Published online Oct 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i29.109516

Revised: June 11, 2025

Accepted: July 22, 2025

Published online: October 16, 2025

Processing time: 104 Days and 3.8 Hours

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) primarily causes hepatic inflammation and has various clinical manifestations. However, extrahepatic reactions, ranging from localized or systemic inflammation, may occur in some cases. Here, we report a case of an acute exacerbation of chronic HBV infection with atypical extrahepatic mani

A 53-year-old woman visited a clinic due to worsening skin rash and mucosal inflammation. She was receiving antiviral therapy due to a recent acute exacerbation of chronic HBV infection. While liver function was improving with anti

Clinicians should recognize mucocutaneous manifestations of chronic HBV, as systemic steroids may yield favorable outcomes.

Core Tip: Our case report highlight that extrahepatic manifestations affecting the skin and mucosa can occur in chronic hepatitis B patients, even during nucleotide analogue treatment, and may be effectively managed with systemic steroids, likely targeting immune complex-mediated inflammation.

- Citation: Kim JW, Park SY, Kim NI, Choi SK, Yoon JH. Mucocutaneous manifestation mimicking vasculitis in chronic hepatitis B: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(29): 109516

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i29/109516.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i29.109516

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection causes intrahepatic inflammation, eventually leading to cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. Chronic HBV (CHB) infection affects approximately 270 million people worldwide[2]. In Korea, CHB prevalence reached 7.2% in the 1980s but has been steadily decreasing to 2.7% since the HBV vaccine was introduced in 1983. However, CHB prevalence is still high at 4%-5% in people aged > 40 years, requiring active management and treatment to prevent intrahepatic complications.

Hepatitis B is a hepatotropic virus that typically causes various hepatic diseases, although some patients develop extrahepatic manifestations, including polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), glomerulonephritis, and cutaneous manifestations[3]. The critical pathogenic mechanisms responsible for most extrahepatic manifestations are not well understood but are thought to involve an immune response to HBV, including the deposition of immune complexes (ICs) in target tissues and systemic inflammation[4]. Therefore, nucleotide analogs (NAs) can be administered to inhibit HBV replication and improve symptoms in cases of extrahepatic manifestations. Although treatment with NAs is expected to improve mild extrahepatic manifestations, immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents can be required to manage more severe renal, neurological, and hematological manifestations[1].

Herein, we report a case of atypical unclassified extrahepatic HBV infection manifestation, confined to the skin and mucosa, due to an acute exacerbation of CHB infection despite antiviral treatment, which was improved with systemic steroids. Additionally, we provide a respective literature review.

A 53-year-old woman, who had CHB infection not undergoing antiviral therapy, presented to our clinic with new-onset jaundice and nausea.

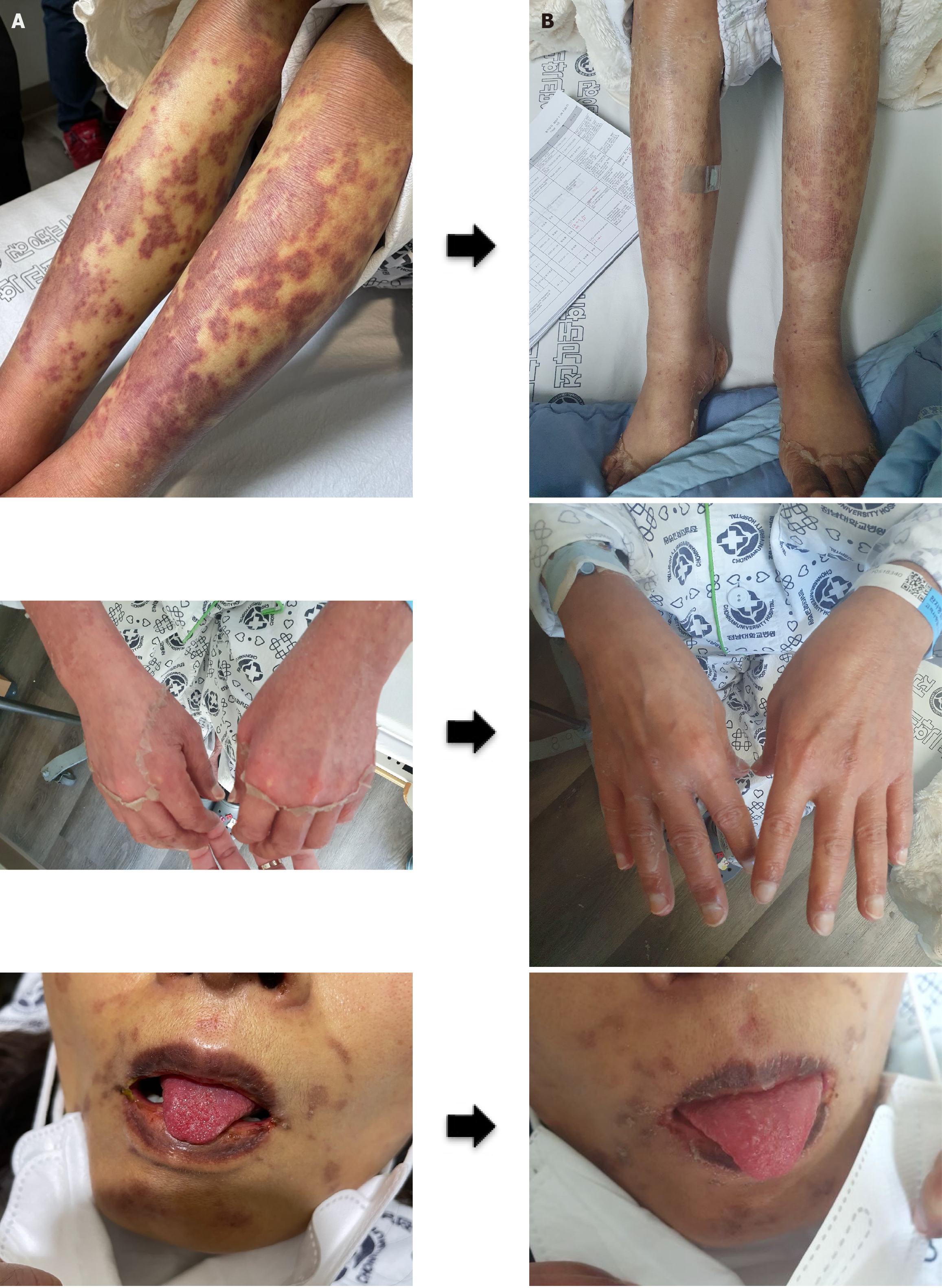

Laboratory results (Supplementary Table 1) indicated an acute exacerbation of CHB, prompting the initiation of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Consequently, CT scans revealed the presence of newly developed massive ascites, prompting referral for management of potential acute liver failure. Thus, she was referred to our institution for the management of possible acute liver failure. Although liver function progressively improved during the 42 days of follow-up, skin rash significantly worsened, leading to hospitalization. At diagnosis, the rash was present on both thighs and spread to the forearms, face, and abdomen. On admission, mild erythematous purpuric macules and crusts of variably sizes were present on both arms, legs, face, and abdomen. She also complained of mild pain in the lower extremities but no joint pain. Inflammatory mucosal findings such as strawberry tongue, xerostomia, vaginal discharge, and conjunctivitis were present, but oral ulcers were absent (Figure 1).

She had no comorbidities other than CHB.

The patient exhibited no significant medical or medication history, and her family history was unremarkable.

The patient’s vital signs at admission were systolic blood pressure 108 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure 63 mmHg, body temperature 36.5℃, and heart rate 105 beats per minute. A physical examination revealed the presence of scleral jaundice and skin lesions mentioned above.

On the day of admission, the patient’s laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 9600/mm² and progressive anemia, with hemoglobin reduced to 10.8 g/dL. The platelet count had declined to 73000/mm³, indicating thrombocytopenia. Hepatic function tests showed marked improvement compared to prior values (Supplementary Table 1), with aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels decreased to 83 IU/L and 59 IU/L, respectively, and total bilirubin lowered to 7.99 mg/dL (direct bilirubin 4.3 mg/dL). However, hypoalbuminemia (2.9 g/dL) and coagulopathy (INR 2.02) persisted, reflecting ongoing hepatic synthetic dysfunction. Renal function was mildly impaired, with a creatinine level of 1.29 mg/dL. Besides low C4 Levels (< 8.0 mg/dL, normal range; 17.1-46.5 mg/dL), no other autoimmune-related findings (ANCA/ANA or rheumatoid factor) were observed.

Abdomen computed tomography scans revealed acute parenchymal liver disease with massive ascites, which was absent before (Supplementary Figure 1).

Preliminary diagnoses were rendered on the basis of the skin lesions, and these included mixed cryoglobulinemic vas

Due to the continuous worsening of extrahepatic manifestations, we decided to add systemic steroids. Considering the conventional use of prednisone at 1-1.5 mg/kg for the management of vasculitis and extrahepatic manifestations, including PAN, the decision was made to administer prednisolone at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg in response to the exacerbation of mucocutaneous symptoms. Consequently, a cumulative dose of 62.5 mg of methylprednisolone was subsequently administered.

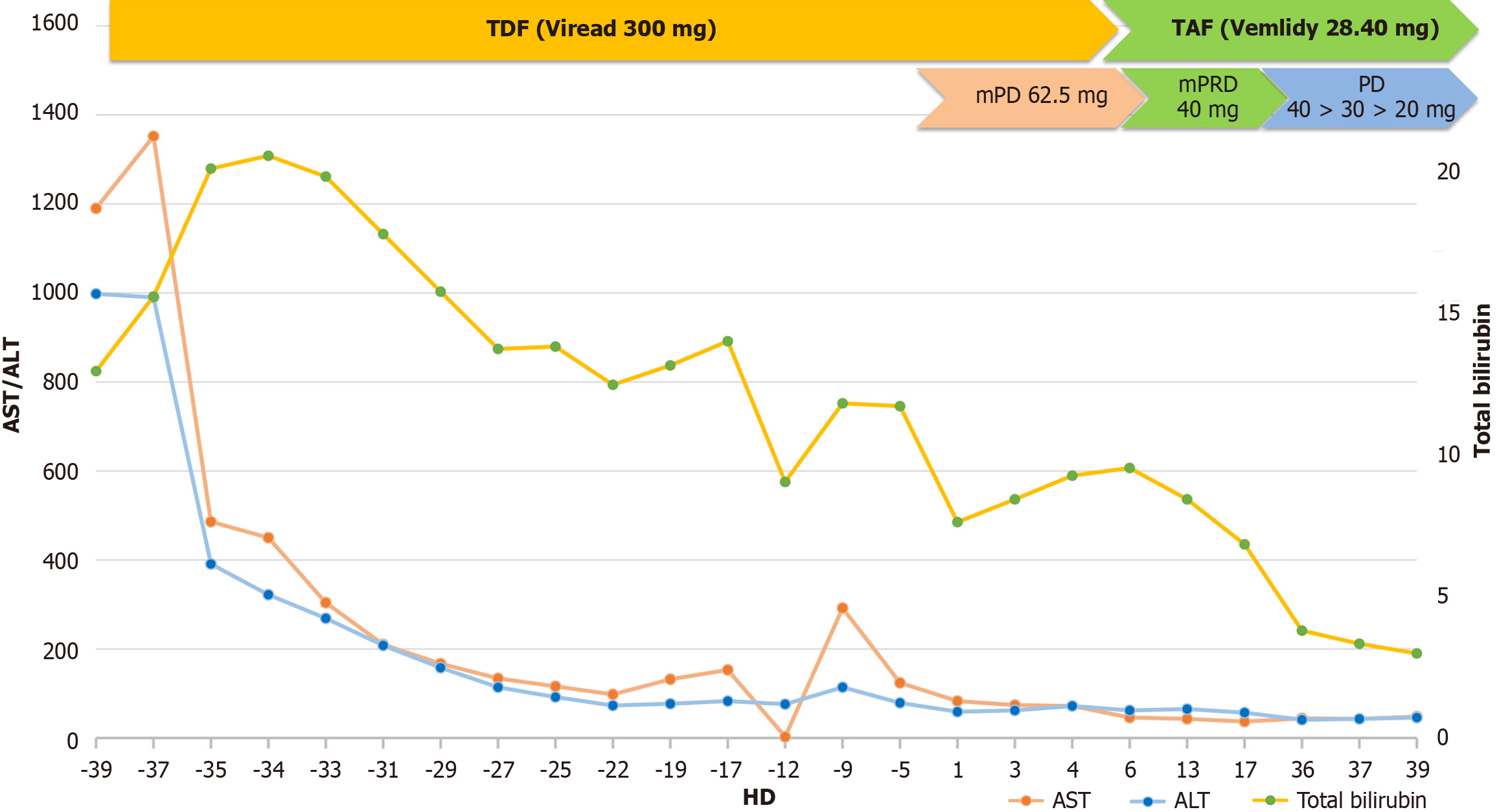

After approximately 2 weeks on intravenous high-dose methylprednisolone (62.5 mg), a rapid improvement in skin symptoms was noted. Methylprednisolone was tapered 50 mg for 5 days, followed by switching to oral prednisolone, which was tapered by 10 mg every 1 week. Despite concerns about HBV exacerbation during treatment, the favorable trend in liver function continued (Figure 2) and as the skin lesions improved rapidly without ulceration (Figure 1), the patient was discharged.

CHB infection continues to be a significant global health concern, affecting approximately 250 million people worldwide with a prevalence of around 2%–5%[1]. HBV, which is primarily a hepatotropic virus[3], induces diverse clinical forms of liver disease, varying from asymptomatic carrier to severe fulminant hepatitis[4]. Particularly, HBV is a leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma. In HBV-endemic regions, such as Asia-Pacific countries, approximately 80% of newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinomas are associated with chronic HBV infection[2]. Therefore, efforts to mitigate the impact of HBV have focused primarily on prevention, treatment, surveillance, and care, actually reducing the HBV prevalence[5].

However, the effects of HBV are not limited to the liver. Indeed, there are extrahepatic or systemic inflammatory responses associated with HBV infection. Although the exact pathophysiology underlying these extrahepatic manifestations remains unclear, IC formation, triggered by the surge in viral load or HBV reactivation, is thought to play a significant role[6]. This theory is supported by the marked decrease in the incidence of HBV-related PAN after HBV vaccination was introduced.9 Moreover, treatment with NAs to suppress HBV DNA improves liver-related symptoms in most patients with HBV-related cryoglobulinemic vasculitis[6,7]. Although HBV is a viral infection, corticosteroids or cytotoxic agents such as cyclophosphamide are often used to manage systemic symptoms in patients with HBV-associated PAN or cryoglobulinemic vasculitis[8]. However, these immunosuppressive therapies may promote HBV reactivation by impairing immune control[9]. Accordingly, several guidelines, including those from the European Association for the Study of the Liver, recommend preemptive antiviral therapy in patients with chronic HBV un

In the presented case, the patient demonstrated severe extrahepatic manifestations concurrent with HBV reactivation, primarily involving the skin and mucosa. This suggests an IC-mediated reaction based on the literature typically indicating an improvement in extrahepatic symptoms following NA treatment[6]. Despite decreased viral titers after antiviral therapy, the patient's extrahepatic symptoms worsened. After initiating systemic steroids, skin and mucosal lesions rapidly improved without any sequelae. Although the patient had achieved effective viral suppression with continuous NA therapy, cutaneous symptoms appeared later in the disease course[11]. These findings suggest that immune reconstitution, marked by the restoration of HBV-specific T-cell responses, may play a role in the emergence or exacerbation of immune complex–mediated vasculitis[12-14]. Another potential factor to consider is the non-cytolytic immune activation triggered by HBV antigen persistence despite undetectable viremia, especially in the context of previous immune escape variants or low-level viral replication in extrahepatic tissues[12,13]. The clinical experience from this case suggests that monitoring should not be limited to viral load but should also encompass immune-inflammatory and organ-specific indices, even in virologically suppressed patients. Typical HBV extrahepatic manifestations include serum sickness-like syndrome with fever, rash, and myalgia; glomerulonephritis; polyarthritis; and PAN, a type of vasculitis[6]. The specific findings of each extrahepatic manifestation differ in clinical symptoms, diagnostic modality, and treatment (Table 1)[6,15]. However, the diagnostic criteria did not fit any known extrahepatic manifestations in this case. The patient showed generalized skin rash and inflammatory mucosal lesions in the oral cavity, vagina, and conjunctiva without joint or renal involvement. Furthermore, immunologic serum tests were normal. The histologic examination showed no findings typical for vasculitis in the skin biopsy.

| Reported condition | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment | Prognosis | Histology | Treatment response |

| Mixed cryoglobulinemia vasculitis | Arthralgia (non-deforming, bilateral, symmetrical); Palpable purpura; Raynaud’s phenomenon; sicca syndrome | Presence of serum cryoglobulin; low complement levels (especially C4) | Antiviral therapy; B-cell–depleting therapy (Rituximab); Corticosteroids; Plasma exchange; Removal of circulating cryoglobulins; Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | In rare cases, life-threatening, affecting; the central nervous system, the gastrointestinal tract, and the heart | Immune complex-mediated small-vessel vasculitis characterized by leukocytoclastic infiltration and complement deposition, typically involving the skin, kidneys, and peripheral nerves. C4 is markedly decreased | Antiviral therapy leads to improvement in vasculitic symptoms, though immunosuppressives (e.g., rituximab) may be necessary for refractory cases. Prognosis improves with viral suppression |

| Serum sickness-like syndrome | Fever (< 39°C); skin rash (erythematous, macular, maculopapular, urticarial, nodular, or petechial lesions), polyarthritis | Clinical diagnosis | Antiviral therapy | Occurs before the onset of acute HBV hepatitis symptoms and tends to regress with the onset of hepatitis symptoms | Immune complex–mediated hypersensitivity reaction involving IgM and complement deposition, mimicking type III hypersensitivity. Unlike classic serum sickness, cryoglobulins and hypocomplementemia are typically absent | Symptoms generally improve spontaneously or with supportive care. Antiviral therapy hastens resolution when associated with acute HBV |

| Non-rheumatoid arthritis | Asymmetric skin erythema within the first 3 months of hepatitis onset | Anti-CCP (5%); ANA (10%); RF (25%) | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Improvement within days of treatment | Transient arthritis without erosive joint changes, possibly immune-mediated in response to HBV antigens. Lacks autoantibodies seen in rheumatoid arthritis (e.g., anti-CCP) | Responds rapidly to NSAIDs. Symptoms resolve within days and rarely recur after viral clearance |

| Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) | Polyarthritis, polyarthralgia, rash, fever, livedo reticularis, abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, peripheral nervous system involvement, and hypertension | Biopsy (arteritis or aneurysms in medium-sized arteries); ANCA (−) | Combinations of antiviral drugs, corticosteroids, and plasma exchange | HBV-related PAN is characterized by fewer relapses but has higher mortality than the non-HBV form | Necrotizing inflammation of medium-sized arteries with transmural fibrinoid necrosis; biopsy confirms arteritis or microaneurysms. Often associated with HBV surface antigen–antibody immune complex deposition | Requires antiviral therapy combined with corticosteroids and/or plasma exchange. Prognosis improves significantly with viral suppression |

| Glomerulopathies (MN/MPGN) | Proteinuria; renal failure | Decreased of C3 and C4 Level; biopsy (microspherular substructures) | Antiviral treatment; corticosteroids | Renal involvement improves after HBsAg clearance, but the disease may progress to chronic renal failure in a small number of patients | Deposition of immune complexes (HBsAg-HBsAb) in glomerular basement membrane, leading to mesangial and subendothelial inflammation. Complement (C3/C4) often reduced | Antiviral therapy improves renal outcomes in most cases. Some progress to chronic kidney disease despite HBsAg clearance |

The diagnostic challenge introduced in this case emphasizes the complex systemic nature of HBV infection. The patient’s symptoms suggested possible vasculitis, but extensive evaluation revealed none, highlighting the complex clinical presentations of HBV infection. This case highlights the need for a holistic approach to HBV management, encouraging clinicians to consider both hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations in CHB patients.

This case study has several limitations. The hypothesis regarding the etiology of the skin lesions was primarily based on the clinical presentation and the patient’s response to treatment, and subsequently evaluated through blood tests and histological examination. The absence of cryoglobulin testing limits the ability to definitively exclude mixed cryoglobulinemia as a differential diagnosis. However, the patient exhibited no signs of fever or joint pain and only presented with mucosal involvement, which did not align with the known extrahepatic manifestations of CHB. As a result, the clinical findings were categorized as unclassified manifestations. And cryoglobulin testing was not performed based on the atypical symptom pattern and the absence of hallmark features indicative of cryoglobulinemia at the time of presentation.

In conclusion, our findings highlight that extrahepatic manifestations affecting the skin and mucosa can occur in CHB patients, even during NA treatment, and may be effectively managed with systemic steroids, likely targeting IC-mediated inflammation.

| 1. | Abbas Z, Siddiqui AR. Management of hepatitis B in developing countries. World J Hepatol. 2011;3:292-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhu RX, Seto WK, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific Region. Gut Liver. 2016;10:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chuang YC, Tsai KN, Ou JJ. Pathogenicity and virulence of Hepatitis B virus. Virulence. 2022;13:258-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:S13-S21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 747] [Cited by in RCA: 637] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang Q, Qi W, Wang X, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Qin S, Zhao P, Guo H, Jiao J, Zhou C, Ji S, Wang J. Epidemiology of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Infections and Benefits of Programs for Hepatitis Prevention in Northeastern China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mazzaro C, Adinolfi LE, Pozzato G, Nevola R, Zanier A, Serraino D, Andreone P, Fenoglio R, Sciascia S, Gattei V, Roccatello D. Extrahepatic Manifestations of Chronic HBV Infection and the Role of Antiviral Therapy. J Clin Med. 2022;11:6247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mazzaro C, Dal Maso L, Urraro T, Mauro E, Castelnovo L, Casarin P, Monti G, Gattei V, Zignego AL, Pozzato G. Hepatitis B virus related cryoglobulinemic vasculitis: A multicentre open label study from the Gruppo Italiano di Studio delle Crioglobulinemie - GISC. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:780-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ramos-Casals M, Stone JH, Cid MC, Bosch X. The cryoglobulinaemias. Lancet. 2012;379:348-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mazzaro C, Dal Maso L, Visentini M, Gitto S, Andreone P, Toffolutti F, Gattei V. Hepatitis B virus-related cryogobulinemic vasculitis. The role of antiviral nucleot(s)ide analogues: a review. J Intern Med. 2019;286:290-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2025;S0168-8278(25)00174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nityanand S, Holm G, Lefvert AK. Immune complex mediated vasculitis in hepatitis B and C infections and the effect of antiviral therapy. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;82:250-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang CR, Tsai HW. Human hepatitis viruses-associated cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:19-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Sausen DG, Shechter O, Bietsch W, Shi Z, Miller SM, Gallo ES, Dahari H, Borenstein R. Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Viruses: A Comprehensive Update with an Immunological Focus. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Rehermann B. Pathogenesis of chronic viral hepatitis: differential roles of T cells and NK cells. Nat Med. 2013;19:859-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kappus MR, Sterling RK. Extrahepatic manifestations of acute hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013;9:123-126. [PubMed] |