Published online May 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i10.1213

Peer-review started: January 25, 2019

First decision: March 9, 2019

Revised: March 17, 2019

Accepted: March 26, 2019

Article in press: March 26, 2019

Published online: May 26, 2019

Processing time: 123 Days and 1.9 Hours

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a type of fatal tumor that is increasing in prevalence. While these are unpleasant facts to consider, it is vitally important to be informed, and it is important to catch the disease early. Typically, lung cancer does not show severe clinical symptoms in the early stage. Once lung cancer has progressed, patients might present with classical symptoms of respiratory system dysfunction. Thus, the prognosis of SCLC is closely related to the early diagnosis of the disease. Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) syndrome (EAS) is related to cancer occurrence, especially for SCLC with the presence of Cushing's syndrome, which is dependent on markedly elevated ACTH and cortisol levels.

In the current report, we describe two middle-age patients who were originally diagnosed with diabetes mellitus with no classical symptoms of lung cancer. The patients were eventually diagnosed with SCLC, which was confirmed by bronchoscopic biopsy and histopathology. SCLC-associated diabetes was related to EAS, which was an endogenous ACTH-dependent form of Cushing’s syndrome with elevated ACTH and cortisol levels. Multiple organ metastases were found in Patient 1, while Patient 2 retained good health at 2 years follow-up. EAS symptoms including thyroid dysfunction, hypercortisolism and glucose intolerance were all resolved after anticancer treatment.

In conclusion, SCLC might start with diabetes mellitus and increased cortisol and hypokalemia or other EAS symptoms. These complex clinical features were the most significant factors to deteriorate a patient’s condition. Early diagnosis and treatment from clinicians were essential for the anti-cancer treatment for patients with SCLC.

Core tip: Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a fatal tumor that is increasing in prevalence. Prognosis of patients with SCLC is closely related to early diagnosis. We report two middle-aged patients who were originally diagnosed with diabetes mellitus with no classical symptoms of lung cancer. Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome symptoms including thyroid dysfunction, hypercortisolism, and glucose intolerance, which are related to elevated adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol levels, were all normal after anticancer treatment. Our findings highlight that SCLC might start with diabetes mellitus and increased cortisol level and hypokalemia or other ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome symptoms, and it reminds clinicians of the importance of early diagnosis of SCLC with ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome.

- Citation: Zhou T, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu Y, Wang YX, Gang XK, Wang GX. Small cell lung cancer starting with diabetes mellitus: Two case reports and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(10): 1213-1220

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i10/1213.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i10.1213

Lung cancer (LC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer, and its prognosis has not improved in recent years[1-5]. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC), accounting for 12%–19% of LC cases, is a fatal tumor that is increasing in prevalence[6]. Despite high sensitivity to chemotherapy, SCLC still has a poor long-term outcome due to shortened cell doubling time, frequent relapse and earlier metastasis[7-10]. Thus, to diagnose SCLC as soon as possible is key to its treatment. In order to attain the above goal, it is critical to differentiate early manifestations of SCLC from other related diseases. The majority of SCLCs express a neuroendocrine program, which is related to ectopic adreno-corticotropic hormone (ACTH) syndrome (EAS)[11,12]. EAS is an endogenous ACTH-dependent form of Cushing’s syndrome that is associated with markedly increased ACTH and cortisol levels. EAS accounts for 5%–10% of all patients presenting with ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism, while SCLC and neuroendocrine tumors account for the majority of such cases[13]. LC typically displays respiratory symptoms. Beyond that, the features of EAS can help to differentiate SCLC from other tumors to some extent. However, there are few case reports on the other manifes-tations of SCLC as early diagnostic clues, which can help clinicians catch the disease at an early stage.

In this paper, we present two cases of SCLS admitted with newly-onset diabetes mellitus but without the classical symptoms of LC or Cushing’s syndrome. Rapid socioeconomic development has led to a dramatic increase in the prevalence of diabetes[14,15]. Thus, diagnosis of diabetes seems to be easier than before. Through the two cases, we draw clinical attention to the fact that diabetes might be an initial symptom of SCLC. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical factors that might influence prognosis of the patients.

Chief complaints: A 50-year-old man presented with aggravating thirst, diuresis, blurred vision, and significant weight loss for 1 mo.

History of present illness: One month before admission, the patient suffered from aggravating thirst, diuresis, blurred vision, and significant weight loss of 5 kg in 1 mo. No fever and other symptoms were present during onset of the illness.

History of past illness: The patient had a history of hypertension. The patient has been smoking for 20 years at a rate of 15 cigarettes daily. He also had a family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Physical examination: Physical examination found that blood pressure was 200/100 mmHg, heart rate was 86 beats/min, body temperature was 36.3 °C, and body mass index (BMI) was 25.93 kg/m2. Sporadic chromatosis and mild edema were found in the lower limbs. The rest of the physical examination was normal.

Laboratory testing: The laboratory tests showed elevated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (8.2%), urine glucose (3+), 8-hr ACTH (36.89 pmol/L), 8-hr cortisol (1027.56 nmol/L) and 24-hr urinary free cortisol (12221 nmol). The laboratory results also showed decreased level of serum K+ (2.18 mmol/L), Na+ (135 mmol/L), Cl− (94.9 mmol/L) and Ca2+ (1.84 mmol/L). Concentrations of urine Na+ (339.5 mmol/24 hr) and Cl− (300 mmol/24 hr) were increased. Thyroid function results showed decreased levels of free tri-iodothyronine (2.4 pmol/L) and free thyroxine (10.21 pmol/L). Dexamethasone-suppression test showed that there was no suppression of ACTH and cortisol secretion. These results are shown in Table 1.

| Items | Test result | Normal range | |

| HbA1c | 8.2% | < 6.5% | |

| γ-GT | 65.0 U/L | 5.0–54.0 U/L | |

| Serum ions | K+ | 2.2 mmol/L | 3.5–5.5 mmol/L |

| Na+ | 135.0 mmol/L | 137–145 mmol/L | |

| Cl+ | 94.9 mmol/L | 98–107 mmol/L | |

| Ca2+ | 1.8 mmol/L | 2.1–2.55 mmol/L | |

| Urine glucose | 3 + | Negative | |

| Thyroid function | TSH | 0.6 μIU/mL | 0.27–4.2 μIU/mL |

| FT3 | 2.4 pmol/L | 3.1–6.8 pmol/L | |

| FT4 | 10.2 pmol/L | 12.0–22.0 pmol/L | |

| ACTH, 8 hr | 36.9 pmol/L | 1.6–13.9 pmol/L | |

| Cortisol, 8 hr | 1027.6 nmol/L | 240–619 nmol/L | |

| 24-hr UFC | 12221.0 nmol | 108–961 nmol/L | |

| Urine | K+ | 74.0 mmol/24 hr | 51–102 mmol/24 hr |

| Na+ | 339.5 mmol/24 hr | 130–260 mmol/24 hr | |

| Ca2+ | 7.5 mmol/24 hr | 2.5–7.5 mmol/24 hr | |

| Cl− | 300.0 mmol/24 hr | 100–250 mmol/24 hr | |

| Dexamethasone-suppression test, at overnight, low-dose and high-dose | No suppression | Suppressed | |

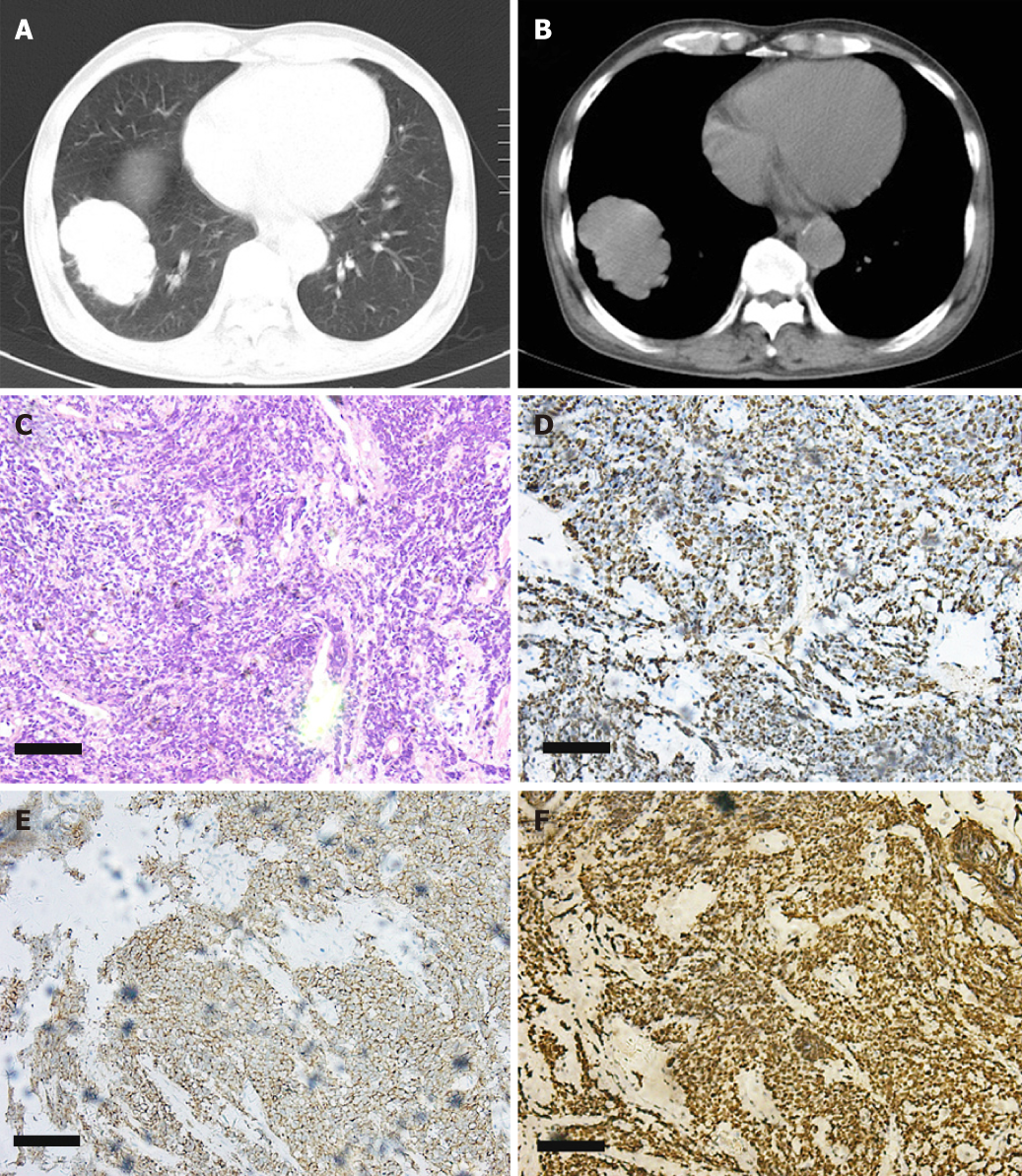

Imaging examination: Findings on laboratory evaluation raised the suspicion of ectopic ACTH secretion that may have originated from SCLC. The conjecture was confirmed by chest X-ray and biopsy (cT2aN3M0). X-rays showed the following: (1) right middle lobe: peripheral LC with lymph node metastasis and distal obstructive pneumonia; and (2) bilateral pleural effusion. Bronchoscopic biopsy showed SCLC. Immunohistochemistry showed: Ki-67 (+ 80%), thyroid transcription factor-1 (+), CD56 (+), Synaptophysin (+). These results are shown in Figure 1. Adrenal gland computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral adrenal stroma, and pituitary magnetic resonance imaging showed nothing abnormal.

Chief complaints: A 54-year-old woman presented with elevated blood glucose concentration for 3 d before physical examination.

History of present illness: Three days before admission, the patient showed blood glucose elevation at physical examination without obvious clinical manifestations. Her weight loss was 2 kg in 1 mo and she felt slight weakness.

History of past illness: Hypertension (140/100 mmHg) was found at physical examination. The patient had a family history of diabetes mellitus and was an active smoker of 40 cigarettes daily.

Physical examination: Physical examination showed body temperature was 36.5 °C, blood pressure 130/98 mmHg, heart rate 89 beats/min, and BMI 21.37 kg/m2. Systemic examination was normal.

Laboratory examination: The laboratory tests showed elevated hemoglobin A1c (9.4%), urine glucose (1 +), fasting glucose (11.2 mmol/L), 8-hr ACTH (167.1 pmol/L), 8-hr cortisol (> 1710.49 nmol/L) and 24-h urinary free cortisol (12762.25 nmol). The laboratory results also showed decreased level of serum K+ (2.45–3.25 mmol/L) and Ca2+ (1.72–1.94 mmol/L). Thyroid function results showed decreased levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (0.039 μIU/mL), free tri-iodothyronine (2.8 pmol/L) and free thyroxine (11.72 pmol/L). These results are shown in Table 2.

| Items | Test result | Normal range | |

| HbA1c | 9.4% | < 6.5% | |

| Fasting glucose | 11.2 mmol/L | 3.9–6.1 mmol/L | |

| blood routine | NE % | 0.8 | 0.5–0.7 |

| RBC | 3.97×1012/L | 4.0×1012–5.5×1012/L | |

| HGB | 111.0 g/L | 120–160 g/L | |

| Urine glucose | 1 + | Negative | |

| Thyroid function | TSH | 0.04 μIU/mL | 0.27–4.2 μIU/mL |

| FT3 | 2.8 pmol/L | 3.1–6.8 pmol/L | |

| FT4 | 11.7 pmol/L | 12.0–22.0 pmol/L | |

| Ion, serum | K+ | 2.5–3.3 mmol/L | 3.5–5.5 mmol/L |

| Ca2+ | 1.7–1.9 mmol/L | 2.1–2.55 mmol/L | |

| ACTH, 8 hr | 167.1 pmol/L | 1.6–13.9 pmol/L | |

| Cortisol, 8 hr | > 1710.5 nmol/L | 240–619 nmol/L | |

| 24-h UFC | 12762.3 nmol/L | 108–961 nmol/L | |

| CEA | 5.6 ng/mL | < 5 ng/mL | |

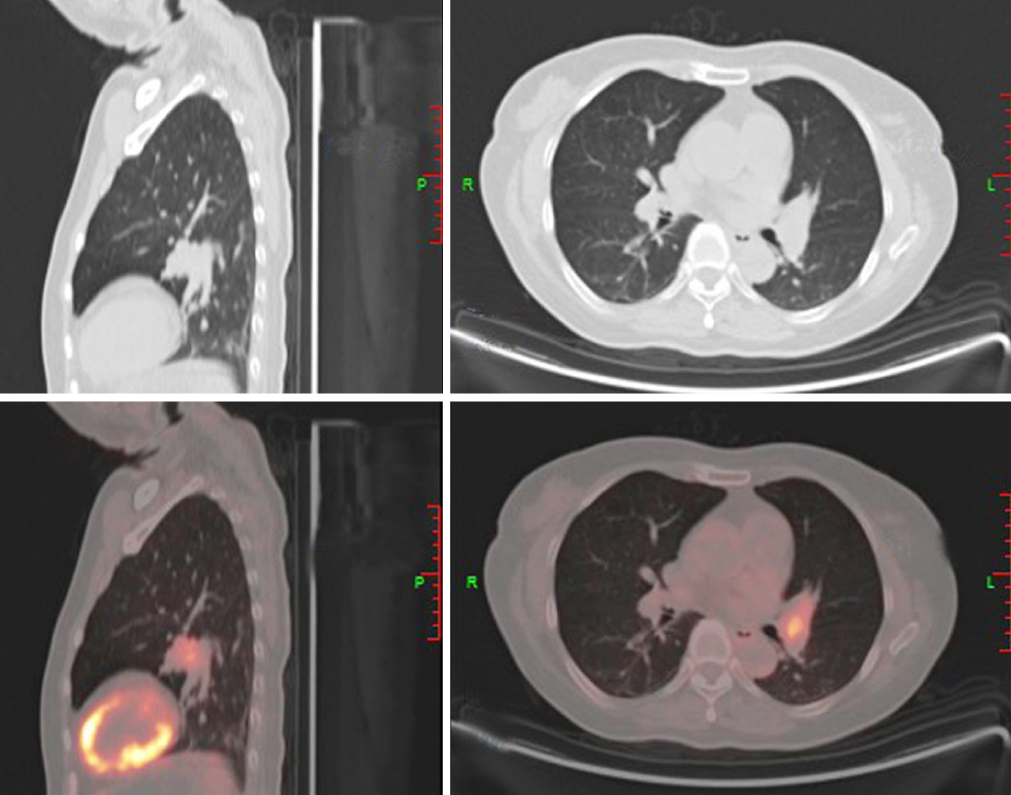

Imaging examination: Pituitary punctate enhanced imaging showed nothing abnormal. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography-CT showed a hypermetabolic nodule in the left lingular lobe. An immunohistochemistry test for antibodies showed the presence of Ki-67, thyroid transcription factor-1, CD56, and Synaptophysin. These results are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

According to the typical symptoms, physical examination, and imaging findings, this patient was diagnosed with SCLC (cT2aN3M0) with EAS.

According to the typical symptoms, physical examination, and imaging findings, the patient was diagnosed with SCLC with EAS.

Antineoplastic treatment was prescribed, comprising six courses of chemotherapy (etoposide + cisplatin) and three courses of biotherapy. Radiotherapy was also admitted to the treatment plan (54 Gy/1.8 Gy/30 fractions).

Treatment comprised of diabetic diet, lowering blood glucose, and correcting electrolyte disturbances. Etoposide + cisplatin were given.

Thyroid function, cortisol and ACTH were all back to normal range after the second course of chemotherapy. Lung CT revealed that the lesion had reduced by one-third. However, bone metastasis (T2aN3M1b) was found in manubrium sterni and centrum T6 after the fourth course of chemotherapy. Re-examination showed enlargement of the pulmonary lesion. Abdominal CT showed liver metastases. Severe hypokalemia (lowest: 1.85 mmol/L) and hypertension reoccurred, and bone marrow metastasis was found.

The thyroid function, cortisol, ACTH, fasting and postprandial glucose, and hemoglobin A1c were back to normal ranges after 3 mo.

Both patients reported here were admitted with diabetes mellitus. They had the following common features: (1) middle age, smoking history and hypokalemia; (2) no significant clinical manifestations of Cushing’s syndrome, but increased ACTH and high level of cortisol in serum and urine; and (3) bronchoscopic biopsy confirmed SCLC. Changes in thyroid function in both patients were attributed to inhibition of the pituitary–thyroid axis by excess cortisol[16]. The condition of Patient 1 deteriorated rapidly, losing the best opportunity for treatment, whereas Patient 2 remained healthy for 2 years.

EAS is usually caused by neuroendocrinological carcinoma, mainly SCLC (45%), thymic carcinoma (15%), bronchus carcinoid (10%), pancreas islet-cell carcinoma (10%), chromaffin tumor (2%), and oophoroma (1%), as well as some other rare causes[17-19]. Cushing’s syndrome caused by SCLC with ectopic ACTH production is reported to occur in 1.6%–4.5% of patients with SCLC[11]. Qualitative diagnosis of EAS is based on clinical manifestations and hormonal tests[20]. Localization of EAS is based on CT, magnetic resonance imaging and octreotide scan, which is effective in detecting minor lesions[21]. Measurement of ACTH and cortisol concentrations and performance of a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test are useful methods for diagnosis of EAS. CT, positron emission tomography-CT and bronchoscopic biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of SCLC. The median survival time of patients with SCLC with EAS is short[22]. For EAS, surgery remains the optimal treatment in all forms of Cushing’s syndrome[23]. Some reports showed that metyrapone, ketoconazole and octreotide are effective but not widely used due to the adverse effects and long onset of action[24-26].

Available evidence on the relationship between SCLC and diabetes is limited. Several studies have confirmed that 8%–18% of cancer patients have diabetes mellitus, and type 2 diabetes mellitus is believed to be a risk factor for several solid tumors[27-30]. Furthermore, clinical studies have indicated that patients with both cancer and diabetes usually have a poor prognosis[31,32]. Xu et al[33] reported that treatment of diabetes using metformin can improve prognosis of SCLC based on their results including 79 SCLC patients with diabetes. Thus, diabetes might play an important role in the development and prognosis of cancer[34,35]. Early diagnosis of diabetes might be indicative of the later detection of several cancers such as LC. Unfortunately, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. We think that hypercortisolism induced by EAS might paly a key role in the dysfunction of glucose homeostasis, which provokes hyperglycemia. Thus, high blood glucose level is not simply a reflection of diabetes, but might also be a manifestation of serious disorders that require clinicians to take notice.

The conclusion of the current findings is that SCLC might start with diabetes mellitus. High blood glucose level is not simply a reflection of diabetes, and might be a manifestation of serious disorders that requires attention from clinicians. Increased cortisol and hypokalemia were the most significant factors in our patients’ conditions, which should be monitored carefully during treatment. Furthermore, early and accurate diagnosis of SCLC patients with diabetes is essential for prognosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Haneder S, Seo DW, Villanueva MT S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21371] [Article Influence: 2137.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Choi WI, Choi J, Kim MA, Lee G, Jeong J, Lee CW. Higher Age Puts Lung-Cancer Patients at Risk for Not Receiving Anti-cancer Treatment. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang Y, Zhou Y, Hu Z. The Functions of Circulating Tumor Cells in Early Diagnosis and Surveillance During Cancer Advancement. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cheng LL, Liu YY, Su ZQ, Liu J, Chen RC, Ran PX. Clinical characteristics of tobacco smoke-induced versus biomass fuel-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Transl Int Med. 2015;3:126-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Grigorescu AC. Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced cancer: A pilot study in Institute of Oncology Bucharest. J Transl Int Med. 2015;3:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, Read W, Tierney R, Vlahiotis A, Spitznagel EL, Piccirillo J. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4539-4544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1197] [Cited by in RCA: 1397] [Article Influence: 73.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES; Community of Population-Based Regional Cancer Registries. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2015. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50:303-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li X, Li B, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun X, Yu Y, Wang L, Yu J. Prognostic value of dynamic albumin-to-alkaline phosphatase ratio in limited stage small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Legius B, Nackaerts K. Severe intestinal ischemia during chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Manag. 2017;6:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Üstün F, Tokuc B, Tastekin E, Durmuş Altun G. Tumor characteristics of lung cancer in predicting axillary lymph node metastases. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2019;38:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aoki M, Fujisaka Y, Tokioka S, Hirai A, Henmi Y, Inoue Y, Narabayashi K, Yamano T, Tamura Y, Egashira Y, Higuchi K. Small-cell Lung Cancer in a Young Adult Nonsmoking Patient with Ectopic Adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) Production. Intern Med. 2016;55:1337-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lin CJ, Perng WC, Chen CW, Lin CK, Su WL, Chian CF. Small cell lung cancer presenting as ectopic ACTH syndrome with hypothyroidism and hypogonadism. Onkologie. 2009;32:427-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Delisle L, Boyer MJ, Warr D, Killinger D, Payne D, Yeoh JL, Feld R. Ectopic corticotropin syndrome and small-cell carcinoma of the lung. Clinical features, outcome, and complications. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:746-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dehghan M, Mente A, Zhang X, Swaminathan S, Li W, Mohan V, Iqbal R, Kumar R, Wentzel-Viljoen E, Rosengren A, Amma LI, Avezum A, Chifamba J, Diaz R, Khatib R, Lear S, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Liu X, Gupta R, Mohammadifard N, Gao N, Oguz A, Ramli AS, Seron P, Sun Y, Szuba A, Tsolekile L, Wielgosz A, Yusuf R, Hussein Yusufali A, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Bangdiwala SI, Islam S, Anand SS, Yusuf S; Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators. Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390:2050-2062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 737] [Article Influence: 92.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Magliano DJ, Bennett PH. Diabetes mellitus statistics on prevalence and mortality: facts and fallacies. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:616-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mazzoccoli G, Pazienza V, Piepoli A, Muscarella LA, Giuliani F, Sothern RB. Alteration of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis function in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:327-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wajchenberg BL, Mendonca BB, Liberman B, Pereira MA, Carneiro PC, Wakamatsu A, Kirschner MA. Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:752-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aniszewski JP, Young WF, Thompson GB, Grant CS, van Heerden JA. Cushing syndrome due to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion. World J Surg. 2001;25:934-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hayes AR, Grossman AB. The Ectopic Adrenocorticotropic Hormone Syndrome: Rarely Easy, Always Challenging. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018;47:409-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Howlett TA, Drury PL, Perry L, Doniach I, Rees LH, Besser GM. Diagnosis and management of ACTH-dependent Cushing's syndrome: comparison of the features in ectopic and pituitary ACTH production. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1986;24:699-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Santhanam P, Taieb D, Giovanella L, Treglia G. PET imaging in ectopic Cushing syndrome: a systematic review. Endocrine. 2015;50:297-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim EY, Kim N, Kim YS, Seo JY, Park I, Ahn HK, Jeong YM, Kim JH. Prognostic Significance of Modified Advanced Lung Cancer Inflammation Index (ALI) in Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer_ Comparison with Original ALI. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Paduraru DN, Nica A, Carsote M, Valea A. Adrenalectomy for Cushing's syndrome: do's and don'ts. J Med Life. 2016;9:334-341. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Ma L, Yin L, Hu Q. Therapeutic compounds for Cushing's syndrome: a patent review (2012-2016). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2016;26:1307-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Clark AJ, Forfar R, Hussain M, Jerman J, McIver E, Taylor D, Chan L. ACTH Antagonists. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016;7:101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alexandraki KI, Grossman AB. Therapeutic Strategies for the Treatment of Severe Cushing's Syndrome. Drugs. 2016;76:447-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Richardson LC, Pollack LA. Therapy insight: Influence of type 2 diabetes on the development, treatment and outcomes of cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:48-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wu L, Rabe KG, Petersen GM. Do variants associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer and type 2 diabetes reciprocally affect risk? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gong Y, Wei B, Yu L, Pan W. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of oral cancer and precancerous lesions: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:332-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yeo Y, Ma SH, Hwang Y, Horn-Ross PL, Hsing A, Lee KE, Park YJ, Park DJ, Yoo KY, Park SK. Diabetes mellitus and risk of thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sehgal V, Childress R. Urgent Need to Define Pretreatment Predictors of Immune Check Point Inhibitors Related Endocrinopathies: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:235-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | St Onge E, Miller S, Clements E, Celauro L, Barnes K. The Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:79-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Xu T, Liang G, Yang L, Zhang F. Prognosis of small cell lung cancer patients with diabetes treated with metformin. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:819-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hjartåker A, Langseth H, Weiderpass E. Obesity and diabetes epidemics: cancer repercussions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;630:72-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Luo J, Hendryx M, Qi L, Ho GY, Margolis KL. Pre-existing diabetes and lung cancer prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |