Published online Jun 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i17.3271

Revised: April 24, 2024

Accepted: May 6, 2024

Published online: June 16, 2024

Processing time: 86 Days and 3.9 Hours

Primary nasal tuberculosis (TB) is a rare form of extrapulmonary TB, particularly in patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) immunotherapy. As a result, its diagnosis remains challenging.

A 58-year-old male patient presented to the ear, nose, and throat department with right-sided nasal obstruction and bloody discharge for 1 month. He was diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis and received anti-TNF immunotherapy for 3 years prior to presentation. Biopsy findings revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation and a few acid-fast bacilli, suggestive of primary nasal TB. He was referred to our TB management department for treatment with oral anti-TB agents. After 9 months, the nasal lesions had disappeared. No recurrence was noted during follow-up.

The diagnosis of primary nasal TB should be considered in patients receiving TNF antagonists who exhibit thickening and crusting of the nasal septum mucosa or inferior turbinate, particularly when pathological findings suggest granulomatous inflammation.

Core Tip: Primary nasal tuberculosis is a rare form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (TB), particularly in patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor immunotherapy. The nasal cavity is most commonly involved; most infections involve the nasal septum and/or the inferior turbinate. We should remain vigilant for primary nasal TB in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists if the nasal mucosa of the nasal septum or the inferior turbinate demonstrates thickening or crusting, particularly when pathological findings suggest granulomatous inflammation. For suspected cases, repeated biopsies may enhance the identification of acid-fast bacilli.

- Citation: Liu YC, Zhou ML, Cheng KJ, Zhou SH, Wen X. Treatment of primary nasal tuberculosis with anti-tumor necrosis factor immunotherapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(17): 3271-3276

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i17/3271.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i17.3271

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) immunotherapy has revolutionized the treatment of inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and Crohn’s disease. However, this promotes reactivation, and possibly also acquisition, of intracellular pathogens including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, triggering potentially life-threatening infections. The frequency of tuberculosis (TB) associated with anti-TNF immunotherapy is much higher than that of any other opportunistic infection[1,2]. TB associated with anti-TNF immunotherapy is characterized by high rates of extrapulmonary and disseminated disease[3,4]. Primary nasal TB is a rare form of extrapulmonary TB, particularly in patients receiving anti-TNF treatment, with only few cases reported previously[5-10].

Primary nasal TB is associated with nonspecific manifestations, making its diagnosis challenging. We report a rare case of primary nasal TB in a patient receiving anti-TNF treatment who developed continuous nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and nasal crusting, aiming to raise awareness and recommend optimal treatment strategies for such patients.

A 58-year-old male patient presented to our ear, nose, and throat department with right-sided nasal obstruction and bloody discharge for 1 month in 2017.

Right-sided functional endoscopic sinus surgery had been performed 11 months prior. A histopathological examination performed at that time revealed nasal polyps. He underwent regular postoperative endoscopic follow-up; the nasal mucosa was normal for the first 9 months. However, during month 10, he developed right nasal stuffiness with a bloody discharge. There was no evidence of fever, cough, night sweats, headache, fatigue or weight loss.

He had been diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis in 2013 and was initially treated with methotrexate, glucosamine sulfate, and iguratimod; anti-TNF immunotherapy with adalimumab was started in 2014.

The patient denied any family history of positive TB.

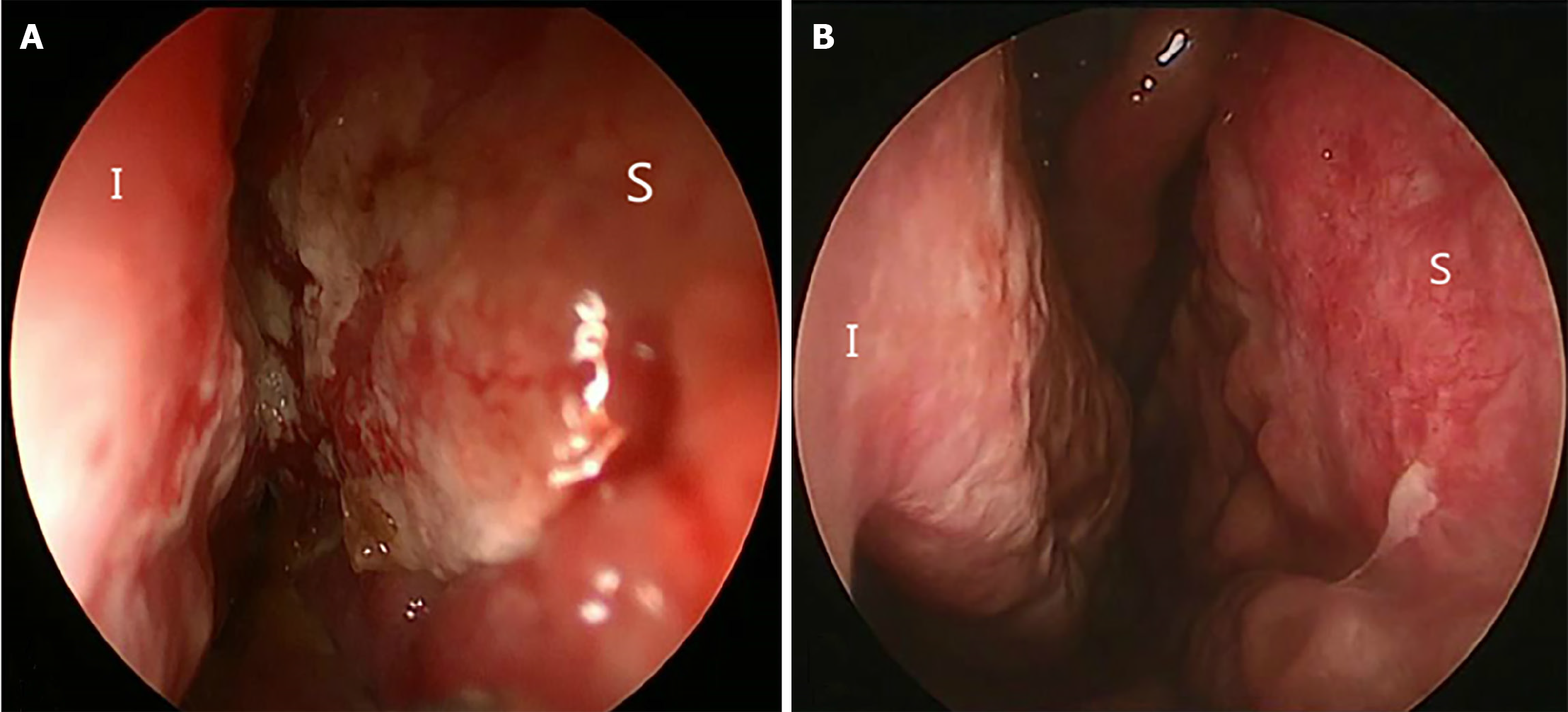

On examination, a nasal cavity obstruction was evident, as well as a severe crust. The mucosa over the septum and nasal cavity was grossly thickened and inflamed (Figure 1A). No abnormality was evident on external nasal and neck examination.

TSPOT TB tests performed in 2013–2016 were negative; the test performed in 2017 was positive. Human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis tests were negative.

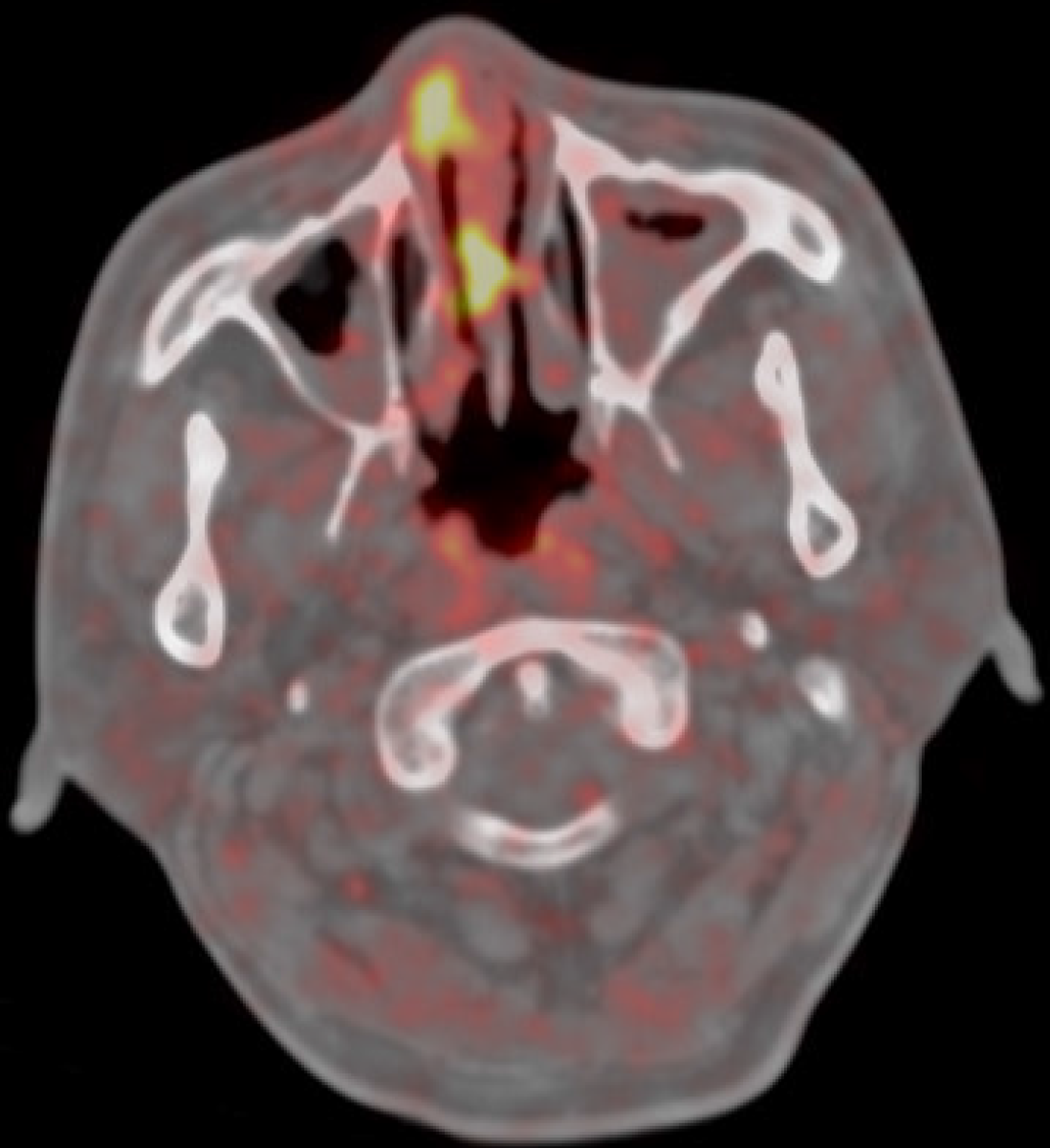

Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography revealed pathological hypercaptation of the right nasal cavity and septum (standardized uptake value: 10.9), raising a suspicion of malignancy (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the chest performed in 2014–2017 was normal.

The abnormal mucosa was endoscopically biopsied under local anesthesia; histology revealed obvious lymphoid tissue hyperplasia with extensive necrosis; we could not exclude a lymphoma. Repeat biopsy of the lesion revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation featuring T lymphocyte infiltration. A few acid-fast bacilli were noted on Ziehl–Neelsen staining (Figure 3). These findings suggested a diagnosis of primary nasal TB.

The patient was referred to our TB management department to receive oral anti-TB agents.

One month later, the symptoms improved and the nasal mucosa gradually became smooth (Figure 1B). After 9 months, the nasal lesions had disappeared. No recurrence was noted during follow-up.

Over the past 20 years, three TNF inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept) have emerged as effective therapies for patients with certain inflammatory diseases[11]. However, the increased clinical use of TNF antagonists has been accompanied by elevated levels of granulomatous infectious diseases, such as TB. TB associated with anti-TNF immunotherapy is characterized by high rates of extrapulmonary and disseminated disease.

Primary nasal TB associated with anti-TNFα therapy was first reported in 2013[10]. Here, we report another such case. Two previous patients had a long-term history of anti-TNF immunotherapy use for the treatment of psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis. Notably, both patients were TB-negative before commencement of TNF inhibitors, indicating that primary nasal TB should be considered in patients treated with TNF inhibitors who develop nasal crusting.

Primary nasal TB, a rare form of extrapulmonary TB, is challenging to differentiate from other diseases, given the lack of specific symptoms and signs. Most of us lack experience with this disease and some TB-related tests may not be performed in a timely manner, rendering diagnosis difficult. The symptoms of primary nasal TB are nonspecific, including nasal obstruction and discharge, crusting, epistaxis, and ulceroproliferative lesions of the external nose[5-9]. The nasal cavity is most commonly involved; most infections involve the nasal septum and/or the inferior turbinate. Septal lesions may manifest as bulges, masses, or perforations. The nasal mucosa may be thickened, inflamed, or fragile, and can exhibit granulomatous or ulcerative lesions, or crusting. The second most common site of involvement is the sinuses, mostly involving the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses, manifesting principally as a purulent discharge from the middle meatus, or facial swelling or an abscess. The lesions were in the external nose in a few cases, manifesting principally as lupus vulgaris, characterized by crusted ulceroproliferative lesions and later destruction of the carti

The typical pathological feature of primary nasal TB is granulomatous inflammation. However, granulomatous lesions within the nasal cavity may reflect a wide variety of diseases, including syphilis; mycobacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections; leprosy; systemic lupus erythematosus; and inflammatory diseases[7,12]. Definitive diagnosis is difficult when typical tubercular nodules or acid-fast bacilli are absent. In such cases, other tests need to be considered, and, sometimes, repeat biopsy may be required, as for our case. In our patient, the initial mucosal biopsy revealed lymphoid tissue hyperplasia with extensive necrosis, which could also be seen with lymphoma. However, subsequent repeat biopsy showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and a few acid-fast bacilli.

TB-PCR should be performed on routinely processed, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded histological specimens in patients with unclear diagnoses[13,14]. The recently developed interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) rapidly detects M. tuberculosis with high sensitivity and specificity, and is used both to diagnose infection and rule out active TB[15,16]. There is no strong evidence that the IGRA is superior to the TST in high- incidence low-resource countries. However, a growing number of guidelines and position papers now recommend use of the IGRA, primarily in low-incidence settings[17].

Although the diagnosis of primary nasal tuberculosis is challenging, its treatment is relatively simple. Timely treatment with anti-TB drugs can effectively control nasal tuberculosis[5-10]; surgery may not be required[7].

We should remain vigilant for primary nasal TB in patients treated with TNF antagonists if the nasal mucosa of the nasal septum or the inferior turbinate demonstrates thickening or crusting, particularly when pathological findings suggest granulomatous inflammation. For suspected cases, repeated biopsies may enhance the identification of acid-fast bacilli. Delayed diagnosis may lead to prolonged disease or spread of TB, with potentially life-threatening consequences.

| 1. | Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, Mirabile-Levens E, Kasznica J, Schwieterman WD, Siegel JN, Braun MM. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2608] [Cited by in RCA: 2491] [Article Influence: 103.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Miller EA, Ernst JD. Anti-TNF immunotherapy and tuberculosis reactivation: another mechanism revealed. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1079-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Theis VS, Rhodes JM. Review article: minimizing tuberculosis during anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:19-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hamdi H, Mariette X, Godot V, Weldingh K, Hamid AM, Prejean MV, Baron G, Lemann M, Puechal X, Breban M, Berenbaum F, Delchier JC, Flipo RM, Dautzenberg B, Salmon D, Humbert M, Emilie D; RATIO (Recherche sur Anti-TNF et Infections Opportunistes) Study Group. Inhibition of anti-tuberculosis T-lymphocyte function with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Butt AA. Nasal tuberculosis in the 20th century. Am J Med Sci. 1997;313:332-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Batra K, Chaudhary N, Motwani G, Rai AK. An unusual case of primary nasal tuberculosis with epistaxis and epilepsy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81:842-844. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kim YM, Kim AY, Park YH, Kim DH, Rha KS. Eight cases of nasal tuberculosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:500-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lai TY, Liu PJ, Chan LP. Primary nasal tuberculosis presenting with septal perforation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:953-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bhandary SK, Ranganna BU. Lupus vulgaris of external nose. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;60:373-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ribeiro S, Ferreira B, Duarte R, Almeida I, Vasconcelos C. Primary nasal tuberculosis during anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha treatment of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:957-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cantini F, Niccoli L, Goletti D. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and the risk of tuberculosis: data from clinical trials, national registries, and postmarketing surveillance. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2014;91:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chawla K, Gupta S, Mukhopadhyay C, Rao PS, Bhat SS. PCR for M. tuberculosis in tissue samples. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:83-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Park DY, Kim JY, Choi KU, Lee JS, Lee CH, Sol MY, Suh KS. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction with histopathologic features for diagnosis of tuberculosis in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded histologic specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:326-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li JY, Lo ST, Ng CS. Molecular detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tissues showing granulomatous inflammation without demonstrable acid-fast bacilli. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2000;9:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wen A, Qu XH, Zhang KN, Leng EL, Ren Y, Wu XM. Evaluation of interferon-gamma release assays in extrasanguinous body fluids for diagnosing tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Life Sci. 2018;197:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang L, Tian XD, Yu Y, Chen W. Evaluation of the performance of two tuberculosis interferon gamma release assays (IGRA-ELISA and T-SPOT.TB) for diagnosing Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;479:74-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Denkinger CM, Dheda K, Pai M. Guidelines on interferon-γ release assays for tuberculosis infection: concordance, discordance or confusion? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:806-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |