Published online Aug 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i22.5245

Revised: June 11, 2024

Accepted: June 24, 2024

Published online: August 6, 2024

Processing time: 77 Days and 15.8 Hours

Gout and seronegative rheumatoid arthritis (SNRA) are two distinct inflammatory joint diseases whose co-occurrence is relatively infrequently reported. Limited information is available regarding the clinical management and prognosis of these combined diseases.

A 57-year-old woman with a 20-year history of joint swelling, tenderness, and morning stiffness who was negative for rheumatoid factor and had a normal uric acid level was diagnosed with SNRA. The initial regimen of methotrexate, leflunomide, and celecoxib alleviated her symptoms, except for those associated with the knee. After symptom recurrence after medication cessation, her regimen was updated to include iguratimod, methotrexate, methylprednisolone, and folic acid, but her knee issues persisted. Minimally invasive needle-knife scope therapy revealed proliferating pannus and needle-shaped crystals in the knee, indicating coexistent SNRA and atypical knee gout. After postarthroscopic surgery to remove the synovium and urate crystals, and following a tailored regimen of methotrexate, leflunomide, celecoxib, benzbromarone, and allopurinol, her knee symptoms were significantly alleviated with no recurrence observed over a period of more than one year, indicating successful management of both conditions.

This study reports the case of a patient concurrently afflicted with atypical gout of the knee and SNRA and underscores the significance of minimally invasive joint techniques as effective diagnostic and therapeutic tools in the field of rheumatology and immunology.

Core Tip: Addressing the rare co-occurrence of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis and atypical knee gout, this case reinforces the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges inherent in rheumatology. This highlights the necessity for clinicians to maintain a high degree of suspicion for atypical disease presentations and the importance of personalized, innovative treatment strategies. The successful outcome in this case, achieved through a combination of minimally invasive diagnostic techniques and a customized treatment plan, provides valuable insights for the effective management of similar complex cases.

- Citation: Chen ZY, Ou-Yang MH, Li SW, Ou R, Chen ZH, Wei S. Concomitant atypical knee gout and seronegative rheumatoid arthritis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(22): 5245-5252

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i22/5245.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i22.5245

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, progressive autoimmune disorder characterized by symmetric polyarthritis, leading to joint pain, swelling, and significant morbidity due to morning stiffness and limited joint function[1]. With a global prevalence estimated between 0.24% and 1.00%[2], RA poses diagnostic challenges, especially in its seronegative form, which does not present rheumatoid factor (RF). This absence can lead to the misclassification or nondetection of RA in approximately 15% to 25% of cases[3]. Concurrently, gout, a common metabolic derangement resulting from uric acid dysregulation, typically manifests with monosodium urate crystal deposition in single joints, often the first metatarsophalangeal joint; however, atypical presentations, such as bilateral knee involvement and the presence of normal levels of uric acid during flares, are also documented[4]. The co-occurrence of RA and gout is infrequent due to disparate autoimmune and inflammatory pathways and divergent etiological triggers. Moreover, the intersection of the seronegative RA (SNRA) with atypical knee gout represents a clinical rarity, with scant literature reporting such complex cases. This case report describes the intricate diagnostic process and therapeutic strategy for a patient with concurrent atypical knee gout and SNRA who underwent minimally invasive joint interventions. Our findings underscore the necessity for heightened clinical vigilance and tailored therapeutic approaches for managing such multifaceted rheumatologic conditions.

A 57-year-old female patient presented with recurrent swelling and tenderness across multiple joints, accompanied by exacerbated bilateral knee pain and swelling over the previous week.

Approximately 20 years prior, the patient began experiencing swelling and pain in the palms of her hands, proximal interphalangeal joints, and both wrists without any apparent triggers. The morning stiffness lasted for more than 30 minutes but improved with activity. Despite systemic treatment, the knees continued to exhibit recurrent swelling, tenderness, and joint effusion, rendering the patient unable to walk unassisted. Consequently, the patient was admitted to our hospital in a wheelchair for surgical debridement to address joint swelling and effusion.

Six months prior, laboratory tests revealed normal serum uric acid levels, an RF of 9.19 IU/mL (negative), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies (negative), a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 3.1 mg/L (within the normal range of less than 10 mg/L), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 7.0 mm/hour (within the normal range of less than 20.0 mm/hour). According to the 2010 classification criteria and scoring system revised by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the patient scored 6 points, leading to a diagnosis of SNRA treatment that included oral methotrexate (10.0 mg once weekly), leflunomide (10.0 mg daily), celecoxib (0.2 mg daily), and folic acid (10.0 mg once weekly). The patient’s symptoms significantly improved after several days but then recurred after cessation of treatment, impacting activities such as squatting. The treatment regimen was subsequently adjusted to include a combination of iguratimod, methotrexate, methylprednisolone, and folic acid. After more than three months of this adjusted treatment, the patient still experienced discomfort in her knee joints.

The patient was postmenopausal. She denied any family history of similar disease outbreaks.

The patient presented with warm, tender, swollen soft tissues around both knee joints, with significantly restricted active and passive range of motion. The patellar tap test was positive. There were no signs of photosensitivity, recurrent oral ulcers, Raynaud's phenomenon, jaundice, rash, fever, chest tightness, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Her heart rate and respiratory rate were normal, and no abnormal cardiac or pulmonary sounds were detected. Her abdomen was soft without tenderness, no palpable masses were noted, and her liver and spleen were not palpable.

Upon admission, the patient's serum uric acid level was 336 μmol/L, within the normal range (155-357 μmol/L). All the following tests were negative: RF, anti-keratin antibodies, anti-CCP antibodies, double-stranded DNA antibodies, anti-mitochondrial antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, ribosomal P protein, histones, nucleosomes, anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen antibodies, centromere protein B, nRNP/SM, and human leukocyte antigen B27. The anti-streptolysin "O" test was normal. Positive findings included Jo-1 antibodies, elevated CRP at 69.8 mg/L (normal range < 10 mg/L), and an increased ESR at 65.0 mm/hour (normal range < 20.0 mm/hour). Routine blood, urine, stool, and tumor marker tests revealed no significant abnormalities.

The patient did not undergo any imaging studies as part of the diagnostic evaluation.

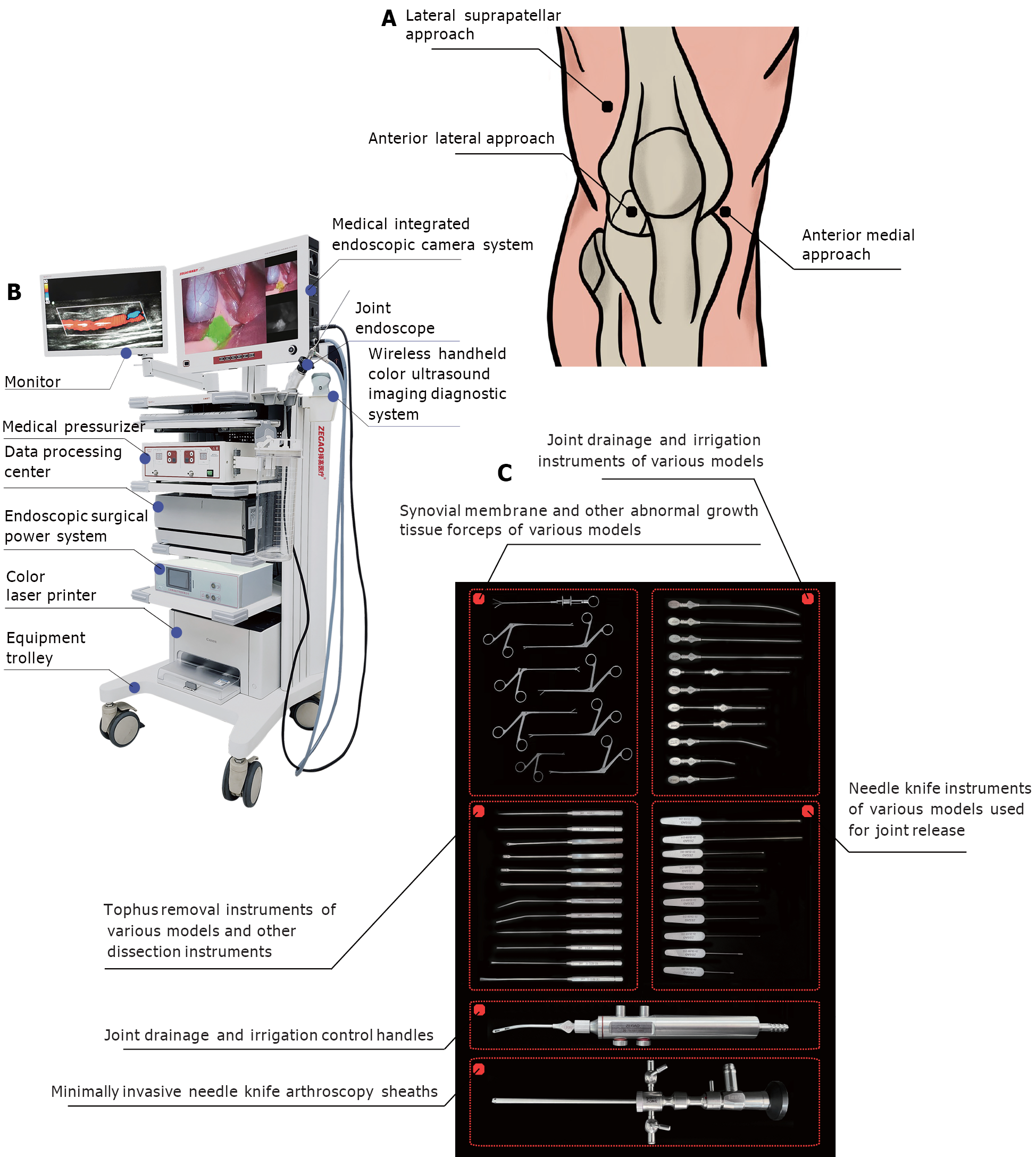

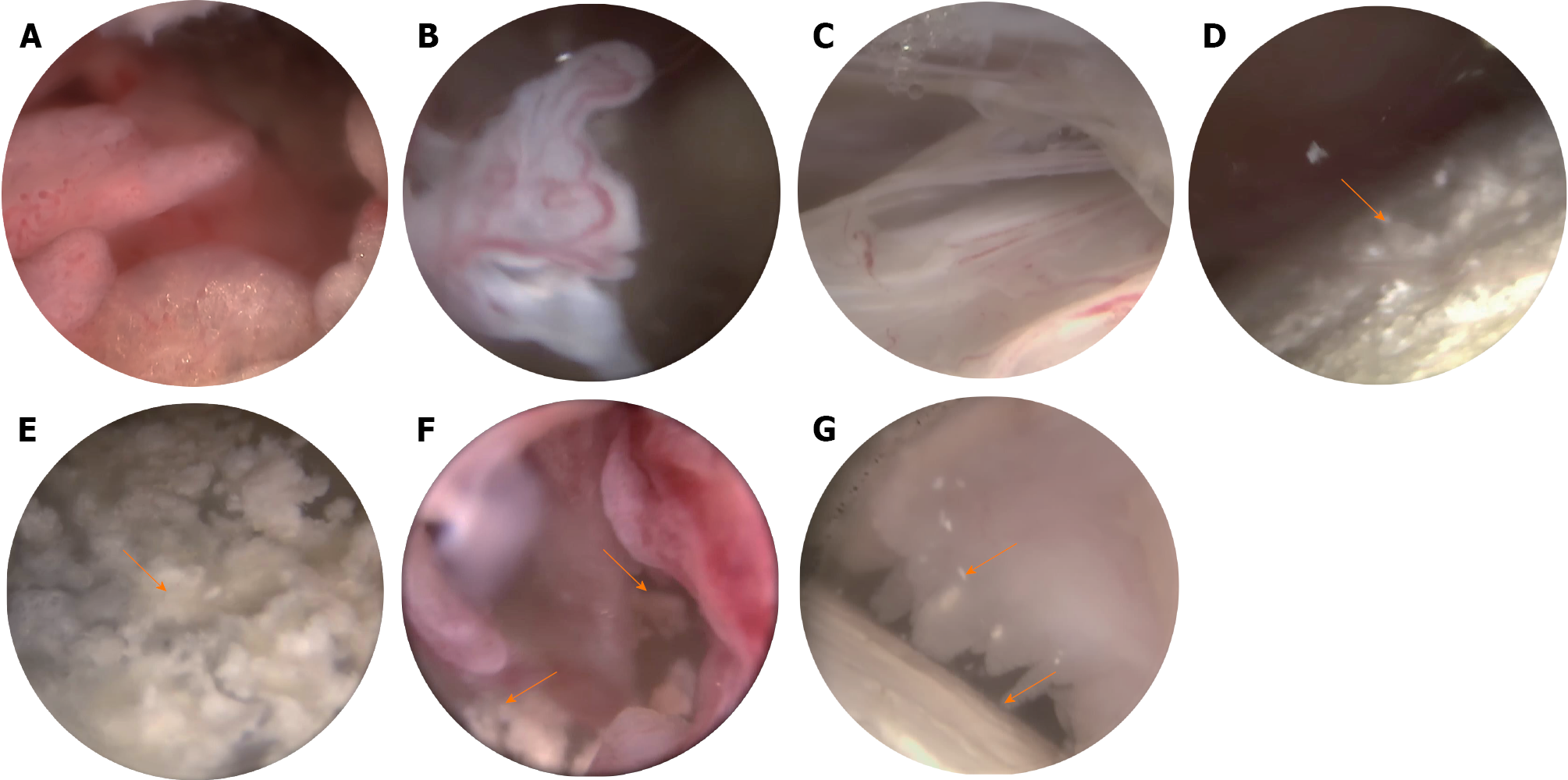

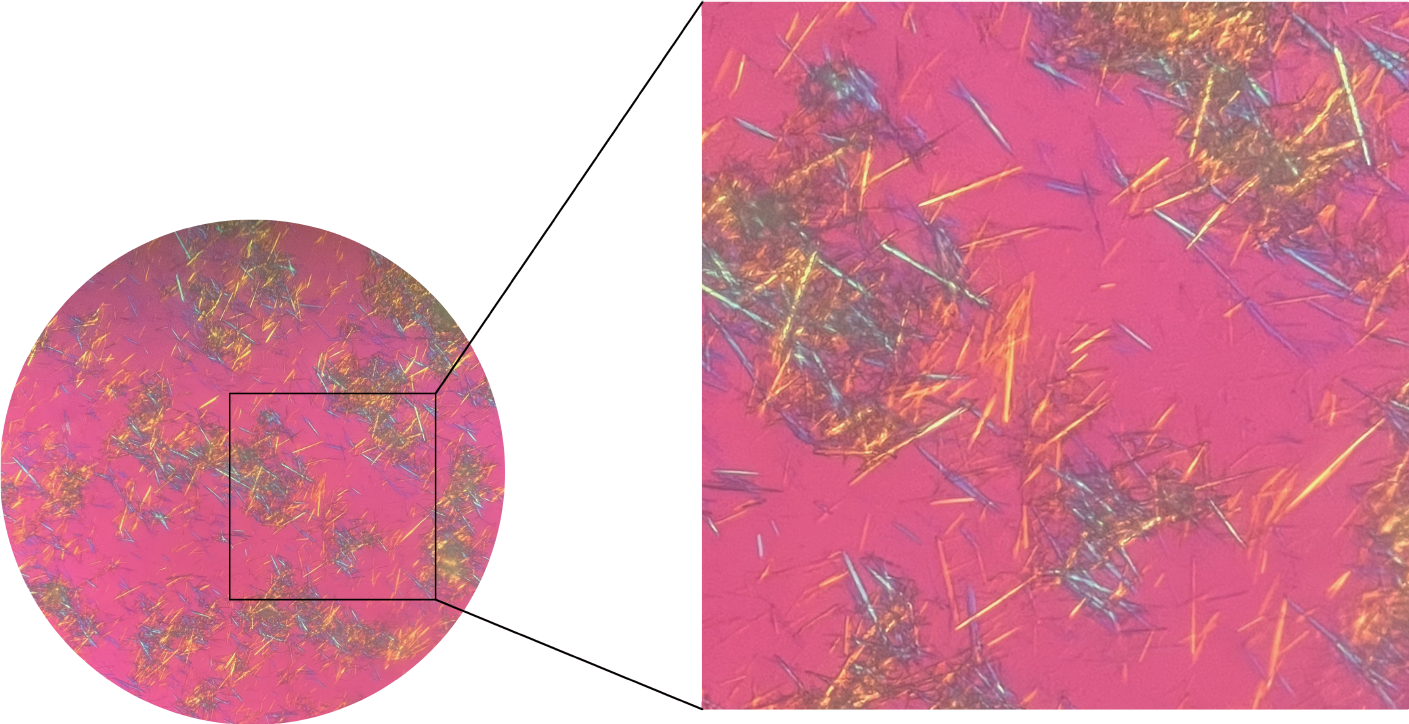

To further clarify the diagnosis, a minimally invasive needle-knife scope procedure was performed on the patient’s knee joints. This minimally invasive technique combines acupotomy with modern endoscopic technology to treat intra-articular lesions through tiny incisions under visual conditions. Various types of instruments, including release needles, irrigation needles, dissection needles, biopsy forceps, and curettes, are utilized to clear, dissect, irrigate, and medicate local pathological tissues. These tools are inherently more minimally invasive and are engineered for ease of use. It is a diagnostic and therapeutic technique that is well suited for rheumatologists. The surgical instruments and pathways are illustrated in Figure 1. The procedure involved adequate local anesthesia with lidocaine. An incision was made at a predetermined site, the subcutaneous fascia and muscle layers were dissected, and the joint capsule was opened to establish a surgical pathway. A needle arthroscope sheath was inserted, the core of the sheath was removed, and a minimally invasive needle-knife scope was introduced along with an irrigation fluid entry channel. Irrigation fluid was injected, and the areas examined included the suprapatellar pouch, patellofemoral joint space, medial tibial plateau, medial meniscus, medial recess, intercondylar notch, lateral tibial plateau, lateral meniscus, and lateral recess. During the surgery, cloudy synovial fluid was noted, with snowflake-like particles filling the field of view. Extensive vascularization of the cartilage and medial meniscus, with crawling over the cartilage surface toward the center, was consistent with the synovial presentation in SNRA patients. Additionally, scattered or clustered chalky white deposits were observed on the joint capsule, synovium, meniscus, and cartilage surfaces (Figure 2). These white materials were removed and fixed in ethanol, and further microscopic examination confirmed that they were urate crystals (Figure 3).

The patient was diagnosed with SNRA complicated by gout.

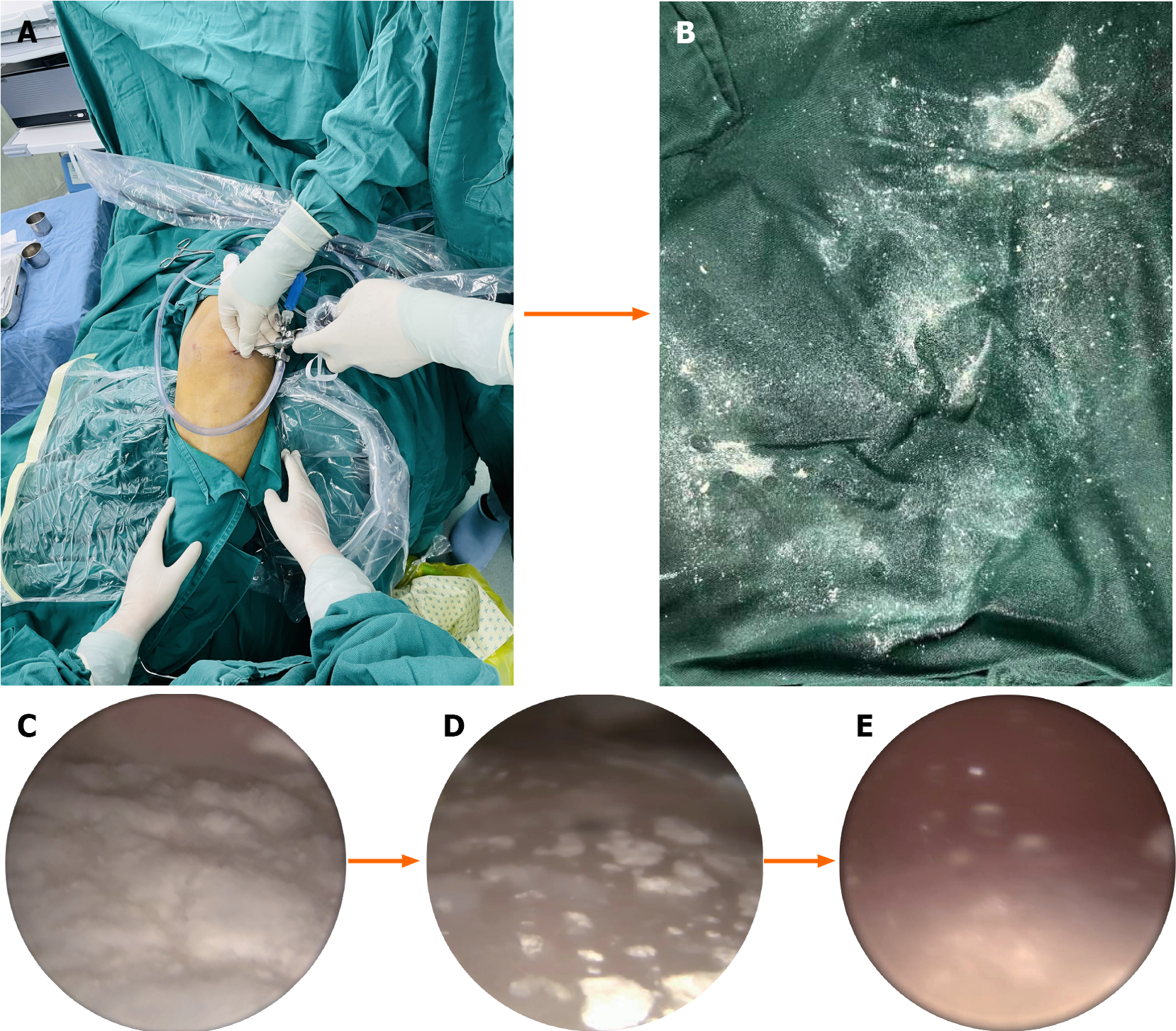

During the procedure, the adhesions were released, and the joint cavity was irrigated using a flushing solution introduced through the outflow channel of the minimally invasive needle-knife scope until the irrigant was clear. Subsequently, through a minimally invasive portal opposite or lateral to the initial entry, a scoop was inserted. Under needle arthroscopic guidance, gouty tophi and white, transparent urate crystals were gently removed from within the joint. Using the needle and a peeler, crystals adhering to the cartilage surface and synovial tissue were peeled off and removed. Extensive flushing with the irrigation solution was repeatedly performed to thoroughly clear the urate crystals. The process of removing urate crystals is illustrated in Figure 4. The operation concluded with suturing of the incision, which was then covered with sterile gauze and a compression bandage to stop any bleeding. Postoperatively, the patient was prescribed oral methotrexate (10.0 mg once weekly), leflunomide (10.0 mg daily), celecoxib (0.2 g daily), benzbromarone capsules (50.0 mg daily), allopurinol (0.1 g daily), and folic acid (10.0 mg once weekly).

One day after surgery, the patient experienced significant relief from knee joint pain and showed marked improvement in joint mobility, as she was able to get out of bed and walk independently. At a follow-up over a year later, the patient's knee joint symptoms were reported to have completely resolved, and there was no recurrence.

RA and gout both have notable prevalence rates, but instances of their co-occurrence are uncommon, with insufficient research exploring their relationship. Clinically, during the acute phase of atypical gout, the reliability of serum uric acid levels as a diagnostic marker is contentious, as these levels may not be elevated[5]. This could lead to an underrecognition of gout in patients presenting with polyarticular symptoms, especially when concurrently suffering from RA. Studies have shown that a significant portion of patients experiencing acute gout flare-ups have normal uric acid levels, implying that hyperuricemia is not a definitive indicator during acute attacks[6,7]. The infrequent merging of gout and RA may be attributed to several factors. First, the immunosuppressive nature of monosodium urate crystals could modulate the immune response characteristic of RA, diminishing the typical inflammatory processes associated with gout[8,9]. The presence of inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and autoantibodies such as RF in RA might also mitigate the manifestation of gout[10]. Moreover, during states of heightened inflammation, increased excretion of uric acid could result in serum uric acid levels within the normal range, obscuring the presence of gout[11]. The oxidative metabolism of uric acid to allantoin, especially in the absence of uricase, may also contribute to the atypical presentation of gout in RA patients[12]. The use of RA medications that impact purine metabolism, such as methotrexate and leflunomide, could suppress uric acid levels, potentially masking gout symptoms[13]. Furthermore, hormonal effects in females, particularly postmenopausal women, can lead to greater uric acid excretion, which complicates the interplay between gout and RA[9]. These nuances indicate a complex and poorly understood relationship between RA and gout, necessitating more rigorous diagnostic approaches when both diseases are suspected.

In this case report, the patient presented a complex scenario with concurrent gout and RA but without typical hyperuricemia or positive RF and anti-CCP antibodies at admission, complicating the initial diagnosis. Needle arthroscopy was pivotal in revealing significant vascular proliferation and urate deposits within the knee joint, alongside joint manifestations, ultimately confirming an atypical presentation of knee joint gout coexistent with the SNRA. Intriguingly, studies indicate that monosodium urate crystals are more commonly found in RA patients who test negative for serum RF and anti-CCP antibodies, with a prevalence of 70%, as opposed to only 10% in seropositive RA patients[5]. This may be due to the influence of monoclonal RF on the interaction between crystals and neutrophils; for example, monoclonal RF binding can inhibit neutrophil activation by IgG-coated crystals, leading to the accumulation of urate crystals in SNRA patients[14]. Despite being considered a less aggressive form of RA, emerging research suggests that SNRA may be associated with more intense inflammatory activity[15,16], as reflected in the ACR/EULAR classification criteria, which require a greater joint count for definitive SNRA diagnosis[17]. Compared with seropositive RA patients, SNRA patients often exhibit worse radiographic outcomes and more active disease at baseline[15,18]. In the acute inflammatory phase of SNRA, uric acid metabolism may be heightened, potentially leading to normal serum uric acid levels and complicating the diagnosis of gout, thereby increasing the risk of underdiagnosis.

Further research is essential to explore whether antibodies such as RF can inhibit the surface activity of monosodium urate crystals. However, this study also suggests that in RA patients who are seronegative and maintain normal blood uric acid levels, persistent joint symptoms despite rheumatic drug therapy warrant comprehensive joint examination using a minimally invasive needle-knife approach. This approach is critical for detecting monosodium urate crystals and assessing disease severity. Importantly, the majority of women with gout develop this condition after menopause, a factor that should be carefully considered in middle-aged and elderly female RA patients[19]. In this case, the patient's ability to mobilize independently the day after needle arthroscopic removal of intra-articular urate crystal deposits underscores the effectiveness of needle arthroscopic debridement in managing atypical gout attacks. Research supports minimally invasive treatment for alleviating knee joint pain, limited range of motion, and gait disturbances due to urate crystals, with such therapy resulting in favorable outcomes[20,21]. Moreover, combining minimally invasive treatment with urate-lowering drugs has been found to yield better results than pharmacotherapy alone[22]. A case report on arthroscopic debridement for knee gout showed sustained symptom relief without recurrence over a one-year follow-up, consistent with our observations[23]. In this study, the minimally invasive needle-knife scope combined needle knife therapy with arthroscopy, focusing primarily on the gentle clearing and irrigation of joints. Compared with traditional arthroscopy, the use of a blunt dissection approach involves minimal incisions, typically less than 0.5 cm, which results in reduced trauma and facilitates quicker recovery. This procedure is particularly designed for addressing stubborn joint and soft tissue swelling and pain in rheumatic conditions, enhancing efficacy while minimizing damage to existing tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and menisci. The use of imaging equipment allows for precise visual guidance, significantly lowering the risks associated with blind treatments and improving success rates. Moreover, when performed under local anesthesia, the minimally invasive needle-knife procedure eliminates the need for general or spinal anesthesia, thereby decreasing the risk of infection and enhancing cost-effectiveness. It requires fewer personnel, operates with lower logistical demands, and allows for simple, efficient procedures. Patients typically experience minimal postoperative side effects and bleeding, with recovery often occurring within 24 hours. This method offers a broad treatment scope with significant advantages in terms of safety and recovery speed. Nonetheless, the long-term efficacy of needle arthroscopic management in patients with intra-articular urate crystal deposition requires further study.

Gout and RA typically exhibit a negative correlation, and their concurrent manifestation is relatively rare. However, there seems to be a noteworthy link between atypical gout, often marked by normal blood uric acid levels and bilateral knee joint involvement, and SNRA. In such instances, the minimally invasive needle-knife technique has proven to be highly effective both in diagnosing and treating these complex clinical presentations. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the disease process and aids in the effective management of patients exhibiting symptoms of both conditions.

| 1. | Gravallese EM, Firestein GS. Rheumatoid Arthritis - Common Origins, Divergent Mechanisms. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:529-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 165.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Almutairi KB, Nossent JC, Preen DB, Keen HI, Inderjeeth CA. The Prevalence of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Population-based Studies. J Rheumatol. 2021;48:669-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | De Stefano L, D'Onofrio B, Gandolfo S, Bozzalla Cassione E, Mauro D, Manzo A, Ciccia F, Bugatti S. Seronegative rheumatoid arthritis: one year in review 2023. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023;41:554-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Patel UJ, Freetly TJ, Yueh J, Campbell C, Kelly MA. Chronic Tophaceous Gout Presenting as Bilateral Knee Masses in an Adult Patient: A Case Report. J Orthop Case Rep. 2019;9:16-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Petsch C, Araujo EG, Englbrecht M, Bayat S, Cavallaro A, Hueber AJ, Lell M, Schett G, Manger B, Rech J. Prevalence of monosodium urate deposits in a population of rheumatoid arthritis patients with hyperuricemia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schlesinger N, Norquist JM, Watson DJ. Serum urate during acute gout. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1287-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schlesinger N, Baker DG, Schumacher HR Jr. Serum urate during bouts of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:2265-2266. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Raman D, Abdalla AM, Newton DR, Haslock I. Coexistent rheumatoid arthritis and tophaceous gout: a case report. Ann Rheum Dis. 1981;40:427-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao G, Wang X, Fu P. Recognition of gout in rheumatoid arthritis: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e13540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Merdler-Rabinowicz R, Tiosano S, Comaneshter D, Cohen AD, Amital H. Comorbidity of gout and rheumatoid arthritis in a large population database. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:657-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang J, Sun W, Gao F, Lu J, Li K, Xu Y, Li Y, Li C, Chen Y. Changes of serum uric acid level during acute gout flare and related factors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1077059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zinellu A, Mangoni AA. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between Uric Acid and Allantoin and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Costa NT, Scavuzzi BM, Iriyoda TMV, Lozovoy MAB, Alfieri DF, de Medeiros FA, de Sá MC, Micheletti PL, Sekiguchi BA, Reiche EMV, Maes M, Simão ANC, Dichi I. Metabolic syndrome and the decreased levels of uric acid by leflunomide favor redox imbalance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Med. 2018;18:363-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gordon TP, Ahern MJ, Reid C, Roberts-Thomson PJ. Studies on the interaction of rheumatoid factor with monosodium urate crystals and case report of coexistent tophaceous gout and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44:384-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barra L, Pope JE, Orav JE, Boire G, Haraoui B, Hitchon C, Keystone EC, Thorne JC, Tin D, Bykerk VP; CATCH Investigators. Prognosis of seronegative patients in a large prospective cohort of patients with early inflammatory arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:2361-2369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Choi S, Lee KH. Clinical management of seronegative and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis: A comparative study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nordberg LB, Lillegraven S, Lie E, Aga AB, Olsen IC, Hammer HB, Uhlig T, Jonsson MK, van der Heijde D, Kvien TK, Haavardsholm EA; and the ARCTIC working group. Patients with seronegative RA have more inflammatory activity compared with patients with seropositive RA in an inception cohort of DMARD-naïve patients classified according to the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:341-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Geng Y, Zhou W, Zhang ZL. A comparative study on the diversity of clinical features between the sero-negative and sero-positive rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3897-3901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Eun Y, Kim IY, Han K, Lee KN, Lee DY, Shin DW, Kang S, Lee S, Cha HS, Koh EM, Lee J, Kim H. Association between female reproductive factors and gout: a nationwide population-based cohort study of 1 million postmenopausal women. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23:304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Steinmetz RG, Maxted M, Rowles D. Arthroscopic Management of Intra-articular Tophaceous Gout of the Knee: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Orthop Case Rep. 2018;8:86-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Aoki T, Tensho K, Shimodaira H, Akaoka Y, Takanashi S, Shimojo H, Saito N, Kato H. Intrameniscal Gouty Tophi in the Knee: A Case Report. JBJS Case Connect. 2015;5:e74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang X, Wanyan P, Wang JM, Tian JH, Hu L, Shen XP, Yang KH. A Randomized, Controlled Trial to Assess the Efficacy of Arthroscopic Debridement in Combination with Oral Medication Versus Oral Medication in Patients with Gouty Knee Arthritis. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:628-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kinoshita T, Hashimoto Y, Okano T, Nishida Y, Nakamura H. Arthroscopic debridement for gouty arthritis of the knee caused by anorexia nervosa: A case report. J Orthop Sci. 2023;28:286-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |