Published online Sep 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i10.322

Peer-review started: April 21, 2018

First decision: June 15, 2018

Revised: June 28, 2018

Accepted: July 23, 2018

Article in press: July 24, 2018

Published online: September 26, 2018

Processing time: 158 Days and 5.2 Hours

Labial and oral melanotic macules are commonly encountered in a broad range of conditions ranging from physiologic pigmentation to a sign of an underlying life-threatening disease. Although Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) shares some features of labial and oral pigmentation with a variety of conditions, it is a benign and acquired condition, frequently associated with longitudinal melanonychia. Herein, the demographic, clinical, dermoscopic, and pathological aspects of LHS were reviewed comprehensively. The important differential diagnoses of mucocutaneous and nail pigmentation are provided. An accurate diagnosis is crucial to design a reasonable medical strategy, including management options, malignant transformation surveillance, and psychological support. It is important that clinicians conduct long-term follow-up and surveillance due to the potential risks of malignant transformation and local severe complications in some conditions.

Core tip: Although Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) is an uncommon disorder, labial or oral pigmentation is often encountered daily and clinically. By conducting a thorough review of the topic, the aims of the paper are to present the clinical, dermoscopic, and pathological features of LHS concisely and clearly. More to the point, the outlined typical features of various conditions associated with labial, oral, and nail pigmentation are conducive to facilitate differential diagnosis, promote early recognition of underlying diseases, and prevent unnecessary testing.

- Citation: Duan N, Zhang YH, Wang WM, Wang X. Mystery behind labial and oral melanotic macules: Clinical, dermoscopic and pathological aspects of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(10): 322-334

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i10/322.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i10.322

In 1970, Laugier and Hunziker reported five cases of unusual acquired macular hyperpigmentation on the lips and oral mucosa, and two of these patients displayed longitudinal pigmented streaks on the nails[1]. Based on the names of the original reporters, Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) was used to represent the clinical entity subsequently. Since the original description, approximately 200 cases of LHS have been reported in the literature.

To date, the exact etiology of LHS remains unknown. Regarding the syndrome, evidence of underlying disorders or systemic abnormalities and increased malignancy risk has not been established. LHS occurs predominantly among middle-aged adults and affects women more frequently[2-6]. Clinically, the mucocutaneous pigmentary lesions in LHS characteristically present with lenticular melanotic macules on labial, oral, and acral areas. Longitudinal melanonychia is identified in approximately half of LHS patients. Dermoscopic findings of LHS mainly include regular reticular, granular, linear, curvilinear, arc streaks, fish scale-like, parallel furrow, or parallel ridge patterns in mucocutaneous pigmentary lesions[7-10]. Pathologically, melanin accumulates in the basal layer of the epithelium or epidermis and the number of melanophages in the lamina propria or dermis increases. However, the number of melanocytes is unaffected[4,11-13].

Labial and oral pigmentation is encountered in a broad range of conditions. Although the pigmentary lesions might appear trivial and insignificant, proper identification of characteristic pigmentation and subsequent establishment of differential diagnoses can promote essential examination and evaluation, facilitate an early diagnosis of potential underlying diseases, guide a reasonable medical strategy, prevent unnecessary testing, and reduce mortality due to malignancies and severe complications.

An extensive search of published case reports and review literatures on LHS since 1970 was performed based on the key words “Laugier–Hunziker syndrome,” “Laugier-Hunziker-Baran syndrome,” “essential lenticular melanotic pigmentation,” “idiopathic lenticular mucocutaneous pigmentation,” “Laugier and Hunziker pigmentation,” “Laugier’s disease,” or “longitudinal melanonychia.” Most of the studies that were assessed and studied were in English. A certain number of LHS cases from Europe have been reported in early articles in different languages. Therefore, these studies were also reviewed.

Through the literature review, demographic data were extracted and analyzed. In the intervening 48 years, only 206 cases of LHS were reported in 87 studies, and the majority was from Europe[1,3-88]. Among them, 187 cases were reported with sufficient age data, and 197 cases were reported with complete gender information. According to the literature review results, the average age of the reported cases at diagnosis is 47.5 years old (range 12-87 years). Women are affected more frequently than men, with an overall female-to-male ratio of 1.8:1 (127 females, 70 males). LHS cases with various nationalities have been reported in the literature (Table 1).

| Country | No. of cases | Percentage (%) | Ref. | |

| 1 | France | 59 | 29 | [1,14,20-22,24,26,27,30,31] |

| 2 | Italy | 33 | 16 | [11,12,18,25,28,29,33,34-37,40,63] |

| 3 | China | 30 | 14.5 | [5,9,10,19,23,58,72] |

| 4 | United States | 14 | 7 | [13,16,32,42,46,51,60,67-69,73,77,85,88] |

| 5 | United Kingdom | 13 | 6 | [3,39,45,49,52,54,76] |

| 6 | Germany | 12 | 6 | [40,61] |

| 7 | India | 8 | 4 | [47,56,57,70,71,81,86] |

| 8 | Turkey | 6 | 3 | [7,50,53,62,75,83] |

| 9 | Greece | 5 | 2 | [6,40,48] |

| 10 | Japan | 5 | 2 | [8,44,55,59] |

| 11 | Lebanon | 3 | 1.5 | [17] |

| 12 | Portugal | 2 | 1 | [23,43] |

| 13 | Brazil | 2 | 1 | [65,78] |

| 14 | Spain | 2 | 1 | [66] |

| 15 | Australia | 2 | 1 | [87] |

| 16 | Finland | 1 | 0.5 | [4] |

| 17 | Ireland | 1 | 0.5 | [15] |

| 18 | Russia | 1 | 0.5 | [38] |

| 19 | Switzerland | 1 | 0.5 | [41] |

| 20 | South Korea | 1 | 0.5 | [64] |

| 21 | Austria | 1 | 0.5 | [74] |

| 22 | Serbia | 1 | 0.5 | [79] |

| 23 | Chile | 1 | 0.5 | [80] |

| 24 | Romania | 1 | 0.5 | [82] |

| 25 | Singapore | 1 | 0.5 | [84] |

LHS is typically acquired in adulthood and cases tend to be sporadic in nature[4,5,14,15]. A female preponderance with an overall female to male ratio of 2:1 has been proposed in the previous studies[3,16]. To date, evidence supporting a malignant tendency associated with LHS is lacking. In addition, no systemic abnormality or familial factor is associated with the syndrome. To date, only one report described a woman and her daughters affected with the condition[17]. Environmental risk factors have not been identified. Generally, pigmentary changes of individuals with LHS do not disappear naturally but slowly increase with age. To date, complete remission of pigmentation was reported in only one case[18].

The most common lesion sites are the lips, especially the lower lip, and the oral cavity, particularly the buccal mucosa. Frequently, pigmentation is also found on the tongue, gingiva, and palatal mucosa. However, the mouth floor is an extremely rare site[19]. Increased pigmentation occurs in the acral area and the genital region[7,12,20-23]. The finger pulp or tip and the periungual area are frequently affected with pigmentary macules. The palmoplantar area is less frequently affected. The location distribution of pigmentary lesions in LHS is provided in Table 2.

| Involved locations | Frequency | Ref. | |

| Lip | 75% (154/206) | [1,3-16,18,19,21-25,27-29,31-38,40,41,43-52,54-68,70-73,75-78,80,83,85-88] | |

| Oral cavity | 68% (140/206) | [1,3-9,11-19,21-24,26,27,29,31-33,35-44,46,47,50-60,62-76,78,79,81,82,84-88] | |

| Acral area | Nail | 47% (96/206) | [1,3-10,12,14-17,19,22,23,25-27,31,32,34,39-41,43,44,47,49,50,52-54,56-59,61,63-66,68-72,77-84,86] |

| Periungual area | 8% (17/206) | [8,14,16,25,31,34,43,47,50,54,64,65,71,73,77,79,81] | |

| Finger | 13% (26/206) | [5,8,9,11,14,19,21,41,43,49,55-57,59,60,66,70-72,74,76,84-86,88] | |

| Palm | 4% (8/206) | [7,43,44,46,59,60,62,81] | |

| Toes | 3% (6/206) | [19,56,59,70,84,86] | |

| Sole | 3% (6/206) | [7,21,46,59,62] | |

| Genitalia | Penis | 24% (17/70)1 | [20-23,46] |

| Vulva or labia majora | 10% (13/127)1 | [7,12,15,17,21,30,58,74] | |

| Anal mucosa and perianal area | 1.5% (3/206) | [21,41] | |

| Conjunctiva and sclera | 4% (9/206) | [6,7,17,19,23,46,60,83] | |

| Eyebrow and periorbital area | 1.5% (3/206) | [41,53,71] | |

| Pharynx | 0.5% (1/206) | [4] | |

| Esophagus | 0.5% (1/206) | [44] | |

| Neck, thorax, and abdomen | 1% (2/206) | [25,81] | |

| Back | 0.5% (1/206) | [50] | |

| Elbow | 1% (2/206) | [43,76] | |

| Pretibial area | 0.5% (1/206) | [62] | |

Typically, the cutaneous or mucosal lesions manifest as gray, brown, blue-black, or black macules with a flat, smooth surface and relatively well-defined or indistinct margin. The lesions are generally 2 to 5 mm in diameter and lenticular, oval, or irregular in shape. Hyperpigmented macules are distributed in variable numbers. Single or multiple lesions are observed, and occasionally, the lesions are confluent[11,12,19,21,41,42,44]. Symptoms are generally absent. Figure 1 presents typical lenticular melanotic macules on the lower lip of a patient affected with LHS.

Labial or oral hyperpigmentation may be accompanied by nail pigmentation. Longitudinal melanonychia is observed in approximately 44%-60% of LHS patients[3,15,27,39,46,59]. The typical nail pigmentation in LHS manifests as single or double longitudinal brownish-black streaks with a homogeneous, smooth, and flat appearance. According to the classification by Baran[27], the nail pigmentation in LHS is mainly categorized into three types: A single 1 to 2 mm wide longitudinal streak, a double 2 to 3 mm wide longitudinal streak on the lateral portion of the nail plate, and homogeneous pigmentation of the radial or ulnar half of the nail plate. Veraldi et al[11] reported a fourth type, namely, complete pigmentation of the nail plate. All four types of nail involvement may simultaneously affect one or more fingernails and/or toenails. However, the degree of the pigmentation does not correspond to different stages of the syndrome. Fingernails are more frequently involved compared to the toenails[11]. Pseudo-Hutchinson’s sign, which refers to nail matrix pigmentation that is visible through a translucent cuticle on periungual tissues and more frequently on the hyponychium, is commonly observed.

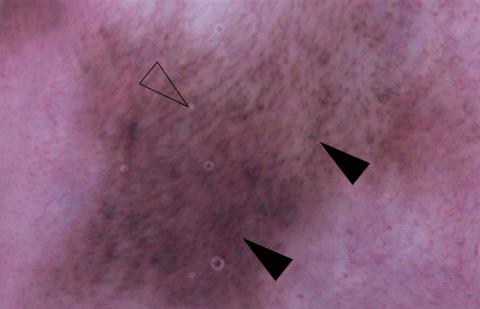

As a useful and noninvasive auxiliary diagnostic method, dermoscopy has been used for a more accurate diagnosis of pigmented lesions, including in LHS lesions. The dermoscopic findings of labial lesions in LHS consist of parallel furrow pattern with multiple brown dots[7]; multiple brown or blue-gray granular patterns[8]; a regular brownish reticular pattern including arc streaks, granules, and networks[10]; a regular brown network pattern with a homogenous blue area[61]; brown reticular lines, globules, parallel lines[83]; and a fish scale-like pattern[88]. These dermoscopic patterns are frequently noted along with linear and dotted vessels on whitish pink areas[10,61]. Figure 2 presents the dermoscopic findings of the aforementioned LHS patient.

Similarly, the dermoscopic findings of mucosal pigmentary lesions in LHS are composed of a regular brownish reticulate pattern with linear or curvilinear vasculature on the buccal mucosa[9], a parallel furrow pattern with linear and curvilinear streaks on the vulva[7] and a light brown colored homogeneous pattern on the conjunctiva[88]. Furthermore, the dermoscopic findings of cutaneous pigmentary lesions in LHS consist of a parallel furrow pattern in the palmoplantar region[7]; a parallel ridge pattern on the finger pulp[8,9,66], fingertip and palm[66]; a brown to grayish homogeneous pattern[88]; and a fibrillar pattern in the periungual area[8].

Additionally, the dermoscopic findings of ungual pigmentary lesions in LHS mainly include homogenous, regular, brownish or grayish, bandlike[7,9,66,82] and linear[8,9,82,83] patterns with ill-defined margins on the nail plate. Sometimes, dermoscopic examination of the nail unit can reveal micro-Hutchinson sign, which is almost invisible to the naked eye[82].

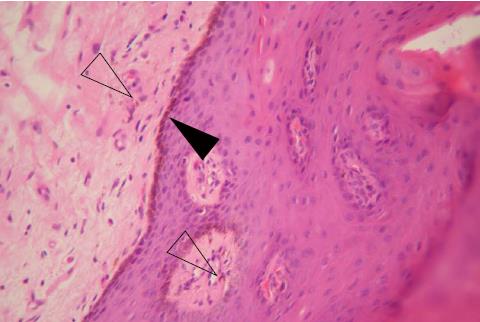

Typically, the pathological findings of pigmented lesions in LHS involve an accumulation of melanin in the cells of the basal layer of the epithelium or epidermis. Melanocytes are normal in number, morphologic appearance, and distribution. An increased number of melanophages, i.e., pigmentary incontinence, may be observed in the upper lamina propria or superficial connective tissues. Nevus cells are never observed. These features demonstrate that the condition is due to increased melanocytic activity rather than to an increased number of melanocytes[12]. Figure 3 presents the pathological findings of the aforementioned LHS patient.

The accumulation of melanin in basal layer cells is confined to the tips of epithelial rete ridges, which has been reported and observed through a review of the histopathologic findings in some reported cases[5,6,11,15,19,40,62,67,85]. Thus, this phenomenon is unclear and needs further investigation. In several cases, increased numbers of nonnested melanocytes were observed in the epithelial basal layer[32,51,53,81]. An atypical report described slight cellular atypia of intraepidermal melanocytes in a sun-exposed skin lesion[51]. Acanthosis[6,13,17,22,42,44,70,81,86,88], hyperkeratosis[60,70,81,86], hyperparakeratosis[6,88], or spongiosis[13,53] of the epithelium and elongated rete ridges[6,32,81,88] have been noted in some reported cases.

A broad differential diagnosis should be considered when evaluating labial, oral, and cutaneous hyperpigmentation (Table 3). Generally, a diagnosis of exclusion should be taken into consideration. Labial and oral pigmentation is either focal or diffuse. Although focal lesions may be more worrying and require a biopsy for an accurate diagnosis, diffuse lesions usually have no specific histological features and may be the first sign of an underlying systemic disease[4].

| Focal | Diffuse | |

| Exogenous origin | Amalgam tattoo | Tobacco-associated melanin pigmentation |

| (smoker’s melanosis) | ||

| Topical medications | Drugs (e.g., antimalarials, tetracyclines, ketoconazole, zidovudine, phenothiazines, oral contraceptives, and chemotherapeutic agents) | |

| Graphite tattoo (e.g., carbon, lead pencils) | Heavy metals (including bismuth, mercury, silver, lead, gold, arsenic, tin, copper, brass, zinc, cadmium, chrome, and manganese) | |

| Endogenous origin | Melanotic macule | Physiologic (racial) pigmentation |

| Melanocytic nevus | Posttraumatic or postinflammatory pigmentation | |

| Melanoacanthoma | Lichen planus | |

| Melanoma | Discoid lupus erythematosus | |

| Hemangioma | LHS | |

| Lentigo maligna | Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | |

| Kaposi sarcoma | Addison’s disease | |

| McCune-Albright syndrome | ||

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen’s disease) | ||

| Carney complex (NAME/LAMB syndrome) | ||

| LEOPARD syndrome (lentiginosis profusa syndrome) | ||

| Cronkhite-Canada syndrome | ||

| Cushing syndrome | ||

| Incontinentia pigmenti syndrome (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome) | ||

| Acanthosis nigricans | ||

| Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria | ||

| Tuberous sclerosis | ||

| Xeroderma pigmentosum | ||

| Dyskeratosis congenita | ||

| Hemochromatosis | ||

| Fanconi anemia |

Amalgam tattoo: Accidental displacement of metal particles into oral soft tissues during restorative procedures using the dental material amalgam may result in amalgam pigmentation, the so-called “amalgam tattoo”[89,90]. Amalgam tattoos are generally painless, solitary or multiple macules that range from a few millimeters to greater than one centimeter in size. The most frequently involved sites include the gingiva and alveolar mucosa. Histologically, fine black fibrillar or granular material distributed in the connective tissue or in a perivascular location with minimal or no inflammatory response is noted[89].

Smoker’s melanosis: Smoker’s melanosis is a specific entity characterized by black-brown hyperpigmentation of the oral cavity of heavy smokers[91]. Smoker’s melanosis is more common in women. The most common locations of smoker’s melanosis are the labial attached gingiva and interdental papillae[89-91].

Drug-induced mucocutaneous pigmentation: Diffuse pigmentation may be associated with systemic intake of drugs. The most common drugs associated with pigmentation include tetracyclines (minocycline), antimalarials (chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine), antifungals (ketoconazole), antimycobacterial agents (clofazimine), antiretroviral agents (zidovudine), chemotherapeutics (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and hydroxyurea), amiodarone, psychotropics (chlorpromazine), and oral contraceptives. Drug-induced oral pigmentation typically occurs following long-term medicine use and often resolves after cessation of the causative drug[5,89].

Melanotic macule: Melanotic macule is also known as focal melanosis. Unlike ephelides, melanotic macules do not darken with sun exposure[91]. Clinically, pigmented macules are typically solitary, well circumscribed lesions that average 6 mm in size. Histologically, increased melanin is predominantly present in the basal cell layer without an increase in the number of melanocytes. Incontinence of pigmentation and melanophages may be noted in the superficial lamina propria[89]. In contrast to simple lentigines, melanotic macules do not exhibit elongation of the rete ridges. In contrast to oral nevi or melanomas, melanotic macules are HMB-45 negative based on immunohistochemical staining[91,92].

Melanocytic nevus: Intraoral melanocytic nevi appear frequently during the third and fourth decades of life[91]. In general, the lesions are asymptomatic, pigmented macules or papules that are brown to black or blue in color. Histologically, approximately half of intraoral nevi cases classified as the intramucosal (intradermal) type, and another one-third of cases are blue nevi. Importantly, intraoral nevi share clinical similarities and a predilection for the hard palate with oral melanoma[91]. Therefore, a complete excision of all lesions is both practical and advisable.

Melanoacanthoma: Oral melanoacanthoma is considered a reactive process most frequently affecting black women in their third and fourth decades of life[13,89]. The buccal mucosa is the most commonly involved site, and most lesions are solitary. The clinical appearance is characterized by a sharply demarcated, irregularly textured pigmented plaque[91]. Histological examination reveals that large, dendritic melanocytes normally confined to the basal layer are instead dispersed throughout the epithelium[89].

Melanoma: Oral melanoma is uncommon, with a higher incidence in Asians, Hispanics, and blacks[93]. Oral melanoma is generally encountered in the fifth decade, with an increased incidence in men compared with women. A male-to-female ratio of 2.5-3.1 is reported among patients affected with oral melanoma[78,94]. Within the oral cavity, the most common site is the palate, followed by the anterior labial gingiva[94]. Clinically, oral melanoma is an asymptomatic, slow-growing, brown-to-black macule with irregular, asymmetric borders. Patients often present at an advanced stage with a rapidly enlarging mass with pain, ulceration, bleeding, mobile teeth, and bone involvement[78]. Histopathologically, oral melanoma is indistinguishable from cutaneous melanoma and exhibits epithelioid or spindle nuclei[91]. Pagetoid spread with large melanoma cells either singly or in nests can be noted in the superficial epithelium.

Any suspicious pigmentary lesion with irregular or asymmetric margins or those that are ulcerated, exophytic, or heterogeneous should be excised and assessed to exclude melanoma[78,92]. Dermoscopic findings include some malignant features, such as “blue-white veil”, irregular, asymmetrical, pinpoint, and hairpin patterns.

Physiological (racial) pigmentation: Physiological pigmentation or racial pigmentation is commonly identified in blacks, Asians, and other dark-skinned persons[4,12,91]. The attached gingiva is the most common location, but other sites including the tips of the fungiform papillae on the dorsal tongue may also be affected[13,89,91]. Physiological pigmentation of the oral cavity is typically diffuse, bilateral, and irregular in shape, commonly with poorly defined borders[89,91].

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: The most important differential diagnosis of LHS is Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) (Table 4). PJS is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyps, and cancer predisposition[49]. PJS is caused by mutations in the serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11) gene. PJS affects approximately one in 8300 individuals. Hyperpigmented macules on the lips, oral, perianal, genital mucosa, and acral skin are common[95]. PJS must be excluded because patients with PJS exhibit an increased incidence of gastrointestinal carcinoma as well as genital and mammary tumors. The lifetime risk of cancer in this condition is estimated to be 76%-85%[96]. Patients with PJS are recommended to undergo lifelong cancer surveillance, including colonoscopy, gastroduodenoscopy, and capsule endoscopy, as well breast imaging and gynecological assessment in women and testicular examination in men[97]. STK11 gene testing facilitates the differential diagnosis, ongoing management, and cancer surveillance[87].

| PJS | LHS | |

| Inheritance | Autosomal dominant (STK11 gene) | Sporadic and acquired |

| Age of onset | Birth to infancy | Adult onset |

| Shape of mucocutaneous pigmented macules | Freckle-like | Lenticular |

| Labial pigmentation | Very common | Very common |

| Oral pigmentation | Common | Very common |

| Perioral, perirhinal, or periorbital pigmentation | Common | Uncommon |

| Nail pigmentation | Uncommon | Very common |

| Acral skin pigmentation | Common | Common |

| Systemic involvement | Gastrointestinal polyposis | None |

| Risk of malignancy | Colon, gastric, small intestinal, pancreatic, breast, ovarian, thyroid, lung, and Sertoli cell (in men) cancers | None |

Addison’s disease: Addison’s disease is an endocrine disorder due to adrenocortical insufficiency. This disease affects approximately one in 100000 people. In developed countries, the disease is usually related to autoimmune disorders, whereas it is commonly associated with infection, especially tuberculosis, in developing nations[98].

Addison’s disease is characterized by hyperpigmentation of pressure exposed areas and associated with scanty body hair, hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, and elevated blood urea nitrogen[98]. Diffuse pigmentation may be noted on the skin, lip, oral cavity, conjunctiva, and genitalia. Labial and oral hyperpigmentation may be the first sign of the disease[12].

McCune-Albright syndrome: McCune-Albright syndrome is a sporadic disorder characterized by café-au-lait pigmentation on the skin, polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, and hyperfunctioning endocrinopathies including precocious puberty in women, Leydig and Sertoli cell hyperplasia in men, hyperthyroidism, excess growth hormone, and Cushing syndrome. The disorder is caused by a somatic mutation of the guanine nucleotide-binding protein, α-stimulating (GNAS) complex locus gene, leading to constitutive activation of the α subunit of the stimulatory G protein (Gsα)[99].

The most common locations of café-au-lait pigmentation include the posterior neck, sacrum, and head. The pigmentary lesions are light to dark brown macules and patches that may be segmental and tend to be unilateral. The size of café-au-lait pigmentation, which typically ranges from 0.5 to 20 cm, does not correlate with the extent of bone disease[100]. The pigmentation often covers a large geographic area with an irregular border that is frequently described as a “coast of Maine” border. A small increase in risk of malignancies in affected thyroid, bone, or pancreas tissues is noted[99].

Neurofibromatosis type 1: Neurofibromatosis type 1 is one of the most common human genetic diseases, occurring in approximately one of every 3000 births. No sex or race predilection is noted. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is an autosomal dominant inherited disease due to a mutation in the NF1 gene on the long arm of chromosome 17[101].

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is characterized primarily by café-au-lait pigmentation, multiple neurofibromas, optic glioma, iris Lisch nodules (pigmented hamartomas of the iris), central nervous system tumors, and bone malformations. The café-au-lait spots are yellow to dark brown macules that vary in diameter from a few millimeters to several centimeters[101]. Café-au-lait pigmentation in neurofibromatosis type 1 has characteristic smooth borders analogous to the “coast of California,” in contrast to the irregular borders of the café-au-lait pigmentation in McCune-Albright syndrome. Axillary or inguinal freckling (Crowe’s sign) is a highly suggestive sign. Although neurofibromas are benign tumors, plexiform neurofibromas may progress to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Other neoplasias frequently observed in neurofibromatosis type 1 patients include pilocytic astrocytomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, pheochromocytomas, and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia[102].

Carney complex: The Carney complex is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder associated with an inactivating mutation in the protein kinase, cAMP-dependent regulatory, type 1, α (PRKAR1α) gene located on chromosome 17 and a second genetic locus on chromosome 2p16 that produces a milder phenotype[103].

The Carney complex is characterized by lentigines, myxomas, endocrine tumors or overactivity, and schwannomas. Pale brown to black lentigines are the most common feature and are present in 70% to 80% of affected individuals. The frequently affected sites include the face, lips, conjunctiva, inner and outer canthi, and genital mucosa[99].

The most serious component of the Carney complex is life threatening cardiac myxoma, which causes death or serious disability in a significant percentage of patients. Spotty facial pigmentation is labeled as a marker of the Carney complex[91]. Therefore, early recognition of characteristic pigmentation leading to prompt assessment of the presence of cardiac myxoma can reduce mortality in affected individuals.

There is a strong association between the Carney complex and endocrine disease, including primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD)-associated Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, elevated prolactin, thyroid abnormalities, testicular large-cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumors, ovarian cystadenomas, and pancreatic lesions[99].

LEOPARD syndrome: LEOPARD syndrome is an autosomal dominant multisystemic disorder[104]. Mutations in the ubiquitous protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 11 gene (PTPN11), Raf-1 proto-oncogene (RAF1), B-Raf proto-oncogene (BRAF) or mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 gene (MAP2K1) are related to the syndrome[105].

The acronym “LEOPARD” refers to the presence of distinctive clinical features: Lentigines (L), electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities (E), ocular hypertelorism (O), pulmonary stenosis (P), genital abnormalities (A), retardation of growth (R), and sensorineural deafness (D).

Lentigines appear in early childhood and increase in number until puberty. Multiple well-defined brownish lentigines appear mostly on the neck, upper extremities, trunk, and below the knees. The face, scalp, palms, soles, and genitals may also be involved, but the mucosa is invariably unaffected. Typical lentigines are flat, small, dark brown macules that are histologically characterized by increased numbers of melanocytes and copious melanin production[105].

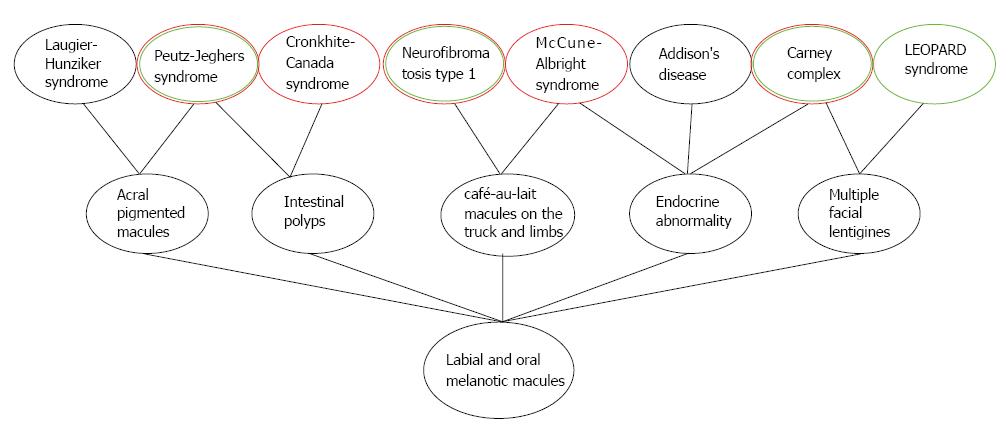

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is a nonhereditary condition characterized by cutaneous hyperpigmentation, alopecia, onychodystrophy, and diffuse gastrointestinal polyposis associated with diarrhea, abdominal pain, and proteinlosing enteropathy and malnutrition[106]. The condition occurs most frequently in middle-aged or older adults, with a slight male predominance, and a male-to-female ratio of 3:2[107]. Homogeneous, diffuse acral pigmentation is often noted in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, but no pigmentation is noted within the oral cavity[107,108]. In contrast to other polyposis syndromes, the polyps in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome patients can develop throughout the gastrointestinal tract (except the esophagus)[107]. To facilitate differential diagnosis, the relationships between several syndromes or systemic disorders characterized by diffuse mucocutaneous pigmentation are graphically illustrated in Figure 4.

Melanonychia can be found in a wide variety of conditions ranging from physiological pigmentation to life-threatening tumors (Table 5). Nail pigmentation in LHS should be distinguished from melanonychia caused by other disorders. The first and most important task is to determine whether the pigment is of melanocytic or nonmelanocytic origin. In most cases this task can be accomplished by clinical inspection and examination with a dermoscope[109].

| Causation of nail pigmentation | Condition | |

| Nonmelanocytic origin | Exogenous | Dirt |

| Tobacco | ||

| Tar | ||

| Potassium hypermanganate | ||

| Silver nitrate | ||

| Infectious | Bacterial infection | |

| (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | ||

| Onychomycosis | ||

| (fungal infection) | ||

| Traumatic | Subungual hemorrhage | |

| Subungual hematoma | ||

| Neoplastic | Hemangioma | |

| Melanocytic origin | Physiological | Ethnic (racial) melanonychia |

| Nutritional | Vitamin B12 deficiency | |

| Traumatic | Onychotillomania (nail biting) | |

| Frictional melanonychia | ||

| Iatrogenic | Systemic drug-induced melanonychia | |

| (e.g., zidovudine, hydroxyurea, and minocyline) | ||

| Radiotherapy-induced melanonychia | ||

| Inflammatory | Lichen planus | |

| Psoriasis | ||

| Endocrinic | Addison’s disease | |

| Pregnancy | ||

| Syndromic | LHS | |

| AIDS | ||

| Activated melanocytic | Benign melanocytic hyperplasia | |

| Lentigo simplex | ||

| Nevus | ||

| Neoplastic | Onychopapilloma | |

| Onychomatricoma | ||

| Bowen’s disease | ||

| Melanoma | ||

Exogenous pigmentation: Most exogenous pigmentation is due to dirt, tobacco, chemical agents, cosmetics, and topical therapeutic agents such as silver nitrate. Generally, exogenous pigmentation does not manifest as a longitudinal streak. Most of the pigmentation can be easily removed[109,110].

Onychomycosis: Onychomycosis may commonly present as nail pigmentation and abnormalities of the nail plate surface. White, yellow, green, or black changes in nails are due to fungal pigment that invades the nail plate. The most commonly responsible fungi include Scytalidium dimidiatum and Trichophyton rubrum var. nigricans[111].

Bacterial infection: Bacterial nail pigmentation, which is most commonly due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella and Proteus spp., exhibits a greenish or grayish hue and the discoloration is often confined to the lateral edge of the nail[110]. The pigmentation appears black to the naked eye, but it is clearly deep green when observed with a dermoscope.

Subungual hemorrhage and subungual hematoma: Typically, subungual hemorrhage or hematoma is due to a history of a single acute and heavy trauma. Dermoscopic findings typically involve a small reddish-black globular pattern and the proximal and lateral margins of the pigment[109]. Generally, subungual hematoma does not pose a diagnostic difficulty. However, it must be kept in mind that a tumor with neovascularization may bleed. Therefore, the presence of subungual blood should not be a sign used to exclude the diagnosis of melanoma[109,110].

Ethnic nail pigmentation: Ethnic or racial nail pigmentation is physiological longitudinal melanonychia observed in dark-skinned individuals[109]. Longitudinal melanonychia, which is distinctly uncommon in whites, has been reported to occur in 77%-96% of blacks and 11% of Asians[50]. Ethnic longitudinal melanonychia can present as single or multiple pigmented bands involving one or more digits.

Traumatic longitudinal melanonychia: The two common types of traumatic longitudinal melanonychia are nail pigmentation associated with onychotillomania (nail biting) and frictional melanonychia, which typically involves the fourth and/or fifth toenails due to friction with shoes[109].

Drug-induced melanonychia: Drug-induced longitudinal melanonychia appears as horizontal or longitudinal bands or as diffuse nail darkening[109]. The three most frequently responsible drugs include zidovudine, hydroxyurea, and minocycline[112].

Longitudinal melanonychia associated with inflammatory nail disorders: Multiple longitudinal melanonychia may occur in patients with lichen planus, which is typically associated with nail plate thinning, onychoatrophy, onychorrhexis, longitudinal splitting, longitudinal grooves or ridges of the nail plate, nail scarring, and abnormalities[19].

Nevus: Nail matrix nevi may be congenital or acquired and are typically observed in children and young adults. Generally, nail matrix nevi occur more often on fingernails compared with toenails. Typically, the width of the pigmented band of nail matrix nevi is 3 mm or less. Dermoscopic features of nail matrix nevi involve longitudinal parallel lines with a homogeneous brown color and regular spacing and thickness[113].

Bowen’s disease: Nonmelanocytic nail tumors may activate melanocytes resulting in longitudinal melanonychia. This entity is most commonly observed in association with Bowen’s disease[109]. Bowen’s disease or squamous cell carcinoma in situ is a slowly progressive malignancy.

Melanoma: Nail matrix melanoma is the most frequently observed melanoma subtype in blacks and Asians. It usually affects middle-aged or elderly individuals[109]. Nail matrix melanoma most frequently affects the index finger, the thumb, the large toe, or all of them[114].

Longitudinal melanonychia in malignancies is typically characterized by lesions wider than 5 mm, and gray to black streaks with variable color and shape within one lesion may occur in nail matrix melanoma. Moreover, nail dystrophy, nail erosion, and a bleeding mass strongly suggest a malignancy[110]. Brown or black pigmentation spreading from the nail bed, matrix and nail plate to the adjacent cuticle and proximal or lateral nail folds (Hutchinson’s sign) is a crucial clinical clue to diagnose or exclude melanoma[78].

Typically, the dermoscopic features of nail matrix melanoma include the absence of both homogeneity of both color and thickness of each longitudinal line, Hutchinson and micro-Hutchinson signs, and granular pigmentation[112,115].

In general, no treatment is required for LHS given the lack of associated systemic complications or malignant transformation. Patients may seek treatment for removal of labial hyperpigmented macules based on aesthetic consideration. Cryosurgery, Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers and Q-switched alexandrite lasers represent therapeutic options. Recurrence may occur after treatment. Sun protection is crucial to prevent reoccurrence[70].

LHS shares some features of labial, oral, and nail pigmentation with a variety of conditions. These conditions span a wide gamut from normal variation to a sign of an underlying life-threatening abnormality. Clinicians should be more familiar with typical features of these conditions and aware of important differential diagnosis, which contributes to obtaining an early final diagnosis. Accurate diagnosis is crucial to developing a reasonable medical strategy, including management options, malignant transformation surveillance, and psychological support. The evaluation involves a detailed history and physical examination, including visual inspection of all the affected sites. Dermoscopy and biopsy of any suspicious lesion should be performed for dermoscopic and histopathological evaluation. Other necessary tests or examinations may be considered in case of a difficult diagnosis. It is crucial that clinicians conduct long-term follow-up and surveillance due to the potential risks for malignant transformation and local severe complications in some conditions.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aksoy B, Fiorentini G, Jakhar D, Ziogas DE S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Laugier P, Hunziker N. [Essential lenticular melanic pigmentation of the lip and cheek mucosa]. Arch Belg Dermatol Syphiligr. 1970;26:391-399. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Nayak RS, Kotrashetti VS, Hosmani JV. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:245-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kemmett D, Ellis J, Spencer MJ, Hunter JA. The Laugier-Hunziker syndrome--a clinical review of six cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Siponen M, Salo T. Idiopathic lenticular mucocutaneous pigmentation (Laugier-Hunziker syndrome): a report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:288-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zuo YG, Ma DL, Jin HZ, Liu YH, Wang HW, Sun QN. Treatment of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome with the Q-switched alexandrite laser in 22 Chinese patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:125-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nikitakis NG, Koumaki D. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116:e52-e58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gencoglan G, Gerceker-Turk B, Kilinc-Karaarslan I, Akalin T, Ozdemir F. Dermoscopic findings in Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:631-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tamiya H, Kamo R, Sowa J, Haruta Y, Tanaka M, Ishii M, Kobayashi H. Dermoscopic features of pigmentation in Laugier-Hunziker-Baran syndrome. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:152-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ko JH, Shih YC, Chiu CS, Chuang YH. Dermoscopic features in Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Dermatol. 2011;38:87-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Wei Z, Li GY, Ruan HH, Zhang L, Wang WM, Wang X. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: A case report. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;119:158-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Veraldi S, Cavicchini S, Benelli C, Gasparini G. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: a clinical, histopathologic, and ultrastructural study of four cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:632-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mignogna MD, Lo Muzio L, Ruoppo E, Errico M, Amato M, Satriano RA. Oral manifestations of idiopathic lenticular mucocutaneous pigmentation (Laugier-Hunziker syndrome): a clinical, histopathological and ultrastructural review of 12 cases. Oral Dis. 1999;5:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zaki H, Sabharwal A, Kramer J, Aguirre A. Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome Presenting with Metachronous Melanoacanthomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Porneuf M, Dandurand M. Pseudo-melanoma revealing Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:138-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lenane P, Sullivan DO, Keane CO, Loughlint SO. The Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:574-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sterling GB, Libow LF, Grossman ME. Pigmented nail streaks may indicate Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Cutis. 1988;42:325-326. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Makhoul EN, Ayoub NM, Helou JF, Abadjian GA. Familial Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S143-S145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bisighini G, Davalli R. Malattia di Laugier: tre casi clinici (in Italian). Chron Dermatol. 1985;16:821-825. |

| 19. | Wang WM, Wang X, Duan N, Jiang HL, Huang XF. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: a report of three cases and literature review. Int J Oral Sci. 2012;4:226-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Revuz J, Clerici T. Penile melanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:567-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dupré A, Viraben R. Laugier’s disease. Dermatologica. 1990;181:183-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Seoane Lestón JM, Vázquez García J, Cazenave Jiménez AM, de la Cruz Mera A, Aguado Santos A. [Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. A clinical and anatomopathologic study. Presentation of 13 cases]. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1998;99:44-48. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Ayoub N, Barete S, Bouaziz JD, Le Pelletier F, Frances C. Additional conjunctival and penile pigmentation in Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: a report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:571-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pellerat J, Hermier C, Thivolet J, Vittori F. [Laugier’s labiojugal essential melanic pigmentation]. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:563-564. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Sartoris S, Pippone M, De Paoli MA, Cervetti O. Pigmentazione melanica idiopatica (in Italian). Giorn e Min Derm. 1975;110:382-385. |

| 26. | Laugier P, Hunziker N, Olmos L. [Essential melanic pigmentation of the mouth and the lips]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1977;104:181-184. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Baran R. Longitudinal melanotic streaks as a clue to Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1448-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bundino S, Zima AM. Pigmentazione melanica lenticolare essenziale della mucosa orale (Laugier). Studio di un caso al microscopio elettronico (in Italian). Giorn Ital Dermatol. 1979;114:145-148. |

| 29. | Bertazzoni MG, Botticelli A, Cimitan A. Su di un caso di pigmentazione melanica essenziale labio-buccale (M. di Laugier) (in Italian). Chron Dermatol. 1984;15:565-570. |

| 30. | Beurey J, Weber M, Jeandel C. Pigmentation melanique essentielle de la muqueuse gènitale: maladie de Laugier vulvaire (in French)? Med Hyg. 1986;44:786-790. |

| 31. | Baran R, Barrière H. Longitudinal melanonychia with spreading pigmentation in Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:707-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Koch SE, LeBoit PE, Odom RB. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:431-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Offidani A, Morroni M, Lazzaretti G, Mambelli V. [Histological and ultrastructural aspects of Laugier’s disease. Presentation of a case]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1987;122:535-538. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Borrello P, Toni F, Misciali C, Valeri F, Barone M. [A case of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1988;123:537-538. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Dal Tio R, Di Vito F, Grasso F. [Hyperpigmentation of the Laugier-Hunziker-syndrome type appearing during antineoplastic polychemotherapy]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1989;124:77-83. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Patrone P, Cafini G, Schianchi S, Passarini B. [Laugier-Hunzicker syndrome. Description of 3 cases]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1989;124:95-96. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Satriano RA. Pigmentazione melanica essenziale della mucosa orale e delle labbra (Malattia di Laugier-Hunziker) (in Italian). Chron Derm. 1989;21:743-745. |

| 38. | Golovinov ED. [A case of Laugier’s disease]. Vestn Dermatol Venerol. 1990;60-61. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Lamey PJ, Nolan A, Thomson E, Lewis MA, Rademaker M. Oral presentation of the Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Br Dent J. 1991;171:59-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gerbig AW, Hunziker T. Idiopathic lenticular mucocutaneous pigmentation or Laugier-Hunziker syndrome with atypical features. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:844-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mowad CM, Shrager J, Elenitsas R. Oral pigmentation representing Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Cutis. 1997;60:37-39. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Ferreira MJ, Ferreira AM, Soares AP, Rodrigues JC. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: case report and treatment with the Q-switched Nd-Yag laser. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:171-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yamamoto O, Yoshinaga K, Asahi M, Murata I. A Laugier-Hunziker syndrome associated with esophageal melanocytosis. Dermatology. 1999;199:162-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sheridan AT, Dawber RP. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: treatment with cryosurgery. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:146-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Began D, Mirowski G. Perioral and acral lentigines in an African American man. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:419, 422. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Kanwar AJ, Kaur S, Kaur C, Thami GP. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Dermatol. 2001;28:54-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Papadavid E, Walker NP. Q-switched Alexandrite laser in the treatment of pigmented macules in Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:468-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lampe AK, Hampton PJ, Woodford-Richens K, Tomlinson I, Lawrence CM, Douglas FS. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: an important differential diagnosis for Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:e77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Aytekin S, Alp S. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome associated with actinic lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:221-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Moore RT, Chae KA, Rhodes AR. Laugier and Hunziker pigmentation: a lentiginous proliferation of melanocytes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:S70-S74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Fisher D, Field EA, Welsh S. Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:312-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Akcali C, Serarslan G, Atik E. The Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. East Afr Med J. 2004;81:544-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Sabesan T, Ramchandani PL, Peters WJ. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: a rare cause of mucocutaneous pigmentation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:320-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ozawa T, Fujiwara M, Harada T, Muraoka M, Ishii M. Q-switched alexandrite laser therapy for pigmentation of the lips owing to Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:709-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ajith C, Handa S. Laugier-Hunziker pigmentation. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:354-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sardana K, Mishra D, Garg V. Laugier Hunziker syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:998-1000. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Tan J, Greaves MW, Lee LH. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome and hypocellular marrow: a fortuitous association? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:584-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Yago K, Tanaka Y, Asanami S. Laugier-Hunziker-Baran syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:e20-e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Blossom J, Altmayer S, Jones DM, Slominski A, Carlson JA. Volar melanotic macules in a gardener: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Simionescu O, Dumitrescu D, Costache M, Blum A. Dermatoscopy of an invasive melanoma on the upper lip shows possible association with Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:S105-S108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Aliagaoglu C, Yanik ME, Albayrak H, Güvenç SC, Yildirim U. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: diffuse large hyperpigmentation on atypical localization. J Dermatol. 2008;35:806-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Montebugnoli L, Grelli I, Cervellati F, Misciali C, Raone B. Laugier-hunziker syndrome: an uncommon cause of oral pigmentation and a review of the literature. Int J Dent. 2010;2010:525404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kim EJ, Cho SH, Lee JD. A Case of Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome. Ann Dermatol. 2008;20:126-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Pereira PM, Rodrigues CA, Lima LL, Reyes SA, Mariano AV. Do you know this syndrome? An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:751-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Sendagorta E, Feito M, Ramírez P, Gonzalez-Beato M, Saida T, Pizarro A. Dermoscopic findings and histological correlation of the acral volar pigmented maculae in Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. J Dermatol. 2010;37:980-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Lema B, Najarian DJ, Lee M, Miller C. JAAD Grand Rounds quiz. Numerous hyperpigmented macules of the oral mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:171-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Rangwala S, Doherty CB, Katta R. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:9. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Jabbari A, Gonzalez ME, Franks AG Jr, Sanchez M. Laugier Hunziker syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:23. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Sachdeva S, Sachdeva S, Kapoor P. Laugier-hunziker syndrome: a rare cause of oral and acral pigmentation. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:58-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Asati DP, Tiwari S. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Hyperpigmentation in Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. CMAJ. 2011;183:1402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Kosari P, Kelly KM. Asymptomatic lower lip hyperpigmentation from Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Cutis. 2011;88:235-236. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Wondratsch H, Feldmann R, Steiner A, Breier F. Laugier-hunziker syndrome in a patient with pancreatic cancer. Case Rep Dermatol. 2012;4:174-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Ergun S, Saruhanoğlu A, Migliari DA, Maden I, Tanyeri H. Refractory Pigmentation Associated with Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome following Er:YAG Laser Treatment. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:561040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Bhoyrul B, Paulus J. Macular pigmentation complicating irritant contact dermatitis and viral warts in Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:294-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Mahmood T, Menter A. The Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2015;28:41-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Fernandes D, Ferrisse TM, Navarro CM, Massucato EM, Onofre MA, Bufalino A. Pigmented lesions on the mucosa: a wide range of diagnoses. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119:374-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Lalosevic J, Zivanovic D, Skiljevic D, Medenica L. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome--Case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:223-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Fajre X, Aspillaga M, McNab M, Navarrete J, Sanhueza V, Benedetto J. [Laugier-Hunziker syndrome in a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome: Report of one case]. Rev Med Chil. 2016;144:671-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Barman PD, Das A, Mondal AK, Kumar P. Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome Revisited. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:338-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Voicu C, Cărbunaru A, Berevoescu M, Mihalcea O, Clătici VG. A rare association between Laugier-Hunziker, Sjogren syndromes and other autoimmune disorders-case report and literature review. Rom J Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;3:136-142. |

| 83. | Kaçar N, Yildiz CC, Demirkan N. Dermoscopic features of conjunctival, mucosal, and nail pigmentations in a case of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:23-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Abid MB, Mughal P, Abid MA. Anaemia with Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma. Singapore Med J. 2017;58:281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Paul J, Harvey VM, Sbicca JA, O’Neal B. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Cutis. 2017;100:E17-E19. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Verma B, Behra A, Ajmal AK, Sen S. Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome in a Young Female. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:148-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Duong BT, Winship I. The role of STK 11 gene testing in individuals with oral pigmentation. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Cusick EH, Marghoob AA, Braun RP. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: a case of asymptomatic mucosal and acral hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:27-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Müller S. Melanin-associated pigmented lesions of the oral mucosa: presentation, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:220-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Meleti M, Vescovi P, Mooi WJ, van der Waal I. Pigmented lesions of the oral mucosa and perioral tissues: a flow-chart for the diagnosis and some recommendations for the management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:606-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Eisen D. Disorders of pigmentation in the oral cavity. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:579-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Greenberg SA, Schlosser BJ, Mirowski GW. Diseases of the lips. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:e1-e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | McLaughlin CC, Wu XC, Jemal A, Martin HJ, Roche LM, Chen VW. Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer. 2005;103:1000-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 502] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Hicks MJ, Flaitz CM. Oral mucosal melanoma: epidemiology and pathobiology. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:152-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Tomlinson IP, Houlston RS. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet. 1997;34:1007-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Hearle N, Schumacher V, Menko FH, Olschwang S, Boardman LA, Gille JJ, Keller JJ, Westerman AM, Scott RJ, Lim W. Frequency and spectrum of cancers in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3209-3215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 508] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, Moslein G, Alonso A, Aretz S, Bertario L, Blanco I, Bülow S, Burn J. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 516] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Sarkar SB, Sarkar S, Ghosh S, Bandyopadhyay S. Addison’s disease. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:484-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Pichard DC, Boyce AM, Collins MT, Cowen EW. Oral pigmentation in McCune-Albright syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:760-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Collins MT, Singer FR, Eugster E. McCune-Albright syndrome and the extraskeletal manifestations of fibrous dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7 Suppl 1:S4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Cunha KS, Barboza EP, Dias EP, Oliveira FM. Neurofibromatosis type I with periodontal manifestation. A case report and literature review. Br Dent J. 2004;196:457-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Rosenbaum T, Wimmer K. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and associated tumors. Klin Padiatr. 2014;226:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Salpea P, Stratakis CA. Carney complex and McCune Albright syndrome: an overview of clinical manifestations and human molecular genetics. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;386:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Kalev I, Muru K, Teek R, Zordania R, Reimand T, Köbas K, Ounap K. LEOPARD syndrome with recurrent PTPN11 mutation Y279C and different cutaneous manifestations: two case reports and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:469-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Zhang J, Cheng R, Liang J, Ni C, Li M, Yao Z. Lentiginous phenotypes caused by diverse pathogenic genes (SASH1 and PTPN11): clinical and molecular discrimination. Clin Genet. 2016;90:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Suzuki R, Irisawa A, Hikichi T, Takahashi Y, Kobayashi H, Kumakawa H, Ohira H. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with myelodysplastic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5871-5874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Fan RY, Wang XW, Xue LJ, An R, Sheng JQ. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps infiltrated with IgG4-positive plasma cells. World J Clin Cases. 2016;4:248-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Wen XH, Wang L, Wang YX, Qian JM. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of six cases and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7518-7522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Braun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, Dalle S, Ronger S, Pandolfi R, Gaide O, French LE, Laugier P, Saurat JH. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:835-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Haneke E, Baran R. Longitudinal melanonychia. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:580-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Piraccini BM, Dika E, Fanti PA. Tips for diagnosis and treatment of nail pigmentation with practical algorithm. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:185-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Ronger S, Touzet S, Ligeron C, Balme B, Viallard AM, Barrut D, Colin C, Thomas L. Dermoscopic examination of nail pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1327-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Haenssle HA, Blum A, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Kreusch J, Stolz W, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, Brehmer F. When all you have is a dermatoscope- start looking at the nails. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Möhrle M, Häfner HM. Is subungual melanoma related to trauma? Dermatology. 2002;204:259-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Benati E, Ribero S, Longo C, Piana S, Puig S, Carrera C, Cicero F, Kittler H, Deinlein T, Zalaudek I. Clinical and dermoscopic clues to differentiate pigmented nail bands: an International Dermoscopy Society study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:732-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |