Published online Apr 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i11.1947

Peer-review started: November 4, 2023

First decision: January 9, 2024

Revised: January 27, 2024

Accepted: March 12, 2024

Article in press: March 12, 2024

Published online: April 16, 2024

Processing time: 158 Days and 15.6 Hours

Schwannomas are rare peripheral neural myelin sheath tumors that originate from Schwann cells. Of the different types of schwannomas, pelvic sciatic nerve schwannoma is extremely rare. Definite preoperative diagnosis of pelvic schwannomas is difficult, and surgical resection is the gold standard for its definite diagnosis and treatment.

We present a case of pelvic schwannoma arising from the sciatic nerve that was detected in a 40-year-old man who underwent computed tomography for intermittent right lower back pain caused exclusively by a right ureteral calculus. Subsequently, successful transperitoneal laparoscopic surgery was performed for the intact removal of the stone and en bloc resection of the schwannoma. The total operative time was 125 min, and the estimated blood loss was inconspicuous. The surgical procedure was uneventful. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 5 with the simultaneous removal of the urinary catheter. However, the patient presented with motor and sensory disorders of the right lower limb, caused by partial damage to the right sciatic nerve. No tumor recurrence was observed at the postoperative appointment.

Histopathological examination of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis of a schwannoma. Thus, laparoscopic surgery is safe and feasible for concomitant extirpation of pelvic schwannomas and other pelvic and abdominal diseases that require surgical treatment.

Core Tip: Schwannomas are rare peripheral neural myelin sheath tumors originating from Schwann cells. Pelvic sciatic nerve schwannoma is extremely rare. The clinical manifestations of pelvic schwannomas may be asymptomatic, viscerally oppressive, or neurological due to compression or invasion of the original nerves. Definite preoperative diagnosis of pelvic schwannomas is difficult, and surgical resection is the gold standard for definite diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of pelvic schwannoma arising from the sciatic nerve that was detected in a 40-year-old man who underwent computed tomography for intermittent right lower back pain caused exclusively by a right ureteral calculus. Subsequently, successful transperitoneal laparoscopic surgery was performed for the intact removal of the stone and en bloc resection of the schwannoma. Laparoscopic surgery is safe and feasible for concomitant extirpation of pelvic schwannomas and other pelvic and abdominal diseases that require surgical treatment.

- Citation: Xiong Y, Li J, Yang HJ. Concomitant treatment of ureteral calculi and ipsilateral pelvic sciatic nerve schwannoma with transperitoneal laparoscopic approach: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(11): 1947-1953

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i11/1947.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i11.1947

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a rare peripheral neural myelin sheath tumor originating from Schwann cells that provide proper nutrition and mechanical protection for axons and promote rapid saltatory excitation propagation[1]. Tumors may occur in any organ or nerve stem but are more common in the head, neck, and extremities[2]. Pelvic schwannomas arising mostly from the sacral nerve or hypogastric plexus is of rare occurrence[3]. Schwannoma of the sciatic nerve, which passes through the inferior piriformis foramen out of the pelvis and then generally divides into the tibial nerve and the common peroneal nerve at the top of the popliteal fossa, is a neurogenic tumor originating from the sacral plexus and can be grouped as a pelvic or extrapelvic schwannoma according to its location.

When pelvic schwannomas are small, they are usually asymptomatic, and most are found incidentally, such as when patients are examined for checkups or other unrelated diseases. Symptomatic pelvic schwannomas normally signify large volumes of tumors with compression of the surrounding vital tissues or apparatuses, such as the nerves, iliac vessels, urinary bladder, ureter, and intestines. Therefore, the clinical presentations of pelvic schwannomas are highly nonspecific and vary depending on tumor location and size[4]. The variability of symptoms leads to a clinically delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis of urological or gynecological diseases. Although it is difficult to completely remove a pelvic schwannoma because of its deep location and complex relationship with its surrounding tissues, the preferred first choice of treatment is complete surgical resection[5]. The preoperative diagnosis and surgical treatment of pelvic schwannomas remains a challenge for the urologists, gynecologists, and general surgeons.

A 40-year-old man presented with an intermittent dull right lower back pain over the past three months.

The patient had experienced intermittent dull right lower backache with frequent urination and urgency 3 months prior to presentation. Therefore, he sought medical attention at a local hospital. A urological computed tomography (CT) was performed, and the scan revealed a right upper ureteral stone and a low-density mass in the right pelvic space. Due to uncertainty about the right pelvic mass, local doctors referred the patient to our department for concomitant surgical resection of the right upper ureteral stone and ipsilateral pelvic mass.

The patient claimed that he was in good health, denied having any history of basic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease; infectious diseases such as hepatitis and tuberculosis; trauma and surgery; and drug and food allergy.

The patient was born and raised in the original place; had no history of contact with schistosomiasis water, infectious diseases, bad habits such as smoking and alcohol consumption, contact with toxic and radioactive substances, sexually transmitted diseases; and had no family history of hereditary diseases. His wife and children were healthy.

No tenderness or pain on percussion was observed in either of the renal region. The entire abdomen was soft with no palpable mass. No abnormalities were observed in the external genitalia. A digital rectal examination revealed no obvious findings.

Dry chemistry urinalysis revealed 108 leukocytes/μL and 173 red blood cells/μL. Repeat urine cultures were sterile. No significant abnormalities were observed in routine biochemical and hematological tests.

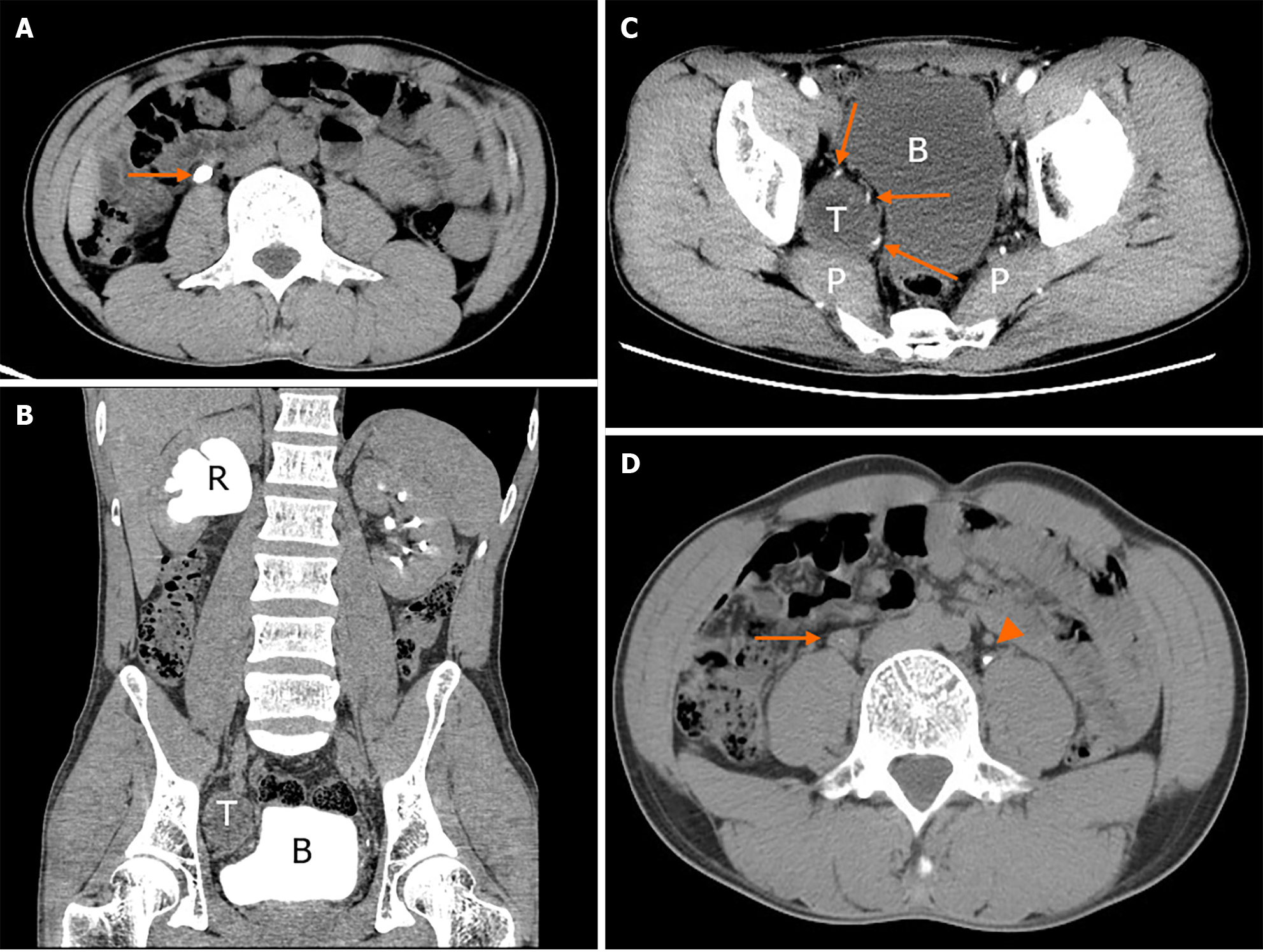

Chest radiography and electrocardiographic findings were normal. CT urography (CTU) showed a 2-cm right upper ureteral calculus with ipsilateral hydronephrosis, which was eventually found to be the main cause of the symptoms (Figure 1A and B). Simultaneously, a well-demarcated 5-cm homogeneous oval solid mass was observed in the right pelvic space without manifestations of any infiltration in the bladder, ureter, rectum, or other surrounding tissues (Figure 1B and C). In the arterial phase, branches of the internal iliac vessels were found in the anterior, medial, and posterior parts of the mass, and the boundary between the posterior part of the mass and the piriformis muscle was blurred (Figure 1C). In the excretion phase, the collection system above the stone was obviously dilated, and the ureter beneath the stone was still obviously dilated compared with the contralateral ureter; however, no obvious contrast agent was excreted (Figure 1D). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy were not performed.

The preoperative tentative diagnosis was pelvic schwannoma based on the CTU characteristics of the tumor.

The patient was counseled about all available treatment options, such as upper ureteral calculi, which could be removed through percutaneous nephrolithotomy, laparoscopic ureterolithotomy, or flexible ureteroscopic techniques, and the solid mass could be resected either laparoscopically or through robotic surgery. The patient eventually elected to undergo transperitoneal laparoscopic surgery for concomitant treatment of ureteral calculi and pelvic schwannoma. Following urethral catheterization and endotracheal intubation under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in a 45° left lateral decubitus position with a 15° Tredelenburg position, and a 4-trocar configuration was used. After the pneumoperitoneum was established using the Veress technique, a 10-mm trocar was placed through a 1.5-cm umbilical incision for a 30° endoscope (Karl Storz, Germany) and peritoneal insufflation with carbon dioxide. The pneumoperitoneum pressure was maintained at 12-14 mmHg. Another 10-mm trocar was inserted 3 cm from the right costal margin at the homolateral midclavicular line (MCL). A 10-mm trocar was inserted at the intersection of the right MCL and the horizontal line of the homolateral iliac crest, and a 5-mm trocar was inserted between the umbilicus and pubic symphysis. Following the mobilization of the right colon, a partial Kocher maneuver was performed to expose the upper segment of the right ureter and renal pelvis. The ureter was dissected until a stone was identified as a bulge. The ureter was incised longitudinally over the stone using a laparoscopic scalpel, and the stone was extracted using an endoscopic grasper. The ureter was implanted with a double-J stent (Cook Urological, United States) and successively sutured using interrupted 3-0 absorbable Vicryl sutures (Ethicon, United States). During exploration, the middle-upper ureter between the stone and mass was obviously dilated and hydrous, indicating compression of the pelvic mass on the surrounding ureter. The tumor was found beneath the right external iliac vessels and was dissected smoothly, except on the bottom side, which adhered firmly to the piriformis. In addition to the narrow space of the lateral pelvic wall, the tumor was difficult to dissect completely and was reluctantly incised. After removing the spilled myxoid material (Antoni B), which appeared as a hypodense shadow in the CT scan image, en bloc resection of the tumor was completed without visible injury to the surrounding tissues. Finally, a drain is placed in the Douglas pouch. The total operative time was 125 min, and the estimated blood loss was inconspicuous. The surgical procedure was uneventful.

The drain was withdrawn on postoperative day 2. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 5 with the simultaneous removal of the urinary catheter. The double-J stent was removed three weeks postoperatively. However, the patient presented with numbness in the anterior region of the right crus and dorsum of the right foot on the first postoperative day. Right foot drop, and thus difficulty in ambulation, was later observed. A subsequent neurophy

Schwannomas are generally well-circumscribed, slow-growing, solitary benign tumors, whereas multiple or malignant schwannomas are usually observed in patients with von Recklinghausen disease (neurofibromatosis) or schwannomatosis. The clinical manifestations of pelvic schwannomas may be asymptomatic, viscera-oppressive, or neurologic due to compression or invasion of the original nerves, often leading to a delayed diagnosis. Apart from clinical manifestations that lack preoperative diagnostic specificity, the radiological characteristics of schwannomas are insufficient to make a definite diagnosis because of their enormous variability. There are two main reasons for this significant radiological heterogeneity, the first is the different proportions of Antoni A and Antoni B components in schwannoma, and the second is usually because of the degenerative changes, such as tumor cystic transformation, calcification, hemorrhage, and hyalinization[6]. Alterations in these elements lead to changes in schwannomas on CT and MRI scans. However, radiological modalities are not all helpful and contribute to displaying tumor size, location, and relationships with the surrounding structures[7]. In the present case, abdominal CT revealed a low-density mass in the right lateral pelvic wall. Delayed marginal enhancement did not occur until the CTU excretion phase was achieved. One of the most important radiological findings is the abundance of blood supply to the mass, which is a critical indicator of strict bleeding control and a clear surgical field.

Radiological modalities guided by FNA were not performed in our case to avoid biopsy-related bleeding and intestinal injuries resulting from the intractable anatomical characteristics of the tumor. Although previous and recent studies have recommended FNA biopsy for a definite preoperative diagnosis[8,9], most studies have concluded that FNA is of limited value[3,6,10]. They do not recommend routine preoperative FNA biopsy for the following reasons: (1) Cellular pleomorphism may mislead the interpretation of microscopic results; (2) The manipulation may complicate bleeding, infection and tumor seeding; and (3) FNA specimens cannot be embedded in paraffin or immunohistochemically stained. Therefore, en bloc resection is the gold standard for definite diagnosis and treatment of schwannomas.

En bloc resection of pelvic schwannomas can be performed using open, laparoscopic, or robot-assisted approaches. The goal of schwannoma resection using any approach is to eradicate the tumor while preserving pelvic organ function whenever possible. With the rapidly increasing application of endoscopic techniques in surgery, the acceptance of (robot-assisted) laparoscopic resection as an alternative to open resection for pelvic schwannomas is increasing. Konstantinidis et al[11] reported that laparoscopy is a safe and efficient option for treating pelvic schwannomas and may offer the advantage of better exposure owing to the magnification of the laparoscopic view, especially in narrow anatomic pelvic spaces. Ningshu et al[12] also commented that laparoscopic extirpation of pelvic schwannomas is superior to open surgery in terms of postoperative rehabilitation, pain, hospital stay, and oncological results. However, four of the six enrolled patients in their study developed different degrees of neurological deficits. Robotic surgical systems have been gradually developed to reduce the incidence of neurological complications because of their hand-eye coordination, high-definition 3D view of the surgical field, and seven degrees of freedom[13]. These advantages are particularly important for robotic surgical systems for separating delicate and vulnerable anatomical structures in a narrow operating space. In our case, the patient finally underwent laparoscopic surgery because of subjective aspiration for concomitant removal of the ureteral calculi and ipsilateral pelvic tumor. Our laparoscopic resection of the schwannoma was uneventful, with excellent one-year postoperative oncological results. However, the patient presented with motor and sensory disorders of the right lower limb, and subsequent electrophysiological analysis suggested that it was caused by partial damage to the right sciatic nerve. According to the postoperative condition analysis conducted by our surgical team, the dissection of the tumor root was probably too difficult to protect the sciatic nerve branches because of the narrow lateral pelvic spaces, abundant blood supply to the tumor root, and tight adhesion with the sciatic nerve. Wang et al[14] also reported a similar successful resection of intrapelvic sciatic schwannoma through laparoscopic surgery, in which the patient experienced a transient numbness in the right heel after surgery. They concluded that the laparoscopic approach used for treating intrapelvic schwannomas of the sciatic nerve was safe and feasible under the guarantee of comprehensive preoperative preparation because of the patient’s condition and sufficient experience from the surgeon with regard to laparoscopic surgery on pelvic tumors. In the past, our center has carried out approximately 40 laparoscopic radical prostatectomies and 25 laparoscopic radical cystectomies annually. Since the introduction of the Da Vinci robotic system, approximately 35 robotic radical prostatectomies and 20 robotic radical cystectomies have been performed annually. Based on these findings, laparoscopic or robotic surgery is feasible for patients for the simultaneous treatment of ureteral stones and ipsilateral intrapelvic sciatic nerve schwannomas. Woo et al[15] published an interesting case of sciatica, and subsequent surgical results confirmed that sciatica was caused by an intrapelvic sciatic notch schwannoma. Successful excision was achieved via a transgluteal subpiriformis approach. This approach was not adopted in our patient, mainly due to concerns about the need for a large skin incision and unfamiliarity of anatomical pathways.

In our case, combined with literature reviews, we firstly proposed an analysis method to achieve ideal schwannoma resections, called the “trifecta”, which were free of radiological recurrence, early complications and neurological damages. To achieve this goal, our suggestions for pelvic schwannoma resection are as follows: (1) Adjuvant use of intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring may decrease the incidence of neurological damage; (2) Preoperative multidisciplinary treatment (MDT) involving urology, obstetrics and gynecology, neurosurgery, and general surgery is strongly recommended to achieve the trifecta goal; and (3) Strict hemostatic techniques may avoid unnecessary side injuries.

The preoperative diagnosis of schwannoma is difficult; most are suspected diagnoses, and the final definite diagnosis still requires surgical removal of the gross specimens. The trifecta goal can be achieved using laparoscopic surgery for pelvic schwannoma resection, especially when patients have other urological, general, or gynecological diseases that require surgical removal. MDT cooperation, intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring, and strict hemostatic techniques will further compensate for the limitations of laparoscopic surgery. To conclude, laparoscopic surgery is safe and feasible for concomitant extirpation of pelvic schwannomas and other pelvic and abdominal diseases that require surgical treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nayak S, India S-Editor: Zheng XM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Niepel AL, Steinkellner L, Sokullu F, Hellekes D, Kömürcü F. Long-term Follow-up of Intracapsular Schwannoma Excision. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82:296-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Nishitani H, Uehara H. Ancient schwannoma of the female pelvis. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:247-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Deboudt C, Labat JJ, Riant T, Bouchot O, Robert R, Rigaud J. Pelvic schwannoma: robotic laparoscopic resection. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:2-5; discussion 5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Freitas B, Figueiredo R, Carrerette F, Acioly MA. Retroperitoneoscopic Resection of a Lumbosacral Plexus Schwannoma: Case Report and Literature Review. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2018;79:262-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang CC, Chen HC, Chen CM. Endoscopic resection of a presacral schwannoma. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:86-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Daneshmand S, Youssefzadeh D, Chamie K, Boswell W, Wu N, Stein JP, Boyd S, Skinner DG. Benign retroperitoneal schwannoma: a case series and review of the literature. Urology. 2003;62:993-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoshino T, Yoneda K. Laparoscopic resection of a retroperitoneal ancient schwannoma: a case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2889-2891. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ferretti M, Gusella PM, Mancini AM, Mancini L, Vecchi A. Progressive approach to the cytologic diagnosis of retroperitoneal spindle cell tumors. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:450-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Strauss DC, Qureshi YA, Hayes AJ, Thomas JM. Management of benign retroperitoneal schwannomas: a single-center experience. Am J Surg. 2011;202:194-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Petrucciani N, Sirimarco D, Magistri P, Antolino L, Gasparrini M, Ramacciato G. Retroperitoneal schwannomas: advantages of laparoscopic resection. Review of the literature and case presentation of a large paracaval benign schwannoma (with video). Asian J Endosc Surg. 2015;8:78-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Konstantinidis K, Theodoropoulos GE, Sambalis G, Georgiou M, Vorias M, Anastassakou K, Mpontozoglou N. Laparoscopic resection of presacral schwannomas. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15:302-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ningshu L, Min Y, Xieqiao Y, Yuanqing Y, Xiaoqiang M, Rubing L. Laparoscopic management of obturator nerve schwannomas: experiences with 6 cases and review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:143-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Konstantinidis KM, Hiridis S, Karakitsos D. Robotic-assisted surgical removal of pelvic schwannoma: a novel approach to a rare variant. Int J Med Robot. 2011;7:55-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang R, Li S, Liu C, Gao F, Xu X, Niu B, Wu B. Laparoscopic excision for intrapelvic schwannoma of the sciatic nerve: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 2023;25:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Woo PYM, Ho JMK, Ho JWK, Mak CHK, Wong AKS, Wong HT, Chan KY. A rare cause of sciatica discovered during digital rectal examination: case report of an intrapelvic sciatic notch schwannoma. Br J Neurosurg. 2019;33:562-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |