Published online Jun 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i11.1282

Peer-review started: January 23, 2019

First decision: March 14, 2019

Revised: April 16, 2019

Accepted: May 2, 2019

Article in press: May 2, 2019

Published online: June 6, 2019

Processing time: 135 Days and 14.7 Hours

Syphilitic myelitis caused by Treponema pallidum is an extremely rare disease. However, symptomatic neurosyphilis, especially syphilitic myelitis, and its clinical features have been infrequently reported. Only a few cases of syphilitic myelitis have been documented. To the best of our knowledge, there are only 19 reported cases of syphilitic myelitis. However, the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy have been still not clear.

To explore the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy on spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

First, we report a patient who suffered from syphilitic myelitis with symptoms of sensory disturbance, with longitudinally extensive myelopathy with "flip-flop sign" on spinal MRI. Second, we performed a literature search to identify other reports (reviews, case reports, or case series) from January 1987 to December 2018, using the PubMed and Web of Science databases with the terms including "syphilis", "neurosyphilis", "syphilitic myelitis", "meningomyelitis", "central nervous system", and "spine". We also summarized the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy.

A total of 16 articles of 20 cases were identified. Sixteen patients presented with the onset of sensory disturbance (80%), 15 with paraparesis (75%), and 9 with urinary retention (45%). Eleven patients had a high risk behavior (55%). Five patients had concomitant human immunodeficiency virus infection (25%). Serological data showed that 15 patients had positive venereal disease research laboratory test (VDRL)/treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPHA), and 17 had positive VDRL/TPHA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Seventeen patients were found to have elevated leukocytosis and protein in CSF. On MRI, 16 patients showed abnormal hyperintensities involved the thoracic spine, 6 involved the cervical spine, and 3 involved both the cervical and thoracic spine. There were 3 patients with the "flip-flop sign". All the patients were treated with penicillin, and 15 patients had a good prognosis.

Our case further raises awareness of syphilitic myelitis as an important complication of neurosyphilis due to homosexuality, especially in developing countries such as China.

Core tip: Syphilitic myelitis is a very rare manifestation of neurosyphilis. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial because it represents a treatable and potentially reversible cause of myelopathy if treated with penicillin. Herein, we report a 25-year-old young man presenting with symptoms of sensory disturbance, due to syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy with "flip-flop sign" on spinal magnetic resonance imaging. Furthermore, we summarized the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy by reviewing the relevant literature. Our study also raises awareness of an important complication of neurosyphilis due to homosexuality. Attention is drawn upon the importance of doing serological tests for syphilis when any atypical neurological disorders are presented.

- Citation: Yuan JL, Wang WX, Hu WL. Clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy on spinal magnetic resonance imaging. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(11): 1282-1290

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i11/1282.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i11.1282

Syphilis is a sexually-transmitted disease caused by Treponema pallidum infection. About 2.1 million pregnant women have active syphilis every year[1]. It is both individual and public health issues due to its direct morbidity, increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and lifelong morbidity especially in low-income countries[2]. It could progress over years through a series of clinical stages and result in irreversible neurological complications without treatment. Syphilis continues to be a major public health problem all over the world.

One-third of patients with early syphilis have the manifestations of the central nervous system, and the recent resurgence in syphilis has seen an accompanying increase in cases of neurosyphilis. It can also affect the brain, brainstem, spinal cord, meninges, nerve roots, and cerebral/spinal vessels[3]. The clinical presentations of neurosyphilis include acute lymphocytic meningitis (acute syphilitic meningitis), stroke (meningovascular syphilis), dementia (general paresis), and/or myelopathy (tabes dorsalis, meningomyelitis, and syringomyelia)[4]. The clinical symptoms of syphilitic meningomyelitis usually develop at between 1 and 30 years after the initial infection[5]. The treatment with penicillin and corticosteroids can diminish the affected lesions with partially reversible changes. However, symptomatic neurosyphilis, especially syphilitic myelitis, and its clinical features have been infrequently reported[6].

Only quite a few cases of syphilitic myelitis have been documented in the reported literature. To the best of our knowledge, there are only 19 reported cases of syphilitic myelitis in the literature[4,7-21]. We herein report a case of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy presenting with the characteristic of "flip-flop sign" on spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We also summarized the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy based on the prior reported literature.

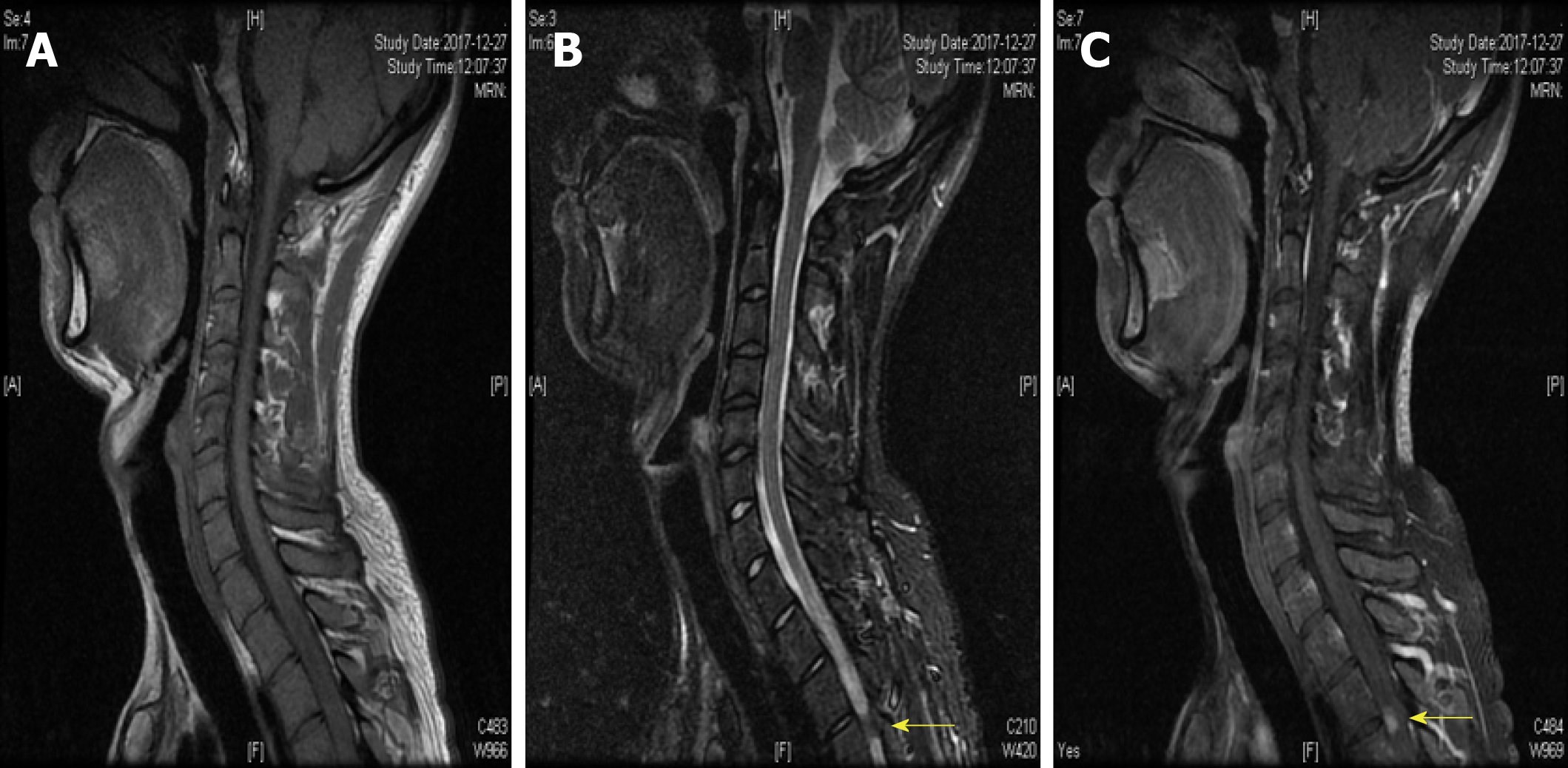

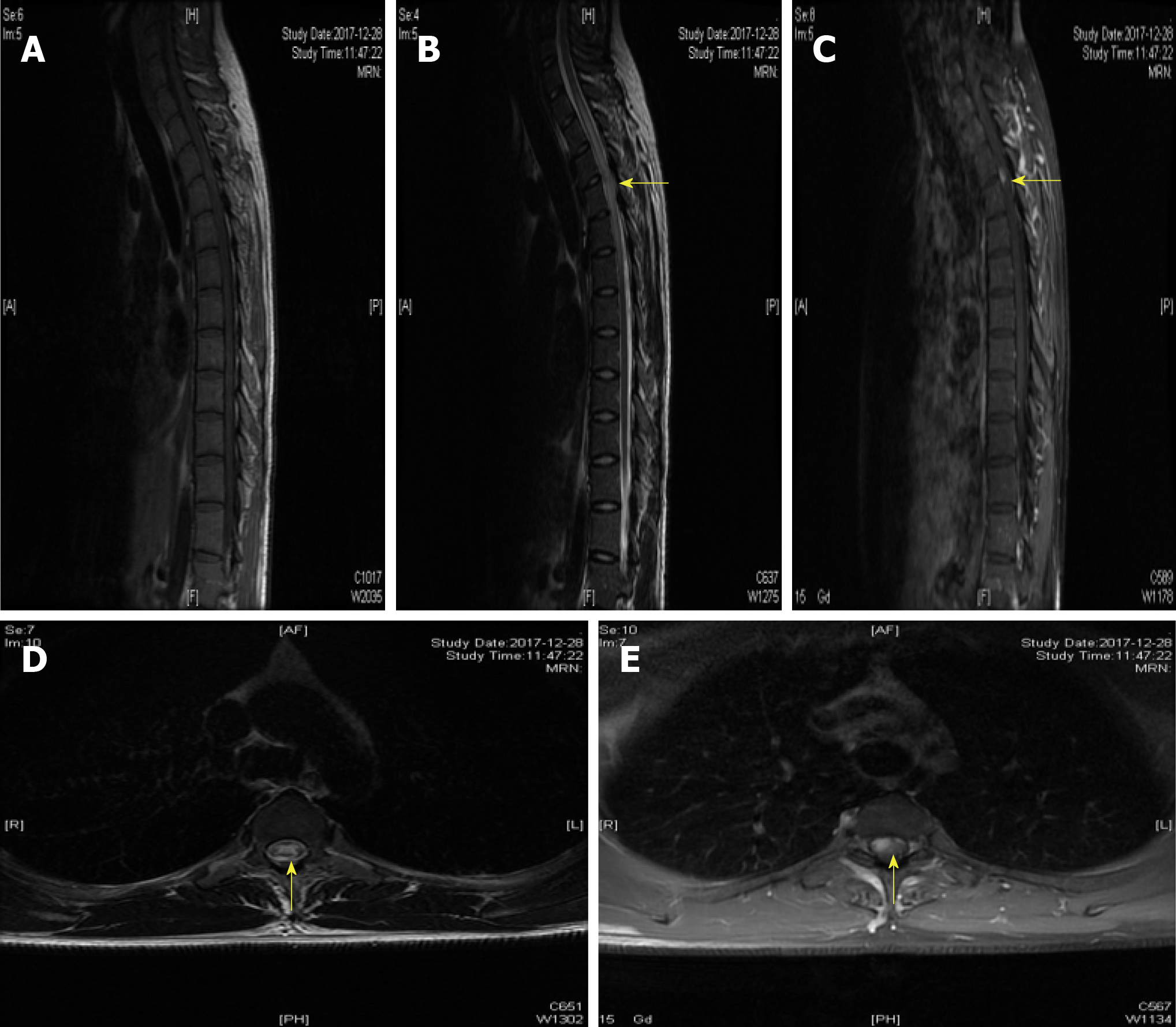

A 25-year-old man was admitted to the Department of Neurology with the symptoms of acute onset of sensory disturbance and numbness for 7 d. He was homosexual and exposed to unprotected intercourse. A neurological examination revealed hypalgesia below the T6 level. The other physical examinations were normal. Laboratory tests revealed the treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) and toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) were positive, and the serum rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was 1:16. The antibody against HIV was negative. The levels of homocysteine, folic acid, and vitamin B12 were 26 μmol/L (0-15 μmol/L), 2.59 ng/mL (>5.4 ng/mL), and 325 pg/mL (211-911 pg/mL), respectively. The results of cerebrospinal fluid test (CSF) showed a higher level of cells (110/μL) and protein (148 mg/dL). The immunological tests of aquaporin 4 (AQP4)-IgG were negative both in serum and CSF. The other inflammatory, immune, and infectious biomarkers both in CSF and serum were also unremarkable. The cranial MRI yielded normal findings. However, the spinal cord MRI showed abnormal longitudinally extensive T2 weighted hyperintensities involving the posterior columns from C7 through T6, with characteristic "flip-flop sign" on cervical spinal MRI (Figure 1B and C, Figure 2B and C). Focal contrast enhancement was observed in the dorsal aspect of the thoracic cord on T1 weighted gadolinium-enhanced images at T3-T4 level (Figures 1C and 2C).

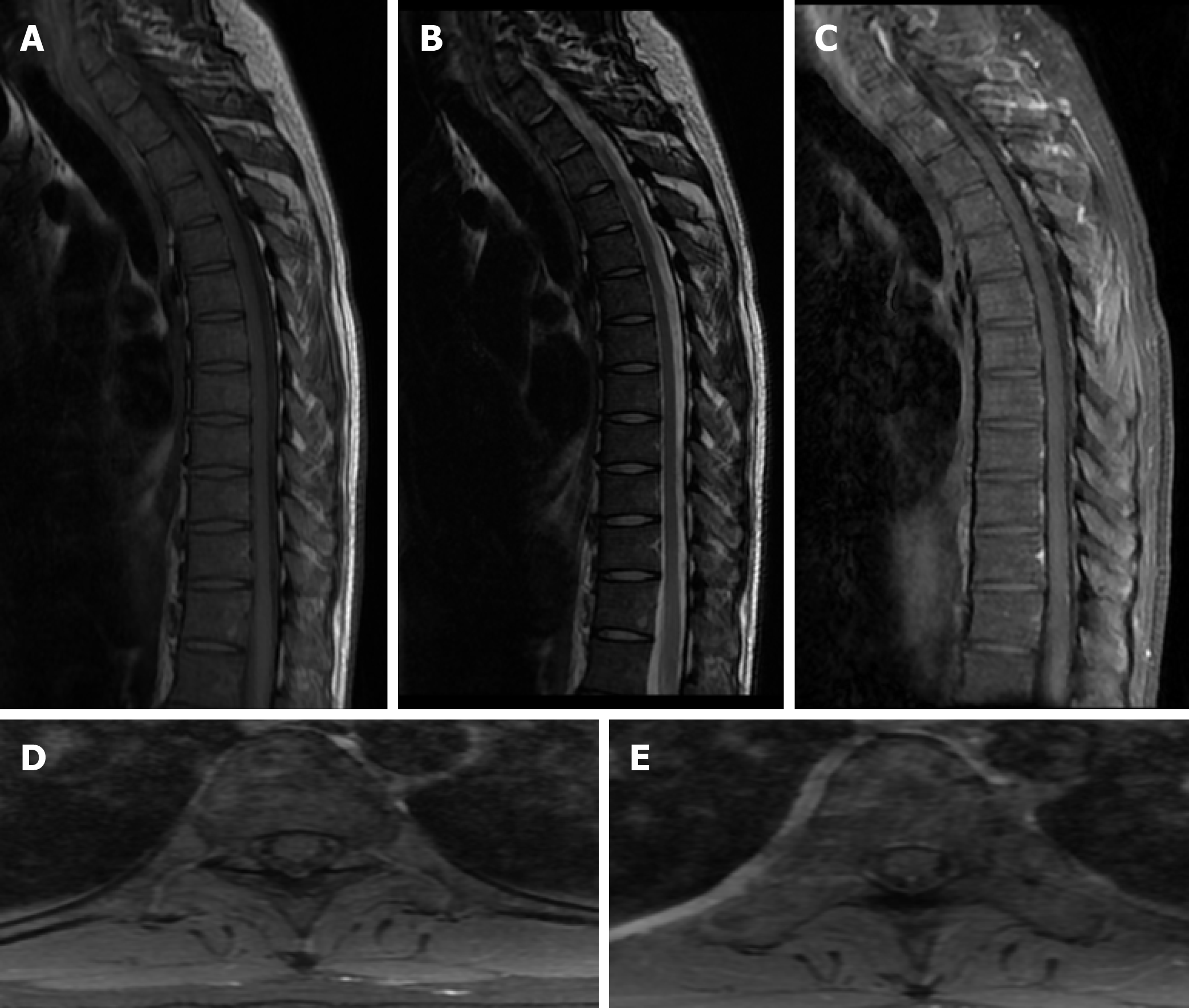

With the treatment of penicillin (24-million IU/d) for 2 weeks, the symptoms of sensation almost disappeared 3 months later. The abnormal hyperintensities of spinal MRI also resolved at the 3-month follow-up (Figure 3). Moreover, the laboratory data of CSF showed reduced cells (24/μL) and protein (65 mg/dL). The findings of TPPA and TRUST (1:8) in serum were still positive. The examination of CSF showed that TPPA was positive and TRUST was 1:1. The diagnosis of syphilitic myelitis was established according to the history of homosexuality, clinical manifestations, MRI findings with typical "flip-flop sign", also with the favorable prognosis after the penicillin treatment.

Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case.

To better understand the clinical characteristics of syphilitic myelitis, we performed a literature search to identify other reports (reviews, case reports, or case series) from January 1987 to February 2019, using the PubMed and web of science databases with the terms including "syphilis", "neurosyphilis", "syphilitic myelitis", "menin-gomyelitis", "central nervous system", and "spine". All pertinent English-language articles were retrieved. A manual search by reviewing the reference sections of the retrieved articles was also performed.

Two investigators collected data from the selected articles. The following data were extracted: the author, country, age, gender, symptoms, neurological examination, etiology, auxiliary examinations, therapy, and outcome. We also summarized the clinical characteristics of this rare disorder.

A total of 16 articles of 20 cases between January 1987 and February 2019 were identified by preliminary literature search. The clinical characteristics of the involved cases are presented in Table 1. Of the 20 patients with syphilitic myelitis, the age of onset varied between 17 and 63 years. Sixteen patients were male (80%). The duration of symptoms was variable from 3 days to 9 months. Sixteen patients presented with the onset of sensory disturbance (80%), 15 with paraparesis (75%), 9 with urinary retention (45%), and 2 with gait disorder (10%). Elven patients had a high risk behavior such as homosexuality or bisexuality (55%). Two patients presented with non-pruritic rash or erythema with the diagnosis of secondary syphilis (10%). One patient was diagnosed with syphilis and had been treated previously (5%). Five patients had concomitant HIV infection (25%). Serological data showed that 15 patients had positive venereal disease research laboratory test (VDRL) and/or high Treponema pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA), and 17 patients had positive VDRL/TPHA in CSF. We also found that the raised protein was seen in 15 patients and pleocytosis was seen in 17 patients in CSF. On MRI, 16 patients showed abnormal signal intensities involving the thoracic spine, 6 involved the cervical spine, and 3 involved both the cervical and thoracic spine. There were 3 patients with the "flip-flop sign". All the patients were treated with penicillin, and 15 patients had a good prognosis.

| Case series | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Ref. | [7] | [8] | [9] | [9] | [10] | [11] | [12] | [13] | [14] | [15] | [16] | [17] | [4] | [18] | [18] | [19] | [20] | [21] | [21] | Our case |

| Age | 46 | 31 | 17 | 29 | 17 | 28 | 63 | 57 | 36 | 46 | 63 | 38 | 32 | 35 | 30 | 49 | 41 | 36 | 49 | 25 |

| Gender | M | M | F | F | M | M | M | F | M | M | M | M | M | M | F | M | M | M | M | M |

| Clinical features | Gait, sensory disturbance, dysuria | Sensory disturbance, paraparesis | Paraparesis, sensory disturbance, urinary retention | Numbness, sensory disturbance, paraparesis | Paraplegia | Chorioretinitis, spastic paraparesis | Sensory deficit, weakness, urinary disturbance | Paraplegia, urinary retention | Pain, paraparesis | Numbness, pain | Pain, weakness | Pain, weakness, numbness, retained urination | Tingling, numbness | Acute transverse myelitis | Acute transverse myelitis | Gait, paresthesia, loss of pain and temperature, urinary retention | Unconscious, numbness | Paresthesia, ascending paresis in inferior limbs | Loss of bilateral strength, sensory impairment | Sensory disturbance, numbness |

| Duration | 2 wk | 10 d | 8 d | 9 mo | NA | 180 d | 60 d | 3 d | 4 mo | 7 d | 12 d | 4 mo | 4 mo | 2 wk | 1 mo | 2 wk | NA | NA | NA | 7 d |

| High risk behavior | NA | + | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | + | + | + | NA | + | + | NA | NA | + |

| HIV infection | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | - |

| Blood VDRL | NA | 1:640 | 1:4 | 1:4 | 1:16 | NA | NA | 1:8 | Reactive | 1:64 | 1:16 | RPR (1:128) | 1:16 | Reactive | Non-reactive | Reactive | RPR+ | NA | NA | TRUST+ RPR (1:16) |

| Blood TPHA | NA | >1:20480 | Reactive | Reactive | FTA-ABS (1:6400) | NA | NA | FTA (3+) TPHA (2+) | 1:5120 | 1:81920 | Reactive | 4+ | 1:160 | 1:5120 | 1:1280 | 1:2560 | + | NA | NA | + |

| CSF protein (mg/dL) | High | 94 | 52 | 54 | 106 | 94 | 200 | Normal | 243 | 72 | 91.70 | 88 | 40 | 123 | 57 | 79 | NA | NA | NA | 148 |

| CSF cells (/μL) | Pleocytosis | 120 | 75 | 20 | 180 | 120 | 498 | Pleocytosis | 346 | 113 | 303 | 18 | 40 | 115 | 170 | 202 | NA | NA | NA | 110 |

| CSF VDRL | Reactive | 1:80 | Non-reactive | Non-reactive | NA | + | + | 1:2 | NA | NA | Reactive | 1:16 | + | Reactive | Reactive | NA | + | NA | NA | NA |

| CSF TPHA | Reactive | 1:5120 | Non-reactive | Reactive | FTA-ABS (1:100) | TPHA+ | NA | NA | FTA-ABS (1:320), TPHA (1:640) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Spinal MRI | High T2 intensity, abnormal Gd-DTPA enhanced | T3/4 wedge-shaped Gd-DTPA enhanced high intensity, swollen spinal cord | Below the C4 diffuse high signal, candle guttering appearance | T1-T11 abnormal signal, flip-flop sign | NA | T6-T8 | LETM, Gadolinium enhancement | Extensive central high T2 signal, enhancement of the dorsal T8-T9 | Diffuse high T2 signal, flip-flop sign | T2-T6 high signal, focal Gd-DTPA enhancement | T6-T11 high signal, focal Gd-DTPA enhancement | Ventral part on the level of T6–T7 | T5-T12 hyperintense signals | Spine-cord edema from D4 to conus medullaris | Spine-cord edema from cervicodorsal up to conus | High-intensity lesions from C4 to T6 | Spinal cord edema from C3-T1 | Signal impairment in the spinal cord (T2-T12) | Diffuse hypersignal at several levels | Longitudinally extensive T2 hyperintensities involving C7 to T6 |

| Treatment | Antibiotic therapy | Penicillin, prednisolone | Penicillin | Penicillin, cephalosporins | Penicillin | Penicillin, dexamethasone | Penicillin, dexamethasone | Antibiotic therapy | Penicillin | Penicillin, methylprednisolone | Ceftriaxone, methylprednisolone | Penicillin, prednisolone | Penicillin | Procaine penicillin, Methyl prednisole | Procaine penicillin, donapezil | Penicillin potassium, methylprednisolone | Penicillin | Penicillin | Penicillin | Penicillin |

| Follow-up duration | NA | 16 d | 14 d | 1 mo | NA | NA | 2 yr | 4 wk | 28 d | 21 d | 30 d | NA | 14 d | 6 mo | Lost | 2 wk | 1 wk | NA | NA | 3 mo |

| Status | Improved | Improved | Complete remission | Improved | Spasticity | NA | Improved | Non improved | Improved | Improved | Improved | Positive effect | NA | Same | NA | Improved | Improved | Complete improvement | Partial improvement | Improved |

| Repeat CSF finding | NA | TPHA (1:2560), VDRL (1:40) | Cells 9/μL, protein 38 mg/dL | NA | Non-reactive | NA | NA | NA | Reduced | N | Cells 34/μL, protein 45.4mg/dL | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | MA | NA | NA | Cells 24/μL, protein 65 mg/dL, TPPA +, TRUST 1:1. |

| Repeat blood finding | NA | TPHA (1:10240), VDRL (1:160) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | VDRL (1:16) | RPR (1:4) | RPR (1:64) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | TPPA (+), TRUST (1:8) |

| Repeat MRI finding | Disappearance of intramedullary high intensity areas | Reduction in the intensity of lesions | Reduction in the intensity of lesions | Reduction in the intensity of lesions | NA | NA | NA | Disappearance of the high signal lesion on T2-weighted images | Gadolinium enhancement disappeared, the high signal intensity diminished | NA | Reduction in the intensity of lesions | NA | NA | NA | NA | Reduction in the size of the cervical and thoracic cord lesions | NA | NA | NA | Dissolved with three months' follow up |

Syphilitic myelitis caused by Treponema pallidum is an extremely rare disease. Herein, we report a rare case in a 25-year-old young man presenting with symptoms of sensory disturbance, due to syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy with typical "flip-flop sign" on spinal MRI. Furthermore, we also summarized the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy.

In the pre-antibiotic era, syphilis was one of the most frequent causes of myelopathy[22]. Syphilitic meningomyelitis represents less than 3% of neurosyphilitic cases. The diagnosis is based on a high CSF white blood cell count (≥ 20 mL) with either a reactive CSF VDRL test or a positive CSF antibody[15]. Syphilitic myelitis is a very rare but not well-recognized manifestation of neurosyphilis. It is a form of meningo-vascular syphilis with abnormalities confined to the spinal cord. The patients can present with sensory disturbance, lower extremity weakness, pyramidal signs, and variable degrees of bladder and bowel dysfunction. Diagnosis is difficult as it may mimic idiopathic transverse myelitis, spinal cord infarction, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD). On spinal MRI, longitudinally extensive myelopathy is common, especially the feature of "flip-flop sign". Our case further suggested that the presence of “flip-flop sign” may indicate syphilitic myelitis.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted and systemic disease, and the most common mechanism of transmission is sexual intercourse. HIV and syphilis affect similar patient groups and co-infection is common. The neurological complications of both infections occasionally occur during a clinical course. In the United States, 16% of all syphilis patients, and 28% of male syphilis patients were co-infected with HIV[23]. If syphilis is detected in a patient with an elevated CSF TPHA-albumin index, it is crucial to check for serum HIV antibodies. As for our finding, 11 (55%) patients had a high risk behavior, such as homosexual and/or bisexual individuals. Five patients had concomitant HIV infection (25%). Determining which of the infections, syphilis or HIV, is crucial for allowing for a prompt diagnosis and the initiation of appropriate treatment. Our case further raised the importance of the serious consequences of homosexuality or high risk of unprotected sexual intercourse.

Although there are several hypotheses, the exact origin of the disease remains unknown[24], which may be due to reversible edema from infection or ischemia[13]. In syphilitic myelitis, there is primary involvement of the meninges and vessels. It is pathologically characterized by meningeal inflammation and spinal cord ischemia and edema due to syphilitic vasculopathy. The MRI abnormalities of the spinal cord probably result from meningeal inflammation and spinal cord ischemia. Spinal cord lesions which have resolved completely following treatment have been reported, and the disappearance of high-signal lesion may indicate that ischemic or inflammatory changes are reversible[13]. As for our case, the high intensity areas on T2-weighted imaging may indicate reversible ischemic change or inflammation[7].

The strengths of our case are listed as follows. First, our case revealed extensive T2-weighted abnormal signals in the spinal cord with "flip-flop sign". To the best of our knowledge, only two cases have been previously described of such longitudinally extensive T2-weighted hyperintensities with "flip-flop sign"[9,14]. Thus, the technique of MRI could be of great importance to explore such disorders[25]. Second, the medical history of homosexuality, clinical presentations, physical examination, laboratory examinations of serum and CSF, imaging findings of "flip-flop sign", good effect of penicillin, and favorable prognosis all contributed to our diagnosis of syphilitic myelitis. Moreover, in view of the longitudinally extensive myelopathy on MRI, we also tested AQP4 both in CSF and serum timely. The results were negative, and the misdiagnosis of NMOSD was avoided. Third, to date, our study is the largest study to explore the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy on spinal MRI.

In summary, syphilitic myelitis is a very rare manifestation of neurosyphilis. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial because it represents a treatable and potentially reversible cause of myelopathy with penicillin. Our study also raises awareness of an important complication of neurosyphilis due to homosexuality. Attention is drawn upon the importance of doing serological tests for syphilis when any atypical neurological situation is presented.

Syphilitic myelitis caused by Treponema pallidum is an extremely rare disease. However, symptomatic neurosyphilis, especially syphilitic myelitis, and its clinical features have been infrequently reported.

Only a few cases of syphilitic myelitis have been documented in the international literature. To the best of our knowledge, there are only 19 reported cases of syphilitic myelitis in the literature.

Our study was aimed to summarize the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy.

First, we report a patient who suffered from syphilitic myelitis with symptoms of sensory disturbance, with longitudinally extensive myelopathy with "flip-flop sign" on spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This patient experienced complete clinical and radiologic recovery after treatment. Second, we summarized the clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy.

A total of 16 articles of 20 cases were identified. Sixteen patients presented with the onset of sensory disturbance (80%), 15 with paraparesis (75%), and 9 with urinary retention (45%). Eleven patients had a high risk behavior (55%). Five patients had concomitant HIV infection (25%). Serological data showed that 15 patients had positive venereal disease research laboratory test (VDRL)/treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPHA), and 17 patients had positive VDRL/TPHA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Seventeen patients had elevated cells and protein in CSF. On MRI, 16 patients showed abnormal signal intensities involving the thoracic spine, 6 involved the cervical spine, and 3 involved both cervical and thoracic spine. There were 3 patients with the "flip-flop sign". All the patients were treated with penicillin, and 15 patients had a good prognosis.

Our case raises awareness of syphilitic myelitis as an important complication of neurosyphilis due to homosexuality, especially in developing countries.

Attention is drawn upon the importance of doing serological tests for syphilis when any atypical neurological situation is presented. A high index of suspicion is necessary so that this potentially treatable disease would not be overlooked.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El-Razek AA S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Hawkes S, Matin N, Broutet N, Low N. Effectiveness of interventions to improve screening for syphilis in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:684-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hook EW. Syphilis. Lancet. 2017;389:1550-1557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Berger JR, Dean D. Neurosyphilis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;121:1461-1472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Srivastava T, Thussu A. MRI in syphilitic meningomyelitis. Neurol India. 2000;48:196-197. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bhai S, Lyons JL. Neurosyphilis Update: Atypical is the New Typical. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17:481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | O'donnell JA, Emery CL. Neurosyphilis: A Current Review. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2005;7:277-284. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Nabatame H, Nakamura K, Matuda M, Fujimoto N, Dodo Y, Imura T. MRI of syphilitic myelitis. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:105-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Tashiro K, Moriwaka F, Sudo K, Akino M, Abe H. Syphilitic myelitis with its magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) verification and successful treatment. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1987;41:269-271. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lu H, Jiao L, Liu Z, Wang B. The syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy:two cases report and literature review. Zhonghua Shenjingke Zazhi. 2016;49:967-969. |

| 10. | Janier M. Acute syphilitic myelitis in a young man. Genitourin Med. 1988;64:206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Strom T, Schneck SA. Syphilitic meningomyelitis. Neurology. 1991;41:325-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jacquemin GL, Proulx P, Gilbert DA, Albert G, Morcos R. Functional recovery from paraplegia caused by syphilitic meningomyelitis. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tsui EY, Ng SH, Chow L, Lai KF, Fong D, Chan JH. Syphilitic myelitis with diffuse spinal cord abnormality on MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2973-2976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kikuchi S, Shinpo K, Niino M, Tashiro K. Subacute syphilitic meningomyelitis with characteristic spinal MRI findings. J Neurol. 2003;250:106-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chilver-Stainer L, Fischer U, Hauf M, Fux CA, Sturzenegger M. Syphilitic myelitis: rare, nonspecific, but treatable. Neurology. 2009;72:673-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | He D, Jiang B. Syphilitic myelitis: magnetic resonance imaging features. Neurol India. 2014;62:89-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Matijosaitis V, Vaitkus A, Pauza V, Valiukeviciene S, Gleizniene R. Neurosyphilis manifesting as spinal transverse myelitis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2006;42:401-405. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kayal AK, Goswami M, Das M, Paul B. Clinical spectrum of neurosyphilis in North East India. Neurol India. 2011;59:344-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tohge R, Shinoto Y, Takahashi M. Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis and Optic Neuropathy Associated with Syphilitic Meningomyelitis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Intern Med. 2017;56:2067-2072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Siu G. Syphilitic Meningomyelitis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2017;117:671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Borges CR, Almeida SM, Sue K, Koslyk JLA, Sato MT, Shiokawa N, Teive HAG. Neurosyphilis and ocular syphilis clinical and cerebrospinal fluid characteristics: a case series. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2018;76:373-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Berger JR, Sabet A. Infectious myelopathies. Semin Neurol. 2002;22:133-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zetola NM, Engelman J, Jensen TP, Klausner JD. Syphilis in the United States: an update for clinicians with an emphasis on HIV coinfection. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1091-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Breitenfeld D, Kust D, Breitenfeld T, Prpić M, Lucijanić M, Zibar D, Hostić V, Franceschi M, Bolanča A. Neurosyphilis in Anglo-American Composers and Jazz Musicians. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56:505-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Razek AAKA, Ashmalla GA. Assessment of paraspinal neurogenic tumors with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:841-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |