Published online Aug 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2238

Peer-review started: May 7, 2019

First decision: May 31, 2019

Revised: June 23, 2019

Accepted: July 27, 2019

Article in press: July 27, 2019

Published online: August 26, 2019

Processing time: 123 Days and 17.9 Hours

Muscular atrophy is the basic defect of neurogenic clubfoot. Muscle atrophy of clubfoot needs more scientific and reasonable imaging measurement parameters to evaluate. The Hippo pathway and myostatin pathway may be directly correlated in myogenesis. In this study, we will use congenital neurogenic clubfoot muscle atrophy model to verify in vivo. Further, the antagonistic mechanism of TAZ on myostatin was studied in the C2C12 cell differentiation model.

To identify muscle atrophy in fetal neurogenic clubfoot by ultrasound imaging and detect the expression of TAZ and myostatin in gastrocnemius muscle. To elucidate the possible mechanisms by which TAZ antagonizes myostatin-induced atrophy in an in vitro cell model.

Muscle atrophy in eight cases of fetal unilateral clubfoot with nervous system abnormalities was identified by 2D and 3D ultrasound. Western blotting and immunostaining were performed to detect expression of myostatin and TAZ. TAZ overexpression in C2C12 myotubes and the expression of associated proteins were analyzed by western blotting.

The maximum cross-sectional area of the fetal clubfoot on the varus side was reduced compared to the contralateral side. Myostatin was elevated in the atrophied gastrocnemius muscle, while TAZ expression was decreased. They were negatively correlated. TAZ overexpression reversed the diameter reduction of the myotube, downregulated phosphorylated Akt, and increased the expression of forkhead box O4 induced by myostatin.

Ultrasound can detect muscle atrophy of fetal clubfoot. TAZ and myostatin are involved in the pathological process of neurogenic clubfoot muscle atrophy. TAZ antagonizes myostatin-induced myotube atrophy, potentially through regulation of the Akt/forkhead box O4 signaling pathway.

Core tip: This study aimed to identify muscle atrophy in fetal neurogenic clubfoot, detect expression of TAZ and myostatin in gastrocnemius muscle, and establish the mechanisms through which TAZ antagonizes myostatin-induced atrophy in an in vitro cell model. Muscle atrophy in fetal unilateral clubfoot with nervous system abnormalities was identified by ultrasound. TAZ overexpression in C2C12 myotubes induced atrophy by myostatin. Both TAZ and myostatin are involved in the process of neurogenic clubfoot muscle atrophy, and they are negatively correlated. TAZ antagonizes myostatin-induced myotube atrophy, potentially through regulation of the Akt/forkhead box O4 pathway.

- Citation: Sun JX, Yang ZY, Xie LM, Wang B, Bai N, Cai AL. TAZ and myostatin involved in muscle atrophy of congenital neurogenic clubfoot. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(16): 2238-2246

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i16/2238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2238

Muscle atrophy is the basic defect of clubfoot and is important for functional outcomes[1]. Treatment that targets muscle atrophy is insufficient due to the lack of research on the mechanism of the disease. Muscular atrophy affects a patient’s physical activities and even impairs their cognitive function. Therefore, it is important to explore the pathogenic mechanism and treatment of muscular atrophy.

Although it is still controversial, the occurrence of congenital clubfoot muscle atrophy is thought to be a neuromuscular abnormality[2], and studies have clearly confirmed that the changes in clubfoot muscle atrophy with neuropathy are more dramatic[3-5]. Therefore, the present study investigated patients with clubfoot atrophy with neurological abnormalities by ultrasound examination.

The Hippo signaling pathway plays a crucial role in the process of myogenesis and skeletal muscle regeneration[6,7]. Previous studies have confirmed that TAZ has a positive role in muscle function by upregulating myoD and activating gene transcription of myogenin and MCK[8,9]. Our previous studies showed that upregulation of TAZ in C2C12 cells could enhance the combination of myoD and myogenin promoter, promote myoD-dependent gene transcription, and antagonize the inhibition of muscle differentiation induced by myostatin. These effects were diminished by endogenous knockdown of TAZ[10].

Myostatin, a member of the transforming growth factor-β super family, is specifically expressed in embryonic and adult skeletal muscle and acts as an inhibitor of skeletal muscle protein production and hypertrophy[11,12]. Myostatin has been shown to play an important role in the process of denervation of gastrocnemius atrophy[13]. Myostatin signal transduction is mediated by two different types of serine/threonine kinase receptors. It can transduce signals into the nucleus through SMAD, MAPK, and Akt pathways[14,15].

Our previous studies confirmed the role of TAZ in muscle atrophy in a variety of in vivo models[10,16]. In this study, we confirmed our theory in vivo, using a new model of neurogenic muscular atrophy of congenital clubfoot with nervous system abnormalities and further explored how TAZ acts on myostatin-induced C2C12 myotube atrophy.

Muscle tissue specimens were obtained from eight fetuses that underwent induced abortion due to the prenatal diagnosis of congenital clubfoot combined with nervous system abnormalities in Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University. For better comparison, fetuses with bilateral varus were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University (protocol number 2016PS055K). Ultrasound equipment was Voluson E10 color Doppler ultrasound diagnostic instrument (GE, Boston, MA, United States). The frequency of the conventional abdominal convex probe was 1.0–5.0 MHz.

C2C12 cell line (mouse myoblasts) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, United States). Cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY, United States). Culture medium was supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL), 10 mmol/L HEPES–NaOH (Gibco-BRL), 100 IU/mL penicillin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, United States) and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma). Cells were grown on sterile tissue culture dishes at 37 °C in a humid atmosphere with 5% CO2 and were passaged every 3–4 d using 0.25% trypsin (Gibco-BRL) when the density of cells was around 70%–80%. To induce muscle differentiation, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 2% horse serum for 3 consecutive days when cells grew up to 100% confluence. DMSO (Sigma), 100 ng/mL myostatin (R and D) and 10 mmol/L IBS008738 were added to the medium alone or in combination, and the medium was changed every day. We observed the formation of myotubes under inverted microscope.

TAZ overexpression plasmid and control constructions were synthesized by Bioengineering (Shanghai) Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cells were transfected using the Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent. Following transfection, the protein levels were assessed 48 h later. The cells were cultured to confluence and myotube formation was induced by differentiation medium with DMSO or 100 ng/mL myostatin. Three days later, myotubes were observed and measured.

Total proteins from primary tissues and cell lines were extracted in lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, United States) and quantified using the Bradford method. Fifty micrograms of protein were separated by 12% SDS–PAGE. After transferring, the polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, United States) were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following antibodies TAZ (560235, 1:1000; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States), myostatin (98337, 1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States), Akt (#9272, 1:500; GST), p-Akt (4060S, 1:500; GST), forkhead box (FOX)O4 (#9472, 1:500; GST), and GAPDH (TA-08, 1:500; ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China). After incubation with peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse IgG (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) at 37 °C for 2 h, bound proteins were visualized using Bio-Rad GS-800 and analyzed using Image J software. The relative protein levels were calculated based on GAPDH as the loading control.

Muscle tissue specimens were fixed with 10% neutral formalin, embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm-thick sections were prepared. Immunostaining was performed using the avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex method (Ultra Sensitive TM; Maixin, Fuzhou, China). The sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohol series, and boiled in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 2 min in an autoclave. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using hydrogen peroxide (0.3%), which was followed by incubation with normal goat serum to reduce nonspecific binding. Tissue sections were incubated with antibody to TAZ (560235, 1:100; BD) or myostatin (98337, 1:100; Abcam). Staining for all primary antibodies was performed at 4 °C overnight. Biotinylated goat anti-mouse serum IgG (ready-to-use) (Maixin) was used as the secondary antibody at room temperature for 25 min. After washing three times in phosphate-buffered saline, the sections were incubated with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin–biotin for 20 min, followed by 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride to develop the peroxidase reaction. Counterstaining of the sections was done with hematoxylin and then dehydrated in ethanol before mounting.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using paired-samples t test for comparison between two samples or one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons using GraphPad Prism 5.0. (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, United States). P < 0.05 means the difference was statistically significant.

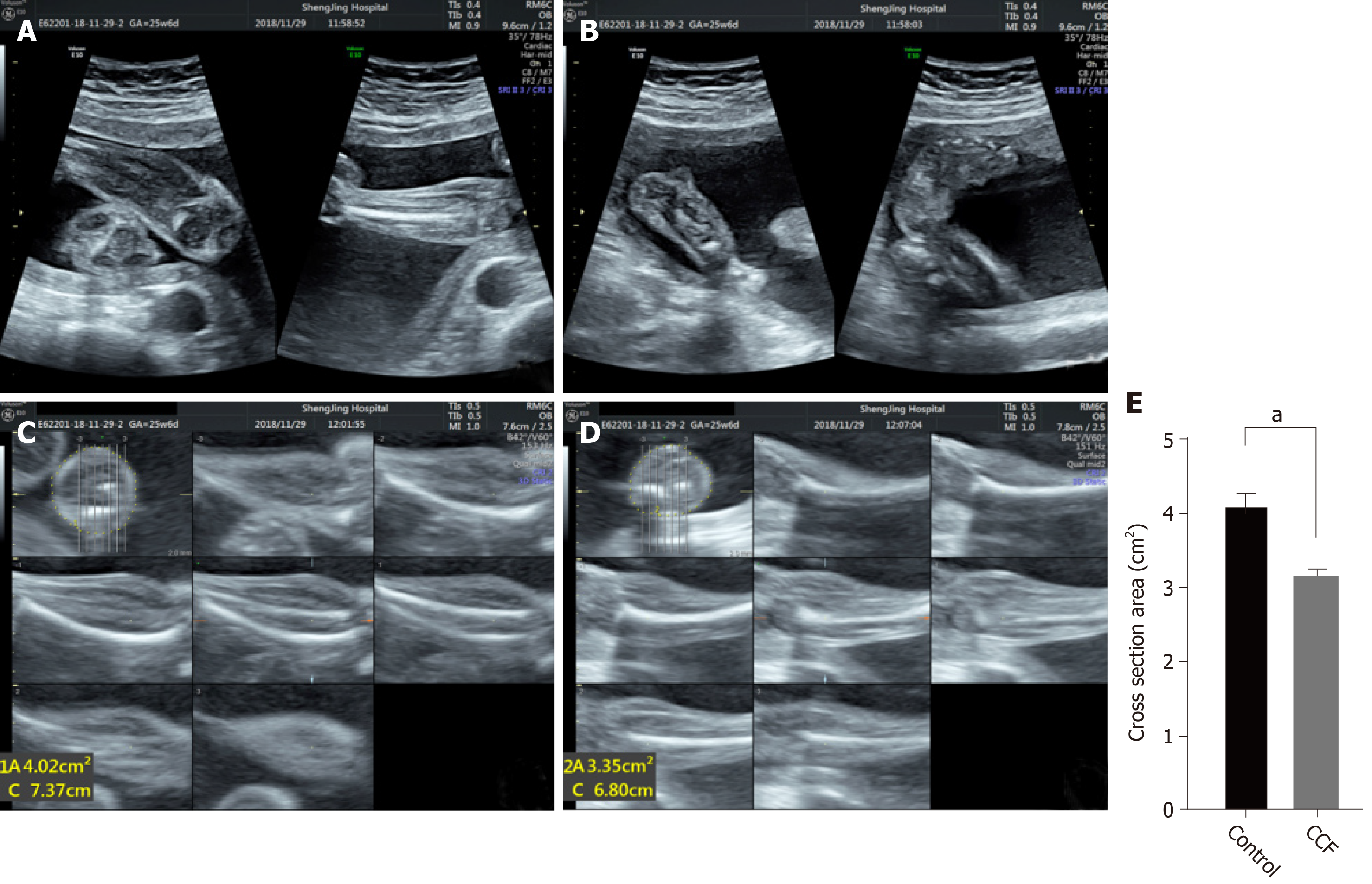

Two-dimensional ultrasound showed the fetal calf and foot, and the inversion side and healthy side images were obtained (Figure 1A and 1B). Ultrasound clearly showed bilateral calf muscles and bones and confirmed clubfoot. Three-dimensional tomographic ultrasound imaging was used to position the largest cross-section perpendicular to the tibia, and the cross-sectional area of bilateral calves was measured (Figure 1C and 1D). Quantitative results showed that the area of the varus side was significantly reduced (Figure 1E), and muscle atrophy was confirmed.

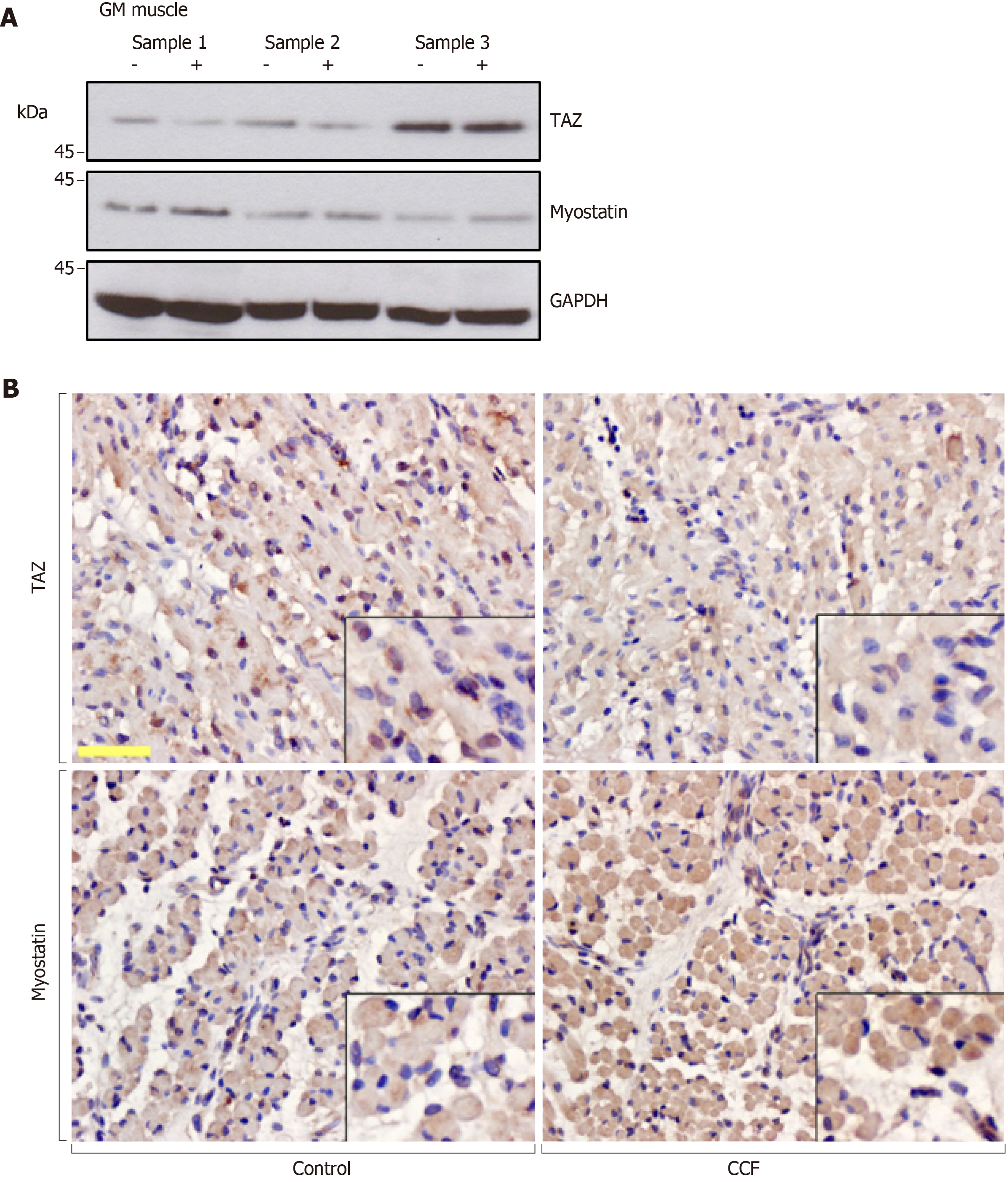

Gastrocnemius muscle tissue specimens were obtained from eight fetuses. We defined the varus limb as a positive experimental group and the normal limb of the same fetus as a negative control group. Western blotting was used to detect the protein levels of endogenous TAZ and myostatin. Western blotting (Figure 2A) and immunostaining (Figure 2B) showed that myostatin was increased in the atrophied gastrocnemius muscle, while TAZ expression was decreased. There was a negative correlation between expression of TAZ and myostatin.

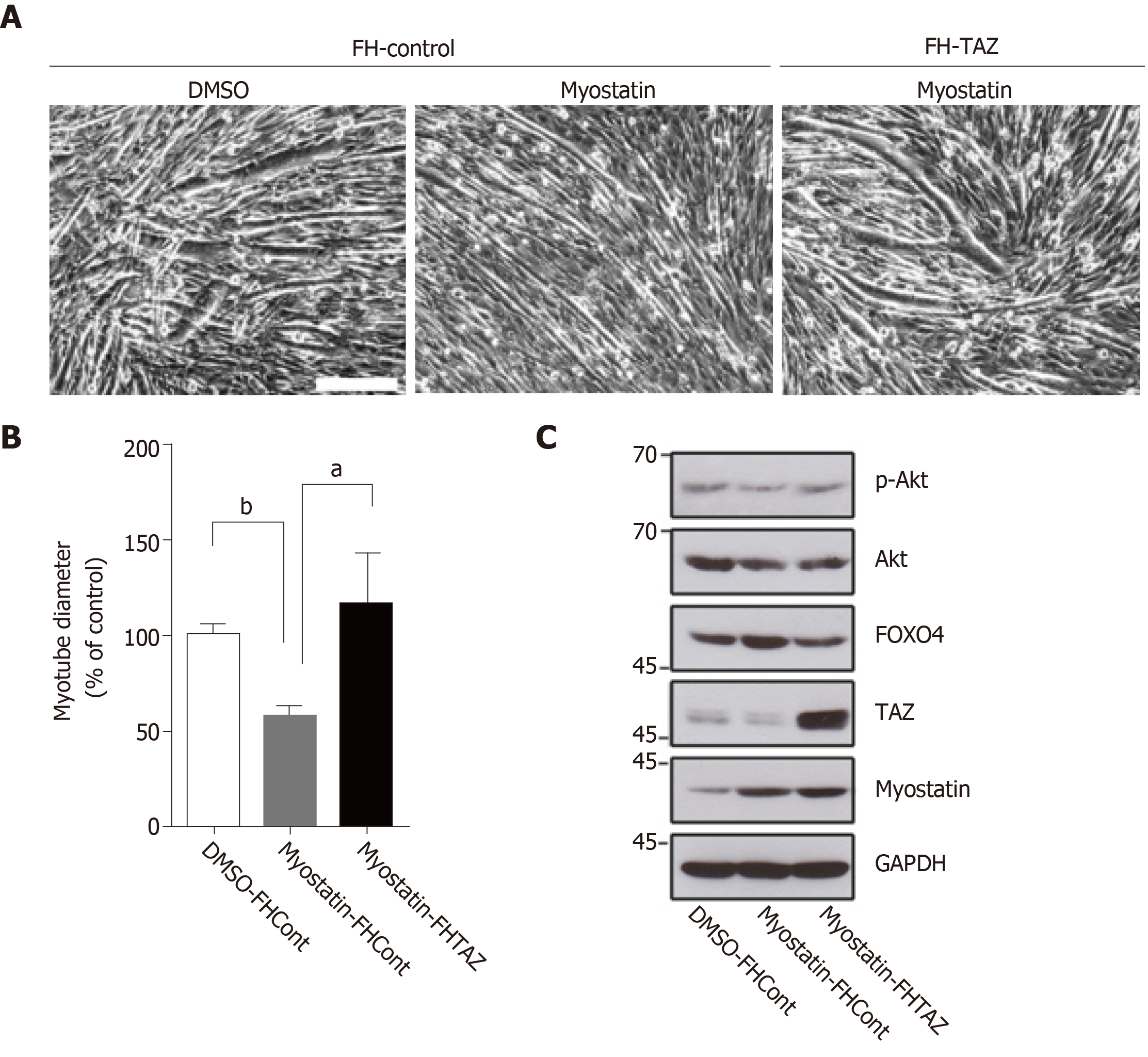

To investigate the interaction between TAZ and myostatin in muscle atrophy, we created TAZ-overexpressing and control C2C12 cells by transfection. We induced myotube atrophy by adding exogenous myostatin. Three days later, photomicrographs and quantitative data showed that myotube diameter in myostatin-treated control cells was smaller than that in DMSO-treated cells (Figure 3A and 3B left two columns), and TAZ overexpression reversed this condition (Figure 3A and 3B right two columns). As a key element that cross talks with myostatin in skeletal muscle atrophy, phosphorylated Akt was expectedly decreased by myostatin treatment, while TAZ recovered it to nearly its original level. FOXO4, a downstream factor of Akt, is also reported to be closely related with clubfoot, but it showed the opposite trend to phosphorylated Akt (Figure 3C).

Previous studies have focused on the use of magnetic resonance after birth to determine the presence of muscle atrophy in clubfoot[17-19]. We first attempted to use ultrasound to prenatally diagnose muscle atrophy. Our results show that combination of 2D and 3D ultrasound can achieve accurate localization, measurement, and quantitative comparison. As it is convenient to operate and there is no radiation, it is the preferred method for prenatal diagnosis of muscle atrophy of fetal clubfoot.

The Hippo pathway is important for regulating differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells, and its downstream cotranscription factor TAZ has been shown to promote muscle differentiation[6,20,21]. However, there are few reports about the relationship between TAZ and myostatin in muscle differentiation. In our previous screening assay, we found that the low molecular weight compound that could activate TAZ had an antagonistic effect on myostatin in a TAZ-dependent manner[10] . This compound has been commercialized as a TAZ activator and muscle differentiation promoter (TAZ activator, IBS008738: Calbiochem; 530961: Merck Millipore). The results encouraged us to further investigate the interaction between the Hippo and myostatin pathways and explore the possibility of TAZ activators as myogenic drugs. The myostatin pathway is a classical inhibitory pathway of muscle differentiation[22-25]. It plays an important role in neurogenic gastrocnemius muscle atrophy, so we chose fetal specimens with abnormal neurological malformation in clubfoot. The myostatin pathway plays its role by interacting with the IGF-1/PI3K, mTOR, and MAPK pathways[26,27]. IGF-1/PI3K/Akt signaling reduces during muscle atrophy induced by denervation, unloading, and joint immobilization[28].

Myostatin inhibits Akt and thereby downregulates mTOR, S6K, and Akt inhibition and protein degradation associated with the FOXO family[27], while FOXO4 is reported to be closely associated with clubfoot[29]. Previous studies have shown that TAZ activators upregulate TAZ and p-Akt in a TAZ-dependent manner (data not shown). Therefore, we speculated that TAZ antagonizes myostatin partially because it reverses the inhibition of Akt by myostatin and the resulting increase of FOXO4.

Our previous studies confirmed that TAZ and its activator promoted muscle differentiation and resisted muscular atrophy, based on in vivo animal models of muscular atrophy induced by toxins, glucocorticoids[10], traumatic brain injury[16], disuse, starvation, and cancer-related cachexia[30]. These results suggest the potential of TAZ activators for treatment of muscle atrophy. In this study we selected gastrocnemius muscle tissue specimens from fetuses with congenital clubfoot. We confirmed that both TAZ and myostatin are involved in the pathological process of neurogenic clubfoot muscle atrophy, and they are negatively correlated. TAZ antagonizes myostatin-induced myotube atrophy, potentially through regulation of the Akt/FOXO4 signaling pathway. We also provide a theoretical basis for further application of TAZ activators in the treatment of neurogenic muscle atrophy.

Muscle atrophy and volume reduction in neurogenic congenital clubfoot are the main factors causing limb mobility disorder, which seriously affects the quality of life of children. The rehabilitation treatment of muscle atrophy has great significance. At present, there are few reports on the study of clubfoot muscle atrophy. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to use effective methods to diagnose and study in-depth mechanism research of clubfoot muscle atrophy.

Until now, the diagnose of clubfoot muscle atrophy is mainly depended on magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound is simple and real-time, and it is more suitable for follow-up prenatal observation and postnatal treatment. Therefore, this study clarifies the diagnostic value of 3D tomographic ultrasound imaging (TUI) for neurogenic congenital clubfoot muscle atrophy. There is no targeted drug treatment for clubfoot muscle atrophy currently, so this study attempts to reveal the mechanism of TAZ involvement in clubfoot muscle atrophy and to find drug therapeutic targets.

The objective of this study was to establish an ultrasound evaluation system for clubfoot muscle atrophy and to reveal the possible mechanisms of TAZ and myostatin involvement in clubfoot muscle atrophy and provide a theoretical basis for the development of potential drug therapy.

Prenatal 2D and 3D ultrasound imaging was used to diagnose fetuses with neurological clubfoot. Quantitative evaluation of muscle atrophy was performed by 3D TUI. Muscle specimens were obtained, and protein expression was determined by western blotting and immunostaining. TAZ overexpressed C2C12 cells were differentiated and treated with myostatin, muscle differentiation of each group was compared quantitatively, and the Akt/FOXO4 signaling pathway expression was detected by western blotting.

The 3D TUI can detect the muscle atrophy on the varus side, which is significantly smaller than the contralateral side. In the gastrocnemius specimens, TAZ and myostatin had opposite expression trends and were negatively correlated. Myostatin inhibited C2C12 muscle differentiation, manifested as thinner myotubes, and was rescued by TAZ overexpression. Overexpressed TAZ reduces the increased p-Akt and FOXO4 expression caused by myostatin.

The 3D TUI technology can be used to evaluate neurogenic clubfoot muscle atrophy. TAZ and myostatin expression are negatively correlated in muscle samples. TAZ antagonizes muscle differentiation inhibition induced by myostatin, and the mechanism may potentially work through repression of the Akt/FOXO4 signaling pathway.

Using 3D ultrasound to evaluate the clubfoot muscle atrophy prenatally and postpartum is effective. Appling previously developed TAZ activators for future research in order to develop new drug therapy of clubfoot muscle atrophy is necessary.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Charco R, Takamatsu S, Tsegmed U S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Bacino CA, Hecht JT. Etiopathogenesis of equinovarus foot malformations. Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57:473-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Basit S, Khoshhal KI. Genetics of clubfoot; recent progress and future perspectives. Eur J Med Genet. 2018;61:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zionts LE. What's New in Idiopathic Clubfoot? J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35:547-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Balasankar G, Luximon A, Al-Jumaily A. Current conservative management and classification of club foot: A review. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2016;9:257-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wallander HM. Congenital clubfoot. Aspects on epidemiology, residual deformity and patient reported outcome. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2010;81:1-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gnimassou O, Francaux M, Deldicque L. Hippo Pathway and Skeletal Muscle Mass Regulation in Mammals: A Controversial Relationship. Front Physiol. 2017;8:190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wackerhage H, Del Re DP, Judson RN, Sudol M, Sadoshima J. The Hippo signal transduction network in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Sci Signal. 2014;7:re4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhu Y, Wu Y, Cheng J, Wang Q, Li Z, Wang Y, Wang D, Wang H, Zhang W, Ye J, Jiang H, Wang L. Pharmacological activation of TAZ enhances osteogenic differentiation and bone formation of adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jeong H, Bae S, An SY, Byun MR, Hwang JH, Yaffe MB, Hong JH, Hwang ES. TAZ as a novel enhancer of MyoD-mediated myogenic differentiation. FASEB J. 2010;24:3310-3320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yang Z, Nakagawa K, Sarkar A, Maruyama J, Iwasa H, Bao Y, Ishigami-Yuasa M, Ito S, Kagechika H, Hata S, Nishina H, Abe S, Kitagawa M, Hata Y. Screening with a novel cell-based assay for TAZ activators identifies a compound that enhances myogenesis in C2C12 cells and facilitates muscle repair in a muscle injury model. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:1607-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen JL, Walton KL, Hagg A, Colgan TD, Johnson K, Qian H, Gregorevic P, Harrison CA. Specific targeting of TGF-β family ligands demonstrates distinct roles in the regulation of muscle mass in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E5266-E5275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schiaffino S, Dyar KA, Ciciliot S, Blaauw B, Sandri M. Mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle growth and atrophy. FEBS J. 2013;280:4294-4314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 832] [Cited by in RCA: 1032] [Article Influence: 86.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ko IG, Jeong JW, Kim YH, Jee YS, Kim SE, Kim SH, Jin JJ, Kim CJ, Chung KJ. Aerobic exercise affects myostatin expression in aged rat skeletal muscles: a possibility of antiaging effects of aerobic exercise related with pelvic floor muscle and urethral rhabdosphincter. Int Neurourol J. 2014;18:77-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Elkina Y, von Haehling S, Anker SD, Springer J. The role of myostatin in muscle wasting: an overview. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2011;2:143-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hulmi JJ, Oliveira BM, Silvennoinen M, Hoogaars WM, Ma H, Pierre P, Pasternack A, Kainulainen H, Ritvos O. Muscle protein synthesis, mTORC1/MAPK/Hippo signaling, and capillary density are altered by blocking of myostatin and activins. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E41-E50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zou R, Li D, Wang G, Zhang M, Zhao Y, Yang Z. TAZ Activator Is Involved in IL-10-Mediated Muscle Responses in an Animal Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Inflammation. 2017;40:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Merrill LJ, Gurnett CA, Siegel M, Sonavane S, Dobbs MB. Vascular abnormalities correlate with decreased soft tissue volumes in idiopathic clubfoot. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1442-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ippolito E, Dragoni M, Antonicoli M, Farsetti P, Simonetti G, Masala S. An MRI volumetric study for leg muscles in congenital clubfoot. J Child Orthop. 2012;6:433-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mahan ST, Yazdy MM, Kasser JR, Werler MM. Prenatal screening for clubfoot: what factors predict prenatal detection? Prenat Diagn. 2014;34:389-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Esteves de Lima J, Bonnin MA, Birchmeier C, Duprez D. Muscle contraction is required to maintain the pool of muscle progenitors via YAP and NOTCH during fetal myogenesis. Elife. 2016;5:e15593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lin KC, Moroishi T, Meng Z, Jeong HS, Plouffe SW, Sekido Y, Han J, Park HW, Guan KL. Regulation of Hippo pathway transcription factor TEAD by p38 MAPK-induced cytoplasmic translocation. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:996-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen JL, Colgan TD, Walton KL, Gregorevic P, Harrison CA. The TGF-β Signalling Network in Muscle Development, Adaptation and Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;900:97-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Consitt LA, Clark BC. The Vicious Cycle of Myostatin Signaling in Sarcopenic Obesity: Myostatin Role in Skeletal Muscle Growth, Insulin Signaling and Implications for Clinical Trials. J Frailty Aging. 2018;7:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Droguett R, Cabello-Verrugio C, Santander C, Brandan E. TGF-beta receptors, in a Smad-independent manner, are required for terminal skeletal muscle differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2487-2503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Babcock LW, Knoblauch M, Clarke MS. The role of myostatin and activin receptor IIB in the regulation of unloading-induced myofiber type-specific skeletal muscle atrophy. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2015;119:633-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hitachi K, Nakatani M, Tsuchida K. Myostatin signaling regulates Akt activity via the regulation of miR-486 expression. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;47:93-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schiaffino S, Mammucari C. Regulation of skeletal muscle growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB pathway: insights from genetic models. Skelet Muscle. 2011;1:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 566] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Timmer LT, Hoogaars WMH, Jaspers RT. The Role of IGF-1 Signaling in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1088:109-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cheng G, Abudurexiti A, Wang L, Wang J, Liu Z, Zhang H, Guo X. Foxo4 gene polymorphism is associated with the risk of talipes equinovarus in Chinese Uyghur. J Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9:3001-3008. |

| 30. | Nagashima S, Bao Y, Hata Y. The Hippo Pathway as Drug Targets in Cancer Therapy and Regenerative Medicine. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18:447-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |