Published online Mar 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i3.119

Peer-review started: October 13, 2016

First decision: November 11, 2016

Revised: November 29, 2016

Accepted: January 16, 2017

Article in press: January 18, 2017

Published online: March 16, 2017

Processing time: 155 Days and 9.3 Hours

Castleman’s disease (CD), also known as angiofolicular lymph node hyperplasia, is a rare heterogenous group of lymphoproliferative disorders. Histologically, it can be classified as hyaline vascular type, plasma cell type, or mixed type. Clinically two different subtypes of the CD are present: Unicentric and multicentric. Unicentric CD is generally asymptomatic and associated with hyaline vascular type, and its diagnoses depend on the localized lymphadenopathy on examination or imaging studies. However, multicentric CD presents with generalized lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms including malaise, fever, night sweats, weight loss, and it is associated with the plasma cell type and mix type. Herein, we report a patient with unicentric CD of the plasma cell type without systemic symptoms, who developed end stage renal failure caused by amyloidosis 6 years after onset of CD.

Core tip: Castleman’s disease (CD), also known as angiofolicular lymph node hyperplasia, is a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders. The clinically unicentric form is generally asymptomatic and often associated with hyaline vascular type. The unicentric form of the disease often shows mild to moderate clinical prognosis, however the multicentric form is a more severe form. After the complete surgical removal of the lymph node, remission is achieved in many cases and complications are very rare. However, this case of unicentric CD of the plasma cell type is unique due to the fact that it presented with amyloidosis and end stage renal disease six years after the onset of the disease.

- Citation: Eroglu E, Kocyigit I, Unal A, Sipahioglu MH, Akgun H, Kaynar L, Tokgoz B, Oymak O. Unicentric Castleman’s disease associated with end stage renal disease caused by amyloidosis. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(3): 119-123

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i3/119.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i3.119

Castleman’s disease (CD), firstly described in 1956 by Castleman et al[1] as giant lymphoid hyperplasia or angiofolicular lymph node hyperplasia, is a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders. It is divided anatomically into unicentric and multicentric forms and histologically into plasma, hyaline vascular, and mixed cell types.

Unicentric Castleman’s disease (UCD) is mostly asymptomatic and is discovered when an enlarged lymph node is determined on physical examination or by imaging studies[2,3]. Conversely, multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) is a systemic disease with generalized peripheral lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, malaise, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Eighty to ninety percent of CD cases develop the hyaline vascular histological type, and it is commonly associated with UCD and clinically presents as a mediastinal or mesenteric mass. The plasma cell type (10%-20% of CD cases) accounts for the majority of multicentric cases and clinically presents with systemic symptoms due to increased inflammatory activity[3,4].

The pathogenesis of CD has not yet been completely clarified. The histopathological changes in lymph nodes resemble to the reactive changes that can be seen in response to normal antigenic stimuli. It has been shown that increased production of interleukin-6 (IL-6) might be related with the systemic inflammatory symptoms of CD. Unlike UCD, MCD is strongly associated with immunosuppression and human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) infection. The diagnosis is generally confirmed by excisional biopsy of the affected lymph node. Treatment of UCD is generally completed by resection of the lymph node; however, some cases need chemotherapy or immunotherapy[4,5].

Herein, we present the case of a male patient with UCD of the plasma cell type, which was diagnosed in 2010, with the excision of a paraaortic lymph node. Complete surgical resection was performed, and the patient was followed in a remission state for 3 years. Three years after he was lost to follow-up, the patient was admitted to hospital with increased creatinine levels, overt proteinuria, and increased inflammatory markers. A kidney biopsy showed AA-type amyloidosis. The patient was given hemodialysis due to end stage renal disease. Although the disease was in remission in imaging studies, this case presented with sudden kidney failure caused by amyloidosis, a rare complication of UCD of the plasma cell type.

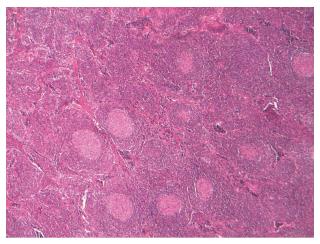

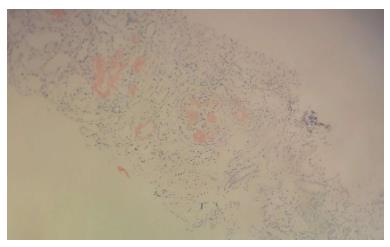

A 69-year-old man was admitted to hospital with abdominal discomfort, tenderness, and dyspeptic complaints in August 2010. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed paraaortic lymphadenopathy and the patient was referred to the hematology department. He had no history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, or alcohol use. The physical examination showed no sign of peripheral lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory results showed hypochromic microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 78 fl, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 66 mm/h, and C-reactive protein level of 64 mg/L (normal range: 0-6 mg/L). The reticulocyte count was normal. There was no iron, folic acid, or vitamin B12 deficiency according to the laboratory results. All biochemical parameters were within normal range. Serologic tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, Brucella, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and HHV-8 were all negative. Serum immunoelectrophoresis demonstrated polyclonal hyperglobulinemia. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed normocellular findings. A computed tomography scan demonstrated a paraaortic lymphadenopathy (6 cm in diameter). Total lymph node excision was performed and the result of the pathologic specimen was reported as Castleman’s disease of the plasma cell type (Figure 1). After operation, the patient was followed until July 2013, and he was in remission state according to laboratory and imaging studies. Follow-up laboratory results in 2011 showed that the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 55 mm/h and the C-reactive protein was 25 mg/L. Follow-up laboratory results in 2012 showed that the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 35 mm/h and the C-reactive protein level was 9.6 mg/L. During the patient’s last hematology visit in 2013, a physical examination revealed normal findings. Laboratory parameters showed that his hemoglobin level was 13.7 g/dL, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 33 mm/h, and the C-reactive protein level was 9.6 mg/L. All biochemical parameters were within normal range. Serum immunoelectrophoresis and protein electrophoresis were normal. Radiologically, there were millimetric lymph nodes in the paraaortic area. The patient stopped routine follow-up hematology visits after July 2013 and was not seen for three years due to the lack of complaints. In June 2016, the patient was admitted to the hematology department with complaints of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and edema in the distal extremities. A physical examination revealed pale skin and conjunctiva without hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory examinations revealed normochromic normocytic anemia (Hct, 25.7%; Hb, 9.6 g/dL; MCV, 87 fl) and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (80 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (76 mg/L). The results of the laboratory findings were as follows: Glucose 95 mg/dL, BUN 75 mg/dL, creatinine 6.2 mg/dL, Na 139 mmol/L, K 5.0 mmol/L, Ca 8.2 mmol/L, phosphorus 5.2 mmol/L, uric acid 6.6 mg/dL, total cholesterol 223 mg/dL, LDL 126 mg/dL, GGT 15 U/L, ALP 97 U/L, AST 10 U/L, ALT 6 U/L, total protein 5.9 g/dL, albumin 2.4 g/dL, LDH 213 U/L, CPK 20 U/L, and serum iPTH level 151 pg/mL (15-65). The urine stick test revealed a positive result for protein (+++), but there were no erythrocyte or leukocyte casts in the microscopic evaluation of the urine sediment. The 24-h urine protein level was 10 g. ANA, anti-ds DNA, anti-GBM and ANCA profiles were all negative. The patient did not have any chronic inflammatory conditions such as tuberculosis, malaria, rheumatoid arthritis, or familial Mediterranean fever. The patient was referred to the nephrology department. An abdomen ultrasonography noted normal sized kidneys and a normal parenchymal thickness with increased grade 2 renal cortical echogenicity. All other findings were normal. A kidney biopsy was performed, which suggested AA-type amyloidosis (Figure 2). Metabolic acidosis and uremic symptoms had occurred, oliguria developed, and creatinine clearance was decreased to 10 mL/dk. The patient was admitted for veno-venous hemodialysis intervention via a double-lumen dialysis catheter in the jugular vein. Hematologic assessment demonstrated that CD was in remission according to imaging studies. A PET-CT scan only reported multiple millimetric lymph nodes without FDG uptake in the paraaortic area. Hemodialysis intervention was continued three times a week due to progressive deterioration of kidney functions. The patient was discharged from hospital two weeks later with a hemodialysis catheter and followed weekly. Two months later, he was considered to have end stage renal disease and underwent routine hemodialysis intervention via a created arteriovenous fistula.

Although renal involvement is a potential complication of CD, this rare case of UCD of the plasma cell type presented with renal failure caused by amyloidosis 6 years after the onset of the disease.

UCD is generally asymptomatic and sometimes comes to clinical attention if an enlarged lymph node is demonstrated on physical examination or in imaging studies. UCD more frequently affects one lymph node area. Systemic symptoms (i.e., malaise fever, night sweats, and weight loss) are generally limited to patients with the less common plasma cell type[2,3]. Although 10% to 20% of UCD cases are of the plasma cell type, MCD is generally associated with the plasma cell type and closely linked to systemic inflammatory symptoms and renal complications[2,6]. Interestingly, our patient with UCD of the plasma cell type had no constitutional symptoms but was complicated by secondary amyloidosis 6 years after diagnosis and remission. This case illustrates the unexpected clinical course of CD.

Leung et al[7] reported a patient with MCD of the plasma cell type, who developed acute-on-chronic renal failure caused by renal amyloidosis 15 years after onset of CD and ultimately end stage renal disease. In UCD, surgical resection of the tumor results in a resolution of systemic symptoms and normalization of laboratory abnormalities. However, repeated renal biopsies show no evidence of regression of amyloid deposits in cases with UCD[8]. Androulaki et al[9] described a patient with UCD complicated with systemic AA-type amyloidosis which regressed with surgical resection. In contrast, Gaduputi et al[10] reported a case with UCD in a submandibular mass that was complicated by systemic amyloidosis and surgical resection failed to regress the amyloidosis. Intriguingly, our patient presented with amyloidosis 6 years after surgical resection of the localized disease. However, his disease was in remission radiologically, and we believe that low-grade inflammation may be responsible for the amyloidosis in this patient. We speculate that low-grade inflammation exists in patients with CD of the plasma cell type.

Renal manifestations associated with CD are heterogeneous, including, minimal change disease, membranous, mesangio-proliferative, crescentic, membrano-proliferative glomerulonephritis, interstitial nephritis, and amyloidosis[11]. El Karoui et al[12] investigated the renal involvement by kidney biopsy of 19 French patients and found 20% of the patients (4/19) had renal amyloidosis. They concluded that the most common renal histologic findings were small-vessel lesions. Xu et al[13] recently reported the renal involvement in 76 Chinese patients with CD and they concluded that CD of the multicentric type, plasma cell type or mixed types is often associated with renal complications. Although previous case reports have showed that in patients with CD and renal manifestations, 25 of 64 patients had amyloidosis according to the current English literature, they did not report any patients with CD and renal amyloidosis in their cohort. They also demonstrated that thrombotic microangiopathy-like lesions are the most common pathological characteristics[13]. These findings suggest that amyloidosis may be histologically rare but clinical presentation of amyloidosis in patients with CD is more severe than other renal involvements.

This UCD case of the plasma cell type is unique due to renal failure caused by amyloidosis having occurred after 6 years of disease onset while the patient was in remission radiologically. In conclusion, physicians should be careful in terms of the presence of an inflammatory state and amyloidosis although a patient may be in radiological remission.

A 69-year-old man with Castleman’s disease (CD) presented with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and edema in the distal extremities.

There were pale skin and conjunctiva without hepatosplenomegaly and also, pitting edema in distal extremities.

Nephrotic syndrome, lymphoma, and congestive heart failure.

Increased serum creatinine, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, decreased hemoglobin and albumin levels were revealed in laboratory examinations.

A positron-emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan only reported multiple millimetric lymph nodes without fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the paraaortic area.

AA-type amyloidosis.

Previous case reports of patients with CD and renal manifestations have documented 25 of 64 patients had amyloidosis according to the current English literature. Amyloidosis may be histologically rare but clinical presentation of amyloidosis in patients with CD is more severe than other renal involvements.

CD is a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders, which is described by Benjamin Castleman et al. Clinically two different subtypes of the CD are present, unicentric CD (UCD) and multicentric CD (MCD). UCD presents with localized lymphadenopathy. MCD, however, presents with generalized lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms. PET-CT is used to determine lesions and FDG is a radiolabeled sugar molecule which is taken by lesion/lesions.

UCD of the plasma cell type may present with renal failure caused by amyloidosis while the disease is in remission radiologically. Physicians should be careful in terms of the presence of an inflammatory state and amyloidosis development in patients with CD.

In this manuscript, the authors report on a case of unicentric CD associated with end stage renal disease caused by amyloidosis. This case report is clinically interesting.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Markic D, Tanaka H, Watanabe T, Yorioka N S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP. Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer. 1956;9:822-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Talat N, Belgaumkar AP, Schulte KM. Surgery in Castleman’s disease: a systematic review of 404 published cases. Ann Surg. 2012;255:677-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Keller AR, Hochholzer L, Castleman B. Hyaline-vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locations. Cancer. 1972;29:670-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mylona EE, Baraboutis IG, Lekakis LJ, Georgiou O, Papastamopoulos V, Skoutelis A. Multicentric Castleman’s disease in HIV infection: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Rev. 2008;10:25-35. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Leger-Ravet MB, Peuchmaur M, Devergne O, Audouin J, Raphael M, Van Damme J, Galanaud P, Diebold J, Emilie D. Interleukin-6 gene expression in Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1991;78:2923-2930. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Maslovsky I, Uriev L, Lugassy G. The heterogeneity of Castleman disease: report of five cases and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci. 2000;320:292-295. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Leung KT, Wong KM, Choi KS, Chau KF, Li CS. Multicentric Castleman’s disease complicated by secondary renal amyloidosis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2004;9:392-393. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Keven K, Nergizoğlu G, Ateş K, Erekul S, Orhan D, Ertürk S, Tulunay O, Karatan O, Ertuğ AE. Remission of nephrotic syndrome after removal of localized Castleman’s disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:1207-1211. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Androulaki A, Giaslakiotis K, Giakoumi X, Aessopos A, Lazaris AC. Localized Castleman’s disease associated with systemic AA amyloidosis. Regression of amyloid deposits after tumor removal. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:55-57. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gaduputi V, Tariq H, Badipatla K, Ihimoyan A. Systemic Reactive Amyloidosis Associated with Castleman’s Disease. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2013;7:476-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chan TM, Cheng IK, Wong KL, Chan KW. Resolution of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis complicating angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman’s disease). Nephron. 1993;65:628-632. [PubMed] |

| 12. | El Karoui K, Vuiblet V, Dion D, Izzedine H, Guitard J, Frimat L, Delahousse M, Remy P, Boffa JJ, Pillebout E. Renal involvement in Castleman disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:599-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xu D, Lv J, Dong Y, Wang S, Su T, Zhou F, Zou W, Zhao M, Zhang H. Renal involvement in a large cohort of Chinese patients with Castleman disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27 Suppl 3:iii119-iii125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |