Published online May 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i10.1177

Peer-review started: December 29, 2019

First decision: March 10, 2019

Revised: March 29, 2019

Accepted: April 9, 2019

Article in press: April 9, 2019

Published online: May 26, 2019

Processing time: 148 Days and 20.4 Hours

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for 15% of lung cancers, and it commonly expresses peptide and protein factors that are active as hormones. These secreting factors manifest as paraneoplastic disorders, such as ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) syndrome (EAS). The clinical features are abnormalities in carbohydrate metabolism, hypokalemia, peripheral edema, proximal myopathy, hypertension, hyperpigmentation, and severe systemic infection. However, it is uncommon that EAS has an influence on hypothalamus-pituitary function.

A 62-year-old man presented with complaints of haemoptysis, polyuria, polydipsia, increased appetite, weight loss, and pigmentation. Following a series of laboratory and imaging examinations, he was diagnosed with SCLC, EAS, hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, and central diabetes insipidus. After three rounds of chemotherapy, levels of ACTH, cortisol, thyroid hormone, gonadal hormone, and urine volume had returned to normal levels. In addition, the pulmonary tumor was reduced in size.

We report a rare case of SCLC complicated with panhypopituitarism due to EAS. We hypothesize that EAS induced high levels of serum glucocorticoid and negative feedback for the synthesis and secretion of antidiuretic hormone from the paraventricular nucleus, and trophic hormones from the anterior pituitary. Therefore, patients who present with symptoms of hypopituitarism, or even panhypopituitarism, with SCLC should be evaluated for EAS.

Core tip: Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome (EAS) is the common paraneoplastic disorder in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). However, it is uncommon that EAS has an influence on hypothalamus-pituitary function. Here, we report a rare case of SCLC complicated with panhypopituitarism due to EAS. We hypothesize that EAS induced high levels of serum glucocorticoid and negative feedback for the synthesis and secretion of antidiuretic hormone from the paraventricular nucleus, and trophic hormones from the anterior pituitary.

- Citation: Jin T, Wu F, Sun SY, Zheng FP, Zhou JQ, Zhu YP, Wang Z. Small cell lung cancer with panhypopituitarism due to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(10): 1177-1183

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i10/1177.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i10.1177

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC), which derived from neuroendocrine tissue, can appear the paraneoplastic disorders, such as ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) syndrome (EAS). With regards to the clinical features of EAS, the degree of gluco-corticoid level seems to be the major determinant. We report a case of SCLC with panhypopituitarism due to EAS presenting with hypogonadotropic, hypogonadism, secondary hypothyroidism, and central diabetes insipidus.

A 62-year-old male patient admitted to endocrinology clinic with polyuria, poly-dipsia, increased appetite, weight loss, pigmentation, haemoptysis, and fatigue that developed over two months. This was his first coming to the hospital.

The patient had underwent phacoemulsification ten years ago.

The patient reported a history of smoking (40 packs/year), and denied drug use. His father died of the unknown cause and his mother died of a heart attack. His brother had diabetes mellitus.

The blood pressure was 151/99 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa), and body mass index was 21.09 kg/m2. Pigmentation was observed on his face, his lip and buccal mucosa. Respiratory sounds in the bilateral lungs were rough, although no rales were heard.

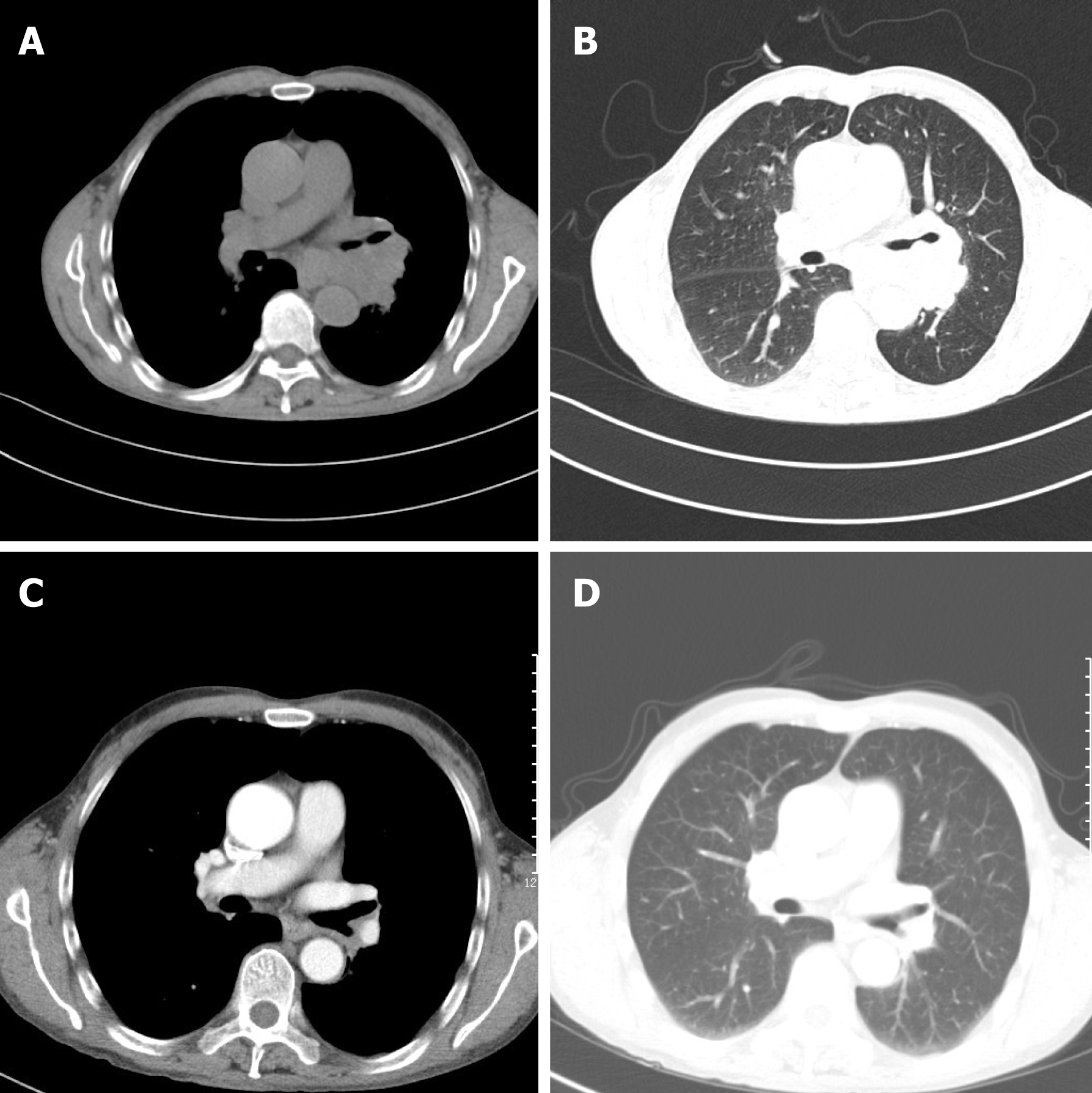

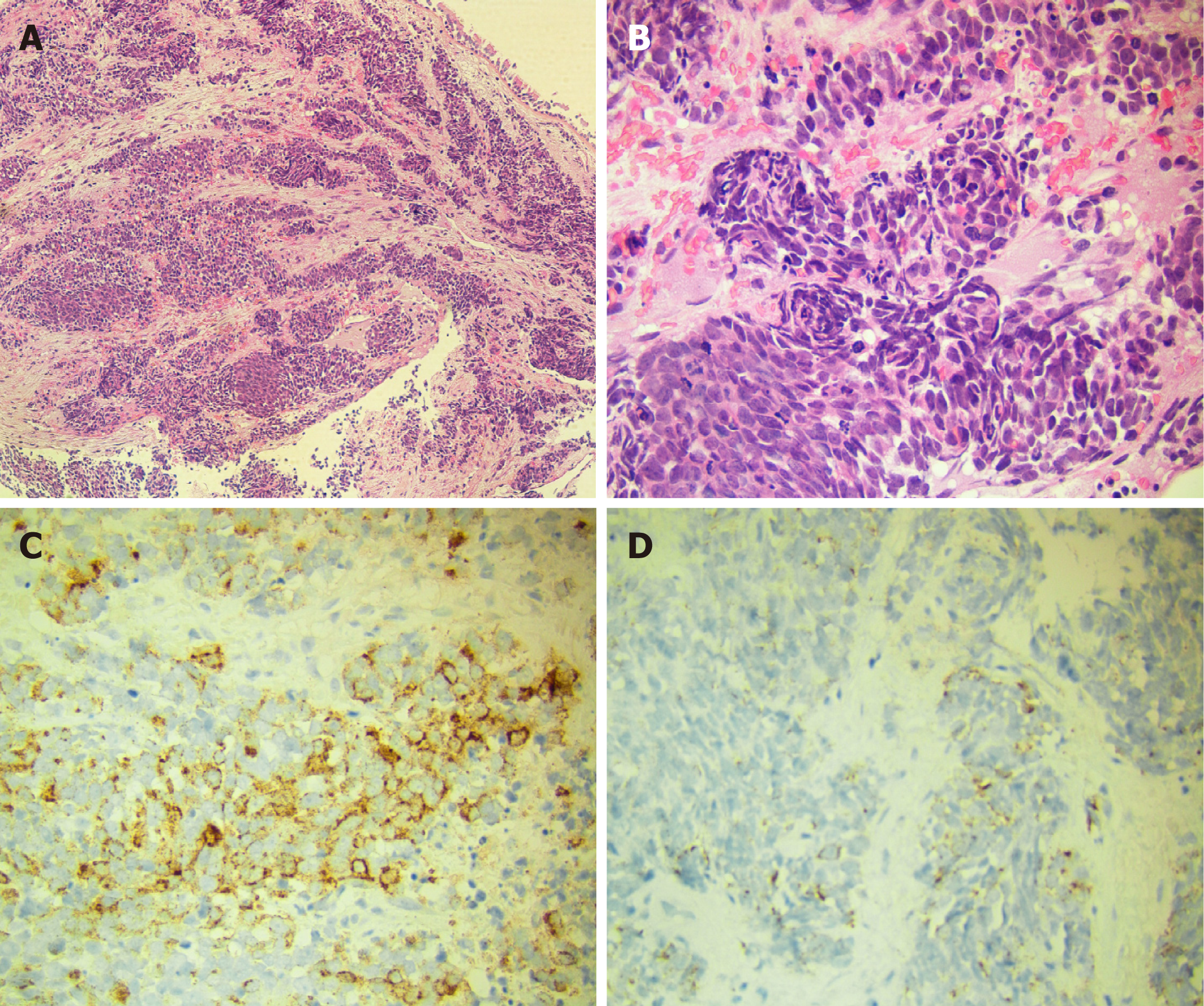

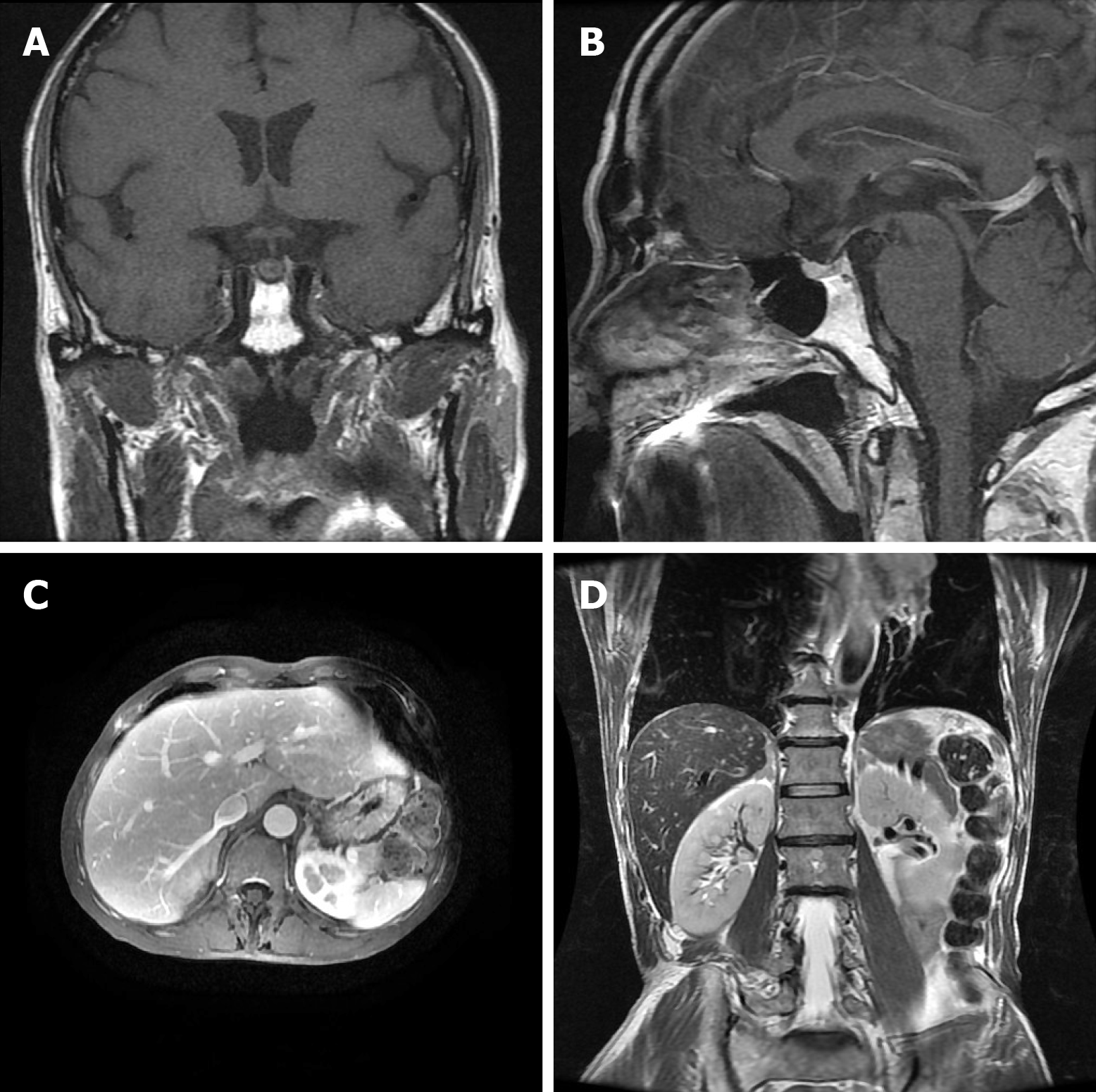

Laboratory data also revealed an increase in levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (12.37 ng/mL), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (12.76 mmol/L), HbA1c (8.9%), and urine sugar (3+). An oral glucose tolerance test indicated diabetes mellitus. Levels of blood ACTH, blood cortisol, and 24 h urine cortisol were elevated, and cortisol secretion was found to be disordered (Table 1). Low-dose and high-dose dexamethasone suppression tests both were not suppressed (8 am cortisol before test was 31.17 μg/dL, after low-dose dexamethasone suppression test was 37.04 μg/dL, after high-dose dexamethasone suppression test was 53.5 μg/dL). Levels of testosterone, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), total thyroxine (TT4), total tri-iodothyronine (TT3), and free tri-iodothyronine (FT3) were all reduced, although levels of blood luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, prolactin, growth hormone (GH), free thyroxine (FT4) were all normal (Table 1). The patient’s 24 h urine potassium level was 105.5 mmol, while the synchronous serum potassium level was 2.96 mmol/L. Water deprivation and vasopressin tests indicate partial central diabetes insipidus (Table 2). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed a hilar mass and chronic obstructive inflammation in the left lower lung (Figure 1A and B). A fiber optic bronchoscopy revealed a neoplasm present on the lower segment of the left main bronchus. A brush cell pathological examination showed a very small amount of heterocyst, and a histopathological examination detected expression of Leukocyte differentiation antigen (CD56), synaptophysin (Syn), chromogranin A (CgA), and cytokeratin (CK). Assays of NSE and ACTH were found to be positive. Thus, SCLC of the left lower bronchus was diagnosed (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary showed normal and MRI of the adrenal glands revealed bilateral adrenal hyperplasia (Figure 3). An emission computed tomography of the patient’s bones revealed radioactivity concentrated in the sixth and seventh right anterior ribs, and a punctiform concentration of radioactivity was observed on the right oxter. In combination, the results of these examinations suggest that the neoplasm staging is IIIA (T3N1M0).

| Biochemical assay | Normal range | Prior to chemotherapy | After 1stround | After 2ndround | After 3rdround |

| 8 am ACTH | 10–80 ng/L | 210 | 127 | 74 | 45 |

| 4 pm ACTH | 5–40 ng/L | 192 | 100 | 43 | 21 |

| 8 am cortisol | 8.7–22.4 μg/dL | 31.17 | 16.79 | 8.8 | 8.64 |

| 4 pm cortisol | 0–10 μg/dL | 35.18 | 11.26 | 2.36 | 2.47 |

| 0 am cortisol | 0–5 μg/dL | 31.27 | 14.47 | 1.75 | 3.64 |

| 24 h urine cortisol | > 1932.8 | 341.6 | 154.4 | 120.5 | |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.6 | 4 | 5.8 | 5.4 | |

| 2 h PPG (mmol/L) | 13 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 6.8 | |

| Testosterone | 1.75–7.81 μg/L | 0.98 | 0.94 | 3.57 | 4.01 |

| FSH | 1.27–19.26 IU/L | 5.58 | 5.09 | 12.79 | 16.68 |

| LH | 1.24–8.62 IU/L | 4.18 | 2.02 | 6.08 | 5.42 |

| TSH | 0.35–4.94 mIU/L | 0.07 | 1.36 | 1.46 | 0.94 |

| TT4 | 4.87–11.72 μg/dL | 4.19 | 4.41 | 7.83 | 6.15 |

| TT3 | 0.58–1.59 ng/mL | 0.43 | 0.56 | 1.31 | 1.19 |

| FT4 | 0.7–1.48 ng/dL | 0.94 | 0.83 | 1.17 | 0.84 |

| FT3 | 1.71–3.71 pg/mL | 1.4 | 1.63 | 3.7 | 2.82 |

| 24 h urine volume (mL/d) | 3200 | 2800 | 2400 | 1170 | |

| Urine specific gravity | 1.015–1.025 | 1.010 | 1.014 | 1.016 | 1.020 |

| NSE | 0–15.2 ng/mL | 18.27 | 9.59 | 10.39 | - |

| CEA | 0–5 ng/mL | 7.35 | 2.91 | 2.69 | - |

| Time | Urine volume (mL) | Urine specific gravity | Plasma osmotic pressure (osmo/kg) | Weight (kg) | Blood pressure (mmHg) | Heart rate (bpm) | Notes |

| 1st day 22:00 | 250 | 1.010 | 298 | 51.0 | 136/75 | 73 | Start water deprivation |

| 2nd day 11:50 | 100 | 1.012 | 305 | 48.5 | 131/77 | 81 | Platform stage pituitrin administration |

| 2nd day 12:50 | 100 | 1.018 | - | 49.0 | 103/74 | 75 | - |

| 2nd day 13:50 | 50 | 1.018 | 301 | 49.0 | 121/76 | 76 | Off-test |

According to the above results, SCLC (T3N1M0), EAS, hypothyroidism, hypogo-nadism, diabetes insipidus, and dubious special type diabetes mellitus were diagnosed.

An EP regimen of chemotherapy, including etoposide (170 mg administration d 1-3) and cis-platinum (100 mg administration d 1) were administered once every 21 d, with four rounds completed to date. In addition, insulin aspart and glargine were used to control the patient’s blood glucose level. However, no medicine was admi-nistered to treat EAS, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism and diabetes insipidus (Table 1).

After the second round of chemotherapy, the patient’s tumor markers, blood ACTH, blood cortisol, 24 h urine cortisol, gonadal hormone, gonadotrophins, TH, TSH, 24 h urine volume, and urine specific gravity returned to normal levels. In addition, the insulin dose administered was gradually decreased. Currently, the patient receives Glucobay (50 mg tid) only, and his FPG and postprandial plasma glucose are both well controlled (Table 1). A chest CT scan after the third round of chemotherapy also indicated that the volume of the hilar mass was reduced (Figure 1C and D). However, the follow-up survey of the patient was terminated because of the contact information change of the patient.

EAS is typically more common in males than females (3:1), and often occurs between the ages of 40 and 60 years[1]. Previously, SCLC has accounted for most cases of EAS[2]. However, in recent surveys, cases of EAS have been found to involve bronchial carcinoid tumours (> 25%), SCLC (approximately 20%), adenocarcinomas (about 20%), tumors of the thymus (11%), and pancreatic tumors (8%). In addition, medullary thyroid carcinoma, mediastinal tumors, gastrointestinal tumors, and genital tract tumors have been found to cause EAS[3]. Patients with EAS may develop hypokalemia accompanied by alkalosis, myasthenia, edema, pigmentation, crinosity, hypertention, and hyperglycemia. Moreover, Isidori et al[4] reported that EAS patients with SCLC more commonly presented with skin pigmentation, while symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome were absent. These characteristics may be due to the rapidity of tumor development and the severity of hypercortisolaemia induced by SCLC[4].

In the present case, a 62-year-old male patient was diagnosed with SCLC, EAS, hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, and central diabetes insipidus. It is unusual that EAS would have an influence on hypothalamus-pituitary function and affect functions of the thyroid, gonad, or other target glands. In recent years, however, several cases of SCLC complicated with EAS, hypothyroidism, and hypogonadism have been reported worldwide[5]. Previous studies have demonstrated that serum TSH levels often decrease as a result of glucocorticoid effects at both the hypothalamic and pituitary levels[6], while serum T3 levels can decrease due to an inhibition of peripheral conversion of T4 by glucocorticosteroids[7]. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism have also been reported, which are hypothesized to be the result of glucocorticoid sup-pression at the hypothalamo-pituitary level[8]. Since the patient’s pituitary-gonad and pituitary-thyroid axes were both suppressed by hypercortisolism, these results suggest that the level of GH might also be suppressed. In this study, the patient’s level of GH was within the lower limit of the normal range. However, the patient refused an insulin tolerance test, which is considered the gold standard for diagnosing GH deficiency.

In addition, the patient also developed apparent polyuria and polydipsia. A urine test revealed a lower specific gravity, water deprivation and vasopressin tests indicate partial central diabetes insipidus. Previously, cases of EAS complicated with central diabetes insipidus have been reported, most of which involved posterior pituitary metastasis[9]. Since the patient in the present case had a urine volume of 3-4 L/d, water deprivation and vasopressin tests (Table 2) showed incomplete diabetes insipidus, and a pituitary MRI revealed normal (Figure 3A and B), the possibility of early pituitary metastasis could not be completely excluded. Moreover, there may be other mechanism responsible for the development of diabetes insipidus. Glucocorticoid has also been associated with mediating a negative feedback loop that affects secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the paraventricular nucleus[10]. Therefore, high serum levels of glucocorticoid associated with ectopic ACTH syndrome could result in central diabetes insipidus.

According to the pathology and staging of the tumor determined, EP chemo-therapy was administered. Following treatment, the hilar mass was reduced in size and levels of tumor markers returned to a normal range. Furthermore, the blood ACTH, blood cortisol, 24 h urine cortisol, blood pressure, gonadal hormone, and TH all gradually returned to normal ranges without any treatment. Blood glucose levels were also well-controlled and insulin dosages were decreased day by day. The patient’s 24 h urine volume was reduced, and the urine specific gravity increased too. Based on these outcomes, the diagnosis that hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, and diabetes insipidus experienced by the patient were related to EAS was confirmed.

This case of SCLC complicated with EAS, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, se-condary hypothyroidism, and central diabetes insipidus is unique, and to our knowledge, is the first of its type to be reported. EP chemotherapy was found to treat the SCLC, and also served to correct the clinical disorders caused by EAS. We hypothesize that negative feedback by high levels of serum glucocorticoid affected the synthesis and secretion of ADH from the paraventricular nucleus and trophic hormones from the anterior pituitary to contribute to the patient’s condition. It is also possible that inadequate secretion of ADH due to tumor metastasis to the posterior pituitary may have been involved. Further studies will be needed to distinguish these possibilities.

We wish to thank Dr. Beibei Zhang, who ever was one of our colleagues, for kindly helping in the writing in this manuscript. And we wish to thank Hong Li, now the department director, for support in the clinical management.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Neninger E, Su CC S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Yang YN. Disease of endocrinology system: heterologous endocrine syndrome: ectopic ACTH syndrome. In: Haozhu Chen (ed). Practice of Internal Medicine (12th). People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing 2005; 1300-1301 (In Chinese). |

| 2. | Beuschlein F, Hammer GD. Ectopic pro-opiomelanocortin syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2002;31:191-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Isidori AM, Lenzi A. Ectopic ACTH syndrome. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51:1217-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Isidori AM, Kaltsas GA, Pozza C, Frajese V, Newell-Price J, Reznek RH, Jenkins PJ, Monson JP, Grossman AB, Besser GM. The ectopic adrenocorticotropin syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, management, and long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lin CJ, Perng WC, Chen CW, Lin CK, Su WL, Chian CF. Small cell lung cancer presenting as ectopic ACTH syndrome with hypothyroidism and hypogonadism. Onkologie. 2009;32:427-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kakucska I, Qi Y, Lechan RM. Changes in adrenal status affect hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone gene expression in parallel with corticotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2795-2802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Duick DS, Warren DW, Nicoloff JT, Otis CL, Croxson MS. Effect of single dose dexamethasone on the concentration of serum triiodothyronine in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1974;39:1151-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marazuela M, Cuerda C, Lucas T, Vicente A, Blanco C, Estrada J. Anterior pituitary function after adrenalectomy in patients with Cushing's syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69:547-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tanaka H, Kobayashi A, Bando M, Hosono T, Tsujita A, Yamasawa H, Ohno S, Hironaka M, Sugiyama Y. [Case of small cell lung cancer complicated with diabetes insipidus and Cushing syndrome due to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;45:793-798. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Huang CH, Chou KJ, Lee PT, Chen CL, Chung HM, Fang HC. A case of lymphocytic hypophysitis with masked diabetes insipidus unveiled by glucocorticoid replacement. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:197-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |