Published online Feb 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i6.1365

Peer-review started: October 14, 2022

First decision: January 5, 2023

Revised: January 18, 2023

Accepted: February 7, 2023

Article in press: February 7, 2023

Published online: February 26, 2023

Processing time: 133 Days and 0.9 Hours

Endometriosis is a common gynecological disorder that affects women of reproductive age. It is characterized by a cancer-like invasion of the extra-uterine endometrium and exhibits a strong association with ovarian clear cell cancer and endometrioid cancer. Endometriosis-associated fallopian tube endometrioid adenocarcinoma synchronized with endometrial adenocarcinoma was rarely reported.

A 49-year-old woman was referred to our hospital complaining about abnormal vaginal bleeding for three years following unsatisfactory medication. Intraoperative frozen sections unexpectedly unveiled an endometrioid cancer of the left fallopian tube with superficial invasion surrounded by diffuse endometriosis synchronized with endometrioid endometrial cancer.

It was difficult to make a differential diagnosis when confronted with incidental findings of fallopian tube cancer lesions synchronized with endometrial cancer. The key differential diagnosis of primary endometriosis-associated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the fallopian tube from endometrial adenocarcinoma invol

Core Tip: The key to distinguishing primary endometriosis-associated fallopian tube cancer from fallopian tube involvement in endometrial cancer was the pathological identification of malignant transformation in endometriosis-associated fallopian tube tumors.

- Citation: Feng JY, Jiang QP, He H. Endometriosis-associated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the fallopian tube synchronized with endometrial adenocarcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(6): 1365-1371

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i6/1365.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i6.1365

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic, estrogen-dependent, and benign chronic inflammatory disease caused by ectopic endometrial-tissue infiltration with three heterogeneous phenotypes (superficial endometriosis, ovarian endometrioma, and deep infiltrating endometriosis)[1]. Possible causes for endometriosis involve retrograde menstruation, pre-existing endometrial abnormalities, and inflammatory factors[1,2]. There is evidence for endometriosis exhibiting a potential for malignant transformation, and that this change can constitute a precursor lesion of ovarian clear cell cancer and endometrioid cancer[3,4]. However, the mechanism(s) underlying the carcinogenesis of endometriosis requires further elucidation. According to the most recent staging system of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), fallopian tube involvement of endometrial cancer should be staged as FIGO IIIa, while synchronized primary endometrial cancer and primary fallopian cancer should be staged respectively. Under some circumstances, however, it is difficult to make a differential diagnosis, e.g., when confronted with incidental findings of fallopian tube cancer lesions synchronized with endometrial cancer. It was therefore critical to our case to identify the origin of the cancerous lesion, and thus contribute to the determination of cancer stage and post-operative therapeutic options. This report was approved by the hospital ethics committee (approval number: 2022-009).

A 49-year-old woman, gravida 1 and para 0, complained about abnormal vaginal bleeding for three years.

Her last menstrual period had been 2019-2-19, and her bleeding during it was slight, irregular, and intermittent. Bleeding began during the menstrual interval and lasted for a short period without other concomitant symptoms. She was prescribed 10 mg of dydrogesterone twice a day for 10–14 days to relieve symptoms for a few months, but the results were unsatisfactory. Transvaginal sonography indicated a 22.0-mm thick endometrium with a non-homogeneous echo pattern, and further diagnostic curettage was then performed. The pathology report ultimately identified local, atypical complex hyperplasia of the endometrium.

There was no other illness in previous medical history.

We noted no exceptional other personal and family history.

Physical examination showed that her BMI was 27.89 kg/m2 (weight, 67 kg; height, 155 cm), and bimanual palpation showed an active and painless mass of approximately 40.0 mm at the left adnexa with no other positive findings.

Laboratory tests indicated a hemoglobin level of 117 g/L (range, 115–150), and some serum tumor markers were unremarkable: CA125 of 17.0 u/mL (range, 0–47), CA153 of 7.2 U/mL (range, 0–20), CA199 of 15.51 U/mL (range, 0–43); however, HE4 (110.4 pmol/L; range, 29.3–68.5) was slightly increased. Liver, kidney, and coagulation functions were negative, and the liquid-based cytology and high-risk HPV tests were negative.

Transvaginal ultrasonography revealed a uterine volume of 63.0 mm × 51.0 mm × 58.0 mm, a mixed lesion (33.0 mm × 14.0 mm) with a non-homogeneous echo in the uterine cavity, and a solid cystic mass (50.0 mm × 29.0 mm) of the left adnexa (Figure 1A-C).

A pathological review at our hospital suggested that the mass of the uterine cavity was a local, atypical, and complex endometrial hyperplastic lesion.

The patient had no desire to preserve her uterus and a malignant endometrial lesion had not been completely excluded within the context of a local, atypical, and complex endometrial hyperplastic lesion. After completing the preoperative examination to exclude operative contraindications, laparoscopic surgery was scheduled with full informed consent. Surgical exploration displayed a distorted and thickened left hydrosalpinx (50.0 mm × 40.0 mm) with a blocked end (Figure 2A). When we viewed the serous-membrane surface of the left fallopian tube we observed no suspected lesions, and we also suspected there were none in the left ovary, right adnexa, or the surface of the uterine body. Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were then performed. We thus uncovered incidental cauliflower lesions and fish-like exogenous lesions filled with a feculent liquid in the left tube by sectioning the lesions intraoperatively (Figure 2B) and found an ulcerous lesion of the endometrium (20.0 mm × 10.0 mm) in the left uterine horn (Figure 2C). Frozen sections unexpectedly unveiled a left fallopian tube endometrioid cancer with superficial myometrial invasion surrounded by diffuse endometriosis synchronized with endometrioid endometrial cancer. We then implemented complete staging surgery, including bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy.

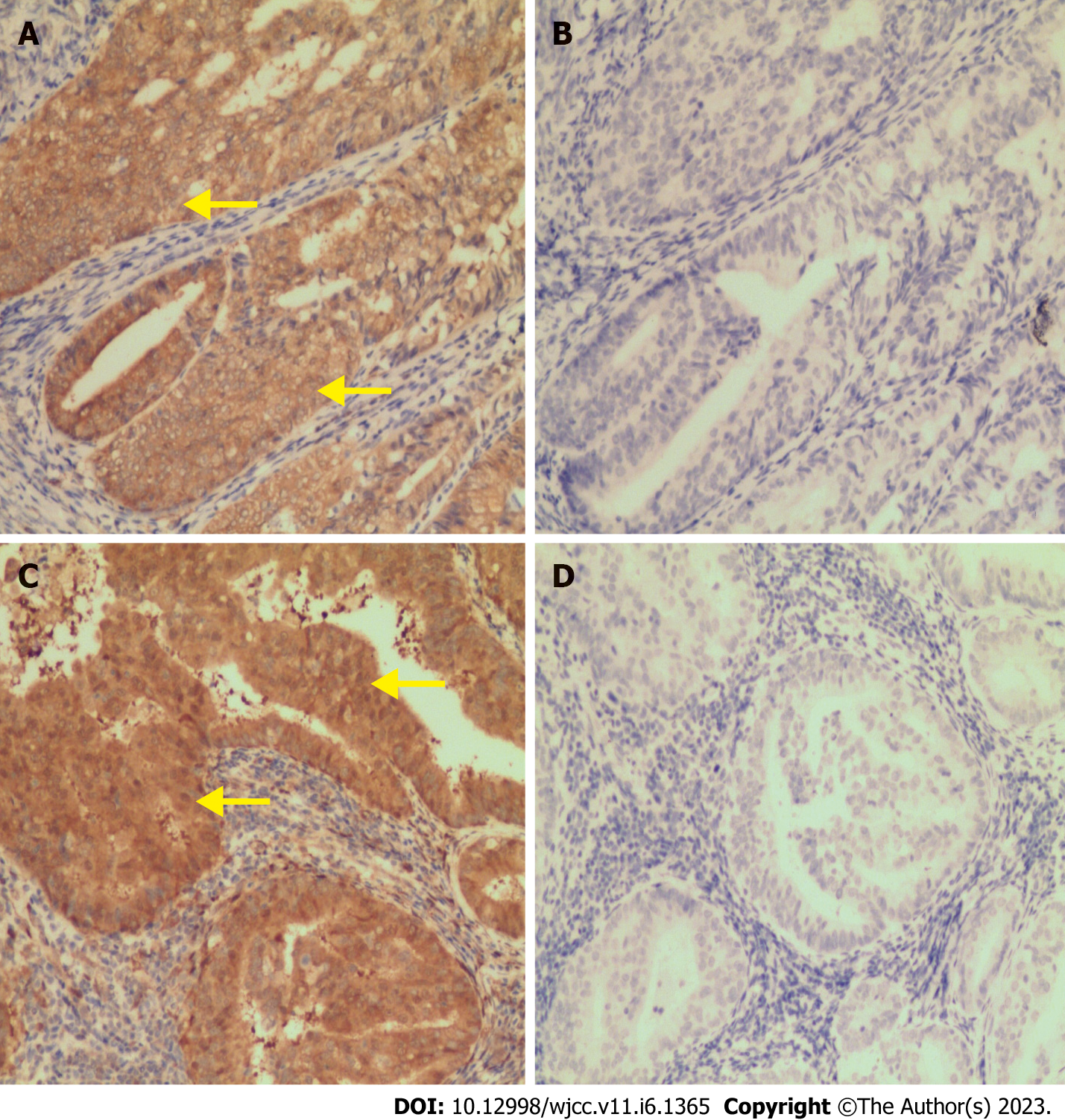

Final paraffin pathology confirmed a well-differentiated endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EEA) derived from the uterine fundus with myometrial invasion of less than 50% (Figure 2D), positive left parametrial metastasis, and negative lymphovascular space involvement or pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenopathy. We also simultaneously diagnosed an endometriosis-associated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the left fallopian tube (Figure 2E) and detected a transitional area from the endometriosis to the atypical hyperplasia to endometrioid adenocarcinoma in the left fallopian tube (shown in Figure 2F, 2G, and 2H). These two cancerous lesions also shared similar expression patterns for ER-α, PR, P53, Ki-67, PTEN (Figure 3A and 3C), PAX2 (Figure 3B and 3D), WT-1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 upon immunohistochemical examination.

After discussion by a multi-disciplinary team, we concluded it was a simultaneous FIGO I stage endometriosis-associated fallopian tube endometrioid adenocarcinoma and FIGO IIIb stage EEA.

Since a high-risk clinicopathological factor–positive left parametrial metastasis was identified, postoperative adjuvant pelvic external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy were prescribed.

Postoperative routine follow-up was performed. The results of postoperative dynamic HE-4 examination, vaginal stump cytology, and pelvic and abdominal sonography were negative. There was no evidence of recurrence in the subsequent three years.

Endometriosis is a condition in which functional endometrial tissue is present outside the uterus, and it is associated with an increased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer[5]. Endometriosis is often confined to the pelvic cavity and principally involves the ovary, ovarian ligaments, cul-de-sac, and uterovesicular peritoneum; however, with a preoperative diagnosis of endometriosis in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, the incidence of fallopian tube endometriosis was 3.8%–12% macroscopically and 37.4–42.5% microscopically[6]. The most common histological subtype of malignant transformation in endometriosis is clear cell cancer, followed by endometrioid adenocarcinoma[7], with age-adjusted incidence ratios of 2.29 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.24–4.20] for ovarian clear-cell cancer and 2.56 (95%CI: 1.47–4.47) for endometrioid ovarian cancer[8]. Importantly, the incidence of microscopic fallopian tube endometriosis among patients with histologically diagnosed endometriosis was significantly higher than in those manifesting macroscopic disease (42% vs 11%–12%, respectively)[6]. Ectopic endometriotic lesions are, in theory, estrogen-dependent and can invade the stroma, demonstrating their potential for malignant transformation. However, the prognostic impact of endometriosis on endometriosis-associated cancers is elusive[7,9,10].

In this case, we first noted the marked evolutionary malignant transformation from fallopian tube endometriosis to atypical hyperplasia to endometrioid adenocarcinoma. We hypothesized that the stimuli required to promote the malignant transformation were non-ovarian-derived estrogen biosynthesized from adipose tissue via the steroid hormone metabolic pathway within an overweight background in our patient. The ectopic endometriotic lesions in the fallopian tube were obstructed by the blocked end of the fimbriae to be disseminated into the pelvic cavity, then they invaded the tubal myometrium, and were ultimately stimulated by estrogen to promote tumorigenesis. The endometrium was also similarly and persistently induced by estrogen to ultimately initialize carcinogenesis.

Second, according to the algorithms of Scully et al[11], the fallopian tube endometrioid adenocarcinoma with superficial myometrial infiltration was surrounded by atypical hyperplasia upon an endometriotic background, while the EEA showed less than 50% myometrial invasion without lymphovascular invasion or distant metastasis. Third, tumor biomarkers such as CA125, CA153, and CA199 were unremarkable, while only HE4 was slightly elevated, which was inconsistent with endometrial cancer accompanied by fallopian tube metastasis. These pathological and clinical characteristics supported both fallopian tube and endometrial cancer occurring independently. We consequently proposed that the tumorigenesis in both the fallopian tube and endometrium was contemporaneous.

In clinical practice, making a differential diagnosis of concurrent primary cancer of the fallopian tube and endometrium from fallopian metastasis of endometrial cancer, which involves post-adjuvant treatment decisions and oncologic outcomes, is challenging. Using Scully algorithms, we might be able to make a proper differential diagnosis when confronted with concurrent cancers derived from multiple sites of the female genital tract. In this case report, we demonstrated a concurrent endometriosis-associated endometrioid cancer of the fallopian tube and primary endometrial cancer in a premenopausal woman. Fortunately, the pathological identification of malignant transformation in the fallopian endometriosis lesion led to distinct differentiation from primary endometrial cancer dissemination.

The authors thank the patient for providing consent to publish this case report.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aniţei MG, Romania; Hegazy AA, Egypt S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Chapron C, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Santulli P. Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:666-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 97.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:261-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 948] [Cited by in RCA: 1251] [Article Influence: 113.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dahiya A, Sebastian A, Thomas A, George R, Thomas V, Peedicayil A. Endometriosis and malignancy: The intriguing relationship. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;155:72-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hermens M, van Altena AM, Bulten J, van Vliet HAAM, Siebers AG, Bekkers RLM. Increased incidence of ovarian cancer in both endometriosis and adenomyosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162:735-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kalaitzopoulos DR, Mitsopoulou A, Iliopoulou SM, Daniilidis A, Samartzis EP, Economopoulos KP. Association between endometriosis and gynecological cancers: a critical review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:355-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McGuinness B, Nezhat F, Ursillo L, Akerman M, Vintzileos W, White M. Fallopian tube endometriosis in women undergoing operative video laparoscopy and its clinical implications. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1040-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Capmas P, Suarthana E, Tulandi T. Further evidence that endometriosis is related to tubal and ovarian cancers: A study of 271,444 inpatient women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;260:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hermens M, van Altena AM, Nieboer TE, Schoot BC, van Vliet HAAM, Siebers AG, Bekkers RLM. Incidence of endometrioid and clear-cell ovarian cancer in histological proven endometriosis: the ENOCA population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:107.e1-107.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Charatsingha R, Hanamornroongruang S, Benjapibal M, Therasakvichya S, Jaishuen A, Chaopotong P, Srichaikul P, Jareemit N. Comparison of surgical and oncologic outcomes in patients with clear cell ovarian carcinoma associated with and without endometriosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;304:1569-1576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu G, Wang Y, Chen Y, Ren F. Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis: A systematic review of the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;264:363-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Scully RE, Young Rh. Metastatic tumor of ovary. In: Kurman RJ, editors. Blaustein’s gynecologic pathology of the female genital tract [M] 3rd. New York: Springer 1991; 742. |