Published online Mar 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i7.1627

Peer-review started: December 2, 2022

First decision: December 19, 2022

Revised: January 2, 2023

Accepted: February 2, 2023

Article in press: February 2, 2023

Published online: March 6, 2023

Processing time: 91 Days and 10.1 Hours

Prostate lymphoma has no characteristic clinical symptomatology, is often misdiagnosed, and currently, clinical case reports of this disease are relatively rare. The disease develops rapidly and is not sensitive to conventional treatment. A delay in the treatment of hydronephrosis may lead to renal function injury, often causing physical discomfort and rapid deterioration with the disease. This paper presents two patients with lymphoma of prostate origin, followed by a summary of the literature concerning the identification and treatment of such patients.

This paper reports on the cases of two patients with prostate lymphoma admitted to the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, one of whom died of the disease 2 mo after diagnosis, while the other was treated promptly, and his tumor was significantly reduced at the 6-mo follow-up.

The literature shows that prostate lymphoma is often seen as a benign prostate disease during its pathogenesis, even though primary prostate lymphoma enlarges rapidly and diffusely with the invasion of surrounding tissues and organs. In addition, prostate-specific antigen levels are not elevated and are not specific. There are no significant features in single imaging either, but during dynamic observation of imaging, it can be found that the lymphoma is diffusely enlarged locally and that systemic symptoms metastasize rapidly. The two cases of rare prostate lymphoma reported herein provide a reference for clinical decision making, and the authors conclude that early nephrostomy to relieve the obstruction plus chemotherapy is the most convenient and effective treatment option for the patient.

Core Tip: Primary prostate lymphoma is extremely rare clinically. Its common pathological type is non-diffuse large b-cell lymphoma, and the mainstream treatment is chemotherapy. However, its diagnosis lacks specific indicators, and delays in treatment due to clinical misdiagnosis often result in adverse events. Early detection of suspicious lesions and provision of appropriate aggressive treatment, such as rituximab–cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, before the continued expansion of the metastatic area has a positive impact on patient prognosis.

- Citation: Chen TF, Lin WL, Liu WY, Gu CM. Prostate lymphoma with renal obstruction; reflections on diagnosis and treatment: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(7): 1627-1633

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i7/1627.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i7.1627

Lymphoma is a relatively common clinical malignancy with a wide range of lesions, usually originating in the lymph nodes and more rarely in the prostate. Pathologically, lymphomas are divided into Hodgkin’s disease, which is more common, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), which is a heterogeneous malignancy caused by allogeneic B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, or natural killer cells.

Primary prostate lymphoma (PPL) is an extra-nodal lymphoma and is extremely rare, accounting for only 0.09% of prostate tumors and 0.1% of all NHL[1,2]. The majority of cases are NHL, whose main pathological type is diffuse large b-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Due to the rarity of PPL, patients usually seek help from doctors for non-specific low urinary tract symptoms, and the disease is often misdiagnosed because of the lack of recognized symptoms. As a result, the optimal diagnosis and treatment time of patients are delayed, and, to date, only a few cases have been reported in the literature.

This document concerns two patients with prostate lymphoma. One of them is a 41-year-old male patient who experienced a delayed diagnosis, refused further treatment, and died 3 mo later. The other is a 70-year-old male patient who was treated aggressively after diagnosis. His tumor was found to be under control at his 6-mo follow-up. After the two cases are presented, the authors review the literature on prostate lymphoma and summarize the disease characteristics and its treatment.

Case 1: A 41-year-old Chinese male presented to a urology clinic with a complaint of obstruction during urination.

Case 2: A 70-year-old male patient with progressive worsening of urinary frequency and urgency for half a month. The study was approved by the hospital institutional review board and the patient signed an informed consent form.

Case 1: Two weeks before the onset of his symptoms, the patient had been diagnosed as having an intestinal obstruction in the emergency room after suffering constipation. A computed tomography (CT) scan examination revealed an enlarged prostate, so the patient was referred to urology.

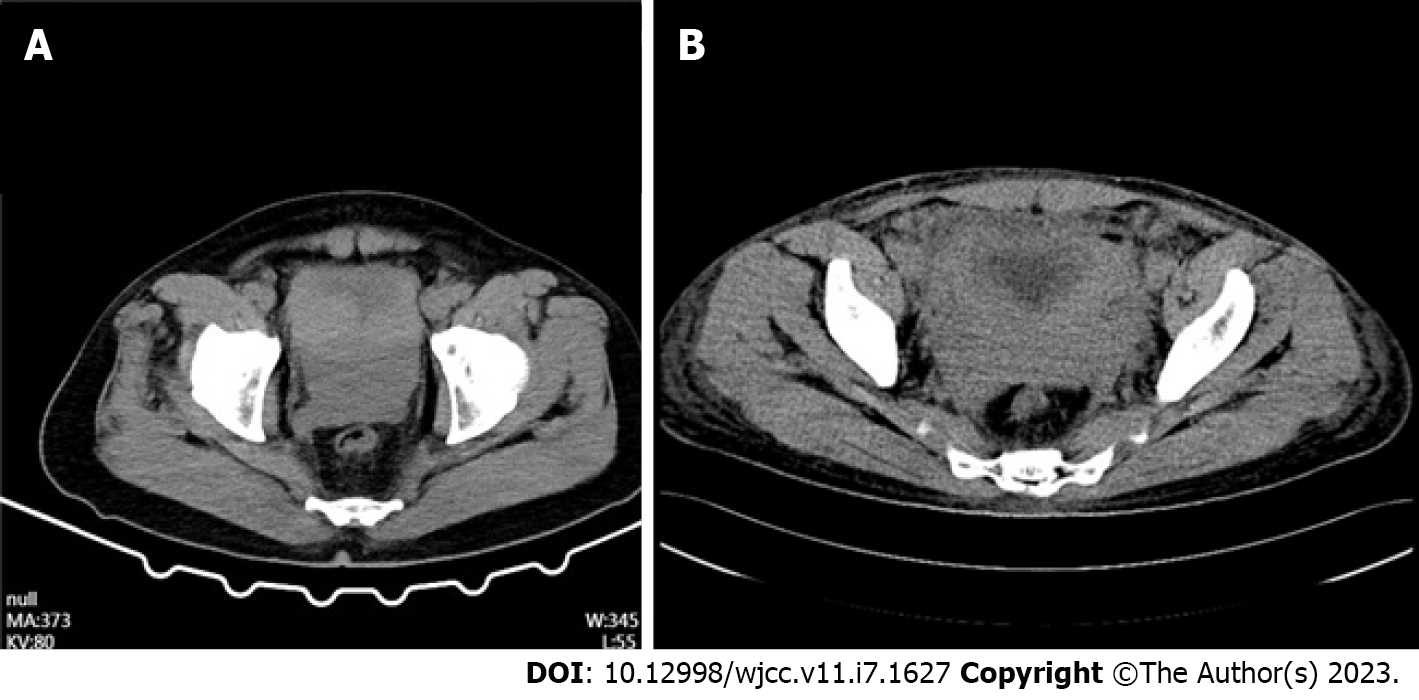

Case 2: Six months later, the patient returned to the hospital with worsening symptoms and constipation. On April 23, 2022, the patient's CT scan (Figure 1A) showed significant bladder wall thickening with prostatic hyperplasia involving bilateral ureteral openings, surrounding fatty infiltration, and multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the pelvis and retroperitoneum with hydronephrosis and hydroureteronephrosis.

Case 1: The patient denied any history of hepatitis, tuberculosis, malaria, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, mental illness, surgery, trauma, blood transfusion, or food or drug allergy.

Case 2: The patient has had a history of hypertension for over 10 years, which is regularly treated and well-controlled.

Neither patient had any family history of malignancy.

Case 1: The results of the physical examination were as follows: temperature 36.5°C; blood pressure 117/68 mmHg; heart rate 82 beats per minute; and respiratory rate 19 breaths per minute. In addition, a rectal examination was performed and the enlarged prostate tissue was palpated. The anal examination did not find any blood and the tissue was soft in texture.

Case 2: No enlarged lymph nodes were palpable throughout the body. Finger examination of the prostate: Enlarged prostate, hard texture, the disappearance of the central sulcus, no tenderness, no nodules palpable, no swelling in the rectum, no blood staining in the finger sleeve.

Case 1: The levels of serum tumor markers were normal (carcinoembryonic antigen, 4.3 ng/mL; carbohydrate antigen 19-9, < 2 U/mL; and alpha-fetoprotein 3.1 ng/mL), and no abnormalities were found in routine blood and urine analyses.

Case 2: Laboratory tests include liver and kidney function tests, electrolytes, tumor markers, coagulation, and routine blood tests. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was 0.58 ng/mL, hemoglobin 108 g/L, red blood cell count 3.69 109/L, platelet count 116 109/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 304 U/L, creatinine 669 umol/L. Bone marrow serology shows no tumor cells. Liquid-based thin-layer cytology + cell tissue examination (urine): a small number of cell clusters with elevated nucleoplasm ratio can be seen microscopically and tumor cells cannot be excluded.

Case 1: The CT scan revealed thickening of the bladder wall, indistinct structure of the bladder-bilateral seminal vesicle-prostate area, and an isointense mass shadow with indistinct demarcation with the adjacent perirectal area, bilateral pelvic wall, and bilateral ureters, with bilateral kidney and bilateral ureteral effusion (Figure 1B). Therefore, a provisional diagnosis of urinary tract obstruction was made.

Case 2: As the disease was progressing very rapidly and had much in common with the previous patient, lymphoma was suspected, and refined magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested a malignant occupying lesion of the prostate involving the bladder, with surrounding fatty infiltration and multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the pelvis and retroperitoneum (Figure 2). The mass extends upwards to the bladder, and the bladder wall is markedly irregularly thickened, up to about 3.2 cm.

Both cases were diagnosed as PPL.

To relieve the obstruction, the patient agreed to undergo a right hemicolectomy and ileostomy and abdominal, pelvic, and bladder tissue biopsies, and postoperative pathology suggested B-cell NHL consistent with DLBCL (of the germinal center subtype).

To verify the nature and origin of the tumor, on May 6, 2022, the patient underwent a transrectal core prostate biopsy and electrosurgery of the bladder mass for pathological biopsy. The immunohistochemistry results a few days later confirmed DLBCL (of the germinal center subtype): CD20 (+), CD79a (+), CD3 (partial +), CK (−), GATA3 (−), P63 (partial weak +), Ki67 (90% +), CD10 (−), Bc1-6 (+), and MUM-1 (+).

After surgery, the patient's creatinine continued to rise and bilateral renal obstruction was considered, so we treated with a double nephrostomy. Patient received R-CHOP first-line chemotherapy under immunohistochemical guidance and based on existing literature and clinical consensus.

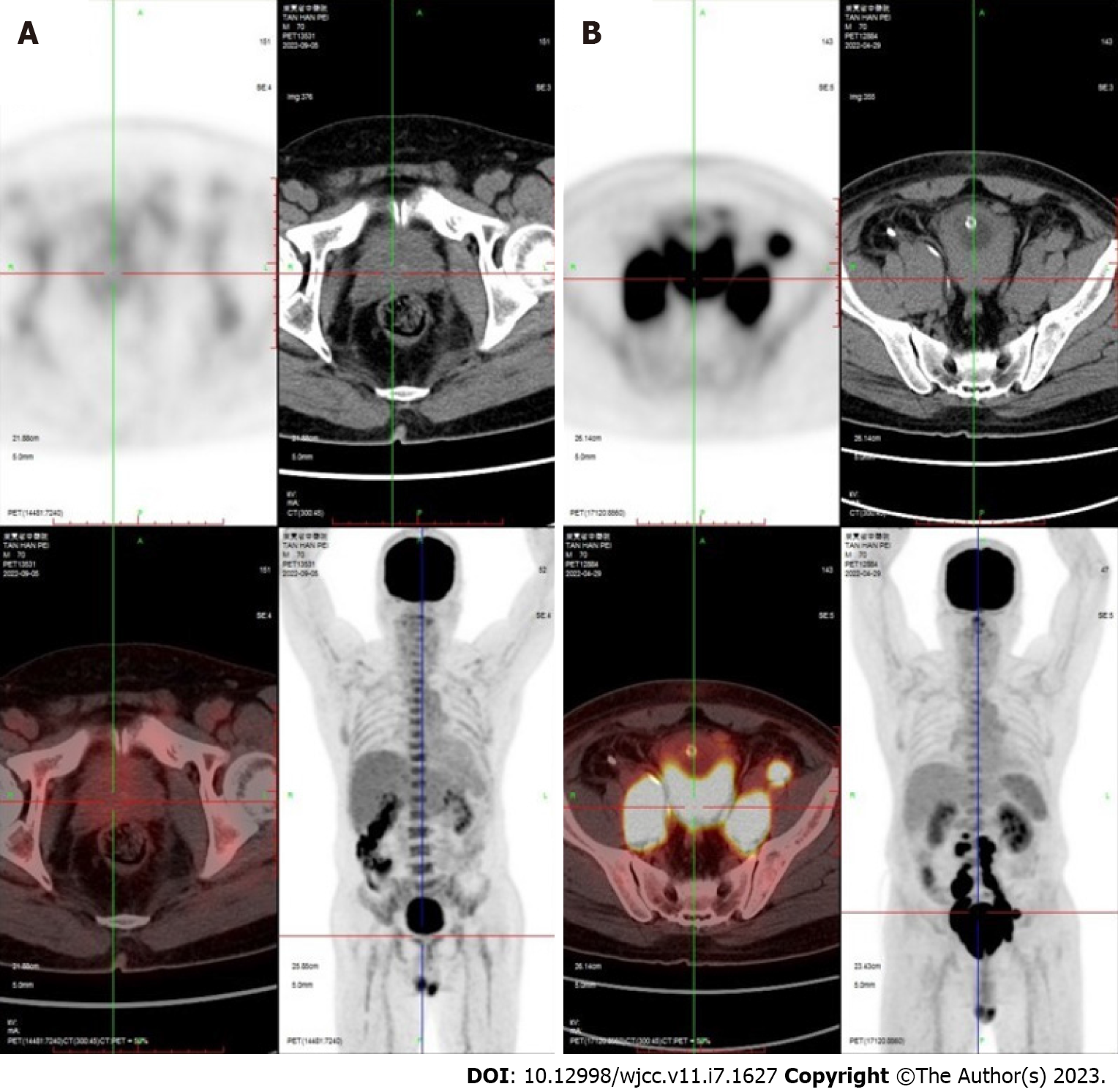

The patient refused any further treatment and died on November 25, 2013 due to disease progression.

The patient later underwent positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, which suggested a malignant prostate tumor with invasion of the bladder and multiple lymph node metastases. The patient was placed on a rituximab–cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy regimen, which was followed up 6 mo later with PET-CT. The scan showed significant tumor shrinkage and no abnormal lymph node invasion (Figure 3).

At present, the patient's kidney function has returned to normal after treatment. The patient did not undergo surgery to remove the tumor, and re-examination showed no signs of tumor progression.

The etiology of DLBCL is unclear, and patients usually present with a rapidly growing tumor in one or more lymph nodes or extra-nodal organs. The clinical diagnosis of the disease currently relies on pathology, and because extra-nodal sources or even prostate sources are extremely rare, most cases are only discovered by accident and often after an alternative diagnosis, which inevitably delays the correct treatment. The current consensus on a diagnosis of PPL is based on the following criteria: (1) The tumor is confined to the surrounding soft tissues; (2) there is no lymph node involvement, and (3) no systemic lymphoma is detected at least 1 mo after the diagnosis of the primary tumor. The prognosis for either primary or secondary lymphoma is poor, with a median survival time of 23 mo after a diagnosis[2].

The clinical presentation of lymphoma depends on the site of the lesion. Lymphoma of the urinary tract usually presents with lower urinary tract symptoms, and it is important to distinguish its diffuse proliferation on imaging from benign prostatic disease. The common clinical signs and symptoms of PPL include dyspareunia, dysuria, frequent and urgent urination, and anal prolapse, and although the lower urinary tract symptoms are similar to those of prostate cancer, the PSA values of PPL are generally 4 ng/mL[3,4], which differentiates it from general prostate cancer.

Rectal palpation is the simplest and most direct method of examining the prostate. The previous literature suggests that most patients with PPL have a diffusely enlarged prostate on rectal palpation, without pressure, with a hard or moderately hard texture and loss of the central groove, with or without a palpable nodular pattern[3,5]. However, the cystoscopic findings of PPL are indistinguishable from prostatic hyperplasia and show a narrowing of the prostatic urethra and, in advanced cases with extensive infiltration, distortion of the urethra, bladder neck, and trigone. The progression of NHL disease is usually accompanied by an increase in LDH, which is significant in patients with diffuse prostatic hyperplasia but normal PSA, suggesting that consideration should be given to there being more subtypes of prostate neoplasia, especially for a differential diagnosis of lymphoma.

Integrating the imaging features of diffuse large B lymphoma of the prostate has been reported in several clinics, and CT/MR imaging of lymphoma of the extra-junctional urinary tissues mostly shows diffuse hyperplasia and heterogeneous masses[6,7]. In addition, MRI has been reported to show mainly equal or slightly low signals on T1-weighted imaging (WI) and slightly high signals on T2WI, which is lower than is the case with other prostate malignancies. Due to the density of the cells within the tumor, diffusion-WI generally shows a significantly high signal and mild to moderate homogeneous delayed enhancement on enhanced scans, and necrotic non-enhancing areas may appear in the center when the tumor is large[8]. These features are consistent with those found in the present case reports.

In cases reported both nationally and internationally, PET-CT is more specific and sensitive for the diagnosis of NHL as it can show hypermetabolic prostatic lesions, and so it can assist in the localization and staging of PPL. PET-CT is therefore recommended for the management and prognosis of this group of patients wherever it is available because it appears to help in the early diagnosis of PPL and can demonstrate the presence of abnormal metabolic foci in other lymph nodes or organs[9,10]. Based on previous reports suggesting that imaging is not yet specific enough for the diagnosis of PPL, the examination of PSA is recommended as an adjunct[11].

The diagnosis of DLBCL usually relies on pathological and immunohistochemical findings for staging. Routine immunohistochemical markers include CD19, CD20, PAX5, CD3, CD5, CD79a, CyclinD1, and Ki-67, which usually show CD19 (+), CD20 (+), PAX5 (+), CD3 (−). Immunohistochemical examination shows that a diffuse expression of CD79a and CD20 in tumor cells is typical of DLBCL. Based on its immunophenotype and gene expression profile, DLBCL can be classified into two types: germinal center-like B cells and non-germinal center-like B cells[12]. Usually, CD3 (+), diffusely expressed as MUM-1, indicates that the tumor cells originate from B cells, while CK (−) suggests non-epithelial malignancy and, in combination with PSA (−), excludes the possibility of prostate cancer. Rituxan is a chimeric monoclonal antibody to CD20, a cell surface protein that is one of the typical features of DLBCL, and it can specifically target the CD20 antigen in B-cell lymphomas, and R-CHOP is considered a first-line chemotherapy regimen[13]. It now appears that the specific choice of chemotherapy regimen should depend on the histological classification[14].

Due to the rarity of prostate lymphoma, its characteristics are still being explored, but the above disease characteristics and differential diagnosis may help clinicians in the evaluation and treatment of prostate lymphoma. Through the above analysis, the authors concluded that patients with abnormal prostate enlargement with urinary tract obstruction or intestinal obstruction and no specific elevation of PSA should be investigated for prostate lymphoma to avoid delaying treatment with an aggressive chemotherapy regimen that will benefit patient survival rates.

In summary, this report describes two rare cases of PPL whose early clinical manifestations are not significantly different from lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. The disease was resistant to conventional drug therapy, with very rapid tumor progression, but early identification increased the patient’s chances of survival.

While the majority of patients report symptoms of discomfort during the progression of the disease, it is often initially diagnosed as urinary tract obstructive disease, and the lack of knowledge of prostate lymphoma means that appropriate treatment is often delayed. Misdiagnosis and delayed treatment are negative predictors of prognosis, but active diagnosis and chemotherapy can relieve the affected symptoms, control the progress of the disease, and improve the prognosis.

The authors thank the Department of Radiology and Pathology of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine for providing the imaging and pathological data.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cassell III AK, Liberia; Syahputra DA, Indonesia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Wang J, Ding W, Gao L, Yao W, Chen M, Zhao S, Liu W, Zhang W. High Frequency of Bone Marrow Involvement in Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:118-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bostwick DG, Iczkowski KA, Amin MB, Discigil G, Osborne B. Malignant lymphoma involving the prostate: report of 62 cases. Cancer. 1998;83:732-738. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Kang JJ, Eaton MS, Ma Y, Streeter O, Kumar P. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and concurrent adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Rare Tumors. 2010;2:e54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang K, Wang N, Sun J, Fan Y, Chen L. Primary prostate lymphoa: A case report and literature review. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2019;33:2058738419863217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bostwick DG, Mann RB. Malignant lymphomas involving the prostate. A study of 13 cases. Cancer. 1985;56:2932-2938. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Hori Y, Nishii M, Masui S, Yoshio Y, Hasegawa Y, Kanda H, Yamada Y, Arima K, Sugimura Y. [A case of primary malignant lymphoma of the prostate with characteristic MRI findings]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2013;59:377-380. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Hu S, Wang Y, Yang L, Yi L, Nian Y. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the prostate with intractable hematuria: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:1187-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. |

Zhou JF, Xia L, Liu CB, Yan WP, Lu DY.

The diagnostic value of multimodal imaging using CT, MRI and 18F-FDG PET-CT for extranodal lymphoma of the abdomen and pelvic. |

| 9. | Ilica AT, Kocacelebi K, Savas R, Ayan A. Imaging of extranodal lymphoma with PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:e127-e138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pan B, Han JK, Wang SC, Xu A. Positron emission tomography/computerized tomography in the evaluation of primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of prostate. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6699-6702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Spencer JA, Golding SJ. Patterns of lymphatic metastases at recurrence of prostate cancer: CT findings. Clin Radiol. 1994;49:404-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, Müller-Hermelink HK, Campo E, Braziel RM, Jaffe ES, Pan Z, Farinha P, Smith LM, Falini B, Banham AH, Rosenwald A, Staudt LM, Connors JM, Armitage JO, Chan WC. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2826] [Cited by in RCA: 3146] [Article Influence: 143.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Taleb A, Ismaili N, Belbaraka R, Bensouda A, Elghissassi I, Elmesbahi O, Droz JP, Errihani H. Primary lymphoma of the prostate treated with rituximab-based chemotherapy: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2009;2:8875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sarris A, Dimopoulos M, Pugh W, Cabanillas F. Primary lymphoma of the prostate: good outcome with doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy. J Urol. 1995;153:1852-1854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |