Published online Sep 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9.469

Revised: June 3, 2014

Accepted: June 27, 2014

Published online: September 16, 2014

Processing time: 148 Days and 0.2 Hours

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a severe adverse drug reaction, which is characterized by erythema, blisters, and/or erosions of the mucous membranes and skin, but intestinal involvement is rare. In contrast, pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI) is a rare condition associated with a wide variety of underlying diseases, but to date no patient has presented with PCI associated with TEN. A 55-year-old man was admitted to intensive care unit for treatment of TEN caused by phenobarbital. On day 8 after admission, he presented with progressive abdominal distention and hypotension. Computed tomography (CT) showed gas in the superior mesenteric vein and air filled cysts in the walls of the small intestine. He was suspected of having septic shock due to PCI. As there were no indications of bowel ischemia or necrosis, the patient was managed conservatively with antibiotics and oxygen therapy. On day 10 after admission, he was weaned off catecholamines, with CT on day 11 showing complete resolution of gas in the superior mesenteric vein and air filled cysts. To our knowledge, this article describes the first patient presenting with PCI associated with TEN.

Core tip: Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a severe adverse drug reaction, which affects skin and mucosa of whole body. However, intestinal involvement is rare documented. We report the case of a 55-year-old man with toxic epidermal necrolysis caused by phenobarbital. He was diagnosed with pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis during the clinical course. Although septic shock was accompanied, conservative treatment was effective. To our knowledge, this article describes the first patient presenting with pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Citation: Yao SY, Seo R, Nagano T, Yamazaki K. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(9): 469-473

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i9/469.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9.469

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare but potentially fatal condition often caused by adverse drug reactions. TEN is characterized by high fever, widespread blistering of the exanthematous macules and atypical target-like lesions of the skin, as well as mucosal involvement. However, there have been few reports of intestinal involvement of TEN[1].

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI) is a rare condition, in which submucosal or subserosal gas cysts are found in the walls of the small and/or large intestines. The pathogenesis of PCI remains unclear, and the role of emergency surgical intervention in patients with PCI accompanied by portal vein gas or peritoneal irritation remains controversial.

We describe here a patient with PCI encountered during the clinical course of TEN, with the former condition successfully treated by conservative management. To our knowledge, this is the first such patient described to date.

A 55-year-old man with a previous medical history of alcohol-induced epilepsy presented to our dermatology department with complaints of fever and a rapidly evolving rash over his face and trunk. He had been taking two antiepileptic agents, carbamazepine and phenobarbital, for one month. Drug induction was suspected, and oral antihistamine and steroids were started after discontinuation of the antiepileptics.

Despite this treatment, the rash did not improve, spreading to his back, arms, and legs after one week. He was admitted to our hospital with a presumed diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). On the day of admission, he was started on intravenous steroid pulse therapy with prednisolone plus immunoglobulin. However, blister and erosion continued to spread throughout the entire body (Figure 1). The patient was diagnosed with TEN and transferred to intensive care unit (ICU) on day 6 of hospitalization. During his stay in the ICU, his skin condition gradually improved with continuous intravenous steroids. He was also administered a first generation cefem for antibiotic prophylaxis.

Abdominal distension was also observed, beginning on the third day of admission. CT scan performed on day 5 showed no specific findings except for pneumocolon. The patient was put on a bowel regimen, consisting of laxatives and enemas, to regulate his bowel movements.

On day 8, the condition of this patient suddenly deteriorated. His abdominal distension became exacerbated and his blood pressure decreased rapidly. He became less responsive and scored 11 (E2V4M5) on the Glasgow Coma Scale.

Physical examination showed a temperature of 37.2 °C, blood pressure of 60/28 mmHg, pulse of 110 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% in ambient air. Abdominal examination showed marked fullness and diffuse rebound tenderness throughout the entire abdomen. Laboratory examinations revealed severe acidosis and elevated lactic acid concentration. The results of laboratory examinations are shown in Table 1. A blood culture was positive for a species of Corynebacterium.

| Laboratory investigation | Results | Reference ranges |

| Arterial blood gas | ||

| Blood pH | 7.121 | 7.42 ± 0.04 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 24.5 | 32-46 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 83.6 | 74-100 |

| Base excess (mmol/L) | -7.3 | -2-2 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 2.6 | 0.44-1.78 |

| Plasma bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 15.6 | 21-29 |

| Serum chemistry | ||

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 1.6 | 3.8-5.1 |

| Asparate aminotransferase (IU/mL) | 28 | 9-35 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/mL) | 14 | 5-36 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 85 | 6-22 |

| Creatine (mg/dL) | 2.61 | 0.47-0.79 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 10.3 | 0-0.5 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 104 | 70-109 |

| Blood count | ||

| WBC (/μL) | 7.4 × 103 | 3.9-9.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.5 | 13.4-17.6 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 30.4 | 39-52 |

| Platelet count (/μL) | 7.9 × 104 | 13-37 |

| Prothrombin time-INR | 1.17 | 0.9-1.1 |

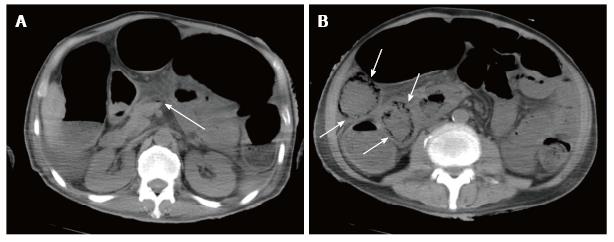

Plain abdominal radiography showed small-bowel distension and a low-density linear and bubbly pattern of gas in the small-bowel wall (Figure 2). A non-contrast CT scan revealed gas in the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and intramural air, but no free air, in the small-bowel wall (Figure 3). The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with septic shock associated with pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. He was started immediately on oxygen treatment, followed by intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and catecholamine. Although an emergency laparotomy was considered, the patient’s general condition was too poor to tolerate an operation, and there was no sign of bowel ischemia or necrosis. Therefore, the patient was managed conservatively.

The patient progressed well, recovering from a catecholamine-dependent state two days later. A CT scan, performed three days later, showed that the gas in the small bowel wall had completely disappeared. The abdominal fullness gradually remitted and he was discharged from the ICU after sixteen days. Several days later, a drug lymphocyte stimulating test (DLST) was positive for phenobarbital, indicating that phenobarbital had caused TEN in this patient.

The patient’s skin condition completely resolved sixty-two days after admission. No recurrence of PCI and TEN have been observed for three years.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN are rare diseases, affecting approximately 1 or 2 per million individuals annually. Both of these diseases are considered medical emergencies as they are potentially fatal[2].

Currently, TEN and SJS are considered to be at the two ends of a spectrum of severe epidermolytic adverse cutaneous drug reactions, differing only in their extent of skin detachment. Symptoms of SJS include acute conditions characterized by mucous membrane erosions and skin lesions (described as macules, atypical target-like lesions, bulla, and erosions) involving less than 10% of the total skin surface area, whereas TEN involves more than 10% of the total skin surface area. In addition to skin symptoms, both diseases are often accompanied by complications in numerous organs, including the liver, kidneys, and lungs. The mortality rate for patients with TEN has been reported to range from 25% to 35%[2,3].

Certain drugs, including sulfonamides, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cephem antibiotics, barbiturates, and antiepileptics are the most frequent triggers of TEN. A DLST for phenobarbital was positive in this patient, and the TEN was retrospectively determined to be a drug eruption caused by phenobarbital, with the condition progressing to TEN from SJS during its clinical course.

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI) is an unusual intestinal condition characterized by the presence of gas within the intestinal wall, usually in the mucosa and submucosa of the small and large intestines. PCI has been classified as primary or secondary, with most patients having secondary PCI due to an underlying condition[4]. These underlying conditions have been classified as (1) traumatic and mechanical (e.g., pyloric stenosis, endoscopy, enteric tube placement volvulus, surgical anastomosis, carcinoma); (2) inflammatory and auto- immune (e.g., Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, diverticular disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, polydermatomyositis, scleroderma, mixed connective tissue disease, multiple sclerosis); (3) infectious (e.g., Clostridium difficile, HIV/AIDS, cytomegalovirus, Mycobacterium species); (4) pulmonary (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, cystic fibrosis); (5) drug induced (e.g., cytotoxic agents, immunosuppressants, corticosteroids); or (6) other conditions, such as transplantation, graft versus host disease, leukemia, or intestinal infarction[5].

The pathogenesis of PCI is unclear, although several hypotheses have been suggested. The gas within the intestine wall may be intraluminal, pulmonary or produced by bacteria[5,6]. Mechanical features thought to be responsible for intrusion of intraluminal gas into the bowel wall are mucosal injury and/or increased intraluminal pressure. The possibility of pulmonary gas as a source for PCI is based on the hypothesis that air migrates along vessels within the mediastinum, retroperitoneum and mesentery after alveolar rupture in pulmonary diseases.

PCI may be asymptomatic or may manifest symptoms and signs associated with life threatening complications, such as bowel ischemia, perforation and peritonitis. Generally, however, the symptoms of PCI are mild and include abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, abdominal distension, bloody stools and/or weight loss. About 3% of patients experience more serious symptoms, including bleeding, ileus, volvulus, intussusception, and/or pneumoperitoneum[7].

Treatment for PCI depends on its symptoms, with no specific treatment standardized. PCI may be detected incidentally by radiographic imaging, screening colonoscopy, or during laparotomy. Intramural gas cysts in asymptomatic patients usually resolve spontaneously over time. Patients with mild to moderate symptoms are usually treated conservatively, with antibiotics, oxygen, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy reported effective[8,9]. Emergency surgical exploration is indicated for patients with suspected intestinal necrosis or abdominal sepsis[10]. Immediate surgery has been indicated for patients with elevated C-reactive protein or WBC, or the signs of sepsis, bowel perforation or portal venous gas. Conservative therapy has been recommended for patients with normal or slightly increased inflammatory parameters in blood samples and no signs of sepsis, bowel perforation or free gas[11].

Since the first report of PCI in France in the 18th century, numerous case reports and reviews have appeared worldwide. However, intestinal lesions in patients with TEN have rarely been reported. To our knowledge, our patient is the first reported to have TEN associated with PCI. Four patients with TEN were reported to present with digestive symptoms, including abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. Pathological examination of mucosal biopsy specimens revealed that the superficial epithelium was severely damaged by necrosis, while the lamina propia was relatively unaffected[1].

PCI has been reported associated with collagen skin diseases, including scleroderma and dermatomyositis[10,12]. These patients are often treated with corticosteroids, which can induce atrophy of the mucosa and mucosal defects facilitating the intrusion of gas and bacteria[13].

Our patient was treated intravenously with high dose corticosteroids for 15 d, which may have exacerbated the atrophy and necrosis of the intestinal mucosa, which had been damaged by TEN. Persistent constipation may result in chronically elevated intra-luminal pressure, inducing the invasion of intramural compartments by gas and bacteria. The fragility of his intestinal mucosa allowed bacterial translocation and resulted in septic shock of Corynebacterium.

The signs of peritoneal irritation and gas in the SMV suggested the need for an emergency laparotomy, but his poor general condition did not allow surgery. In addition, we were unable to identify any underlying disease that could have induced ischemia or necrosis of the intestine. Conservative treatment with antibiotics, catecholamine, and oxygen therapy was successful. His abdominal symptoms disappeared and he discharged from the ICU after 8 d. In general, patients with signs of peritonitis in addition to metabolic acidosis indicating septic shock are candidates for surgery. However, in the absence of life-threatening situations such as perforation or necrosis, PCI can be managed conservatively. PCI is a clinical sign, and is not itself a diagnosis. Careful evaluation of the underlying disease and accompanying symptoms is essential.

The authors thank edanz.Ltd who provided medical writing services.

A 55-year-old male patient under the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis presented abdominal distension and fell into state of shock.

The patient was diagnosed with pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis.

Perforative peritonitis, acute mesenteric artery occlusion.

The patient had severe acidosis (a blood pH of 7.121), acute renal damage (blood urea nitrogen 85 mg/dL, creatine 2.61 mg/dL) and elevated C-reactive protein (10.3 mg/dL).

A non-contrast computed tomography scan revealed gas in the superior mesenteric vein and intramural air in the small-bowel wall.

No pathological specimen was obtained but a blood culture was positive for a species of Corynebacterium, showing that the patient had been in the state of sepsis due to pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis.

Conservative management including oxygen treatment, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and catecholamine was successful.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a severe adverse drug reaction, which is characterized by erythema, blisters, and/or erosions of the mucous membranes and skin in whole body, but intestinal involvement is rare reported.

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis can be observed during the treatment course of toxic epidermal necrolysis and conservative management is possibly effective when there are no signs of ischemia or necrosis of the intestine.

This is an interesting case report of pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis. The manuscript is clearly written, and this unusual presentation has clinical relevance.

P- Reviewer: Bourgoin SG, Chen GS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Chosidow O, Delchier JC, Chaumette MT, Wechsler J, Wolkenstein P, Bourgault I, Roujeau JC, Revuz J. Intestinal involvement in drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet. 1991;337:928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yamane Y, Aihara M, Ikezawa Z. Analysis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japan from 2000 to 2006. Allergol Int. 2007;56:419-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | KOSS LG. Abdominal gas cysts (pneumatosis cystoides intestinorum hominis); an analysis with a report of a case and a critical review of the literature. AMA Arch Pathol. 1952;53:523-549. [PubMed] |

| 5. | St Peter SD, Abbas MA, Kelly KA. The spectrum of pneumatosis intestinalis. Arch Surg. 2003;138:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Galandiuk S, Fazio VW. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. A review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:358-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tak PP, Van Duinen CM, Bun P, Eulderink F, Kreuning J, Gooszen HG, Lamers CB. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis in intestinal pseudoobstruction. Resolution after therapy with metronidazole. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:949-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Togawa S, Yamami N, Nakayama H, Shibayama M, Mano Y. Evaluation of HBO2 therapy in pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2004;31:387-393. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Braumann C, Menenakos C, Jacobi CA. Pneumatosis intestinalis--a pitfall for surgeons? Scand J Surg. 2005;94:47-50. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Schröpfer E, Meyer T. Surgical aspects of pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: two case reports. Cases J. 2009;2:6452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Balbir-Gurman A, Brook OR, Chermesh I, Braun-Moscovici Y. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis in scleroderma-related conditions. Intern Med J. 2012;42:323-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Höer J, Truong S, Virnich N, Füzesi L, Schumpelick V. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: confirmation of diagnosis by endoscopic puncture a review of pathogenesis, associated disease and therapy and a new theory of cyst formation. Endoscopy. 1998;30:793-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |