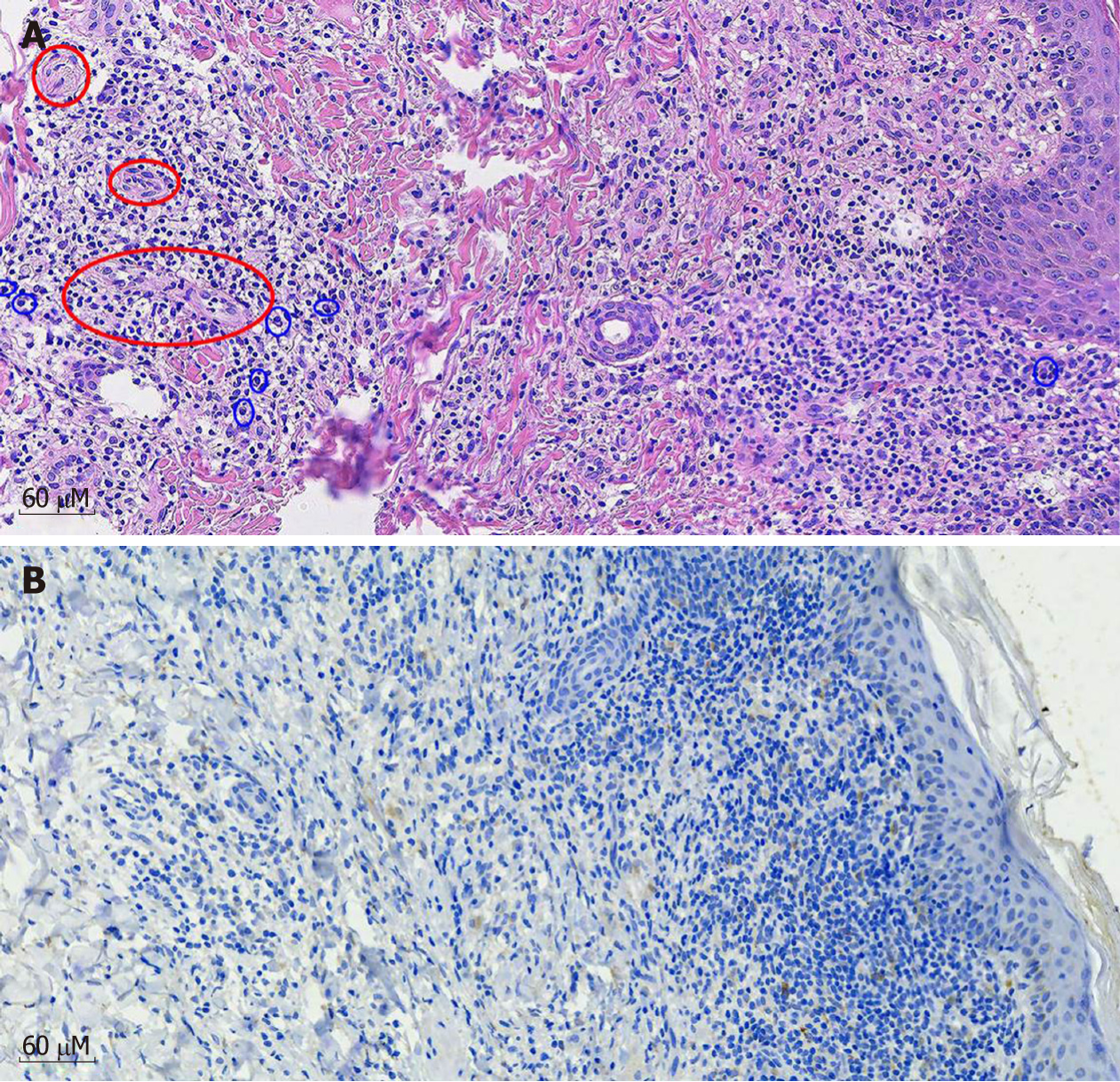

MRI revealed abnormal hyperintense lesions in the bilateral insular cortex and radial crown, and lateral anterior horn (at +1 d) (Figure 2). Histological examination of a biopsy sample from an ulcer on his abdomen indicated obliterative vasculitis as well as infiltration of cells (predominantly lymphocytes and plasma cells) in the dermis (Figure 3A). Staining for fungi, mycobacteria, and spirochetes was all negative. Immunohistochemical staining with a polyclonal antibody against T. pallidum was positive (Figure 3B).

Because the patient was suspected to have neurosyphilis, he was arranged to undergo a lumbar puncture, but at first he refused. After treatment with penicillin (at +11 d), the patient received a lumbar puncture, which showed elevated protein (5.9 mg/dL) and high white blood cell count (16 cells/µL; predominantly lymphocytes) in CSF. TPPA was positive and RPR was negative.

Based on the clinical findings, along with serum TPPA, RPR, histological examination, and MRI, the patient was diagnosed with malignant syphilis with neurosyphilis.

The patient was initially treated with 60 million units of penicillin three times daily for 10 d (from +1 d to +11 d). He did not present with Jarisch-Herxhiemer reaction (JHR) possibly due to the corticosteroids prescribed earlier. The lesions regressed remarkably and quickly and he was discharged from the hospital. The patient continued to respond positively to treatment with 240 million units of penicillin intramuscularly once a week for three weeks, with a complete remission of lesions and neurotic systems.

In next follow-up, the ulcers had healed completely, although atrophic scars remained (Figure 4); the RPR titer dropped to 1:2 and HIV serotest remained negative.

Malignant syphilis is a rare presentation of secondary syphilis, originally described by Bazin in 1859 as a nodular variant of syphilis. With the increase in the incidence of HIV infection, the morbidity as well as the frequency of this disease has increased[12]. It usually occurs from 6 weeks to 1 year after the primary symptoms manifest, or even earlier in people with HIV infection[13,14]. A few cases of malignant syphilis have been described, mostly associated with HIV infection, and it is rarely seen otherwise in patients with poor health conditions, diabetes, or malnutrition[9].

The occurrence of malignant syphilis together with neurosyphilis and malnutrition, as shown in the present case, is extremely rare. A few cases of malignant syphilis have been reported in the literature, most of which had no neurosyphilis or HIV infection[3,15]. In the present case, the patient was not HIV positive, and therefore one of the main risk factors for the development of both malignant syphilis and neurosyphilis was absent.

Typical lesions of malignant syphilis are initially papules that rapidly evolve into pustules and finally form ulcers with an elevated border and necrotic center[16]. The skin lesion mainly affects the trunk and extremities, although the face, scalp, mucous membranes, palms, soles, and genitals can also be involved. Because of the varied clinical manifestations and mimicking of several more common dermatoses, malignant syphilis is almost always misdiagnosed as another disease. In our case, at first the patient was misdiagnosed with pyoderma gangrenosum. When there is clinical suspicion of malignant syphilis, confirmation of the diagnosis will be supported by three criteria: Clinical and histopathological characteristics; presence of high-titer antibodies from Venereal Diseases Research Laboratory (VDRL) or a similar test; and intense and severe JHR and rapid resolution of lesions with adequate therapy. The diagnosis is typically established by strongly positive serological tests, a severe JHR, and an excellent response to antibiotic therapy[17]. In our case, the patient was prescribed with glucocorticoids prior to antibiotic therapy, in which case JHR might have been inhibited. Based on the circumstances of the present case, we believe that severe JHR should not be included as one of the mandatory criteria.

Syphilis can spread to the brain and nervous system (neurosyphilis) during any stage of the course of the disease. Neurosyphilis should be considered for any patients with syphilis accompanied by tabes dorsalis, general paresis, meningovascular neurosyphilis, or other unexplained neurological conditions. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial due to potential persistent disabilities that can be easily treated or prevented if detected early. Brain MRI and CSF analyses are essential for treatment planning and management. In patients with a known syphilis infection who present with neurologic, ophthalmic, or tertiary syphilis symptoms, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a lumbar puncture with a CSF examination[18]. The possibility of neurosyphilis should be promptly investigated, followed by empiric treatment. In the present case, widespread lesions, tabes dorsalis, serum RPR test along with MRI all suggest neurosyphilis, even without brain fluid TPPA and RPR. In addition, CSF showed elevated protein and high white blood cell count with lymphocyte predominance. Also, CSF TPPA was positive and RPR was negative. We considered that RPR was negative due to the initial treatment with penicillin. After these considerations, the patient was diagnosed with malignant syphilis with neurosyphilis.

Pathological studies show that obliterative medium-sized vessel vasculitis and plasma cell infiltrates in the dermis can be valuable tools in a challenging diagnosis[19]. In the classical definition of malignant syphilis, the absence of spirochetes in tissue samples was cited as one diagnostic criterion. However, treponema can occasionally be identified by silver staining such as Steiner or Whartin-Starry techniques. Immunohistochemical staining using monoclonal antibodies against T. pallidum is sometimes helpful to identify microorganisms, especially in secondary syphilis, and has demonstrated a high sensitivity and specificity[2]. In the present case, treponema was not identified using silver staining, however, in agreement with other reports, spirochetes were detected using antibodies against T. pallidum. Therefore, we propose that immunohistochemical staining can be a useful tool for confirming the diagnosis along with the clinical and serologic findings.

Although penicillin is the treatment of choice, there is no special recommended treatment for malignant syphilis. Some authors recommend increasing the dose in cases of poor general health conditions. For resistant cases or relapses, prolonged therapy with high doses of penicillin is suggested[20]. In the present case, the patient was diagnosed with malignant syphilis accompanied with neurosyphilis, and he was initially treated with 60 million units of penicillin daily for 10 d, in view of the fact that crystalline penicillin was able to cross the blood-brain barrier. After he was discharged from the hospital, we chose a total dose of penicillin G benzathine (7.2 million units) for next three weeks. The lesions and neurological condition successfully resolved after the treatment, along with a fourfold decline in serum RPR.

The titers of VDRL or RPR were high in most published malignant syphilis cases, however, in our case the titer of RPR was not remarkably high, which suggests that the high titer of RPR is not always correlated to the occurrence of malignant syphilis. By presenting a variety of clinical manifestations and mimicking several common dermatoses, malignant syphilis should always be included in differential diagnoses, even though it might be rare in the absence of HIV infection. When accompanied by psychological or neurological symptoms, the physician should be alert for the possibility of neurosyphilis, and serological screening for syphilis should be routine for such patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Maher J S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Sharma VK, Kumar B. Malignant syphilis or syphilis simulating malignancy. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cid PM, Cudós ES, Zamora Vargas FX, Merino MJ, Pinto PH. Pathologically confirmed malignant syphilis using immunohistochemical staining: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:94-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Delgado S, Caceres J. Malignant Syphilis in a Human Immunodeficient Virus-Infected Patient. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:523-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sun JR, Tu P, Wang Y. Image Gallery: Malignant syphilis in a young man with HIV infection. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:e392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Requena CB, Orasmo CR, Ocanha JP, Barraviera SR, Marques ME, Marques SA. Malignant syphilis in an immunocompetent female patient. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:970-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rao AG, Swathi T, Hari S, Kolli A, Reddy UD. Malignant Syphilis in an Immunocompetent Adult Male. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:524-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | González-Lara L, Vázquez-López F, Eiris-Salvado N, Pérez-Oliva N. [Malignant syphilis in an immunocompetent patient]. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;140:e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li JH, Guo H, Zheng S, Li B, Gao XH, Chen HD. Widespread Crusted Skin Ulcerations in a Man with Type II Diabetes: A Quiz. Diagnosis: Malignant syphilis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:632-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park SY, Kang JH, Roh JH, Huh HJ, Yeo JS, Kim DY. Secondary syphilis presenting as a generalized lymphadenopathy: clinical mimicry of malignant lymphoma. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:490-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Muylaert B, Almeidinha Y, Borelli N, Esteves E, Oliveira AR, Cestari CM, Garbelini GL, Eid R, Michalany A, De Oliveira Filho J. Malignant syphilis and neurosyphilis in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:AB152. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schöfer H, Imhof M, Thoma-Greber E, Brockmeyer NH, Hartmann M, Gerken G, Pees HW, Rasokat H, Hartmann H, Sadri I, Emminger C, Stellbrink HJ, Baumgarten R, Plettenberg A. Active syphilis in HIV infection: a multicentre retrospective survey. The German AIDS Study Group (GASG). Genitourin Med. 1996;72:176-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | de Carvalho NS, Mello GR, Castro GR, Telles FQ, Reggiani C, Piazza MJ. Malignant syphilis in an HIV seropositive woman. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102:297-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Corti M, Solari R, De Carolis L, Figueiras O, Vittar N, Maronna E. [Malignant syphilis in a patient infected by human immunodeficiency virus. Case report and literature review]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2012;29:678-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | dos Santos TR, de Castro IJ, Dahia MM, de Azevedo MC, da Silva GA, Motta RN, da Cunha Pinto J, de Almeida Ferry FR. Malignant syphilis in an AIDS patient. Infection. 2015;43:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vinay K, Kanwar AJ, Narang T, Saikia UN. Malignant syphilis. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e930-e931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kingston M, French P, Higgins S, McQuillan O, Sukthankar A, Stott C, McBrien B, Tipple C, Turner A, Sullivan AK, Members of the Syphilis guidelines revision group 2015, Radcliffe K, Cousins D, FitzGerald M, Fisher M, Grover D, Higgins S, Kingston M, Rayment M, Sullivan A. UK national guidelines on the management of syphilis 2015. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27:421-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pastuszczak M, Wojas-Pelc A. Current standards for diagnosis and treatment of syphilis: selection of some practical issues, based on the European (IUSTI) and U.S. (CDC) guidelines. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:203-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rajan J, Prasad PV, Chockalingam K, Kaviarasan PK. Malignant syphilis with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2011;2:19-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shao LL, Guo R, Shi WJ, Liu YJ, Feng B, Han L, Liu QZ. Could lengthening minocycline therapy better treat early syphilis? Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |