Published online Jun 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i11.1315

Peer-review started: February 15, 2019

First decision: March 14, 2019

Revised: March 27, 2019

Accepted: April 18, 2019

Article in press: April 19, 2019

Published online: June 6, 2019

Processing time: 114 Days and 14.3 Hours

Lupus enteritis is a rare manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Diagnosis of this condition is difficult, especially in the absence of other symptoms related to active SLE. We present the case of a 25-year-old female with lupus enteritis as the sole initial manifestation of active SLE.

A 25-year-old African American female presented to the Emergency Department complaining of diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting for 2 days. Her past medical history was significant for seasonal allergies and family history was pertinent for discoid lupus in her father and SLE in a cousin. The patient’s vital signs on presentation were normal. Her physical exam was remarkable for significant lower abdominal tenderness without guarding or rigidity. A computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed marked circumferential wall thickening and edema of the proximal and mid small bowel predominantly involving the submucosa. Our main differential diagnoses were intestinal angioedema and mesenteric vein thrombosis. However, mesenteric vessels were patent, and laboratory testing for hereditary angioedema showed a normal C1 Esterase Inhibitor level and low C3 and C4 levels. Infectious work-up was negative. Autoimmune tests showed elevated anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) (13.6), anti-Smith antibody, and anti-ribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP) antibody. The patient was diagnosed with SLE enteritis. She was maintained on bowel rest, given intravenous hydration, and started on methylprednisolone 60 mg IV daily. She had significant improvement in her abdominal pain, diarrhea, and emesis after 2 days of treatment. Steroids were tapered and maintained on Hydroxychloroquine with no relapses one year after presentation.

This case of lupus enteritis represents a rare manifestation of SLE. Diagnosis requires clinical suspicion, characteristic imaging and laboratory tests. Endoscopic appearance and biopsies usually yield non-specific findings. High dose steroids are the preferred treatment modality for moderate and severe cases.

Core tip: Lupus enteritis is a rare manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It is a difficult diagnosis, especially in the absence of other symptoms related to active SLE. We present the case of a 25-year-old female with lupus enteritis as the sole initial manifestation of active SLE. The diagnosis can be made with history, physical exam, laboratory testing, and imaging. Endoscopy is not required nor recommended to make the diagnosis. Treatment depends on the severity. In this patient with moderate severity lupus enteritis, high dose steroids were an efficient initial treatment. Hydroxychloroquine was used to maintain remission.

- Citation: Gonzalez A, Wadhwa V, Salomon F, Kaur J, Castro FJ. Lupus enteritis as the only active manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(11): 1315-1322

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i11/1315.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i11.1315

Systematic lupus erythematous (SLE) is an autoimmune disorder affecting about 161000 to 322000 people in the United States[1]. It typically affects multiple organ systems, including the gastrointestinal system. Lupus enteritis, defined as a vasculitis or inflammation of the small bowel, is a rare manifestation of SLE that affects 0.2% to 5.8%[2,3] of these patients. Its diagnosis can be difficult, especially in the absence of other SLE symptoms. To our knowledge, there are only a few case reports mentioning lupus enteritis as the only and initial presentation of active SLE[4-11]. We present the case of a 25-year-old female who presented with non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms that led to the diagnosis of lupus enteritis as the only presenting manifestation of active SLE.

A 25-year-old African American female presented to the Emergency Department (ED) complaining of diffuse abdominal pain, non-bloody diarrhea, nausea, and non-bloody emesis.

The patient’s symptoms started the day prior to arrival to the ED. She described the abdominal pain as sudden onset, sharp and stabbing in quality, 10 out of 10 in intensity, and located in the suprapubic region with radiation to the right and left flanks. She denied any rash (including malar erythema), aphthous ulcers, hematuria, pleuritic chest pain, shortness of breath, or fever. Of note, several months prior, the patient had developed left eyelid swelling non-specific arthralgias (without swelling) of her wrists, fingers, and ankles. Her workup, including autoimmune laboratory tests, was inconclusive at the time. No diagnosis was made. Her arthralgias resolved spontaneously after a few days. She denied any arthralgias at the time of examination. The rest of her review of systems was non-contributory.

Her past medical history was significant for seasonal allergies. Her family history was significant for discoid lupus in her father, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in one of her paternal cousins, and SLE in another paternal cousin.

On presentation, the patient’s vital signs were normal: 36.7 °C, heart rate of 92 bpm, blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, respiratory rate of 18, and oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. Her abdominal exam revealed normal bowel sounds, mild abdominal distention but no lesions, scars, or hernias. There was significant lower abdominal tenderness without guarding or rigidity.

Initial laboratory testing included a complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) (Table 1). The patient had leukopenia with a WBC count of 3.25 k/uL, lymphopenia with an absolute lymphocyte count of 740, and anemia with a hemoglobin level of 11.7 g/dL. The CMP revealed a low albumin of 3.1 but was otherwise normal.

| Value | Result | Reference range |

| White blood cells | 4.26 | 3.70-11.0 k/uL |

| Hemoglobin | 11.4 | 11.5-15.5 g/dL |

| Hematocrit | 33.2 | 36.0%-46.0% |

| Platelet Count | 182 | 15-400 k/uL |

| Sodium | 141 | 136-144 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 4.0 | 3.7-5.1 mmol/L |

| Bicarbonate | 21 | 22-30 mmol/L |

| BUN | 20 | 8-21 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.70 | 0.58-0.96 mg/dL |

| Glucose | 95 | 65-100 mg/dL |

| Total Bilirubin | 0.5 | 0.0-1.5 mg/dL |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 52 | 32-117 U/L |

| ALT | 14 | 7-38 U/L |

| AST | 36 | 13-35 U/L |

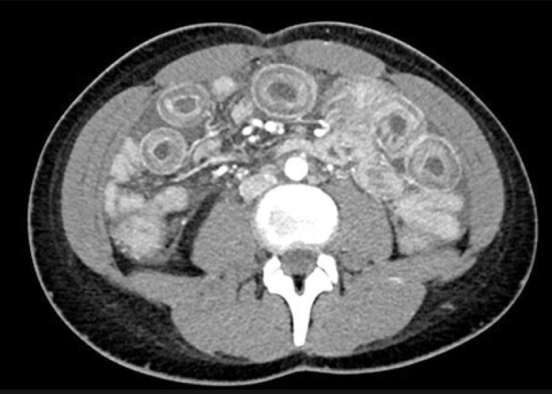

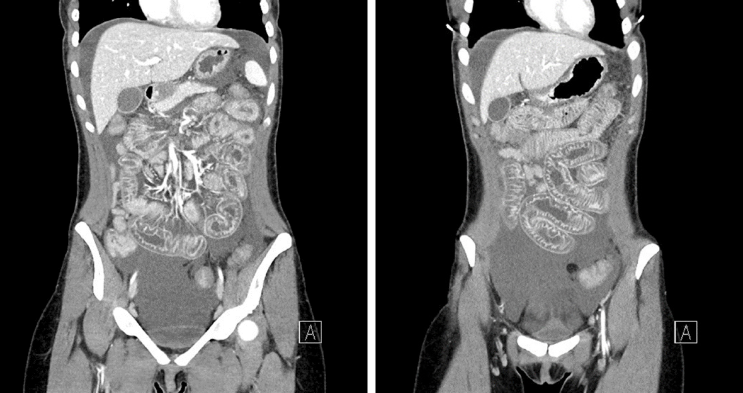

A contrast computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis done in the emergency room revealed marked circumferential wall thickening and edema of the proximal and mid small bowel loops predominantly involving the submucosa (Figures 1 and 2).

At this point, the main differential diagnoses were intestinal angioedema and mesenteric vein thrombosis given the radiographic findings. However, the mesenteric vessels were patent, and there was no evidence of thrombosis. Laboratory testing for hereditary angioedema showed a normal C1 Esterase inhibitor level, low C3 (48 mg/dL), and low C4 (4 mg/dL) (Table 2). Autoimmune work-up revealed elevated ANA of 13.6, normal double stranded DNA antibody of 25 IU/mL (anti-dsDNA ab), high anti-Smith antibody (>8 AI), and high anti-ribonucleic protein of 6.9 AI (anti-RNP) antibody (Table 3). A urinalysis to screen for concomitant lupus nephritis did not show hematuria or red blood cell casts, and a urine protein to creatinine ratio was negative (0.1).

| Laboratory test | Result | Reference range |

| Complement Deficiency Assay | 75 | > 60 Units |

| C1 Esterase Inhibitor Function | 102 | > 40% |

| C1q Complement | 10 | 12-22 mg/dL |

| C1 Esterase Inhibitor | 32 | 21-39 mg/dL |

| C4 | 4.0 | 13-46 mg/dL |

| C3 | 48 | 86-166 mg/dL |

| Laboratory test | Result | Reference range |

| ANA | 13 | None detected |

| Ds-DNA antibody | 25 | < 30 IU/mL |

| Anti-RNP antibody | 6.9 | < 1.0 AI |

| Anti-Smith antibody | > 8.0 | < 1.0 AI |

| C4 | 4.0 | 13-46 mg/dL |

| C3 | 48 | 86-166 mg/dL |

The patient was diagnosed with lupus enteritis.

She was maintained on bowel rest, given intravenous (IV) hydration, and started on methylprednisolone 60 mg IV once daily.

She had significant improvement in her abdominal pain, diarrhea, and emesis after 2 days of treatment. She continued to have some symptoms during evening hours. Her dosing regimen was switched to methylprednisolone 20 mg IV three times daily with improvement of her nighttime symptoms as well. She was discharged on prednisone 75 mg by mouth daily and was tapered off over two weeks. She was transitioned to Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) 200 mg by mouth twice daily. After 12 mo of treatment with HCQ, the patient did not have recurrence of symptoms.

We have presented a rare case of lupus enteritis as the sole initial manifestation of active SLE. Lupus enteritis is seen in only 13% of patients without a previous diagnosis of SLE[12]. To our knowledge, there are only ten previously reported cases in which lupus enteritis was the only initial presentation of active SLE [4-12].

Lupus enteritis presents with very non-specific signs and symptoms, such as abdominal pain (97%), ascites (78%), nausea (49%), vomiting (42%), diarrhea (32%), and fever (20%)[13]. In fact, gastrointestinal activity is not one of the 17 SLICC (Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics) criteria for SLE[14]. SLE patients with gastrointestinal manifestations commonly have a high SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), but our patient denied symptoms of other organ involvement (Table 4). This certainly created diagnostic difficulty, and SLE was initially low on our initial list of differential diagnoses.

| Criteria | Result |

| Acute Rash | No |

| Chronic Rash | No |

| Oral/nasal Ulcers | No |

| Non-scarring Alopecia | No |

| Arthritis | No |

| Serositis | No |

| Abnormal Urine | No |

| Renal | No |

| Neurologic | No |

| Hemolytic Anemia | Yes |

| Leukopenia/Lymphopenia | Yes |

| Thrombocyopenia | No |

| ANA | Yes |

| Anti-dsDNA | No |

| Anti-Sm | Yes |

| Antiphospholipid antibody | No |

| Low Complement | Yes |

Laboratory testing may aid in the diagnosis of lupus enteritis. Our patient had several hematologic (leukopenia, lymphopenia, and anemia) and autoimmune (positive ANA, elevated anti-Smith antibodies, and decreased complement levels) laboratory markers that were consistent with SLE (Tables 2 and 3). Double stranded DNA was negative in her despite being seropositive in 74% of lupus enteritis cases[13]. In comparison, laboratory studies from similar case reports yielded a positive ANA in 100%, a positive ds-DNA in 80%, low complement levels in 70%, and positive anti-Smith antibodies in 20% of cases. Lymphopenia and hypocomplementemia have been shown to correlate with the occurrence of lupus enteritis[4,15]. Interestingly, C-reactive protein is usually not elevated in lupus enteritis[4,13] and was not increased in our case. It is also important to rule out concomitant lupus nephritis, which is present in 65% of all lupus enteritis cases[3] and appears to co-exist in the majority of SLE cases presenting initially with lupus enteritis[16-18]. Screening for lupus nephritis was negative in our patient.

Imaging typically helps establish the diagnosis of lupus enteritis. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with contrast is considered the gold standard[3,13]. Lupus enteritis primarily causes submucosal edema of the jejunum and ileum, leading to classic findings of circumferential bowel wall thickening (known as the “target sign”), dilation of intestinal segments, and engorgement of mesenteric vessels (known as the “comb sign”) (Image 1, 2)[19]. The “target sign”, seen on our patient’s CT scan, is not pathognomonic and may be seen in other conditions such as intestinal angioedema, mesenteric vein thrombosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and intestinal infections[13,19]. In similar case reports, 8 of 10 patients received an abdominal CT scan and all mentioned findings of bowel wall edema, thickening, or the “target sign”. However, most authors[4-8,10] still had difficulty making the correct diagnosis even after obtaining the CT, given its lack of specificity.

Hereditary angioedema was our initial diagnostic impression given her history of allergies and the “target sign” on CT scan, but laboratory values revealed a normal C1 esterase inhibitor (Table 2). Thrombosis was ruled out as the mesenteric vessels were found to be patent. The patient’s negative work-up for mesenteric vein thrombosis and intestinal angioedema, her remote history of nonspecific joint pain, and her family history of lupus prompted us to send autoimmune laboratory testing for SLE. Overall, our patient met five of the 17 criteria needed for SLE diagnosis according to the SLICC criteria (Table 4)[14]. In most other similar case reports, lupus enteritis was not the initial diagnosis, with initial impressions ranging from infectious gastroenteritis[5,8] to acute appendicitis[6].

Endoscopy is usually not helpful nor necessary in making the diagnosis of lupus enteritis since only superficial tissue is analyzed[19,20]. The yield of biopsy is only about 6%[17]. Endoscopy with biopsy should be reserved to confirm or rule out alternative etiologies in cases of diagnostic uncertainty[13]. 56% of patients reported in the literature underwent an endoscopic procedure with biopsy; 1 patient had a colonoscopy[5], 2 patients had an upper endoscopy[7,10], 1 patient had both endoscopy and colonoscopy[4], and 1 patient had a small balloon enteroscopy (SBE). Only the small balloon enteroscopy by Chowichian et al[9] yielded a definitive diagnosis of vasculitis, which re-iterates the fact that endoscopy is of low yield in lupus enteritis. In our case, we did not perform endoscopy and were able to establish a diagnosis and management plan quickly.

There are no prospective controlled studies on the treatment of lupus enteritis, but steroids seem to be the consensus first line treatment[2-18]. According to a 2013 review by Janssens et al[13], the route and dose depends on the severity of abdominal pain and the response to symptoms. Patients with mild abdominal pain tolerating oral intake should receive oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg per day; patients with severe abdominal pain or not tolerating oral intake may receive as high as methylprednisolone 250 mg to 1 g IV daily[13]. Patients who do not respond to pulse dose steroids or have other severe SLE features, such as lupus nephritis, should be treated with IV cyclo-phosphamide or mycophenolate. No published guidelines or recommendations exist for the management of lupus enteritis patients who have moderately severe abdominal pain and are unable to tolerate oral intake, which was the scenario in our case. We were able to control her symptoms with methylprednisolone 60 mg IV daily.

Prognosis is generally excellent for patients with lupus enteritis given its good response to steroids. Nevertheless, it is still imperative to identify and adequately treat this disease manifestation in a timely manner as it can have a mortality of 2.7% [13]. In addition, diagnostic uncertainty can lead to unnecessary invasive and costly procedures, such as appendectomy[6], exploratory laparoscopy[7,12], laparotomy, and SBE[9]. Lupus enteritis is estimated to recur in up to 23% of cases[13], which correlates with a lower cumulative dosage of prednisone and a shorter duration of treatment[21]. It has not been established whether the use of hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate, or azathoprine would prevent recurrences[13]. The patient[7] that was mentioned to have a follow up period of one year without remission did not mention if he was on long-term immunosuppression. Our patient did not have recurrence of lupus enteritis after 12 mo on Hydroxychlororoquine (HCQ). Thus, HCQ may indeed be effective in the long-term prevention of lupus enteritis occurrence.

Lupus enteritis as the sole presenting manifestation of active SLE is very rare. Diagnosis of lupus enteritis requires a combination of high clinical suspicion from symptoms, laboratory testing, and imaging. Diagnosis does not require endoscopy. Treatment depends on the severity. In this patient with moderately severe lupus enteritis, high dose steroids were an efficient initial treatment. Our patient has remained in remission on Hydroxychloroquine.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rothschild BM, Tanaka H S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, Liang MH, Kremers HM, Mayes MD, Merkel PA, Pillemer SR, Reveille JD, Stone JH; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1536] [Cited by in RCA: 1595] [Article Influence: 88.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Koo BS, Hong S, Kim YJ, Kim YG, Lee CK, Yoo B. Lupus enteritis: clinical characteristics and predictive factors for recurrence. Lupus. 2015;24:628-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brewer BN, Kamen DL. Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Disease in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44:165-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin HP, Wang YM, Huo AP. Severe, recurrent lupus enteritis as the initial and only presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in a middle-aged woman. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011;44:152-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mushtaq H, Razzaque S, Ahmed K. Lupus Enteritis: An Atypical Initial Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2018;28:160-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Anoosh F, Shariff R, Ambujakshan D, Nandipati KC, Turner JW, Mandava N. Acute abdomen as initial presentation in a patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Am J Case Rep. 2009;10:55-58. |

| 7. | Seyyedmajidi M, Vafaeimanesh J. Severe, Recurrent Mesenteric Vasculitis as the Initial Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2014;16:55-56. |

| 8. | Shwarzbaum D, Rubinov J, Oikonomou I. P2472 - On target: A rare case of Lupus Enteritis as the initial presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG2017 Meeting Abstracts. Orlando, FL: American College of Gastroenterology. Available from: URL: https://eventscribe.com/2017/wcogacg2017/ajaxcalls/PosterInfo.asp?efp=S1lVTUxLQVozODMy&PosterID=116114&rnd=0.3164736. |

| 9. | Chowichian M, Aanpreung P, Pongpaibul A, Charuvanij S. Lupus enteritis as the sole presenting feature of systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of the literature. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2018;1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chung HV, Ramji A, Davis JE, Chang S, Reid GD, Salh B, Freeman HJ, Yoshida EM. Abdominal pain as the initial and sole clinical presenting feature of systemic lupus erythematosus. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:111-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tu YL, Chen LC, Ou LH, Huang JL. Mesenteric vasculitis as the initial presentation in children with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:251-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stoddard CJ, Kay PH, Simms JM, Kennedy A, Hughes P. Acute abdominal complications of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Surg. 1978;65:625-628. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Janssens P, Arnaud L, Galicier L, Mathian A, Hie M, Sene D, Haroche J, Veyssier-Belot C, Huynh-Charlier I, Grenier PA, Piette JC, Amoura Z. Lupus enteritis: from clinical findings to therapeutic management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, Bruce IN, Isenberg D, Wallace DJ, Nived O, Sturfelt G, Ramsey-Goldman R, Bae SC, Hanly JG, Sánchez-Guerrero J, Clarke A, Aranow C, Manzi S, Urowitz M, Gladman D, Kalunian K, Costner M, Werth VP, Zoma A, Bernatsky S, Ruiz-Irastorza G, Khamashta MA, Jacobsen S, Buyon JP, Maddison P, Dooley MA, van Vollenhoven RF, Ginzler E, Stoll T, Peschken C, Jorizzo JL, Callen JP, Lim SS, Fessler BJ, Inanc M, Kamen DL, Rahman A, Steinsson K, Franks AG, Sigler L, Hameed S, Fang H, Pham N, Brey R, Weisman MH, McGwin G, Magder LS. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677-2686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2816] [Cited by in RCA: 3538] [Article Influence: 272.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee CK, Ahn MS, Lee EY, Shin JH, Cho YS, Ha HK, Yoo B, Moon HB. Acute abdominal pain in systemic lupus erythematosus: focus on lupus enteritis (gastrointestinal vasculitis). Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:547-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee HA, Shim HG, Seo YH, Choi SJ, Lee BJ, Lee YH, Ji JD, Kim JH, Song GG. Panenteritis as an Initial Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2016;67:107-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bodh V, Kalwar R, Sharma R, Sharma B, Mahajan S, Raina R, Jarial A. Lupus enteritis: An uncommon manifestation of systemic lupus erythematous as an initial presentation. J Dig Endosc. 2017;8:134-136. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Patro PS, Phatak S, Zanwar A, Lawrence A. Presumptive Lupus Enteritis. Am J Med. 2016;129:e277-e278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Demiselle J, Sayegh J, Cousin M, Olivier A, Augusto JF. An Unusual Cause of Abdominal Pain: Lupus Enteritis. Am J Med. 2016;129:e11-e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tian XP, Zhang X. Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: insight into pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2971-2977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim YG, Ha HK, Nah SS, Lee CK, Moon HB, Yoo B. Acute abdominal pain in systemic lupus erythematosus: factors contributing to recurrence of lupus enteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1537-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |