INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumours in the gastrointestinal tract and are classified as borderline tumours with a significantly better prognosis than cancer[1]. GISTs typically originate from the muscularis propria or the muscularis mucosae, and they may protrude either into or out of the lumen. Biologically, GISTs exhibit expansive growth characteristics. The most common sites for GISTs include the stomach (50%-60%) and small intestine (20%-30%); colorectal GISTs account for only approximately 5%, and the incidence of GISTs in the oesophagus is even lower[2]. For localized, resectable GISTs, surgical removal is the preferred treatment modality[3-5]. Depending on the specific characteristics of the tumour, the surgical approach may involve endoscopic resection, open surgical resection, or laparoscopic resection[6]. Historically, open surgery has been the standard treatment for GISTs. However, with the advancement of minimally invasive techniques and the development of updated surgical instruments, laparoscopic surgery has become increasingly widespread. Robot surgery, an advanced iteration of laparoscopic surgery, is characterized by an enhanced minimally invasive approach and a comparable postoperative recovery profile[7]. In particular, in the context of rectal procedures, robotic surgery can offer significant advantages[8]. Nevertheless, the limited availability of robotic equipment and the high costs associated with this surgical technique currently result in its less frequent application. Compared with open surgery, laparoscopic surgery is minimally invasive, offering advantages such as improved intraoperative visibility, reduced blood loss, smaller postoperative incisions, less pain, and faster recovery[9]. Laparoscopic surgery for GISTs should adhere to the same principles as open surgery, namely, “non-contact and minimal manipulation.” For GISTs that are small in size and located in anatomically favourable sites, laparoscopic resection is feasible. However, owing to the fragile nature of GIST tissue, which makes it prone to rupture and bleeding, any rupture significantly increases the risk of abdominal implantation or haematogenous metastasis following surgery[10-12]. According to reports, the probability of intraoperative rupture for GISTs measuring less than 5 cm is approximately 1.8% to 2.7%. In contrast, for GISTs exceeding 5 cm in size, the probability increases to approximately 2.7% to 4.4%[13]. The appropriateness of laparoscopic surgery for larger GISTs or tumours located in challenging anatomical sites remains inconclusive. Nonetheless, recent updates to clinical guidelines have led to a gradual relaxation of the criteria for laparoscopic surgery. Retrospective studies and clinical experience from the author suggest that laparoscopic resection is both safe and feasible for select patients with large or anatomically complex GISTs, particularly in centres with significant surgical expertise[14,15]. However, the above relevant research reports are retrospective studies, and large-sample prospective studies are lacking. Consequently, evidence-based medical data remain insufficient. The aim of this article is to review specific laparoscopic surgical strategies for GISTs based on their distinct anatomical locations.

OESOPHAGEAL GISTS

Oesophageal GISTs are relatively rare and most commonly occur in the lower oesophagus, followed by the middle and upper oesophagus. Surgery remains the primary treatment for oesophageal GISTs, with the approach (e.g., endoscopic resection, resection of the tumour and partial resection of the oesophagus) varying depending on tumour size. Endoscopic resection is a viable option for oesophageal GISTs with a tumour diameter of less than 2 cm and no high-risk factors, as assessed by endoscopic ultrasound. For tumours ranging in size from 2 to 6.5 cm, surgical resection is typically the first-line treatment. In cases where the tumour diameter exceeds 6.5 cm, a surgical approach that ensures complete tumour removal is needed. Depending on the specific tumour characteristics, either local excision or partial OE may be performed. According to a retrospective study conducted by Duffaud et al[16], seven patients with oesophageal GISTs demonstrated favourable surgical outcomes following preoperative treatment with imatinib aimed at reducing tumour size. Consequently, for larger oesophageal GISTs, particularly those located at the oesophagogastric junction, preoperative neoadjuvant targeted therapy can significantly enhance surgical outcomes and minimize the extent of surgical intervention.

GASTRIC GISTS

Laparoscopic treatment for gastric GISTs has become well established, with various retrospective studies confirming its safety and feasibility[17-19]. Laparoscopic approaches for treating gastric GISTs include extraluminal gastrectomy, intraluminal gastrectomy, and structural gastrectomy. Laparoscopic extraluminal gastrectomy typically involves wedge-shaped resection, which can be performed in two ways: (1) Creating a direct incision with a linear stapler, followed by suturing; or (2) Incising the stomach wall to remove the tumour, followed by suturing. The former approach is generally used for extrinsic GISTs and is relatively straightforward, but it requires the removal of some normal gastric tissue, making it unsuitable for tumours near the cardia or pylorus. The latter technique, applied to intracavitary GISTs, allows resection under direct vision, helping to preserve normal gastric tissue around the tumour and better protect the function of the cardia or pylorus. However, the disadvantage is that the gastric cavity is opened during the procedure, which increases the risk of tumour seeding and abdominal contamination. Laparoscopic endogastrectomy includes two variations: Laparoscopic transgastric parietal endogastrectomy and laparoscopic transparietal gastrectomy. In laparoscopic transparietal gastrectomy, a surgical pathway is established by incising the anterior gastric wall, preserving more of the normal gastric tissue, particularly when the GIST is located on the posterior wall or near the cardia. According to a previous report, twelve consecutive patients with gastric GISTs located 3 cm or less from the oesophagogastric junction underwent laparoscopic transgastric resection[20]. The mean operation time was 125 ± 25 minutes, the mean blood loss was 53 ± 32 mL, and the mean postoperative length of hospital stay was 5.1 ± 1.2 days. There was no tumour recurrence or evidence of stenosis of the EGJ during a mean follow-up of 15.3 ± 9.6 months. This technique avoids opening the mucosa, thus reducing the risk of contamination from gastric fluids; however, it is not suitable for invasive gastric GISTs and requires advanced laparoscopic skills. Additionally, the lack of a closed space during the procedure limits the effectiveness of vaporization, and tumour resection is typically performed via a linear cutting and stapling device after separating the gastric wall layers. Laparoscopic gastrectomy is associated with several benefits, including a lower risk of postoperative gastric stricture or torsion, while preserving the shape and function of the stomach[21-27]. Laparoscopic structural gastrectomy, including total gastrectomy, proximal gastrectomy, and distal gastrectomy, is typically used when partial resection of the GIST near the cardia or pylorus leads to significant functional impairment. However, structural gastrectomy often results in functional loss at the resected site and complications related to digestive tract reconstruction. To mitigate these issues, when possible, laparoscopic partial gastrectomy with pyloric preservation or laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with double-channel anastomosis and double-muscle flap anastomosis should be considered to support functional and anti-reflux digestive tract reconstruction. Function-preserving gastrectomy, which involves the retention of a portion of gastric tissue along with its neural innervation, not only effectively addresses the disease but also mitigates postoperative complications such as malnutrition and dumping syndrome. This approach consequently enhances the quality of life of patients; it is particularly well suited for the precise management of early-stage gastric cancer and benign lesions. Therefore, for gastric GISTs characterized by a substantial initial tumour volume, it is advisable to implement preoperative targeted therapy. Following a reduction in tumour size, function-preserving gastrectomy may be performed, which can increase the postoperative quality of life of patients. According to a retrospective study, in patients with locally advanced gastric GIST, preoperative short-term (≤ 8 months) use of imatinib is associated with higher recurrence-free survival (RFS) than long-term use[28]. Neoadjuvant imatinib allows stomach preservation in 96% of patients with excellent long-term RFS, even when treatment is started during an episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding[29].

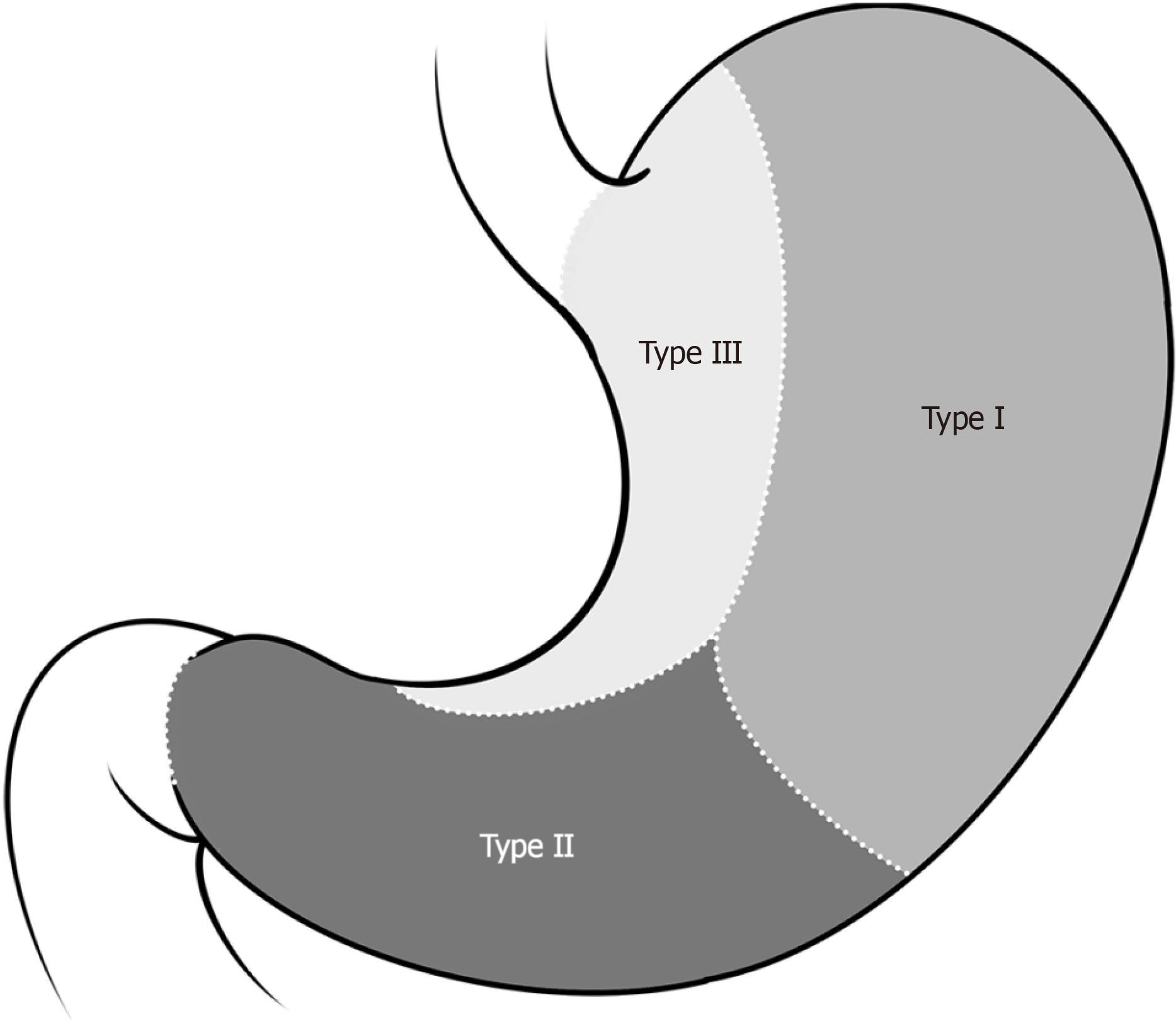

Laparoscopic surgical strategies for gastric GISTs vary depending on the location, size, and growth pattern of the tumour. According to Privette et al[30], gastric GISTs can be categorized into three types on the basis of their growth site: (1) Type I: Located in the greater curvature or fundus of the stomach; (2) Type II: Located in the gastric antrum or pylorus; and (3) Type III: Located at the oesophagogastric junction or lesser curvature of the stomach (Figure 1). For type I gastric GISTs, laparoscopic wedge-shaped resection via a linear cutter is typically performed. However, owing to the unique anatomical locations of type II and type III gastric GISTs, for particularly large or intracavitary tumours, wedge resection may lead to stenosis of the cardia or pylorus, causing postoperative difficulty or even an inability to eat. In such cases, laparoscopic endogastric resection is often necessary to avoid excessive gastric wall removal and prevent postoperative gastric stenosis. In some situations, structural resection may be needed.

Figure 1

Types of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumours.

With the increasing use of endoscopy and heightened public awareness of health issues, small gastric GISTs are being discovered more often during routine physical examinations. For patients with gastric GISTs < 2 cm, regular endoscopic monitoring and follow-up are generally recommended. However, for gastric GISTs ≥ 2 cm or those with high-risk features detected by endoscopic ultrasonography, as well as those that show rapid growth during follow-up, endoscopic or laparoscopic resection should be considered. In certain cases, simple endoscopic or laparoscopic resection may have limitations. The limitations of simple endoscopic resection are as follows: (1) Most gastric GISTs originate from the muscularis propria or submucosa, requiring deeper resection than do tumours originating from the mucosa. If the resection is not deep enough, it may be incomplete; if it is too deep, perforation may occur; (2) Endoscopic resection is particularly challenging for GISTs located in the fundus, cardia, or other difficult areas of the stomach, especially when they are relatively large; and (3) It is difficult to assess the depth of infiltration of gastric GISTs via endoscopy, which may result in a positive resection margin postoperatively. The main limitations of simple laparoscopic resection for gastric GISTs are as follows: (1) Due to the absence of tactile feedback in laparoscopic surgery, it can be challenging to locate small GISTs, especially those that are intracavitary or located on the posterior wall of the stomach; (2) Laparoscopic resection of gastric GISTs near the cardia or pylorus may lead to narrowing of the stomach cavity, potentially interfering with postoperative feeding; (3) The use of linear cutting staplers in laparoscopic surgery may result in the removal of excessive normal gastric tissue; and (4) For GISTs with unclear localization, the resection margin may be positive postoperatively, indicating incomplete removal of the tumour. In recent years, combined laparoscopic and endoscopic cooperative surgery (LECS) has emerged as a promising minimally invasive technique, capitalizing on the advantages of both approaches[31-33]. With the support of intraoperative endoscopy, laparoscopy not only facilitates accurate tumour localization and precise resection planning but also ensures negative resection margins and minimizes the excision of healthy gastric tissue. Additionally, this technique enables the timely detection and management of complications such as intracavitary bleeding, incomplete closure, and post-closure gastric stenosis. LECS improves safety and surgical outcomes by allowing endoscopic perforations caused inadvertently during endoscopic resection to be quickly identified and repaired under laparoscopic guidance. For endoscopic gastric GISTs, the tumour can be resected endoscopically first, followed by wound closure under laparoscopy, thus reducing the risk of complications compared with simple endoscopic resection[34]. For extraluminal gastric GISTs, the tumour can be localized via endoscopy and then resected via laparoscopy, with subsequent wound closure. During surgery, the endoscope can also assist in monitoring the morphology of the cardia to prevent postoperative strictures. LECS is particularly advantageous for gastric cardia and pyloric GISTs, as it effectively preserves the function of the cardia and pylorus, thereby avoiding the need for more invasive procedures such as total gastrectomy, proximal gastrectomy, or distal gastrectomy[35]. For GISTs located in the cardia, fundus folding is occasionally performed to prevent postoperative reflux disease resulting from intraoperative damage to the cardia structure[36]. A single-centre, retrospective study utilizing propensity score matching was conducted to compare the efficacy of LECS and endoscopic mucosal resection (ESD) in the treatment of GISTs[37]. The study revealed that 32 patients treated with LECS and 102 patients treated with ESD were balanced into 30 pairs. The rate of intraoperative complications was significantly lower in the LECS group than in the ESD group (P = 0.029). LECS patients had less intraoperative bleeding than ESD patients did [15.0 mL (range 9.5-50.0 mL) vs 43.5 mL (range 22.3-56.0 mL), P = 0.004]. The two groups had similar postoperative courses. There was no difference in the reoperation rate between the two groups (P = 0.112). Compared with the LECS group, the ESD group had a shorter operating time (41.5 minutes vs 96.5 minutes, P < 0.001). However, during a follow-up of 57.9 (± 28.9) months, the recurrence rate did not differ significantly between the two groups (0.0% vs 6.7%, respectively; P = 0.256). However, in traditional LECS, the open stomach cavity is directly connected to the abdominal cavity, which may lead to abdominal contamination or the potential spread of tumour cells. To address these concerns, several modified LECS techniques have been developed, including reverse LECS, closed LECS, non-exposed endoscopic gastric wall inversion, and non-exposed combined laparoscope-endoscopic tumour resection[32,38]. These advanced LECS methods are primarily used for gastric tumour resection but have also been applied for tumours in other areas of the digestive tract, such as the duodenum, colon, and rectum. Despite these improvements, modified LECS techniques still have limitations. For example, non-exposed endoscopic gastric wall inversion is technically challenging and time-consuming and demands high expertise from the endoscopist. Both non-exposure combined laparoscope-endoscopic tumour resection and non-exposed endoscopic gastric wall inversion are not suitable for treating gastric cardia GISTs[39]. Therefore, treatment strategies for gastric GISTs should remain individualized, with the choice of surgical approach determined by the surgeon’s experience and the tumour’s characteristics.

DUODENAL GISTS

Duodenal GISTs are rare and typically occur in the lower portion of the duodenum. The laparoscopic treatment strategy for duodenal GISTs depends on the size and location of the tumour and its relationship with surrounding organs. Given the complex anatomical relationships around the duodenum, the surgical approach should be tailored to the specific growth pattern of the tumour. Laparoscopic procedures for duodenal GISTs include segmental duodenectomy, duodenal wedge-shaped resection, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and duodenectomy with preservation of the pancreatic head[40]. For small duodenal GISTs that do not invade the pancreas or duodenal papilla, laparoscopic segmental or wedge-shaped duodenectomy is preferred. Tumours located along the mesenteric margin or the anterior wall of the duodenum are more likely to undergo segmental or wedge-shaped resection, as these areas are more amenable to localized excision. Although segmental or wedge-shaped resection of a duodenal GIST is relatively straightforward, the unique anatomical characteristics of the duodenum present challenges, and complications such as pancreatitis, pancreatic fistulas, and anastomotic stenosis may arise postoperatively. These potential complications require the surgeon’s close attention. Like gastric GISTs, duodenal GISTs can benefit from LECS (laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery) to minimize the extent of duodenal wall resection while ensuring safety at the resection margin. In the LECS approach for treating duodenal GISTs, the procedure begins with endoscopic excision of the tumour’s mucosal margin, followed by laparoscopic excision of the duodenal wall under endoscopic guidance. After the tumour is removed laparoscopically, the wound is sutured, and endoscopic examination is performed to check for bleeding, stenosis, or leakage. In more complex cases where local resection of tumours in the descending or horizontal parts of the duodenum is not feasible, pancreaticoduodenectomy is indicated; this is typically required when the tumour invades the duodenal papilla, the head of the pancreas, or the ampulla of Vater. If the tumour’s resection margin is less than 1 cm from the duodenal papilla, there is a risk of damage to the common bile duct or pancreatic duct during local resection, necessitating a more extensive surgical approach. However, if the head of the pancreas is intact, a duodenectomy with preservation of the pancreatic head may be considered. A study by Chok et al[41] comparing the outcomes of patients with duodenal GISTs who underwent local resection versus those who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy revealed that patients in the latter group had a higher rate of postoperative complications but no significant oncologic advantage. Another study retrospectively analysed 23 patients who underwent local resection and 10 patients who underwent laparoscopic or robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Patients who underwent local resection had a shorter operative time (280 vs 388.5 minutes, P = 0.004) and estimated blood loss (100 vs 450 mL, P < 0.001) and lower morbidity of postoperative complications (52.2% vs 100%, P = 0.013) than did those who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy[42]. Based on these findings, preoperative targeted therapy is recommended for this group of patients. Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, can reduce the stage and size of most GISTs before surgery, thereby narrowing the scope of the operation. This can help avoid unnecessary combined organ resections, reduce the risk of intraoperative bleeding and tumour rupture, and ultimately improve patient prognosis. However, a previous report indicated that there is no significant difference in postoperative survival rates between local duodenal resection and pancreaticoduodenectomy[43]. Further research may be necessary in the future to validate these findings.

SMALL INTESTINAL GISTS

Laparoscopic surgery for small intestinal GISTs can be categorized into two main approaches: Complete laparoscopic resection and laparoscopically assisted resection of small intestinal segments. The primary difference between these two methods lies in whether resection and reconstruction of the small intestine occur in vivo or in vitro. Since the removal of small intestinal tumours typically requires an auxiliary incision, laparoscopically assisted resection has become the more commonly used surgical approach. In this technique, the tumour is first accurately located under laparoscopic guidance. An auxiliary abdominal incision is then made, with the size of the incision determined by the tumour’s size. The segment of the small intestine containing the tumour is then exteriorized, allowing for resection and reconstruction outside the body. Compared with complete laparoscopic resection and reconstruction, the in vitro approach of laparoscopically assisted surgery tends to be faster, with a lower risk of tumour rupture and intraoperative bleeding. Similarly, for small intestine GISTs with a larger initial volume, preoperative targeted therapy may also be implemented prior to surgical intervention[44].

COLORECTAL GISTS

Colonic GISTs are rare, and lymph node metastasis is uncommon. As a result, laparoscopic segmentectomy is typically sufficient for treatment rather than complete mesocolectomy. Although rare, rectal GISTs are more commonly found in the middle and lower rectum. The anatomy of the rectum, particularly in the pelvic cavity, is complex, with the middle and lower rectum being in close proximity to several important organs, nerves, and blood vessels. Therefore, surgical intervention for rectal GISTs must consider not only the complete resection of the tumour but also the protection of functional structures. Function-preserving rectal resection maintains normal defecation function by safeguarding the anal sphincter and its nerve supply. This approach avoids the need for a permanent stoma, mitigates the risk of postoperative defecation disorders and sexual dysfunction, and enhances the overall quality of life of patients. Upon the clinical discovery of a rectal GIST, a range of diagnostic tests, including endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography, enhanced CT, and enhanced MRI, should be conducted to assess the characteristics of the tumour comprehensively. These include the tumour’s size, location, depth of invasion, circumferential margins, and relationship with neighbouring organs, as well as potential regional lymph node metastasis. The specific condition of the patient, the surgeon’s experience, and the available equipment must all be considered when selecting the most appropriate surgical approach. For small rectal GISTs, local resection is often sufficient. With the advancement of the transanal endoscopic microsurgery platform and transanal minimally invasive surgery, transanal resection has become the most commonly used method for the local resection of rectal GISTs. In some cases, GISTs located higher in the rectum can also be resected endoscopically. Tumours in special locations, such as the anterior rectal wall in women, can be resected vaginally, whereas those in the lower posterior rectal wall can be accessed through the sacral route (Kraske operation) or the anal sphincter route (Mason operation). The Kraske operation is challenging because of the narrow and deep surgical field. Conversely, the Mason operation offers a shallower surgical site with a more direct and spacious approach. However, it is associated with postoperative complications, including wound infections, anal fistulas, and anal sphincter incontinence[45]. For large rectal GISTs with deep local invasion, standard radical surgical methods-such as total mesorectal excision, specific mesorectal excision, or transsphincteric resection-are still employed to ensure complete tumour resection. In cases where the tumour is located too close to the anal margin or where anal function is expected to be compromised after surgery, combined abdominoperineal resection (APR) or transanal combined APR with permanent colostomy may be necessary. Intersphincteric resection is appropriate for low rectal GISTs that involve only the anal sphincter. However, if the tumour involves the longitudinal rectum, external sphincter, or anal levator, APR or extralevator APR is needed. Although GISTs typically do not metastasize to the lymph nodes and are usually amenable to R0 resection, radical surgery in line with rectal cancer protocols is not always needed. From an oncological standpoint, low rectal surgery may involve the risk of damaging autonomic nerves, potentially leading to postoperative complications such as defecation disorders, urinary and reproductive dysfunction, and even loss of anal function. However, from a surgical perspective, following the principle of “membrane anatomy”[46], which involves careful dissection along the anatomical spaces around the rectum, helps reduce blood loss and protects adjacent structures such as the ureters and nerves. With the increasing use of targeted therapies such as imatinib, preoperative neoadjuvant therapy has become an important tool, as it can shrink the tumour, localize its stage, increase the R0 resection rate, and increase the potential for anal preservation[47,48]; this, in turn, improves both the oncological prognosis and the postoperative quality of life of patients with GISTs. According to research conducted by Yang et al[49], the perioperative administration of imatinib and R0 resection were found to be associated with improved RFS in high-risk patients diagnosed with complete response GISTs. In contrast, among patients with rectal GIST, R1 resection was linked to a poorer RFS, regardless of whether they received perioperative imatinib treatment. However, a study conducted by Chinese scholars indicated that patients who received neoadjuvant treatment had superior 2-year RFS outcomes than those who did not, although the difference was not significant (91.7% vs 78.9%, P = 0.203). There were no significant differences in the 2-year OS rates (95.2% vs 91.3%, P = 0.441)[50]. Further studies are warranted to validate the long-term prognostic benefit for patients with rectal GISTs receiving neoadjuvant imatinib therapy.

Therefore, for rectal GISTs, especially those located in the lower rectum, a careful balance must be achieved between functional preservation and radical resection. In cases of small rectal GISTs where R0 resection can be achieved, local resection is a feasible option. However, in cases of rectal GISTs where R0 resection is difficult to achieve or where surgery would impair rectal or anal function, preoperative targeted therapy can help shrink the tumour and enable local resection with functional preservation, thus achieving both oncological control and functional preservation. Radical resection remains necessary in cases where preoperative targeted therapy is not an option or when there is no significant response to such therapy. In such cases, the primary goal of surgery is curative treatment, not anal preservation.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the effective management of GISTs hinges on strict adherence to surgical principles. It is essential to select an appropriate minimally invasive surgical approach tailored to the specific anatomical location, size, and other characteristics of the tumour, as well as to consider the complexity of resection. Based on the results of the ACOSOG Z9001 trial, imatinib therapy is safe and improves RFS for patients with GISTs[37]. Therefore, for surgeries involving combined organ resection or potential functional impairment, preoperative targeted therapy should be considered, or the operation should be approached with caution to maximize patient benefits.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C, Grade D

Novelty: Grade C, Grade D

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade C, Grade D

P-Reviewer: Rasa HK; Sun M S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ