Published online Jul 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i20.4065

Revised: May 10, 2024

Accepted: May 17, 2024

Published online: July 16, 2024

Processing time: 83 Days and 16.2 Hours

The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) was introduced late in China and is primarily used for investigating and evaluating health problems in older adults in outpatient and community settings. However, there are few reports on its application in hospitalized patients, especially older patients with diabetes and hypertension.

To explore the nursing effect of CGA in hospitalized older patients with diabetes and hypertension.

We performed a retrospective single-center analysis of patients with comorbid diabetes mellitus and hypertension who were hospitalized and treated in the Jiangyin Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine between September 2020 and June 2022. Among the 80 patients included, 40 received CGA nursing interven

After 6 months, the nursing outcomes indicated that patients who underwent CGA nursing interventions experienced a significant decrease in blood glucose indicators, such as fasting blood glucose, 2-h postprandial blood glucose, and HbA1c, as well as blood pressure indicators, including DBP and SBP, compared with the control group (P < 0.05). Quality of life assessments, including physical health, emotion, physical function, overall health, and mental health, showed marked improvements compared to the control group (P < 0.05). In the study group, 38 patients adhered to the clinical treatment requirements, whereas only 32 in the control group adhered to the clinical treatment requirements. The probability of treatment adherence among patients receiving CGA nursing interventions was higher than that among patients receiving standard care (95% vs 80%, P < 0.05).

The CGA nursing intervention significantly improved glycemic control, blood pressure management, and quality of life in hospitalized older patients with diabetes and hypertension, compared to routine care.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective single-center study introduces the novel application of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) in older patients with diabetes and hypertension. Our findings demonstrate that CGA-based interventions significantly improve glycemic control, blood pressure, quality of life, and treatment adherence, offering a promising strategy for holistic care in this demographic.

- Citation: Bao DY, Wu LY, Cheng QY. Effect of a comprehensive geriatric assessment nursing intervention model on older patients with diabetes and hypertension. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(20): 4065-4073

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i20/4065.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i20.4065

With declining fertility rates and increased life expectancy, the global population is aging rapidly. China's seventh national census data show a sustained rise in the number of older adults over recent decades[1]. This demographic shift raises concerns about the health of older individuals. The combination of age-related frailty and chronic diseases increases the risk of adverse health outcomes in older adults[2]. Aging is typically associated with a decline in physical function and changes in dietary habits, resulting in an increasing prevalence of age-related diseases[3]. This issue is not limited to medicine and is increasingly becoming a financial burden on the healthcare economy[4]. Diabetes and hyper

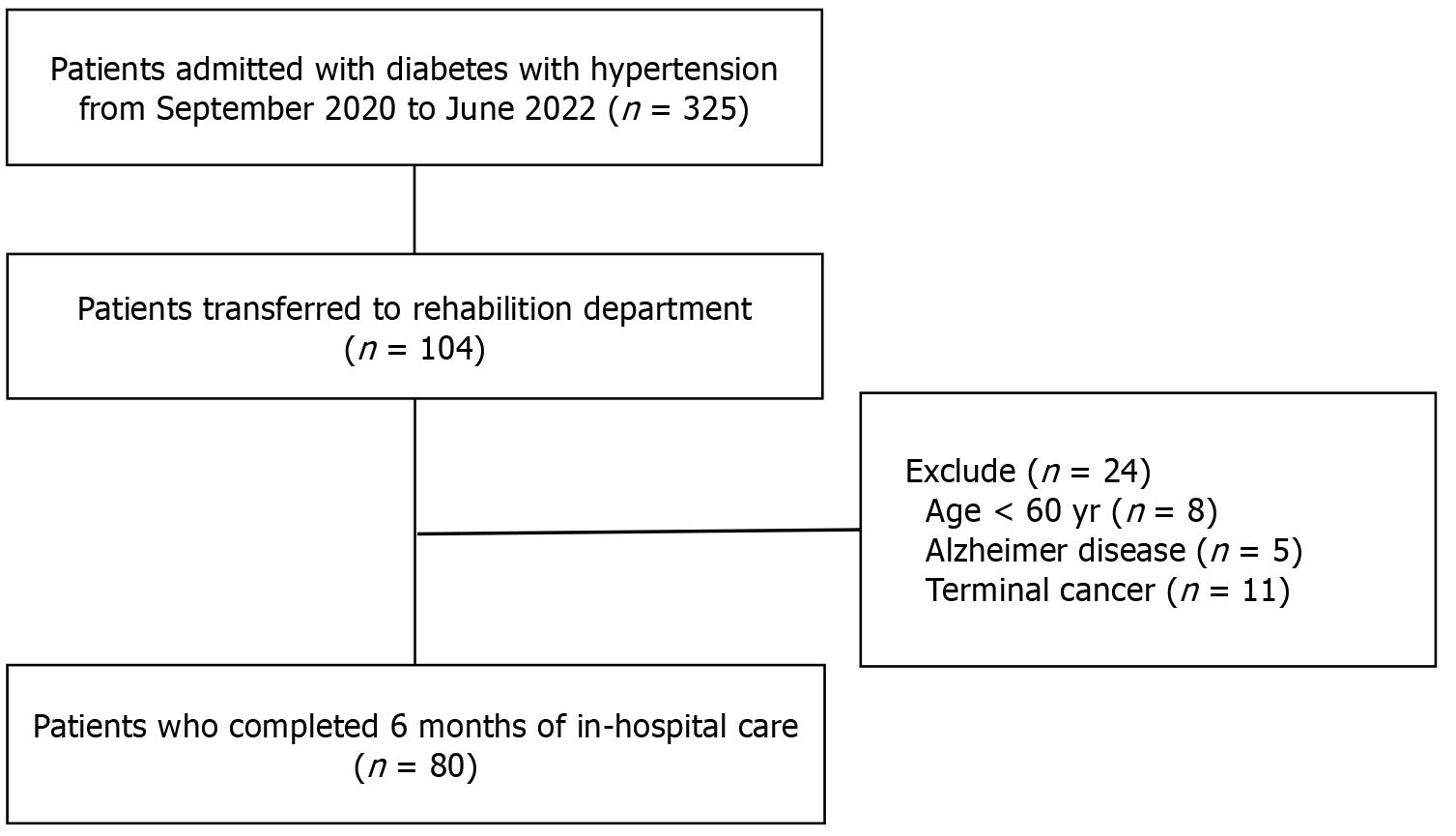

This single-centered, retrospective study investigated older patients with diabetes and hypertension who were hospitalized in the Jiangyin Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine between September 2020 and June 2022. Participants were aged ≥ 60 years, with diabetes and hypertension diagnosed according to the 2019 World Health Organization criteria. Older patients with severe communication disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, were excluded, as well as those critically ill who were long-term bedridden, including patients in intensive care units, those with advanced cancer, and unaccompanied patients. Finally, 80 patients were included in the study: 40 in the study group and 40 in the control group. Figure 1 illustrates the participation process in the study, detailing the number of patients deemed qualified, excluded, or enrolled.

After admission, the patients received routine nursing care, which included the collection of their general and medical histories. Moreover, routine care, such as fall prevention measures and regular patient monitoring, was provided.

Pre-preparation: A multidisciplinary CGA intervention team with extensive clinical experience was established, consisting of a head nurse (responsible for coordinating nursing interventions), four registered nurses (responsible for implementing specific nursing interventions), a clinical pharmacist (responsible for guiding rational drug use), a nutritionist (responsible for formulating a nutrition intervention plan), a psychological consultant (responsible for psychological nursing interventions of patients), and two chief physicians (responsible for supervising the entire nursing process and evaluating nursing results). A personal CGA profile was created to collect general patient information (e.g., sex, age, disease course), clinical data, and scale assessment results. This profile was used to collect dynamic information about a patient’s illness and set care goals. Before implementing the CGA evaluation, we trained team members, introduced the use of CGA profiles, and assigned responsibilities. Patients are required to complete the profile within two days of admission.

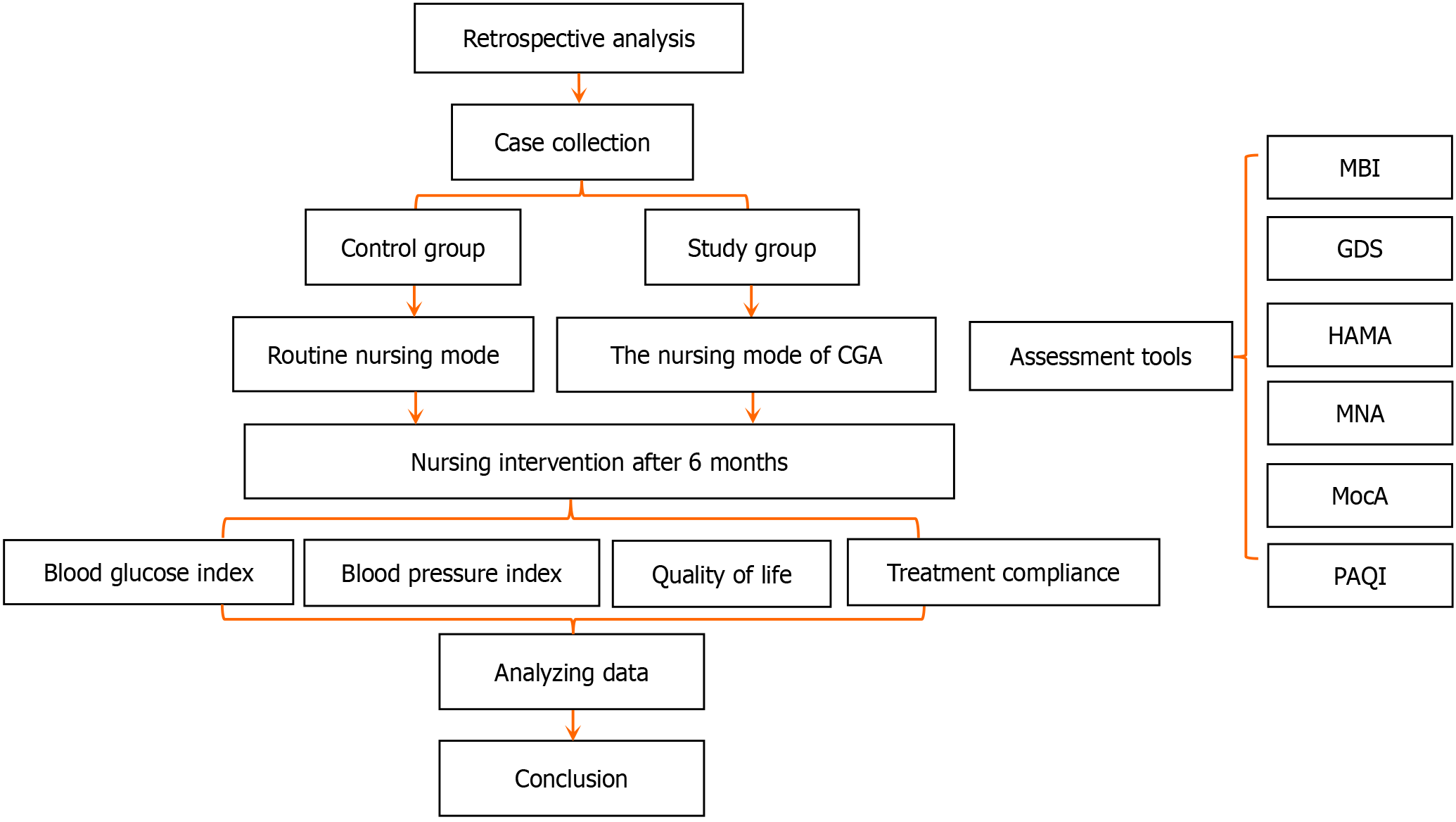

CGA: Multiple scales are used to evaluate patients' mental states, physical capabilities, nutritional status, cognitive function, and sleep quality, allowing for the identification of changes, analysis of causes, and development of appropriate interventions, including the Modified Barthel Index (MBI), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA), Mini Nutritional Assessment Scale (MNA), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). See Table 1[9-15].

| Scales | Objects | Criteria |

| MBI | Physical function | The total score was 100 points, with classifications as follows: 75–95 (mild dependence), 50–70 (moderate dependence), 25–45 (severe dependence), and 0–20 points (full dependence)[9,10] |

| GDS | Depression level | The total score was 30 points, indicating depressive symptoms if > 11 points were scored[11] |

| HAMA | Anxiety levels | The total score was 50 points, with classifications as follows: ≥ 29 (severe anxiety), 21–28 (marked anxiety), 14–20 (moderate anxiety), and 7–13 points (mild anxiety)[12] |

| MNA | Nutritional status | The total score was 30 points, with classifications as follows: > 24 (good), 17–24 (possible malnutrition), and < 17 points (malnutrition)[13] |

| MoCA | Cognitive function | The total score was 30 points, wherein < 26 points indicate cognitive impairment[14] |

| PSQI | Sleep quality | The total score was 21 points, with classifications as follows: 0–5 (good quality), 6–10 (general), 11–15 (poor), and 16–21 points (fairly poor)[15] |

Nursing intervention: Monitoring of blood glucose and blood pressure, hierarchical patient management, and the implementation of individualized blood glucose and blood pressure monitoring were included in the nursing inter

| Blood glucose test indicators | No hypoglycemic risk drugs | Use of hypoglycemic risk drugs | ||||

| Good | Medium | Poor | Good | Medium | Poor | |

| HbA1c (mmol/L) | < 7.5 | < 8.0 | < 8.5 | 7.0–7.5 | 7.5–8.0 | 8.0–8.5 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.0–7.2 | 5.0–8.3 | 5.6–10.0 | 5.0–8.3 | 5.6–8.3 | 5.6–10.0 |

| 2hPBG (mmol/L) | 5.0–8.3 | 5.6–10.0 | 6.1–11.1 | 5.6–10.0 | 8.3–10.0 | 8.3–13.9 |

Regarding diet control, nutritionists developed individualized diets according to the patient’s condition and personal preferences. The rational distribution of the proportions of nutrition and salt intake was strictly limited (< 6 g/d), and smoking cessation and reduced alcohol consumption were ensured. In addition, the order of food consumption was adjusted to optimize the intake of protein, fat, and carbohydrates. Patients with a history of imbalanced dietary habits required additional vitamins and minerals.

Drug use guidance: Medication information was recorded in each patient’s file, and patients were instructed to strictly adhere to the prescribed timing and dosage instructions. Patients and their families received training in insulin injection techniques for cases requiring medication. Regular monitoring of vital signs was emphasized to ensure proper medi

Physical exercise: Before formulating a physical exercise program for patients, a risk assessment was performed based on the patient's medical history, family history, physical activity level, and relevant medical examination results. The primary forms of exercise included aerobic activities such as brisk walking, badminton, and Tai Chi. Patients exercised 5–7 d per week, with each session lasting 20–30 min, ideally scheduled 1 h after each meal.

Regarding psychological intervention, nursing staff assisted patients in regulating negative moods, promoting relaxation, and improving sleep quality by encouraging interpersonal communication. Patients' families were also informed to provide additional spiritual support and attend to their needs and desires. Furthermore, enhancing patients' understanding of their conditions through disease education helped foster a positive attitude toward treatment and care by dispelling misconceptions.

Evaluation of the intervention effects: The results were divided into three levels: A (met the standard), B (partially met the standard), and C (did not meet the standard). Re-evaluation could only be stopped and the study’s operational process could proceed after each nursing problem met the standard (Figure 2).

We compared fasting blood glucose (FBG), 2 h postprandial blood glucose (2hPBG), HbA1c, and blood pressure (DBP and SBP) before and after the intervention. Using the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36) for quality of life assessment, the patients' physical, emotional, mental, and overall health, as well as physiological function, were evaluated before and after the intervention. Furthermore, treatment compliance in the two groups was compared before and after the inter

Statistical software SPSS 21.0 (IBM, United States) was used for all analyses. Measurement data were expressed as the mean ± SD for the Student's t-test, while count data were expressed as percentages for the chi-squared test. P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

In the study group, there were 19 men and 21 women with an average age of 70.35 ± 4.26 years (62–78), an average diabetes duration of 9.13 ± 2.26 years (3–13), and an average hypertension duration of 5.30 ± 1.09 years (2–7). In the control group, there were 22 men and 18 women with an average age of 71.20 ± 4.18 years (60–81), an average diabetes duration of 8.80 ± 2.24 years (5–13), and an average hypertension duration of 5.28 ± 0.72 years (4–7). The differences in sex ratio, age, and disease duration between the two groups were not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

| Study group (n = 40) | Control group (n = 40) | t/χ2 value | P value | |

| Male/female | 19/21 | 22/18 | 0.450 | 0.502 |

| Age (yr) | 70.35 ± 4.26 | 71.20 ± 4.18 | 0.901 | 0.370 |

| Diabetes course (yr) | 9.13 ± 2.26 | 8.80 ± 2.24 | 0.646 | 0.520 |

| Hypertension course (yr) | 5.30 ± 1.09 | 5.28 ± 0.72 | 0.121 | 0.904 |

Before the intervention, there were no statistically significant differences in FBG, 2hPBG, or HbA1c levels between the two groups (P > 0.05). After the intervention, these indicators significantly decreased in both groups. However, compared with the control group, the improvements in these three indicators were more pronounced in the study group after the intervention, with the differences being statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

| FBG (mmol/L) | 2hPBG (mmol/L) | HbA1c (%) | ||||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Study group | 9.28 ± 0.82 | 5.79 ± 0.48a | 11.41 ± 1.20 | 6.75 ± 1.99a | 9.10 ± 1.96 | 6.45 ± 1.06a |

| Control group | 9.36 ± 0.75 | 7.54 ± 0.33a | 11.40 ± 1.34 | 8.79 ± 1.78a | 9.05 ± 1.04 | 7.44 ± 1.09a |

| t value | 0.404 | 19.060 | 0.076 | 4.815 | 0.128 | 4.303 |

| P value | 0.678 | < 0.001 | 0.940 | < 0.001 | 0.899 | < 0.001 |

In the context of blood pressure assessment before the intervention, there was no significant difference in DBP or SBP between the two groups (P > 0.05). After the intervention, a significant reduction in blood pressure metrics was observed in both groups (P < 0.05). The decrease in these indicators was more pronounced among patients in the study group compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

| DBP (mmHg) | SBP (mmHg) | |||

| Before | After | Before | After | |

| Study group | 100.23 ± 6.49 | 86.38 ± 4.75 | 162.60 ± 4.74 | 138.70 ± 7.34 |

| Control group | 98.35 ± 5.93 | 89.08 ± 4.21 | 163.45 ± 5.31 | 143.30 ± 6.65 |

| t value | 1.348 | 2.691 | 0.755 | 2.939 |

| P value | 0.181 | 0.009 | 0.453 | 0.004 |

The SF-36 questionnaire was used to assess multidimensional changes in patient's health status, including physical, emotional, social, and mental well-being, before and after nursing interventions. Initially, there were no significant differences in scores across various domains, such as physical, emotional, mental, and overall health, as well as physical function, between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, post-intervention, the study group demonstrated higher scores in these domains compared to the control group, with the most significant difference observed in the physical function domain (P < 0.05) (Table 6).

| Physical health | Emotion | Physiological function | Overall health | Mental health | |

| Before | |||||

| Study group | 63.45 ± 2.05 | 60.80 ± 2.40 | 65.60 ± 3.02 | 68.80 ± 1.16 | 60.48 ± 1.92 |

| Control group | 63.33 ± 2.12 | 61.18 ± 2.33 | 65.18 ± 3.20 | 68.48 ± 1.84 | 60.90 ± 2.24 |

| t value | 0.268 | 0.709 | 0.611 | 0.945 | 0.911 |

| P value | 0.789 | 0.480 | 0.543 | 0.347 | 0.365 |

| After | |||||

| Study group | 81.98 ± 2.74a | 78.90 ± 2.52a | 88.03 ± 2.26a | 89.43 ± 3.39a | 92.20 ± 2.09a |

| Control group | 75.05 ± 3.02a | 72.63 ± 2.87b | 76.73 ± 2.24a | 80.18 ± 2.32a | 88.90 ± 2.16a |

| t value | 10.737 | 10.390 | 22.458 | 14.248 | 6.947 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

After the intervention, the treatment compliance rate was 80.0% in the control group (32 cases of compliance and 8 of non-compliance) and 95.0% in the study group (38 cases of compliance and two cases of non-compliance). There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 4.114, P = 0.043).

The growing older population will exert substantial pressure on social security and pension service systems in the future. Nevertheless, we are committed to studying the healthcare needs of older adults, especially those with diabetes and hypertension. Building upon the outcomes of comprehensive assessments of older individuals, targeted intervention care should be implemented to address patients’ health needs, including physical health, psychological well-being, nutritional diet, safety, and health education. Targeted care provided by primary healthcare teams, based on a comprehensive assessment of older individuals’ health, can potentially improve their health and quality of life, especially those of advanced age[16].

Diabetes and hypertension are commonly encountered metabolic diseases among older adults, both of which can accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis, impair vascular function, and increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular events. These conditions are closely related to patients' dietary habits, level of physical activity, and psychological well-being[17]. Patients often require long-term medication to regulate their blood glucose and blood pressure levels. Factors such as misconceptions about their conditions, limited self-management skills, and poor treatment compliance can adversely affect the effectiveness of therapy[18]. Therefore, implementing comprehensive nursing interventions in hospitals is essential to enhance patient treatment outcomes.

CGA is widely used to diagnose and treat geriatric diseases. This model is patient-centered and comprehensively and systematically evaluates older patients from multidimensional levels of physical condition, cognitive ability, psychological state, and social support, which facilitates the development of individualized intervention programs[19]. In addition, CGA has demonstrated positive impacts in various areas, such as cancer treatment, where it aids in identifying patients at high risk of mortality and functional decline[20]. Regarding chronic kidney disease in the elderly, Chen et al[21] used CGA to comprehensively evaluate the levels of renal function, cognition, emotional state, nutritional status, and social support in different stages of the disease and guided patients’ health care. O'Shaughnessy et al[22] reported that CGA in the emergency department could lead to improved outcomes by reducing the negative impacts of potentially preventable hospital admissions.

The CGA aims to identify existing and potential clinical problems in patients, propose treatments to either maintain or improve functional status, and maximize or maintain the quality of life for older individuals. For example, Vu et al[23] developed a CGA questionnaire for diabetes management, including cognitive impairment, depression, urinary incontinence, dependence on daily living activities and instrumental activities, fall risk, hearing loss, visual acuity, polypharmacy, malnutrition, and the presence of multiple geriatric conditions. However, targeted nursing interventions were not provided. The CGA conducted in this study involves a multilevel assessment focusing mainly on the following aspects: medical assessment (MBI score), functional assessment (MNA score), psychological assessment (GDS score, HAMA score, PSQI score), and social assessment (MoCA score). Nursing interventions were carried out according to the assessment, including blood glucose and blood pressure monitoring, dietary control, medication guidance, physical exercise, and psychological intervention. Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in FBG, 2hPBG, and HbA1c levels between the two groups. However, after the intervention, these indicators were significantly decreased in both groups, especially in the study group. Concerning blood pressure indicators, there was no significant difference in DBP and SBP between the two groups before intervention. After the intervention, the blood pressure indexes of the two groups decreased significantly, with a more pronounced decrease observed in the study group. Using the SF-36 questionnaire, the researchers assessed changes in the health status of patients in multiple dimensions, such as physical, emotional, social, and mental well-being before and after receiving nursing interventions. At the beginning of the intervention, there was no significant difference in the scores of physical, emotional, mental, and overall health and physical function between the two groups but after the intervention, the scores of the study group in these fields were generally higher than those of the control group, especially in physical function. Furthermore, the treatment compliance rate of the control group after the intervention was 80.0%, while that of the study group reached 95.0%, which indicated that the study group performed better in treatment compliance. Overall, CGA-guided interventions help patients maintain normal blood glucose and blood pressure levels, improve their quality of life, and improve treatment compliance.

However, this study had limitations. First, this was a retrospective study which may have resulted in selection bias and incomplete record-keeping, limiting the generalizability of the results. Second, this study had a relatively small sample size, and the inclusion of patients from a single medical institution may have limited the broad applicability of the findings. Therefore, future research should consider adopting a prospective randomized controlled trial design conducted across multiple centers to enhance the external validity and robustness of the evidence.

The CGA nursing intervention significantly improved glycemic control, blood pressure management, and quality of life in hospitalized older patients with diabetes and hypertension, compared to routine care. The enhanced treatment adherence observed in the CGA group suggests that this model can potentially elevate the standard of care for geriatric patients. Therefore, CGA should be considered for broader implementation in similar patient populations to further optimize health outcomes.

| 1. | Liu Z, Agudamu, Bu T, Akpinar S, Jabucanin B. The Association Between the China's Economic Development and the Passing Rate of National Physical Fitness Standards for Elderly People Aged 60-69 From 2000 to 2020. Front Public Health. 2022;10:857691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3825] [Cited by in RCA: 4522] [Article Influence: 347.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang Y, Li R, Yuan L, Yang X, Lv J, Ye Z, Huang F, He T. Association between diabetes complicated with comorbidities and frailty in older adults: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32:894-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Meyer AM, Becker I, Siri G, Brinkkötter PT, Benzing T, Pilotto A, Polidori MC. The prognostic significance of geriatric syndromes and resources. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:115-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brigola AG, Luchesi BM, Alexandre TDS, Inouye K, Mioshi E, Pavarini SCI. High burden and frailty: association with poor cognitive performance in older caregivers living in rural areas. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2017;39:257-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1369] [Cited by in RCA: 1167] [Article Influence: 64.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ellis G, Whitehead MA, O'Neill D, Langhorne P, Robinson D. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD006211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kudelka J, Ollenschläger M, Dodel R, Eskofier BM, Hobert MA, Jahn K, Klucken J, Labeit B, Polidori MC, Prell T, Warnecke T, von Arnim CAF, Maetzler W, Jacobs AH; for the DGG working group Neurology. Which Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) instruments are currently used in Germany: a survey. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24:347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Duffy L, Gajree S, Langhorne P, Stott DJ, Quinn TJ. Reliability (inter-rater agreement) of the Barthel Index for assessment of stroke survivors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013;44:462-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van Exel NJ, Scholte op Reimer WJ, Koopmanschap MA. Assessment of post-stroke quality of life in cost-effectiveness studies: the usefulness of the Barthel Index and the EuroQoL-5D. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:427-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gana K, Bailly N, Broc G, Cazauvieilh C, Boudouda NE. The Geriatric Depression Scale: does it measure depressive mood, depressive affect, or both? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:1150-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5785] [Cited by in RCA: 5844] [Article Influence: 100.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, Soto ME, Rolland Y, Guigoz Y, Morley JE, Chumlea W, Salva A, Rubenstein LZ, Garry P. Overview of the MNA--Its history and challenges. J Nutr Health Aging. 2006;10:456-63; discussion 463. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11622] [Cited by in RCA: 15966] [Article Influence: 798.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pilz LK, Keller LK, Lenssen D, Roenneberg T. Time to rethink sleep quality: PSQI scores reflect sleep quality on workdays. Sleep. 2018;41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Choi JY, Lee JY, Shin J, Kim CO, Kim KJ, Hwang IG, Lee YG, Koh SJ, Hong S, Yoon SJ, Kang MG, Kim JW, Kim JH, Kim KI. COMPrehensive geriatric AsseSSment and multidisciplinary team intervention for hospitalised older adults (COMPASS): a protocol of pragmatic trials within a cohort. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tareen RS, Tareen K. Psychosocial aspects of diabetes management: dilemma of diabetes distress. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:383-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee CS, Tan JHM, Sankari U, Koh YLE, Tan NC. Assessing oral medication adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with polytherapy in a developed Asian community: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Carlson C, Merel SE, Yukawa M. Geriatric syndromes and geriatric assessment for the generalist. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:263-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hernandez Torres C, Hsu T. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in the Older Adult with Cancer: A Review. Eur Urol Focus. 2017;3:330-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chen X, Hu Y, Peng L, Wu H, Ren J, Liu G, Cao L, Yang M, Hao Q. Comprehensive geriatric assessment of older patients with renal disease: a cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep. 2024;14:8758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | O'Shaughnessy Í, Robinson K, Whiston A, Barry L, Corey G, Devlin C, Hartigan D, Synnott A, McCarthy A, Moriarty E, Jones B, Carroll I, Shchetkovsky D, O'Connor M, Steed F, Carey L, Conneely M, Leahy A, Quinn C, Shanahan E, Ryan D, Galvin R. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in the Emergency Department: A Prospective Cohort Study of Process, Clinical, and Patient-Reported Outcomes. Clin Interv Aging. 2024;19:189-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vu HTT, Nguyen TTH, Le TA, Nguyen TX, Nguyen HTT, Nguyen TN, Pham T, Nguyen AT. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients with Diabetes Mellitus in Hanoi, Vietnam. Gerontology. 2022;68:1132-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |