Published online Mar 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i9.2021

Peer-review started: November 14, 2022

First decision: January 12, 2023

Revised: January 25, 2023

Accepted: March 3, 2023

Article in press: March 3, 2023

Published online: March 26, 2023

Processing time: 123 Days and 4.9 Hours

Small bowel adenocarcinomas (SBA) are rare malignancies with exceedingly low survival rates, with different presentation in Crohn’s disease (CD). CD-induced SBA poses diagnostic challenges given overlapping presentation with stricturing CD and lack of diagnostics for early detection. Moreover, guidance is lacking on the impact of recently approved therapeutics in CD on SBA management. Here, we aim to highlight the future of CD-induced SBA management and discuss the potential merit of balloon enteroscopy and genetic testing for earlier detection.

We report the case of a 60-year-old female with longstanding Crohn’s ileitis, presenting with acute obstructive symptoms attributed to stricturing phenotype. Her obstructive symptoms were refractory to intravenous (IV) steroids, with further investigation via computed tomography enterography not providing additional diagnostic yield. Ultimately, surgical resection revealed SBA in the neoterminal ileum, with oncologic therapy plan created. However, this therapy plan could not be initiated due to continued obstructive symptoms attributed to active CD. Ultimately, infused biologic therapy was initiated, but her obstructive symptoms continued to remain dependent on IV corticosteroids. Review of diagnostics by a multidisciplinary care team suggested metastatic disease in the peritoneum, lending to a shift in the goals of care to comfort.

With the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of concurrent SBA and CD, multidisciplinary care and algorithmic management can optimize outcomes.

Core Tip: The prognosis of Crohn’s disease-induced small bowel adenocarcinomas (SBA) depends largely on staging at diagnosis, with early detection resulting in potentially improved outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach with gastroenterology, colorectal surgery, and radiology is key to this early diagnosis. Initially, a thorough family history can aid in decision-making with earlier intervention in those with stricturing phenotype and suggestion of higher colorectal cancer risk or syndrome. If imaging shows atypical features such as a mass, retrograde balloon enteroscopy should not be delayed. Finally, when surgical resection is considered in strictures refractory to medical therapy, lymph node sampling can aid in surgical staging of the SBA.

- Citation: Karthikeyan S, Shen J, Keyashian K, Gubatan J. Small bowel adenocarcinoma in neoterminal ileum in setting of stricturing Crohn’s disease: A case report and review of literature . World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(9): 2021-2028

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i9/2021.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i9.2021

Small bowel adenocarcinomas (SBA) are rare malignancy that originate from the epithelial lining of the small intestine and progressively invade deeper layers of tissue. A systematic review and meta-analysis[1] of eight studies comprising 7344 patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) estimated the standardized incidence ratio of small bowel cancer to be 22.01. Risk factors for SBA include hereditary mutations, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[1-3]. More recent work suggests CD-induced SBA may be a separate entity than de novo SBA, driven by mutations of different genes and presenting in younger populations.

Patients with CD-induced SBA typically present with intermittent abdominal pain, weight loss, and nausea, but delays in diagnosis result in 33% of patients presenting with an intestinal obstruction[4]. Diagnostic challenges arise given the similar presentation to fibrostenotic CD. Highly specific and sensitive radiological methods can detect SBA but typically once it has caused an obstruction late in the disease course, greatly diminishing prognosis[5]. The current mainstay approach for both SBA and fibrostenotic CD remains surgical resection with histopathology.

CD-induced SBA is a rare phenomenon, and as the therapeutic landscape for CD expands, there presents more opportunity for variation in phenotype, progression, and therapy. Here we present a case of CD-induced SBA in a 60-year-old female with a history of Crohn’s ileitis refractory to intravenous (IV) steroids and biologic therapy, presenting with neoterminal ileal obstructions and hepatic consolidation. Through a literature review of previous cases we investigate clinical features and prognostic factors and subsequently propose the use of novel diagnostic techniques for early detection of malignancy.

A 60-year-old female with a 30-year history of poorly controlled stricturing small bowel CD (Montreal L1B2) presented with abdominal pain and nausea.

She was admitted with several weeks of increasing nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, inability to pass gas or stool. She denies fevers, chills, change in bowel movements, or hematochezia.

The patient was diagnosed with CD 30 years ago, managed largely with mesalamine and courses of corticosteroids. About 15 years after her initial diagnosis, she presented with small bowel obstruction and underwent an exploratory surgery with small bowel resection. She was subsequently treated with corticosteroids with plans for biologic-based treatment which was cost-prohibitive. She was lost to follow-up until she presented more recently with recurrent obstructive symptoms.

She denied family history of malignant tumors, including small and large bowel malignancy.

On physical exam, she was afebrile and well-developed, well-nourished. She was clearly uncomfortable with distension. She had diffused abdominal tenderness without rebound or guarding. Her exam was otherwise unremarkable.

Initial labs most notable for an elevated fecal calprotectin 448 (normal < 50 mcg/mg) and normal C-reactive protein. Stool tests (Clostridium difficile and gastrointestinal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were negative for infection.

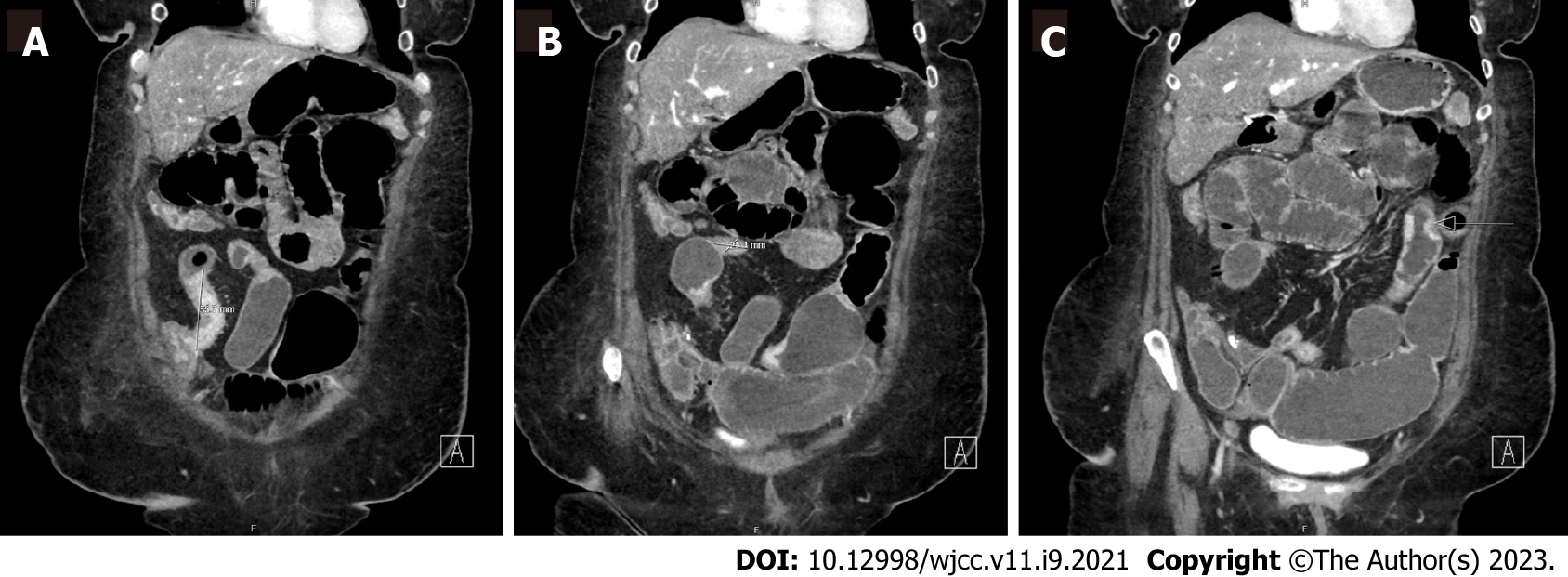

The patient underwent a computed tomography (CT) enterography which demonstrated multifocal stricturing, predominantly of the ileum, with progressive partial small bowel obstruction. There was no clear intra-luminal or submucosal mass visualized in the small bowel (Figure 1). Given longstanding untreated small bowel CD and elevated calprotectin, the presentation was concerning for small bowel obstruction in the setting of mixed inflammatory and fibrostenotic strictures.

The final diagnosis was metastatic CD-SBA.

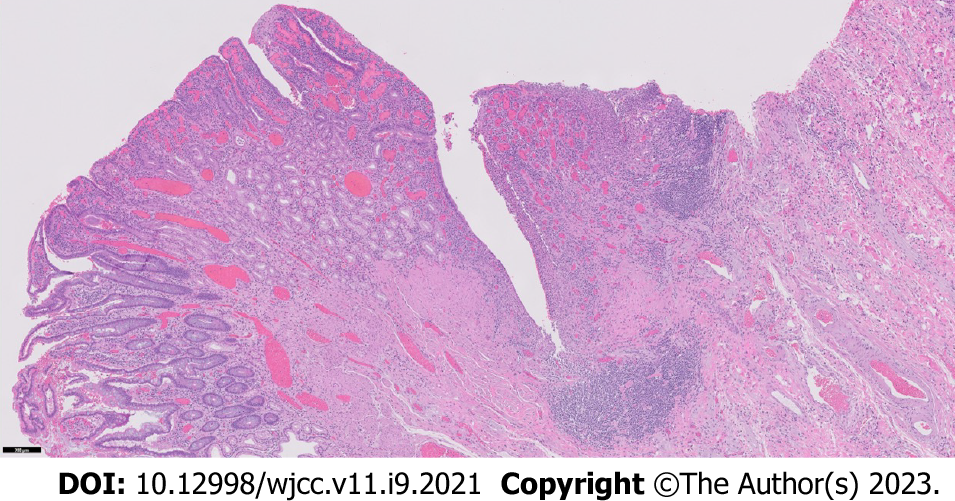

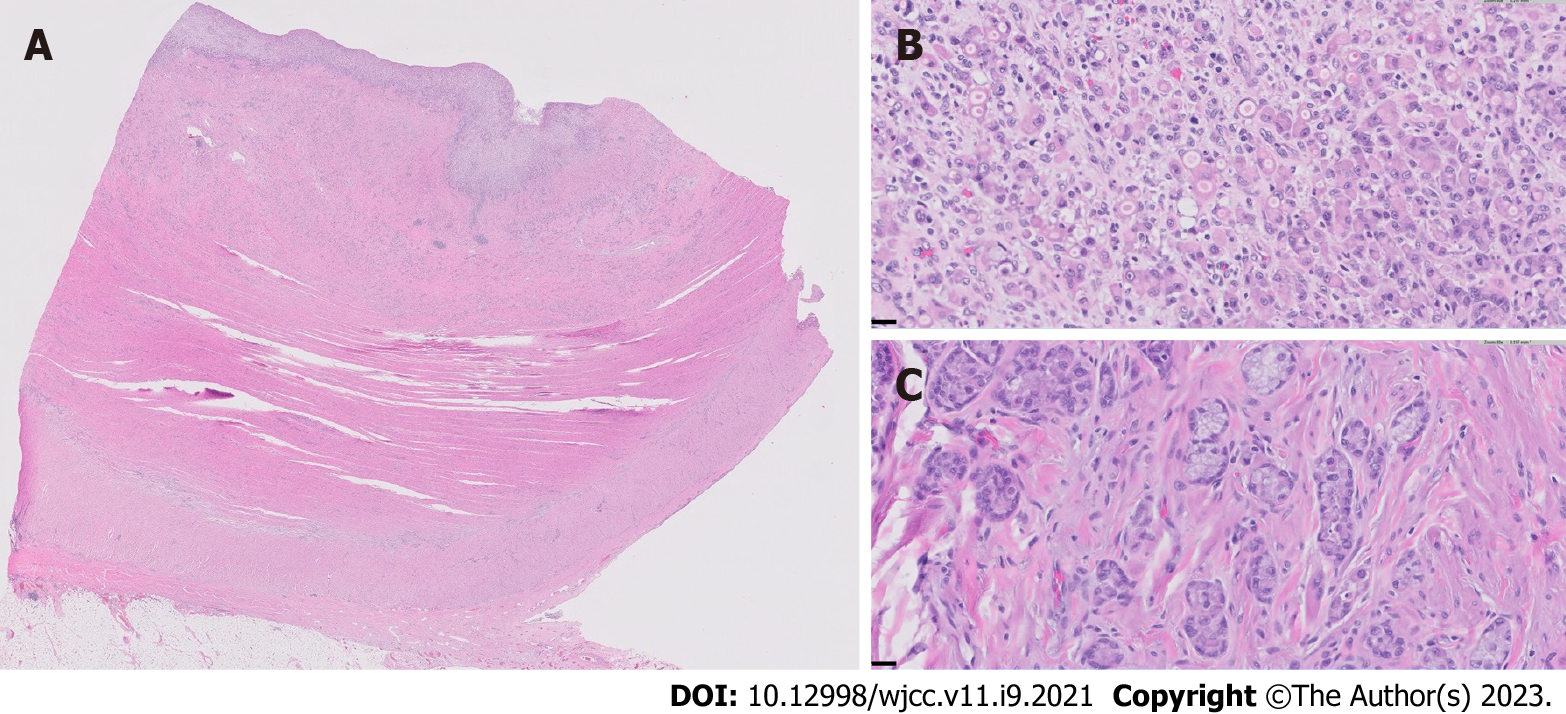

Her case was managed in a multidisciplinary fashion, with input from gastroenterology, colorectal surgery, and radiology. Despite IV corticosteroids, she continued to have obstructive symptoms and, ten days later, the decision was made for a repeat ileocecectomy with end ileostomy. Histopathologic examination of the background ileum showed severe chronic active ileitis with cryptitis (Figure 2) consistent with active Crohn’s disease. Histopathologic examination of the resected ileocolic anastomosis revealed a poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma comprised of sheets of single malignant cells with signet-ring morphology. Well-differentiated areas (tubules with small rigid lumina and polarized tumor cell clusters without a distinct lumina) were also identified (Figure 3). The ileum proximal to the tumor displayed a background of chronic active ileitis. Metastatic carcinoma was also found in 6/235 lymph nodes. She was subsequently discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

The patient was readmitted with recurrent obstructive symptoms with CT imaging showing a partial small bowel obstruction with a transition point in the proximal jejunum. The patient had a response to IV methylprednisolone but had recurrence of symptoms after transitioning to oral prednisone. Her case was discussed at a multidisciplinary conference, with a focus on risks and benefits of escalation to biologic therapy. After shared decision-making, infliximab was initiated, and the patient obtained two doses taken alongside IV solumedrol. She continues to remain dependent on IV corticosteroids.

Subsequent CT and positron emission tomography scan demonstrated metastatic hepatic involvement, loculated ascites, and omental nodularity concerning for peritoneal carcinomatosis, and the focus of care was transitioned to comfort measures only. Patient’s perspective was not available.

Neoplasms of the small bowel comprise 2.4%[6] of all gastrointestinal cancers and the rarity in comparison to CRC is thought to be due to the fluid, alkaline and immunoglobulin A rich nature of the small intestine[7]. SBA describes the malignant transformation of glandular epithelia and is the most prevalent malignancy of the types of small intestine cancers[8]. The incidence of small bowel cancers in the United States have risen from 1.18/100000 in 1973[3] to 2.5/100000 in 2021[9], and are 1.5 to 2 times more common in males than females[9]. Known risk factors include consumption of alcohol, smoked foods and refined carbohydrates, a background of hereditary cancer syndromes including familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary nonpolyposis CRC or IBD[10]. SBA tends to localize to the duodenum and jejunum, while a small percentage localize to the ileum[11]. This is in contrast to CD-induced SBA, where the ileum is most commonly involved.

The prevalence of SBA is markedly higher in CD patients, at 1.15 per 1000 CD patients[12], A study done by Yu et al[13] determined the standardized infection ratio (SIR) of SBA in CD to be 8.3, with the SIR for stricturing CD being 14.7 per 100000 person years. The eight-fold increase in risk for SBA in a background of CD warrants active surveillance methods and development of an effective algorithm for the detection and diagnosis of SBA.

Recent work suggests major differences in the pathogenesis of de novo SBA and CD-induced SBA[8]. CD-induced SBA thought to be caused by a predisposed gastrointestinal environment of chronic inflammation[14,15]. The environment increases permeability of carcinogens and promotes malabsorption of anti-carcinogenic compounds[16]. Longstanding CD results in cycles of inflammation and scar tissue formation, resulting in mutagenesis of genes implicated in tumor suppression and chromatin remodeling leading to an increased risk of carcinogenesis. Molecular differences between de novo SBA and CD-induced SBA indicate the implication of different carcinogenic pathways[15]. A prospective analysis reveals CD-induced SBA is predominantly driven by mutations of CDKN2A/B, CASP8 and ATRX[9].

There is little information directing management of the disease, resulting in many cases being treated as an extrapolation from CRC due to overlap in the drivers of molecular pathogenesis and lack of knowledge surrounding the progression of SBA[17]. The presentation is nonspecific lending to an average delay in diagnosis of 6 to 12 mo. In light of this delay in diagnosis, SBA has a markedly decreased 5-year survival rate at 34.9% and increase in prevalence, as opposed to the 51.5% 5 year survival rate in CRC and decline in prevalence[18].

A prior study using the National Cancer Database[19] involving 493 patients with CD-associated SBA and 2175 with sporadic SBA demonstrated that CD-associated SBA were more likely to present at a younger age, have tumors located in the ileum, and have poorly differentiated tumors compared to sporadic SBA. The typical age of diagnosis of de novo SBA is 60-69 years, whereas CD-induced SBA is 45-55 years, with diagnosis of CD usually predating diagnosis of SBA by 20 years[20]. SBA is also more likely to affect males (62.5%-80%)[21]. Family history of colorectal cancer (CRC) and potential cancer syndromes are also important risk factors, highlighting the need for a thorough family history. In addition, a prior multi-center case-control study[22] suggested that a prior small bowel resection and prolonged salicylate treatment (> 2 years) were associated with decreased risk of SBA in CD.

In contrast to these known risk factors, our patient’s gender and age did not fit typical demographics of CD-induced SBA and her symptoms were readily attributable to stricturing CD, signifying the need to broaden conceptualizations regarding demographic trends. In addition she developed SBA despite having a prior small bowel resection and being on long-term mesalamine therapy.

The pathogenesis of CD-induced SBA suggests the prospect of genetic testing in refractory CD to investigate potential risk factors for malignancy development. Advances in liquid biopsy allow for the detection of tumor related markers through analysis of ctDNA, cfDNA and circulating tumor derived endothelial cells in samples of biological fluids[23]. Recent work describes the merits of this method in the detection and real time monitoring of CRC, allowing repeated temporal sampling for detection at curable stages[24-26]. A study done by Zhong et al[27] found that mesenchymal cell marker vimentin (M-CTC) in liquid biopsy directly correlated with tumor size, tumor, node and metastasis stage and vascular invasion. Unfortunately, the cost of liquid biopsy[26] outweighs its feasibility as a screening method, warranting discovery of affordable techniques that serve the same purpose for SBA. Nevertheless, these techniques could be applied to high-risk phenotypes, such as stricturing CD.

Resection is an invasive process with several associated risks, posing the need to explore novel less invasive diagnostic techniques. Currently CT and magnetic resonance enterography provide high specificity and sensitivity in the detection of stricturing malignant lesions at lesions at 98% and 95%[28] respectively. If a mass is seen on these imaging modalities, further diagnostics could be pursued. However, the shortcomings of cross-sectional imaging include lack of ability to distinguish CD-related stricturing from malignancy; neither of these methods can allow for examination of cellular morphology like histopathology, which is why both methods must be combined for definitive diagnosis of malignancy.

Independent of imaging finding of a mass, a method that is able to evaluate the investigate a significant length of the gastrointestinal tract and the strictured area whilst allowing for biopsy, delivery of therapy and tattooing the lesion as a marking for subsequent surgery double balloon enteroscopy (DBE)[29]. DBE has a 85.9% positive rate of diagnosis opposed to the 72.9% of CT[30]. A case in 2021 was able to harness DBE to diagnose SBA presence and progression prior to surgery[31], allowing for early confirmation of peritoneal dissemination via laparoscopy prior to resection.

The mainstay treatment for SBA remains to be surgical resection of the primary tumor and loco-regional lymph node resection. This may be accompanied with chemotherapy in between surgeries if multiple surgeries are required to resect the mass. In the case that the final ileal loop is affected, an ileocecal or right hemicolectomy with ligation of the ileocolic artery is recommended[14].

Patients with lymph node involvement have a 32% 5-year overall survival (OS) compared to the 52% of patients without lymph node involvement[14]. Moreover, patients with over 75% lymph node involvements had a 12% 5-year OS as opposed to 51% in patients with less than 75% lymph node involvement[14]. 5-year OS for resected vs non resected tumors are 40-60% and 15-30% respectively[14]. Recent work has shown very minimal improvement in prognosis when adjuvant chemotherapy such as fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin are used in conjunction with surgery for stage 3 disease[14]. However, retrospective studies do indicate the efficacy of chemotherapy in non-surgically treated patients, showing an OS of 12 mo vs 2 mo for chemotherapy treated and non-treated respectively[12]. Generally, when chemotherapy is pursued, patients with concomitant IBD stop biologic treatments until the course of chemotherapy is complete due to increased risk of carcinogenesis with immunosuppression[13].

Our patient was started on infliximab alongside IV steroids, prior to development of ascites and metastatic hepatic involvement representative of peritoneal carcinomatosis. While there have been some small studies that have correlated infliximab therapy to either development or rapid progression of colorectal adenocarcinoma, larger studies show similar progression as a basline population[32-34]. Further larger studies can clarify the association between the usage of anti-TNF therapy and incidence of malignancy to justify the merit of anti-TNF biologics to treat CD in patients with risk factors for small bowel cancer progression or recurrence.

This case is unique regarding the patient’s demographics which challenge what is currently expected in patients with CD induced SBA, making diagnosis difficult, especially when paired with insignificant imaging. Our case highlights the need for multidisciplinary care for management of CD-induced SBA. Medical gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons, radiologist, specialized pathologists, and medical oncologists are key elements of the team to expedite diagnosis and delineate treatment.

Through this case, we propose an approach for earlier detection of SBA in CD patients. First, identification of a CRC risk or syndrome in the setting of stricturing ileal CD warrants evaluation of the stricture DBE. Furthermore, symptomatic strictures unresponsive to therapy should head to surgery early in the course of hospitalization. Finally, during the surgical approach, sampling of the lymph nodes to understand the staging of SBA. These different stages should be approached in a multidisciplinary fashion.

Although this study provides insight into a novel presentation of CD induced SBA, this case report is limited primarily by clinical follow up and sample size. While we provide one algorithm to treatment, a prospective multicenter trial would be needed to validate the recommendations and conclusions made in this study. Moreover, the limited clinical follow up may have skewed results.

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing SBA in longstanding CD. It emphasizes that the absence of an apparent mass on cross-sectional imaging in a patient with CD and bowel obstruction does not rule out malignancy, underlining the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis in patients with nonrefractory, obstructive CD. SBA is a recognized complication of CD. Studies identifying clinical factors to risk stratify patients who will develop small bowel malignancy in CD are lacking. Future studies are needed to explore strategies for early detection and prevention of SBA among patients with CD.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Knudsen T, Denmark; Tajra JBM, Brazil S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Annese V. Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma in Crohn's Disease: An Underestimated Risk? J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:285-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Occhipinti M, Botticell A, Onesti CE, Ghidini M, Righini R, Pizzo C, Milano A, Tomasello G, Di Pietro FR, Toppo L. Treatment and outcome for small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA): a real life experience of two Italian centres. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:vi50. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Palascak-Juif V, Bouvier AM, Cosnes J, Flourié B, Bouché O, Cadiot G, Lémann M, Bonaz B, Denet C, Marteau P, Gambiez L, Beaugerie L, Faivre J, Carbonnel F. Small bowel adenocarcinoma in patients with Crohn's disease compared with small bowel adenocarcinoma de novo. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:828-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dasari BV, Gardiner KR. Management of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2009;3:121-122. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Li J, Wang Z, Liu N, Hao J, Xu X. Small bowel adenocarcinoma of the jejunum: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Paski SC, Semrad CE. Small bowel tumors. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:461-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calman KC. Why are small bowel tumours rare? Gut. 1974;15:552-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cancer.Net. Small Bowel Cancer. Introduction. [cited 9 November 2022]. Available from: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/small-bowel-cancer/introduction. |

| 9. | SEER Cancer. Cancer Stat Facts: Small Intestine Cancer. [cited 28 June 2022]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/smint.html. |

| 10. | Quinones GAO, Suheb MZK, Woolf A. Small Bowel Cancer. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2022. |

| 11. | Halfdanarson TR, McWilliams RR, Donohue JH, Quevedo JF. A single-institution experience with 491 cases of small bowel adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2010;199:797-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chin YH, Jain SR, Lee MH, Ng CH, Lin SY, Mai AS, Muthiah MD, Foo FJ, Sundar R, Ong DEH, Leow WQ, Leong R, Chan WPW. Small bowel adenocarcinoma in Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence, manifestation, histopathology, and outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37:239-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yu J, Refsum E, Perrin V, Helsingen LM, Wieszczy P, Løberg M, Bretthauer M, Adami HO, Ye W, Blom J, Kalager M. Inflammatory bowel disease and risk of adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors in the small bowel. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:649-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aparicio T, Zaanan A, Svrcek M, Laurent-Puig P, Carrere N, Manfredi S, Locher C, Afchain P. Small bowel adenocarcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:97-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pandya K, Overman MJ, Gulhati P. Molecular Landscape of Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Caio G, Volta U, Ursini F, Manfredini R, De Giorgio R. Small bowel adenocarcinoma as a complication of celiac disease: clinical and diagnostic features. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pedersen KS, Raghav K, Overman MJ. Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma: Etiology, Presentation, and Molecular Alterations. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1135-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Young JI, Mongoue-Tchokote S, Wieghard N, Mori M, Vaccaro GM, Sheppard BC, Tsikitis VL. Treatment and Survival of Small-bowel Adenocarcinoma in the United States: A Comparison With Colon Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:306-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fields AC, Hu FY, Lu P, Irani J, Bleday R, Goldberg JE, Melnitchouk N. Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma: Is There a Difference in Survival for Crohn's Versus Sporadic Cases? J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:303-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kodaira C, Osawa S, Mochizuki C, Sato Y, Nishino M, Yamada T, Takayanagi Y, Takagaki K, Sugimoto K, Kanaoka S, Furuta T, Ikuma M. A case of small bowel adenocarcinoma in a patient with Crohn's disease detected by PET/CT and double-balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1774-1778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lech G, Korcz W, Kowalczyk E, Chaber A, Słodkowski M. The risk of small bowel adenocarcinoma in patients with Crohn's disease. Prz Gastroenterol. 2020;15:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Piton G, Cosnes J, Monnet E, Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Savoye G, Cadiot G, Flourie B, Capelle P, Marteau P, Lemann M, Colombel JF, Khouri E, Bonaz B, Carbonnel F. Risk factors associated with small bowel adenocarcinoma in Crohn's disease: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1730-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhou H, Zhu L, Song J, Wang G, Li P, Li W, Luo P, Sun X, Wu J, Liu Y, Zhu S, Zhang Y. Liquid biopsy at the frontier of detection, prognosis and progression monitoring in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Mauri G, Vitiello PP, Sogari A, Crisafulli G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Marsoni S, Siena S, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsies to monitor and direct cancer treatment in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2022;127:394-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Broccard SP, Kasbi AA, Bagaria SP, Jones J, Shoudry M, Gabriel EM. Liquid biopsies for colorectal cancer: a narrative review of ongoing clinical trials and the current use of this technology at a comprehensive cancer center. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13:438-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Raza A, Khan AQ, Inchakalody VP, Mestiri S, Yoosuf ZSKM, Bedhiafi T, El-Ella DMA, Taib N, Hydrose S, Akbar S, Fernandes Q, Al-Zaidan L, Krishnankutty R, Merhi M, Uddin S, Dermime S. Dynamic liquid biopsy components as predictive and prognostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41:99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhong Y, Ma T, Qiao T, Hu H, Li Z, Luo K, Wang Y, Tang Q, Wang G, Huang R, Wang X. Role of Phenotypes of Circulating Tumor Cells in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:7077-7085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Coco D, Leanza S, Boccoli G. Small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA) three years after colonic adenocarcinoma in an elderly patient: Case report in a National Institute of Health and Aging (INRCA) and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:939-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Ribeiro U Jr. Impact of enteroscopy on diagnosis and management of small bowel tumors. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32:319-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chen WG, Shan GD, Zhang H, Li L, Yue M, Xiang Z, Cheng Y, Wu CJ, Fang Y, Chen LH. Double-balloon enteroscopy in small bowel tumors: a Chinese single-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3665-3671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee SC. Minimally invasive surgery with adenocarcinoma of jejunum diagnosed pathologically before surgery: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;79:354-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Xiao L, Sun L, Zhao K, Pan YS. Crohn's disease with infliximab treatment complicated by rapidly progressing colorectal cancer: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Egea-Valenzuela J, Belchí-Segura E, Essouri N, Sánchez-Torres A, Carballo-Alvarez F. Adenocarcinoma of the rectum and anus in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with infliximab. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:501-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Smaali J, Sekkach Y. Adénocarcinome ano-réctal après traitement par Infliximab pour une maladie de Crohn fistulisante [Anorectal adenocarcinoma after Infliximab treatment for fistulizing Crohn's disease]. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;26:172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |