Published online Mar 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i8.1523

Peer-review started: December 16, 2023

First decision: January 10, 2024

Revised: January 19, 2024

Accepted: February 22, 2024

Article in press: February 22, 2024

Published online: March 16, 2024

Processing time: 86 Days and 17.2 Hours

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) is a rare skin tumor that mainly affects the elderly population. Tumors often present with slow growth and a good prognosis. EPCs are usually distinguished from other skin tumors using histopathology and immunohistochemistry. However, surgical management alone may be inadequate if the tumor has metastasized. However, currently, surgical resection is the most commonly used treatment modality.

A seventy-four-year-old woman presented with a slow-growing nodule in her left temporal area, with no obvious itching or pain, for more than four months. Histopathological examination showed small columnar and short spindle-shaped cells; thus, basal cell carcinoma was suspected. However, immunohistochemical analysis revealed the expression of cytokeratin 5/6, p63 protein, p16 protein, and Ki-67 antigen (40%), and EPC was taken into consideration. The skin biopsy was repeated, and hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed ductal differentiation in some cells. Finally, the patient was diagnosed with EPC, and Mohs micrographic surgery was performed. We adapted follow-up visits in a year and not found any recurrence of nodules.

This case report emphasizes the diagnosis and differentiation of EPC.

Core Tip: Eccrine porocarcinomas (EPCs) are rare skin tumors that grow slowly with no obvious discomfort. They are difficult to distinguish from basal cell carcinomas, particularly those that occur on the face. Histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry are necessary to diagnose atypical lesions, their importance is demonstrated in our case. Multiple biopsies at different times are necessary to visualize ductal differentiation in cells. Our case reported a brief period of EPC in the temporal region of an elderly woman. We hope that our case findings will help in better understanding of EPCs.

- Citation: Wu ZW, Zhu WJ, Huang S, Tan Q, You C, Hu DG, Li LN. Eccrine porocarcinoma in the tempus of an elderly woman: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(8): 1523-1529

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i8/1523.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i8.1523

The skin is the largest organ in the human body, and its tissue structure is complex. Skin tumors can be identified through the actions of various pathogenic factors. The diversity of skin tumors makes their diagnoses difficult. Here, we report a case of eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) of the tempus in an elderly woman. EPC is a rare skin tumor which originates from sweat glands. It has the high misdiagnosis rate due to the rarity of the disease and the atypicality of the site of occurrence[1,2]. Our case described the diagnostic methods of EPC from the histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry, and detailed explanation of the current treatment methods for EPC.

A nodule on the left tempus, which was growing for more than four months.

A soybean-sized papule had developed on the left tempus of a seventy-four-year-old woman, four months prior to pre

The patient had no history of tumor and immune disease.

Similar symptoms were not reported in her family.

An approximately 1.5 cm × 2 cm nodule was observed on the left tempus of the patient’s face. The nodule had a rough surface and an irregular boundary (Figure 1). A black suture line was present at the center of the lesion. No intumescent lymph nodes were palpable in the neck.

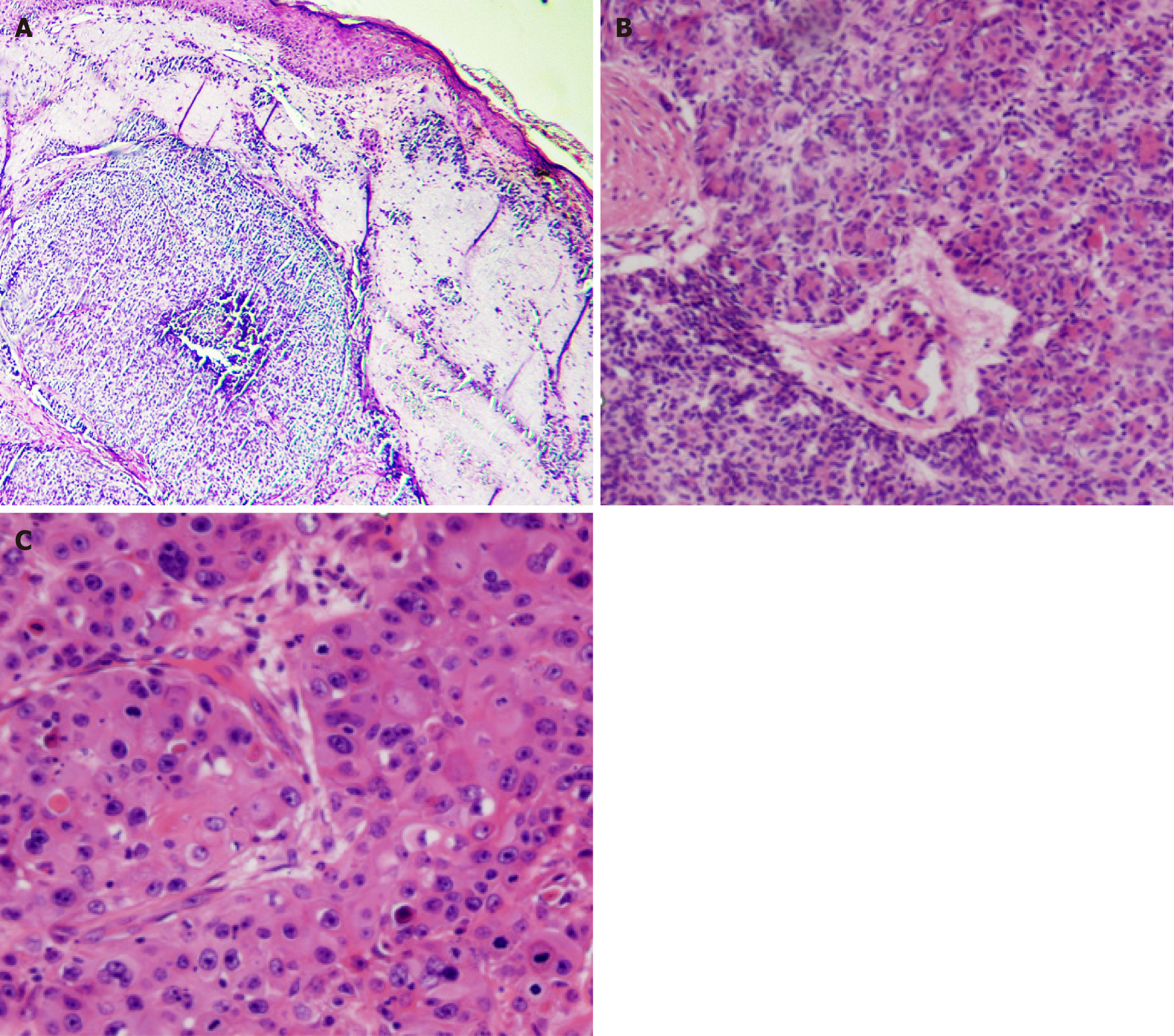

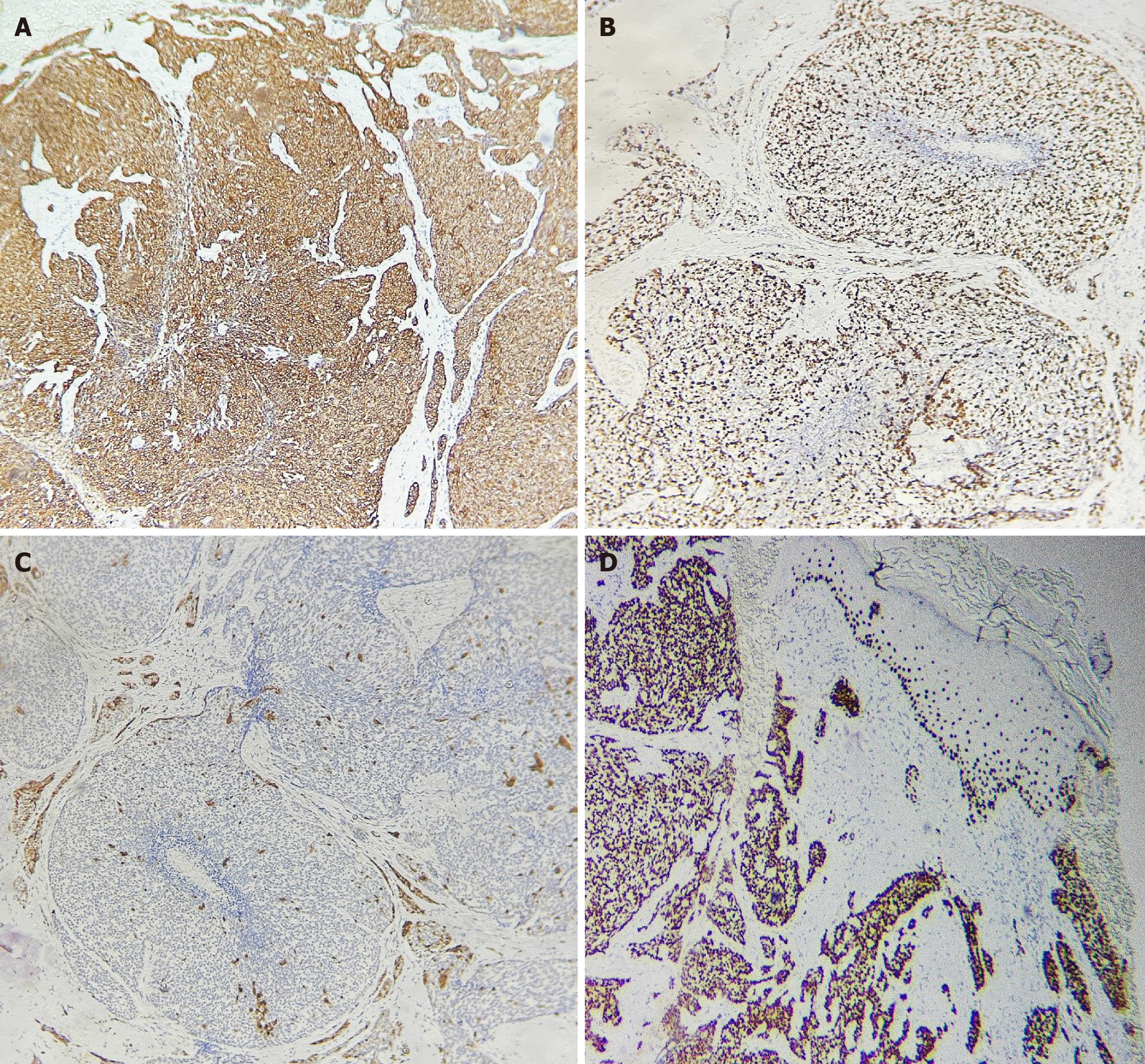

Skin biopsy was performed. The first histopathological examination revealed small columnar and short spindle-shaped cells (Figure 2A). The later one revealed part of the cells appearing to be ductally differentiated. It can be seen many pore structures (Figure 2B). Some tumor cells have large and hyperchromatic nuclei, and it can be seen lots of apoptotic bodies (Figure 2C). Immunohistochemistry revealed the expression of cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, p63 protein (p63), p16 protein (p16), and Ki-67 antigen (40%) (Figure 3). Blood biochemistry showed no significant abnormalities.

The computed tomography of the skull, and ultrasound of superficial lymph glands showed no remarkable findings.

The presence of ductal differentiation in cells ruled out basal cell carcinoma. The small cell size, ductal differentiation, and lumen formation excluded squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Combined with clinical manifestations and pathological findings, EPC was diagnosed.

After obtaining informed consent from the patient, Mohs micrographic surgery was performed (Figure 4).

No recurrence of nodules was noted during the follow-up visits in the next year.

EPC is a rare pernicious tumor originating from the sweat glands of the skin. It was first reported by Pinkus and Mehregan[3]. Studies have shown that from 2000 to 2018, the incidence of EPC in the United States was 0.045 per 100000 individuals[4]; with the improvement of diagnostic technology, the diagnostic rate of EPC has also increased annually. Furthermore, the elderly population is at a higher risk of EPCs. However, there have been reports of young women with EPC whose conditions progressed significantly during pregnancy[5]. No significant sex differences have been noted for this disease[6]. The most common location of presentation is the head and neck (39.9%), followed by the lower extremities (33.9%)[6]. Similar to our case, EPC has been reported in the left temporal area, with the appearance of a verrucous lesion[7]. However, the tumors had a longer growth time (one year to twenty years)[7] than that in our case (four months). What makes it special is that the EPC in our case seemed growing more quickly than the reported ones[7], which needs more study to clarify it. EPCs usually appear as hard, purple or red nodular plaques with smooth warty or ulcerated surfaces[8,9], and are often associated with a malignant transformation that occurs over a previous poroma originating from the intraepidermal components of the sweat glands[10]. The pathogenesis of EPC is complex and varied, and includes benign tumor transformation, sun exposure, and immunosuppression[11]. In the present case, the patient was an elderly woman living in a rural area, who was exposed to ultraviolet radiation.

Currently, surgical resection is the most commonly accepted treatment option for EPC especially the Mohs micro

Currently, there is no clear diagnostic protocol for EPCs. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemistry have a high diagnostic value for EPCs. HE staining of EPC tissue sections reveals irregular tumors consisting of characteristic porous basal-like cells, with part of the cells appearing to be ductally differentiated at the least, in addition to the characteristics of typical tumor cells. The presence of a tumor duct is necessary for the diagnosis of EPC[9,10]. Additionally, immunochemical markers play a significant role in the diagnosis. One study investigated whether the immunohistochemical expression of p53 protein, retinoblastoma protein, and p16 could differentiate EPCs from poromas and found that six EPC cases (43%) showed an abnormal expression of p16[15]. The strong expression of p63 and CK5/6 were detected in EPCs and p63 could distinguish EPCs from metastatic adenocarcinomas[16,17]. EPCs often need to be distinguished from basal cell carcinomas, which consist of morphologically basaloid cells with scant cytoplasm, elongated hyperchromatic nuclei, intercellular bridges, and peripheral cells that are not fence-like[18]. Compared to SCCs, EPCs have a small cell size, ductal differentiation, and lumen formation. The expression of engrailed homeobox 1 and CK19 were found to be able to improve the accuracy of histologic diagnosis of EPC, and these two markers are independent that distinguish EPCs from SCCs[2]. Furthermore, the express of mast/stem cell growth factor receptor also become a more and more crucial role to make a distinction between EPCs and SCCs[19]. EPC is also often misdiagnosed as amelanotic melanoma, granuloma, telangiectasia, or fibroma[20]. Additionally, we need to summarize more EPC cases in this area of skin to summarize the clinical characteristics of the disease better. We also need to follow up for a longer time period to evaluate the recurrence.

EPC is a rare skin tumor that grows slowly and is heterogeneous and nonspecific. EPCs in the temporal area are even rarer. Owing to its similar clinical presentation with those of SCC and basal cell carcinoma, its differential diagnosis is warranted. Diagnosis is often made through histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry, and specific immunochemical markers still need to be studied to help distinguish EPCs from other skin tumors. Surgical resection is currently the most commonly used mode of treatment, especially Mohs micrographic surgery. We hope that this report will provide a better understanding of EPCs.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cassell III AK, Liberia; Sira AM, Egypt S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM

| 1. | Li YX, Gudi M, Yan Z. Primary Eccrine Porocarcinoma of the Breast: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2022;2022:4042298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Miura K, Akashi T, Namiki T, Hishima T, Bae Y, Sakurai U, Murano K, Shiraishi J, Warabi M, Tanizawa T, Tanaka M, Bhunchet E, Kumagai J, Ayabe S, Sekiya T, Ando N, Shintaku H, Kinowaki Y, Tomii S, Kirimura S, Kayamori K, Yamamoto K, Ito T, Eishi Y. Engrailed Homeobox 1 and Cytokeratin 19 Are Independent Diagnostic Markers of Eccrine Porocarcinoma and Distinguish It From Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:499-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. Epidermotropic errccrine carcinoma. A case combining features of errccrine poroma and Paget's dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:597-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gibbs DC, Yeung H, Blalock TW. Incidence and trends of cutaneous adnexal tumors in the United States in 2000-2018: A population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:226-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jeon SP, Kang SJ, Jung SJ. Rapidly growing eccrine porocarcinoma of the face in a pregnant woman. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:715-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Baba HO, Salih RQ, Hawbash MR, Mohammed SH, Othman S, Saeed YA, Habibullah IJ, Muhialdeen AS, Nawroly RO, Hammood ZD, Abdulkarim NH. Porocarcinoma; presentation and management, a meta-analysis of 453 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;20:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mulinari-Brenner FA, Mukai MM, Bastos CA, Filho EA, Santamaria JR, Neto JF. [Eccrine porocarcinoma: report of four cases and literature review]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:519-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Meriläinen AS, Pukkala E, Böhling T, Koljonen V. Malignant Eccrine Porocarcinoma in Finland During 2007 to 2017. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, Kim B, Seed PT, McKee PH, Calonje E. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Puttonen M, Isola J, Ylinen O, Böhling T, Koljonen V, Sihto H. UV-induced local immunosuppression in the tumour microenvironment of eccrine porocarcinoma and poroma. Sci Rep. 2022;12:5529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wittenberg GP, Robertson DB, Solomon AR, Washington CV. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: A report of five cases. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:911-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tidwell WJ, Mayer JE, Malone J, Schadt C, Brown T. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1078-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Godillot C, Boulinguez S, Riffaud L, Sibaud V, Chira C, Tournier E, Paul C, Meyer N. Complete response of a metastatic porocarcinoma treated with paclitaxel, cetuximab and radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2018;90:142-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zahn J, Chan MP, Wang G, Patel RM, Andea AA, Bresler SC, Harms PW. Altered Rb, p16, and p53 expression is specific for porocarcinoma relative to poroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:659-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qureshi HS, Ormsby AH, Lee MW, Zarbo RJ, Ma CK. The diagnostic utility of p63, CK5/6, CK 7, and CK 20 in distinguishing primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic carcinomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:145-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, Calonje E, Lyle S, Diwan AH, Lazar AJ. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:474-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Grimme H, Petres A, Bergen E, Wiemers S, Schöpf E, Vanscheidt W. Metastasizing porocarcinoma of the head with lethal outcome. Dermatology. 1999;198:298-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Joshy J, Mistry K, Levell NJ, van Bodegraven B, Vernon S, Rajan N, Craig P, Venables ZC. Porocarcinoma: a review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1030-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:306-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |