Published online May 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i14.102791

Revised: December 20, 2024

Accepted: January 7, 2025

Published online: May 16, 2025

Processing time: 78 Days and 15.4 Hours

There has been a rise in the number of cases diagnosed as lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), caused by the transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis, specifi

A 38-year-old male presenting with symptoms of rectal bleeding, mucoid dis

LGV proctosigmoiditis is a crucial differential diagnosis in high risk patients, such as MSM that should be differentiated from IBD. Obtaining a thorough sexual history is pivotal to prevent misdiagnosis and guarantee prompt, effective therapy.

Core Tip: Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) should be considered as one of the differential diagnosis when confronting a patient with rectal symptoms to avoid misdiagnosis and needless treatments. Differentiating between LGV and inflammatory bowel disease can be challenging due to their similarity in clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological features especially in patients whom sexual history is not known. Our case illustrates the importance of sexual history in our diagnostic approach and the urge for clinicians to increase awareness of LGV among high risk populations.

- Citation: Khoury KM, Jradi A, Karam K, Fiani E. Lymphogranuloma venereum proctosigmoiditis misdiagnosed as inflammatory bowel disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(14): 102791

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i14/102791.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i14.102791

Chlamydia trachomatis is a gram-negative bacterium with 15 different serotypes that can be categorized based on their resulting infection: Trachoma, anogenital infection, and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). LGV is sexually transmitted disease mostly by oral or anal sex due to the contraction of serotypes L1, L2, and L3 of this bacterium with a rising number of cases in homosexual males who engage in sexual activity[1,2]. Moreover, there has been an evident link between patients diagnosed with LGV and a positive history of human immunodeficiency virus[3]. Diagnosing a patient with LGV can be challenging due to the unpredictable and varied nature of clinical symptoms[1]. Its most common presentations consisting of rectal pain, hematochezia, tenesmus, or mucous discharge can closely mimic those of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), similarly for the severe inflammatory changes found in rectal biopsy results contributing to the struggle in forming differential diagnosis[2,4,5]. The latter hence marks the importance of detailed and wholesome collection of the patient’s history to aid physicians in giving greater consideration to LGV as a differential diagnosis. For this, we herein depict the case of a 38 years old male patient who was diagnosed with LGV after revisiting the patient’s sexual history.

This is the case of an unmarried 38-year-old male, previously healthy, presenting to the Emergency Department with complaint of rectal bleeding, mucoid purulent discharge, and intermittent tenesmus for a duration of 4 weeks.

Upon further questioning, the patient mentioned associating symptoms of abdominal pain in the lower quadrants, periodic anal pain and tender lymphadenopathy with draining lymph nodes, while negating any symptoms of diarrhea, fever, or weight loss. History goes back to one month prior to presentation, when the early manifestations of his condition depicted progressively worsening anal discomfort followed by hematochezia with significant mucoid discharge two weeks later.

The patient’s previous history is negative for any gastrointestinal related issues prior to this episode. In regards to social history, the patient has not traveled recently, and does not indulge in alcohol, drugs, or smoking.

There was no family history of gastrointestinal disorders. The patient was febrile with a temperature of 39.5 °C. There was no discussion during the first evaluation about the patient’s sexual history and activity as neither side thought it was directly related to his symptoms.

Upon physical examination, the patient exhibited a noticeable tenderness at the level of the abdomen and pain in both lower quadrants without any rebound or guarding. Moving on to the perianal area, there were no significant findings showing to be negative for external hemorrhoids and anal fissures. Similarly concerning the rectum, digital rectal exam was negative for palpable tumors, but positive for pain and a significant amount of mucoid discharge.

The patient’s blood workup revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin = 12.5 g/dL), mild increase in white blood cell count (11500/mm³), and a minor elevation in C-reactive protein (25 mg/L).

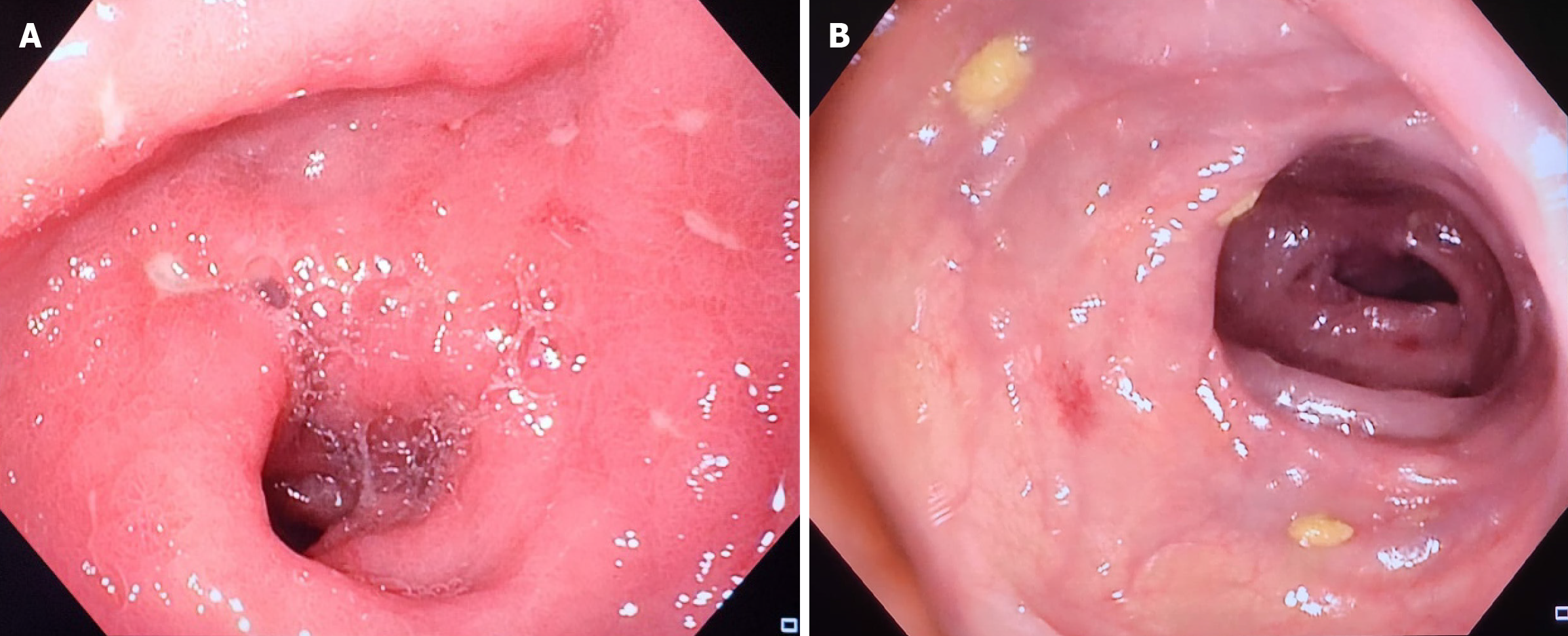

The latter results were inconclusive and led us to move on to endoscopy to continue investigations regarding the patient’s symptoms, whereby sigmoidoscopy revealed the presence of mucosal edema with coalescing nodules and ulcerations, primarily affecting the rectum and sigmoid colon (Figure 1) causing suspicion for IBD, specifically ulcerative colitis (UC). Therefore, biopsies were taken revealing severe inflammatory changes, granulomas, dysplasia and crypt distortion which are in conformity with characteristics seen in IBD.

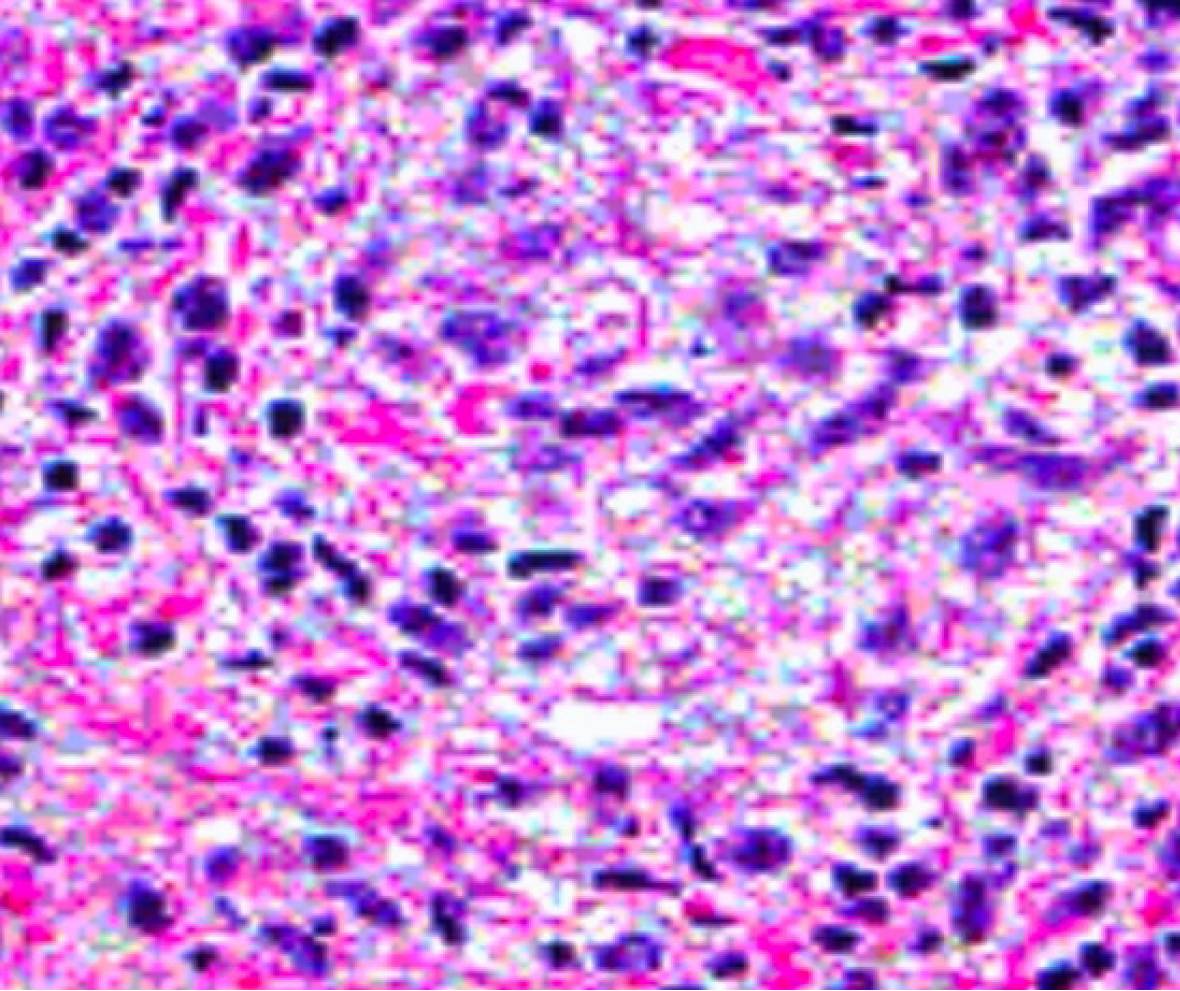

In aim to cover all bases and conduct a thorough investigation, a rectal swab followed by nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) was performed to test for sexually transmitted diseases, yielding a positive result for Chlamydia trachomatis (serotypes L1, L2, or L3), in addition to serology showing an increased concentration of Chlamydia-specific immunoglobulins with an IgA level of 25 U/mL and an IgG level of 40 U/mL (normal ranges < 10 U/mL). Hematoxyline and eosin staining revealed a dense inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histicoytes and neutrophils (Figure 2).

The aforementioned results with the patient’s clinical picture are in accordance with the diagnosis of LGV proctosigmoiditis. After thorough investigation and obtaining these results, the patient was questioned directly regarding his sexual history whereby he gradually confessed to his engagement in receptive anal intercourse with different male partners in the previous months. He failed to do so earlier due to his prior belief of irrelevance.

A full course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 21 days.

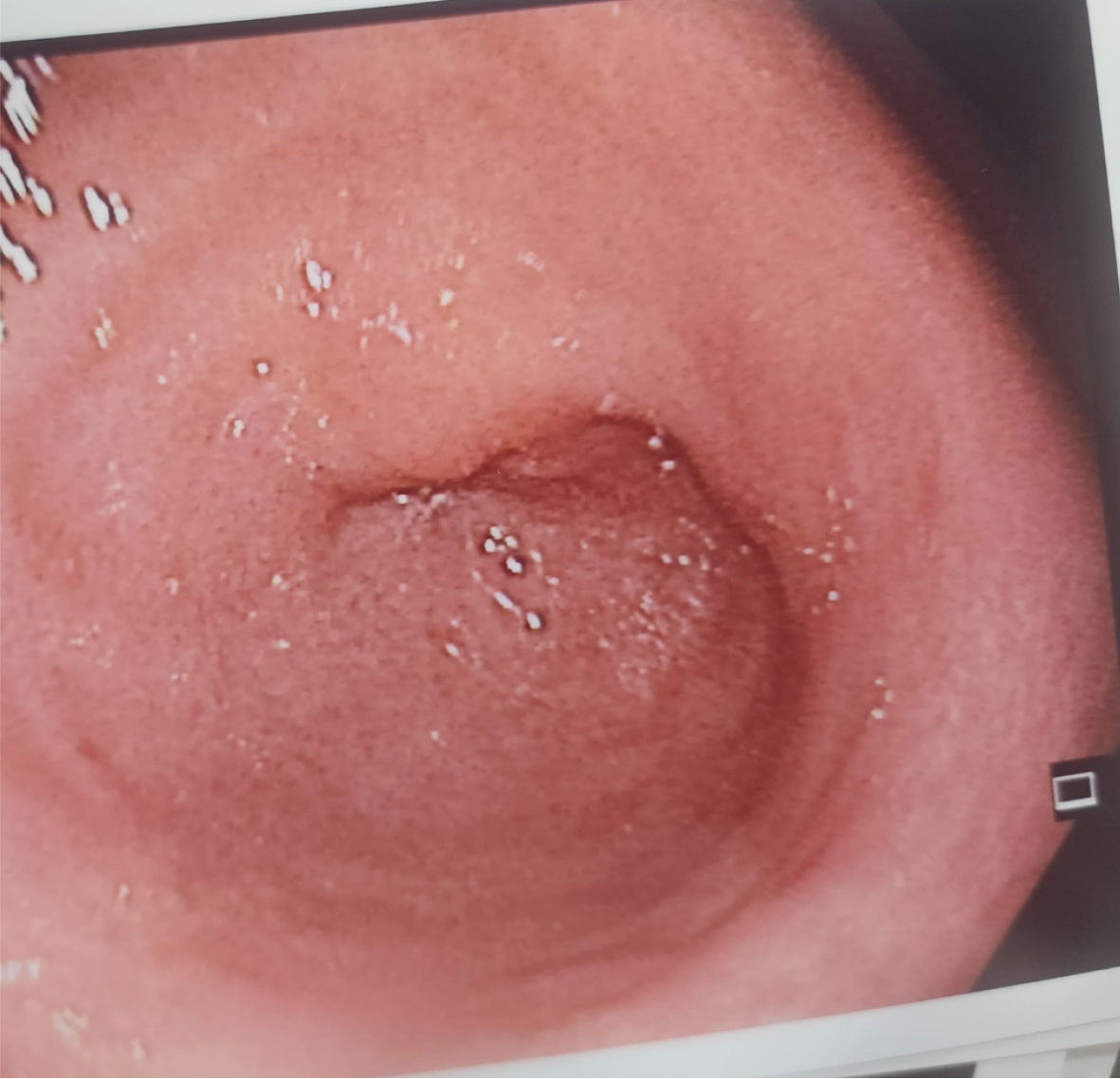

A follow-up colonoscopy was performed after the patient was treated with a full course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 21 days which revealed normal colonic mucosa at the level of the rectosigmoid junction (Figure 3). Biopsies taken from the rectosigmoid area came back negative, corroborating a complete resolution of LGV proctosigmoiditis.

Chlamydia Trachomatis serotypes L1, L2, and L3 are considered to be the primary cause of LGV. LGV primarily involves the lymphatic tissue and is considered to be more aggressive than other serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis that are associated with urogenital infections. This illness is common in men who have sex with men (MSM). Clinical symptoms are dependent on the stage of infection, with proctosigmoiditis being the sign of a later stage[4]. Gastrointestinal symptoms can make the diagnosis more challenging due to the similarity in features between LGV and IBD[4]. The clinical and endoscopic similarities between them put a significant burden on clinicians in differentiating among them, leading to delays and inappropriate treatment.

LGV can correspond to similar clinical manifestations as IBD, such as rectal discomfort, hematochezia, tenesmus (the sensation of incomplete evacuation), purulent or mucous discharge. LGV with proctosigmoiditis symptoms are indi

Colonoscopy is a crucial tool in diagnosing a patient with rectal symptoms, but findings can be confusing in terms of diagnosis and differentiation between LGV and IBD. LGV proctosigmoiditis shows mucosal ulcerations and inflammation, especially in the rectum and sigmoid colon which can mimic the findings seen in UC and Crohn’s disease[4]. In addition, the vague histopathological characteristics of LGV makes it more challenging to differentiate from IBD[6]. In cases where histopathological findings are inconclusive, immunohistochemical staining for Chlamydia trachomatis can assist in diagnosing the infection. In our case, sigmoidoscopy showed the presence of mucosal edema with coalescing nodules and ulcerations. Moreover, the initial biopsy showed a persistent inflammatory response, granulomas, dysplasia and crypt distortion; nevertheless, additional immunohistochemical testing like NAAT and rectal swab, which are considered the gold standard for diagnosing LGV, identified chlamydia (serotypes L1, L2, or L3) as the causative agent[6]. In addition, Chlamydia-specific immunoglobulins showed increased levels of IgA and IgG confirming the diagnosis of LGV proctosigmoiditis.

When approaching such symptoms, LGV proctosigmoiditis must be kept in mind as one of the differential diagnosis. To correctly diagnose it, a detailed medical history of the patient is required, particularly in individuals who have risk factors like MSM. The gold standard for diagnosing LGV is NAAT for chlamydia trachomatis[7]. Another differential diagnosis that can be confusing while diagnosing LGV is rectal lymphoma due to its similar colonoscopic findings[8].

According to the current European and United states sexually transmitted diseases guidelines, treatment for LGV follows a 21-day course of doxycycline 100 mg BID. This can cure the infection and prevents complications such as strictures and fistulas[9]. Azithromycin can be used instead in cases where doxycycline can’t be used. Additionally, any patient who is diagnosed with LGV should be tested for other sexually transmitted diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, gonorrhea. In our case, the patient was prescribed 100 mg of doxycycline twice a day for 21 days which greatly improved his symptoms—discharge and pain of the rectum-within 1 week of treatment, and was educated on the importance of safety and protection during sexual activities.

LGV should be considered as one of the differential diagnosis when confronting a patient with rectal symptoms to avoid misdiagnosis and needless treatments. Differentiating between LGV and IBD can be challenging due to their similarity in clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological features especially in patients whom sexual history is not known. Our case illustrates the importance of sexual history in our diagnostic approach and the urge for clinicians to increase awareness of LGV among high risk populations.

| 1. | O'Byrne P, MacPherson P, DeLaplante S, Metz G, Bourgault A. Approach to lymphogranuloma venereum. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62:554-558. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rawla P, Thandra KC, Limaiem F. Lymphogranuloma Venereum. 2023 Jul 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Rönn MM, Ward H. The association between lymphogranuloma venereum and HIV among men who have sex with men: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gallegos M, Bradly D, Jakate S, Keshavarzian A. Lymphogranuloma venereum proctosigmoiditis is a mimicker of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3317-3321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:235-241. [PubMed] |

| 6. | He X, Madhav S, Hutchinson L, Meng X, Fischer A, Dresser K, Yang M. Prevalence of Chlamydia infection detected by immunohistochemistry in patients with anorectal ulcer and granulation tissue. Hum Pathol. 2024;144:8-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tsomidis I, Kouroumalis E. Chlamydia trachomatis: An unusual cause of rectosigmoiditis. J Clin Images Med Case Rep. 2024;5:3072. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Sullivan B, Glaab J, Gupta RT, Wood R, Leiman DA. Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) proctocolitis mimicking rectal lymphoma. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13:1119-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pimentel R, Correia C, Estorninho J, Gravito-Soares E, Gravito-Soares M, Figueiredo P. Lymphogranuloma Venereum-Associated Proctitis Mimicking a Malignant Rectal Neoplasia: Searching for Diagnosis. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2022;29:267-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |