Published online Jul 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i7.311

Revised: March 6, 2014

Accepted: May 16, 2014

Published online: July 16, 2014

Processing time: 280 Days and 23.5 Hours

We investigated the sebaceous gland metaplasia (SGM) of the esophagus and clarified the evidence of misdiagnosis and its diagnosis pitfall. Cases of pathologically proven SGM were enrolled in the clinical analysis and reviewed description of endoscope. In the current study, we demonstrated that SGM is very rare esophageal condition with an incidence around 0.00465% and an occurrence rate of 0.41 per year. There were 57.1% of senior endoscopists identified 8 episodes of SGM. In contrast, 7.7% of junior endoscopists identified SGM in only 2 episodes. Moreover, we investigated the difference in endoscopic biopsy attempt rate between the senior and junior endoscopist (P = 0.0001). The senior endoscopists had more motivation to look for SGM than did junior endoscopists (P = 0.01). We concluded that SGM of the esophagus is rare condition that is easily and not recognized in endoscopy studies omitting pathological review.

Core tip: Cases of pathologically proven sebaceous gland metaplasia (SGM) of the esophagus were enrolled in the clinical analysis and reviewed the description of endoscope. It is very rare esophageal condition with an incidence around 0.00465% and an occurrence rate of 0.41 per year. There are 57.1% of senior endoscopists identified 8 episodes of SGM and 7.7% of junior endoscopists identified SGM in only 2 episodes. The senior endoscopist had more motivation to look for SGM than did junior endoscopists. We concluded SGM of the esophagus is rare condition that is easily and not recognized in endoscopy studies omitting pathological review.

- Citation: Chiu KW, Wu CK, Lu LS, Eng HL, Chiou SS. Diagnostic pitfall of sebaceous gland metaplasia of the esophagus. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(7): 311-315

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i7/311.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i7.311

Sebaceous gland metaplasia (SGM) tends to be found incidentally during autopsy or esophageal resection[1,2]. From the point of differential diagnosis of esophageal lesions, SGM becomes of scientific interest during endoscopic studies. Endoscopists should take the first look at unusual lesions[3]. Although several reports have attempted to determine whether SGM is the result of a metaplastic process or a congenital anomaly, histological examination of endoscopic biopsies is traditionally used to make a pathological diagnosis in clinical practice[2]. Biopsied tissues can be taken for histological and marker studies of SGM[4,5]. Due to the benign nature of SGM-containing endoscopic readings[6], the diagnosis is commonly missed when tissue biopsies are not reviewed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to clarify the incidence of SGM and identify the hallmarks of SGM in endoscopic review.

From January 1, 1998 to June 30, 2012, a total of 215046 patients underwent endoscopic procedures with 35302 tissue biopsies taken by 33 endoscopists in the endoscopy unit of Kaohsiung Chang Memorial Hospital. The endoscopic procedures included 864 esophagoscopiesand 214182 gastroscopies (include 650 nasoendoscopies). Cases of endoscopic ultrasound of the upper gastrointestinal tract, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and double-balloon enteroscopy via an oral route were excluded from this study. The cases of pathologically proven SGM were enrolled in the clinical analysis and the endoscopic characteristics were reviewed.

By definition, an endoscopist with more than 20 years of experience was defined as a senior endoscopist, while an endoscopist with less than 20 years of experience was defined as a junior endoscopist. Accordingly, 7 senior and 26 junior endoscopists were identified. The senior endoscopists performed 110022 (51.2%) endoscopic studies and 16012 (14.5%) endoscopic biopsies, and the junior endoscopists performed 105046 (48.8%) endoscopic studies and 19290 (18.4%) endoscopic biopsies. Histological examinations of the endoscopic biopsies were performed by an experienced pathologist.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 12.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Comparisons of the endoscopic biopsy parameters and SGM frequency between the senior and junior endoscopists were performed using the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

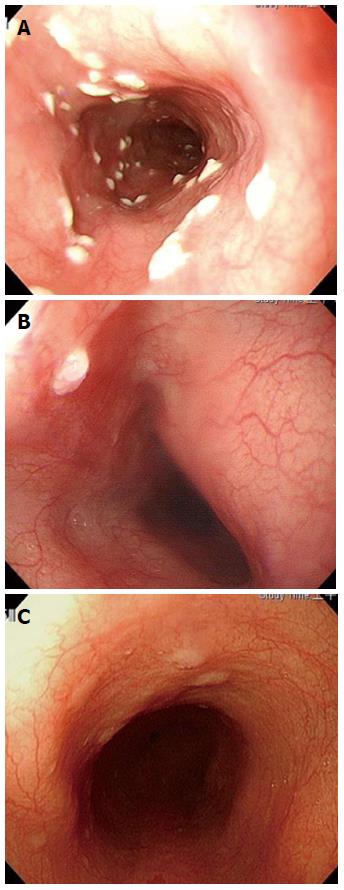

Among the 215046 endoscopic studies performed during the study period, there were 6 cases of pathologically documented SGM in 10 endoscopic studies (Table 1). The incidence and occurrence rates were 0.00465% was 0.41 per year, respectively. The male to female ratio was 3:1, and the mean age was 57.6 years (range 46-71 years). Four of the 6 cases with SGM came from a health screening center, and the other 2 came from outpatient clinics. All of the cases had numerous tiny yellowish lesions with histopathological examination identified heterotopic sebaceous gland located in the middle-lower esophagus (Figure 1).

| Case | Sex | Age | 1st visit | Source | Symptom | 1st ESP | 1st End. Dx | Biopsy | Review | 2nd ESP | 2nd End. Dx | Biopsy | Review |

| 1 | M | 46 | 1998 | Outpatient | Peptic | Senior 1 | Xanthoma | SGM | + | ||||

| 2 | M | 71 | 1999 | Health screen | Denied | Senior 1 | SGM | SGM | + | ||||

| 3 | M | 60 | 2002 | Outpatient | Peptic | Senior 1 | SGM | SGM | + | Senior 2 | Xanthoma | - | - |

| 4 | M | 65 | 2002 | Health screen | Denied | Senior 2 | Papilloma | SGM | - | Senior 4 | Papilloma | - | - |

| 5 | F | 49 | 2008 | Health screen | Denied | Junior 2 | Candidiasis | SGM | - | Junior 1 | Negative | - | - |

| 6 | F | 55 | 2012 | Health screen | Denied | Senior 3 | Candidiasis | - | - | Senior 3 | Xanthoma | SGM | + |

The primary endoscopic impression was xanthoma (by senior 1, 2 and 3) in 3 cases, candidiasis (by junior 2 and senior 3) in 2 cases, papilloma (by senior 2 and senior 4) in 2 cases, and a negative description (by junior 1) in 1 case (Table 1). No cases of SGM were recognized by the senior endoscopists 1, 2, 3 and 4 or junior endoscopists 1 and 2 in the primary endoscopic study, and no cases (0/3) of SGM were recognized by senior endoscopists 2 or 4 or junior endoscopist 1 in the secondary endoscopic impression without tissue pathology review (Table 1). The rate improved after pathological review, there was a 100% (2/2) positive diagnosis experienced in the case 2 and case 3 in the primary endoscopic impression by senior 1, and only 3.03% (1/33) of our endoscopists did it.

Among the 6 pathologically confirmed cases of SGM, 5 were diagnosed in the first endoscopic study by tissue biopsy, while the sixth case was diagnosed in the second endoscopic study by tissue biopsy (Table 1). Among the 7 senior endoscopists who performed 110022 (51.2%) endoscopies, 16012 (14.5%) endoscopic biopsies were performed, an average of 2287 biopsies per senior endoscopist and 4 (57.1%) cases diagnosed of SGM in 8 episodes by senior 1 of 3 times, senior 2 of 2 times, senior 3 of 2 times, and senior 4 in 1 time. In contrast, of the 105024 (48.8%) endoscopies performed by 26 junior endoscopists, 19290 (18.4%) endoscopic biopsies were performed, an average of 741.9 biopsies per junior endoscopists, and identified-2 (7.7%)cases SGM in only 2 episodes by junior 1 and junior 2 respectively. Significantly fewer endoscopic biopsies were performed by the senior endoscopists than by the junior endoscopists (P = 0.0001), and significantly more cases of HSGM were identified by senior endoscopists than by junior endoscopists (P = 0.01) (Table 2).

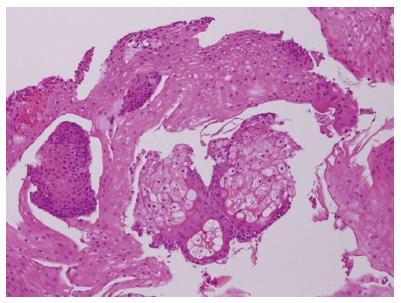

Endoscopic biopsy showed multiple light yellow plaques 2-5 mm in diameter with clustering distribution that embedded the surface of the esophagus (Figure 1). In 100% (6/6) of cases, sebaceous glands were located at the lower to middle esophagus. Pathological analysis revealed stratified squamous epithelium with lobules of sebaceous glands abutting the lower epithelium. No associated polymorphic nuclear or cellular infiltration was noted (Figure 2).

The present study demonstrated that SGM is a very rare esophageal condition with an incidence around 0.00465% and an occurrence rate of 0.41 per year. There was no doubt of the pathological diagnosis of SGM[7,8], but endoscopic biopsy should make an important impact on the incidence of SGM. In the real world, endoscopic biopsy is performed by endoscopists for 2 possible reasons: a suspected malignant lesion, or a lesion that is difficult to identify under endoscopic study. Such lesions look benign, especially in narrow band imaging[9,10], we believed that endoscopists does not perform biopsy, if they macroscopically diagnosed the lesion for benign. It may be a reason for the incidence of SGM is likely underestimated.

In the current study, senior endoscopist 1 encountered SGM 3 times (cases 1, 2 and 3) in 1998, 1999 and 2002. After the endoscopic biopsy and pathological review in the first case, a 100% (2/2) endoscopic diagnosis rate of senior endoscopist 1 was noted in cases 2 and 3. In contrast, senior endoscopist 2 missed an endoscopic diagnosis in a xanthoma due to a lack of pathological review despite the first case being proven. Senior endoscopist 2 also missed an endoscopic diagnosis in a papilloma that was biopsied but not pathologically reviewed.

In the meantime, senior endoscopist 4 also missed an endoscopic diagnosis in a papilloma in case 4 due to lack of pathological review. In SGM cases 5 and 6, the primary endoscopic diagnosis of candida esophagitis was made by junior endoscopist 2 and senior endoscopist 3. Junior endoscopist 2 had performed an endoscopic biopsy in case 5, but senior endoscopist 3 did not in case 6.

Due to the lack of a pathological review, junior endoscopist 1 made a negative endoscopic diagnosis in case 5 during a scheduled health screen. In contrast, senior endoscopist 2 also missed the endoscopic diagnosis in SGM case 6 due to the lack of a response to candida infection treatment in the follow-up clinic. Because endoscopic biopsy and pathological review were both performed, 6 cases of SGM were documented in our series.

Our series showed that 66.7% of the cases of SGM came from health screening centers, and for these cases the pathology reports were not returned to the ordering endoscopist. In addition, the interpreting doctor at the health screening center was not the original endoscopist, and the patients did not return to the outpatient clinic due to there being no evidence of malignancy. To overcome the diagnostic underestimation demonstrated here, endoscopists need to actively follow up each pathological report after an endoscopic biopsy, or a computer management system should send the final pathological report to the original endoscopist on a weekly basis. Therefore, the accurate diagnosis of SGM requires both endoscopic biopsy and pathological review[11].

Studies have reported that candida infection (Figure 3A) is the most common endoscopic diagnosis to appear as SGM[7,8]. In the present study (Table 1), 10 episodes of SGM were found at a rate of 3 in xanthomas, 2 in candida infections, and 2 in papillomas (Figure 3B). The same situation was the first impression as candida infection of the esophagus but no medication response to it in our case 6[12]. SGM case 6 was determined by a subsequent pathological review. For most endoscopists, the first impression would be glycogenic acanthosis (Figure 3C), potentially with minor atypical features. All of the above situations belong to the benign nature of the etiology of SGM, and the symptoms of SGM are not alarming enough to warrant an endoscopic biopsy. Therefore, missing endoscopic diagnosis occurs easily in situations in which both endoscopic biopsy and pathological review are not both performed.

An interesting finding in the current study was the difference in endoscopic biopsy attempts between the senior and junior endoscopists. More cases were examined by the senior endoscopists than by the junior endoscopists (51.2% vs 48.8%), in contrast to the endoscopic biopsy rate (14.5% vs 18.4%). The large difference in the number of biopsies taken by senior (21.2%) vs junior endoscopists (78.8%) might give a false impression in statistical analysis. Senior endoscopists had a 3-fold higher number of endoscopic biopsies compared to the junior endoscopists (2287.4 vs 741.9 endoscopic biopsies per endoscopist). Senior endoscopists had more motivation to look for SGM than the junior endoscopists. Anyway, SGM is a very rare endoscopically indistinct benign finding in the esophagus. The histogenesis of ectopic sebaceous glands in the esophagus is unknown; whilst it could be a congenital abnormality, a majority of authors defined it like an acquired metaplastic process. No malignant transformation has yet been reported. From the pathologists’ point of view an inflammatory or neoplastic process has to be excluded as the cause of the non-distinctive endoscopic findings[8,13]. In our recent study found that senior endoscopists are more interested than junior endoscopist, in look for the esophagus SGM cells as well as the attempt for endoscopic biopsy[14].

In conclusion, asymptomatic esophageal SGM is a rare condition that occurs in old age (> 50 years) and is male dominant. A differential diagnosis of a benign non-inflammatory nature should be kept in mind in daily practice with endoscopic biopsies and pathological review but may be never seen clinically.

Sebaceous gland metaplasia of esophagus tends to be found incidentally because of the usually no symptoms.

It is hard to make a clinical diagnosis due to the silent disease.

Endoscopic biopsy with pathological review is very important for the differential diagnosis from the other esophageal pathologies.

Histological examination with HE stained showed characteristic sebaceous differentiation.

Endoscopy demonstrated numerous tiny rounded, elevated, white-yellowish lesions distributed at the middle and lower esophagus.

Histopathological examination identified numerous sebaceous glands were located in the lamina propria, revealed lobules of cells that showed characteristic sebaceous differentiation.

Because there were no esophageal symptoms or/and eating problems, the patient did not require endoscopic surgery or other treatment.

A sebaceous cell of presumed ectodermal origin, in the esophageal mucosa, which is of endodermal origin, is of scientific interest. Different theories may explain the existence of this peculiarity by sebaceous gland metaplasia is the most plausible.

Sebaceous gland metaplasia tends to be found incidentally during autopsy or esophageal resection.

This is a well designed and well written case report which may be interesting for gastroenterologists and other clinicians.

P- Reviewers: Alsolaiman M, Bugaj AM, Huerta-Franco MR S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Zak FG, Lawson W. Sebaceous glands in the esophagus. First case observed grossly. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1153-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nakanishi Y, Ochiai A, Shimoda T, Yamaguchi H, Tachimori Y, Kato H, Watanabe H, Hirohashi S. Heterotopic sebaceous glands in the esophagus: histopathological and immunohistochemical study of a resected esophagus. Pathol Int. 1999;49:364-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bambirra EA, de Souza Andrade J, Hooper de Souza LA, Savi A, Ferreira Lima G, Affonso de Oliveira C. Sebaceous glands in the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:251-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakada T, Inoue F, Iwasaki M, Nagayama K, Tanaka T. Ectopic sebaceous glands in the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:501-503. [PubMed] |

| 5. | van Esch E, Brennan S. Sebaceous gland metaplasia in the oesophagus of a cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). J Comp Pathol. 2012;147:248-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Grube-Pagola P, Vicuña-González RM, Rivera-Salgado I, Alderete-Vázquez G, Remes-Troche JM, Valencia-Romero AM. [Ectopic sebaceous glands in the esophagus. Report of three cases]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34:75-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thalheimer U, Wright JL, Maxwell P, Firth J, Millar A. Sebaceous glands in the esophagus. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marín-Serrano E, Jaquotot-Herranz M, Casanova-Martínez L, Tur-González R, Segura-Cabral JM. Ectopic sebaceous glands in the esophagus. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:141-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ide E, Maluf-Filho F, Chaves DM, Matuguma SE, Sakai P. Narrow-band imaging without magnification for detecting early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4408-4413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kawai T, Takagi Y, Yamamoto K, Hayama Y, Fukuzawa M, Yagi K, Fukuzawa M, Kataoka M, Kawakami K, Itoi T. Narrow-band imaging on screening of esophageal lesions using an ultrathin transnasal endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27 Suppl 3:34-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fukuchi M, Tsukagoshi R, Sakurai S, Kiriyama S, Horiuchi K, Yuasa K, Suzuki M, Yamauchi H, Tabe Y, Fukasawa T. Ectopic Sebaceous Glands in the Esophagus: Endoscopic Findings over Three Years. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:217-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hoshika K, Inoue S, Mizuno M, Iida M, Shimizu M. Endoscopic detection of ectopic multiple minute sebaceous glands in the esophagus. Report of a case and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:287-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Suttorp AC, Heike M, Fähndrich M, Reis H, Lorenzen J. Talgdrüsenheterotopie im Ösophagus. Der Pathologe. 2013;34:162-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chiu KW, Chiu SS. Endoscopic biopsy as a quality assurance for the endoscopic service. Plos one. 2013;11:e78557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |