Published online Jun 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i16.3830

Peer-review started: January 7, 2023

First decision: March 10, 2023

Revised: March 16, 2023

Accepted: April 12, 2023

Article in press: April 12, 2023

Published online: June 6, 2023

Processing time: 146 Days and 7.6 Hours

Prevotella oris-induced meningitis and Prevotella oris-induced meningitis concomitant with spinal canal infection are extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, only 1 case of Prevotella oris-induced central system infection has been reported. This is the second report on meningitis combined with spinal canal infection due to Prevotella oris.

We report a case of a 9-year-old boy suffering from meningitis and spinal canal infection. The patient presented to the neurosurgery department with lumbo

This report shed light on the characteristics of Prevotella oris infection and highlighted the role of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in pathogen detection.

Core Tip:Prevotella oris is an anaerobic, Gram-negative, nonpigmented bacterium that rarely results in central nervous system infection. To date, only 1 case has been reported of Prevotella oris causing central nervous system infection. We report a patient who suffered from meningitis and spinal canal infection due to Prevotella oris. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing identified the pathogen, although the cerebrospinal fluid and blood cultures were negative. Early detection of pathogens is crucial for patient survival and prognosis. We analyzed the characteristics of Prevotella oris-induced infection and found that all patients were male; the most commonly used antimicrobial agent was metronidazole.

- Citation: Zhang WW, Ai C, Mao CT, Liu DK, Guo Y. Prevotella oris-caused meningitis and spinal canal infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(16): 3830-3836

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i16/3830.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i16.3830

Bacterial meningitis and spinal canal infection are not common but can be deadly. They may result in permanent disabilities such as cognitive impairment and learning disabilities, which pose a threat to public health[1,2]. The leading pathogens of bacterial meningitis and spinal canal infection are mainly Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis[3]. Prevotella oris is rarely the cause of meningitis and spinal canal infections. There was only one documented case of cervical spinal epidural abscess and meningitis caused by Prevotella oris and Peptostreptococcus micros[4]. More references are warranted to understand the characteristics of Prevotella oris-induced central nervous system (CNS) infection. We presented a case of a 9-year-old male with Prevotella oris-induced meningitis and spinal canal infection whose symptoms were relieved significantly after targeted antimicrobial therapy.

A 9-year-old Chinese male presented to the neurosurgery clinic with a complaint of headache and vomiting for 1 d.

The patient had lumbosacral pain for 1 mo prior to this presentation.

Three months prior to admission, the patient presented with fever, otalgia and pharyngalgia and was admitted to a local hospital with a diagnosis of otitis media. He was treated with cephalosporin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (the specific agents and dosages are unknown), and the symptoms were alleviated temporarily. One month later, he had a fever and bilateral muscle pain in the thighs. The pain spread to the whole lumbosacral region. He began to vomit and experienced a progressive headache.

The patient’s personal and family history were not significant.

Physical examination showed that his body temperature was 38 °C, pulse rate was 110 beats per min, respiratory rate was 19 breaths per min and blood pressure was 120/62 mmHg. His consciousness was clear but exhibited despondency. Neurological examinations revealed that his meningeal irritation sign was negative and other functions were normal.

A routine blood examination revealed 12990 leukocytes/µL (79% neutrophils) and procalcitonin was 0.099 ng/mL. The cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) was colorless and clear, and the leukocyte count was 985 cells/µL with 89% polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The CSF glucose was 2.33 mmol/L, the CSF chloride was 114 mmol/L, and the total protein was 962 mg/L. The CSF and blood cultures were negative.

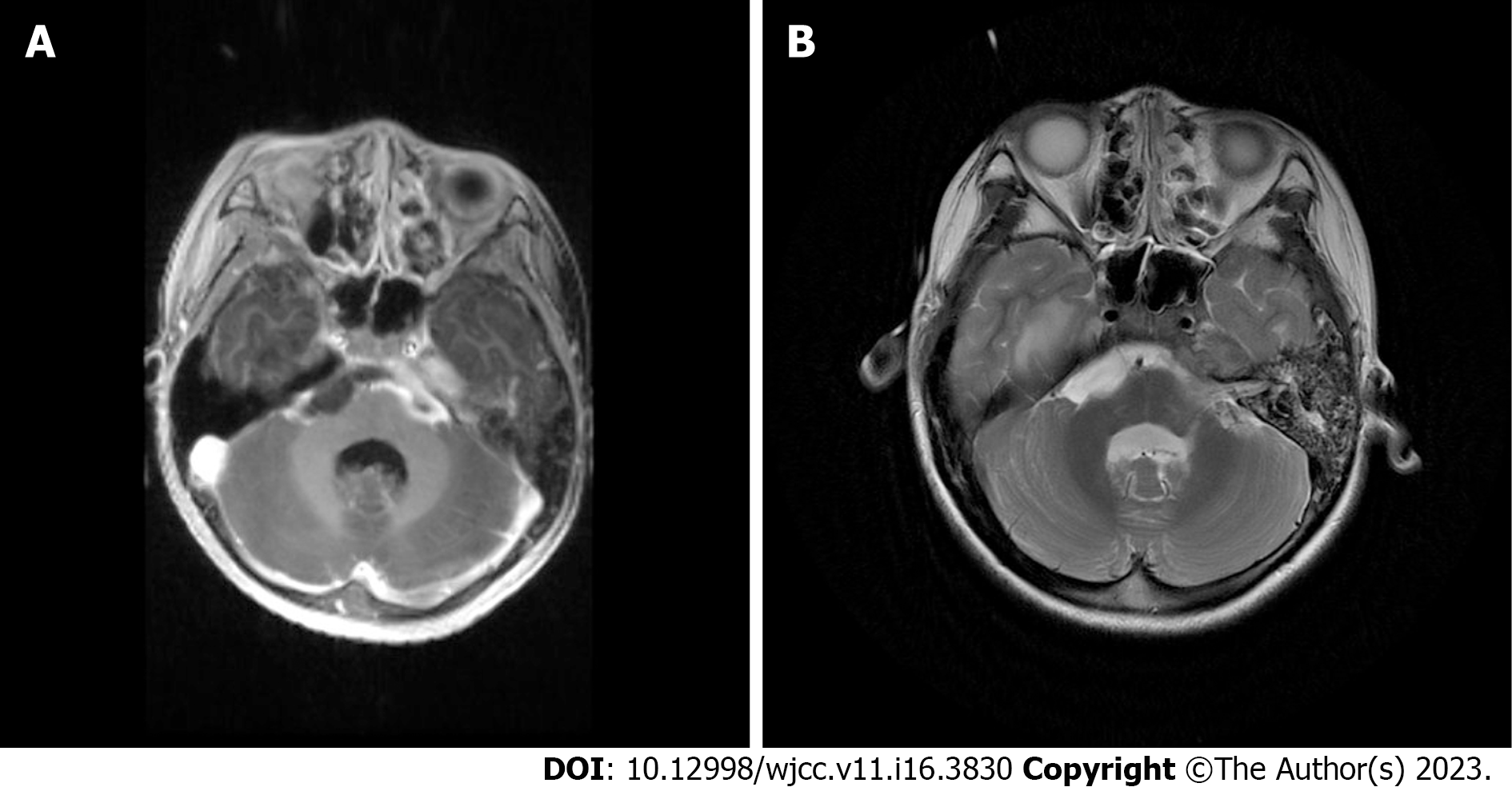

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed hydrocephalus, and there were multiple intracranial meningeal thickening areas and mastoiditis on the left side (Figure 1). In addition, spinal MRI showed that the dura in the thoracolumbosacral spinal canal (mainly in the lumbar segment) was unevenly thickened, and there were scattered small nodular hypointense foci in the spinal canal at the level of the L3-S1 vertebral body, with the largest being approximately 5 mm (Figure 2).

To investigate the pathogenic microorganisms, a CSF specimen was tested using metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS). The results showed the presence of Prevotella oris with a sequence number of 630 copies and a relative abundance of 1.81%.

The patient was diagnosed with meningitis and L3-S1 lumbosacral dural sac infection.

Initially, the patient was empirically treated with intravenous vancomycin (40 mg/kg/d in two divided doses) and meropenem (40 mg/kg every 8 h). He also underwent a puncture and external drainage of the right ventricle and was given intracranial pressure-decreasing agents and systemic nutritional support. His symptoms did not improve. After the mNGS results indicated the presence of Prevotella oris, antibiotic therapy was changed to intravenous metronidazole (15 mg/kg every 6 h) and meropenem (40 mg/kg every 8 h) for 2 wk, followed by meropenem (40 mg/kg every 8 h) for another 2 mo due to the patient experiencing a metronidazole-induced gastrointestinal reaction.

The patient’s temperature returned to normal, and his symptoms improved significantly with targeted antimicrobial therapy. After 1 mo of treatment, the routine blood examination showed that the leukocyte count and the percentage of neutrophil granulocytes returned to normal. The leukocyte count in the CSF was 66 cells/µL with 33% polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The CSF glucose was 3.11 mmol/L, the CSF chloride was 117 mmol/L, and the total protein was 560 mg/L. Brain and spinal MRI showed that the thickening of the intracranial and lumbosacral dura mater was greatly resolved. The ventricular drainage catheter was pulled out. The patient was continuously treated for another month and followed up for 2 mo without recurrence.

CNS infections are potentially devastating and disabling infectious diseases worldwide. They include meningitis, encephalitis, spinal and cranial abscesses, discitis and other complications. It is estimated that the global incidence of CNS infections was 389/100000 between 1990 and 2016[5]. Although CNS infections are not common in developed countries, they remain a public health problem in developing countries[5,6]. Bacterial infections are one type of CNS infection and can be frequently caused by Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Group B strep and Listeria monocytogenes in children[7].

Prevotella oris, a nonpigmented, anaerobic, Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium, is a periodontopathogen and frequently detected in periodontal diseases[8]. We retrieved and reviewed previous cases of Prevotella oris causing extraoral infection from the PubMed database (Table 1). Prevotella oris was reported as a pathogen in pleural infection, bacteremia, hepatic abscess, pericarditis, mediastinitis, sepsis and empyema. Only 1 case reported cervical spinal epidural abscess and meningitis due to Prevotella oris and Peptostreptococcus micros after retropharyngeal surgery in 2004[4]. Upon review, we found that the patients all reported cases were male, and 2 of the 7 cases were initially diagnosed as a tuberculosis infection, which indicated that the symptoms of Prevotella oris-induced infection may not be specific and may be similar to tuberculosis infection.

| Ref. | Age/Sex | Initial symptoms | Infection site | Pathogens | Initial diagnosis | Final diagnosis | Antimicrobial treatment | Outcome |

| Viswanath et al[14], 2022 | 51/M | Right-sided chest pain | Pleura | Prevotella oris | Pulmonary tuberculosis | Pleural infection | Metronidazole (500 mg) IV twice a day initially and then continued for 5 d | Improved |

| Cobo et al[15], 2022 | 70/M | Fever, dyspnea and general malaise | Blood and liver | Prevotella oris | COVID-19 infection | Bacteremia, hepatic abscess | Initially, piperacillin-tazobactam (1 g/8 h/IV) and levofloxacin (500 mg/12 h/IV); subsequently, piperacillin-tazobactam (1 g/8 h/IV) and metronidazole (500 mg/8 h/IV) for 10 d | Recovered |

| Carmack et al[16], 2021 | 34/M | Cough, fever and night sweats | Pericardium | Prevotella oris and Fusobacterium nucleatum | Tuberculosis pericarditis | Pericarditis secondary to Prevotella oris and Fusobacterium nucleatum | Initially, rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol (RIPE) and prednisone, then ceftriaxone and doxycycline; subsequently, ampicillin/sulbactam 3 g every 6 h | Improved |

| Duan et al[17], 2021 | 64/M | Unconsciousness, dyspnea and swelling in the mandible and neck | Mediastinum | Prevotella oris; Prevotella denticola; Streptococcus anginosus; Peptostreptococcus stomatis; Fusobacterium nucleatum; Alloprevotella tannerae | Acute purulent mediastinitis | Descending necrotizing mediastinitis | Initially, vancomycin, imipenem; subsequently, piperacillin/tazobactam and tinidazole; finally, levaquin and piperacillin/tazobactam | Improved |

| Bein et al[18], 2003 | NA | Acute unconsciousness due to spontaneous intracerebral bleeding in the cerebellar region | Blood | Prevotella oris | Spontaneous intracerebral bleeding | Bacteremia and sepsis due to Prevotella oris from dentoalveolar abscesses | Initially, imipenem via central venous catheter; subsequently, metronidazole IV | Improved |

| Abufaied et al[19], 2020 | 42/M | Left-sided pleuritic chest pain and acute onset of left upper limb weakness | Chest | Prevotella oris | Empyema necessitans | Empyema necessitans | 14 d of IV ertapenem and later 14 d of oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg two times daily and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 625 mg three times daily at the time of discharge | Improved |

| Frat et al[4], 2004 | 61/M | Right hemiparesis and bilateral Babinski’s sign | Cervical spinal epidural space and meninges | Prevotella oris and Peptostreptococcus micros | Meningoencephalitis | Cervical spinal epidural abscess and meningitis | Initially, ceftriaxone, amoxicillin and cotrimoxazole; subsequently, fosfomycine, ceftriaxone and metronidazole for 3 wk, followed by 8 wk of oral metronidazole | Improved |

In this case, the patient did not show significant meningitis or spinal infection symptoms. His meningeal irritation sign was negative, and the glucose level of the CSF was in the normal range. Both his blood and CSF cultures were negative. All these factors make pathogen identification more difficult. To investigate the pathogen, we used mNGS, a promising and clinically validated test for CNS infections[9].

Traditional blood and CSF bacterial cultures are essential laboratory tests in meningitis and spinal canal infection. They rarely detect pathogens effectively and in a timely manner under certain circumstances, such as infections caused by oral flora[10]. Compared to traditional methods, mNGS can improve the detection of pathogens to aid clinicians with a timely diagnosis. Some researchers have validated the effects of mNGS in CNS infections[11,12]. It can also provide guidance for clinicians in choosing appropriate antimicrobial regimens.

To date, antimicrobial treatment recommendations have been lacking for Prevotella oris-induced nervous system infection. By reviewing previous case reports, we found that the most commonly used antibiotic for treating Prevotella oris-induced infection was metronidazole, while other antibiotics included piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin/sulbactam, levaquin, ertapenem, ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone. For the documented Prevotella oris-induced and Peptostreptococcus micros-induced cervical spinal epidural abscess and meningitis cases, fosfomycin, ceftriaxone and metronidazole were used for targeted therapy (Table 1). According to the European Committee of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing guidelines, Prevotella oris was susceptible to metronidazole, imipenem, chloramphenicol and cefoxitin discs[13]. For this patient, we used metronidazole and meropenem to treat the infection after we found that the effect of empirical antimicrobial therapy was unsatisfactory. The infection was controlled in a timely and effective manner.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the second report of meningitis combined with spinal canal infection due to Prevotella oris. Despite its rareness, Prevotella oris may cause meningitis and spinal canal infection. The symptoms of this kind of infection may not be typical, and conventional culture tests have difficulty detecting pathogens. mNGS is a promising technique to identify pathogens under such circumstances. Clinicians should be aware of this possibility and treat it with rapid imaging, neurosurgical intervention and targeted antibiotics.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Beran RG, Australia; Mora DJ, Brazil; S-Editor: Liu XF L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Sunwoo JS, Shin HR, Lee HS, Moon J, Lee ST, Jung KH, Park KI, Jung KY, Kim M, Lee SK, Chu K. A hospital-based study on etiology and prognosis of bacterial meningitis in adults. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, Weisfelt M, Reitsma JB, Vermeulen M. Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1849-1859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1049] [Cited by in RCA: 954] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oordt-Speets AM, Bolijn R, van Hoorn RC, Bhavsar A, Kyaw MH. Global etiology of bacterial meningitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0198772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Frat JP, Godet C, Grollier G, Blanc JL, Robert R. Cervical spinal epidural abscess and meningitis due to Prevotella oris and Peptostreptococcus micros after retropharyngeal surgery. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Robertson FC, Lepard JR, Mekary RA, Davis MC, Yunusa I, Gormley WB, Baticulon RE, Mahmud MR, Misra BK, Rattani A, Dewan MC, Park KB. Epidemiology of central nervous system infectious diseases: a meta-analysis and systematic review with implications for neurosurgeons worldwide. J Neurosurg. 2018;1-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sarrazin J-L, Bonneville F, Martin-Blondel G. Infections cérébrales. Journal de Radiologie Diagnostique et Interventionnelle. 2012;93:503-20. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Alamarat Z, Hasbun R. Management of Acute Bacterial Meningitis in Children. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:4077-4089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yousefi-Mashouf R, Duerden B, Eley A, Rawlinson A, Goodwin L. Incidence and distribution of non-pigmented Prevotella species in periodontal pockets before and after periodontal therapy. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1993;6:35-42. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ramachandran PS, Wilson MR. Metagenomics for neurological infections - expanding our imagination. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:547-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xue H, Wang XH, Shi L, Wei Q, Zhang YM, Yang HF. Dental focal infection-induced ventricular and spinal canal empyema: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3114-3121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lan ZW, Xiao MJ, Guan YL, Zhan YJ, Tang XQ. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes in a patient with meningoencephalitis using next-generation sequencing: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ramchandar N, Coufal NG, Warden AS, Briggs B, Schwarz T, Stinnett R, Xie H, Schlaberg R, Foley J, Clarke C, Waldeman B, Enriquez C, Osborne S, Arrieta A, Salyakina D, Janvier M, Sendi P, Totapally BR, Dimmock D, Farnaes L. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Pathogen Detection and Transcriptomic Analysis in Pediatric Central Nervous System Infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nagy E, Justesen US, Eitel Z, Urbán E; ESCMID Study Group on Anaerobic Infection. Development of EUCAST disk diffusion method for susceptibility testing of the Bacteroides fragilis group isolates. Anaerobe. 2015;31:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Viswanath LS, Gunalan A, Jamir I, S B, S A, K A, Biswas R. Prevotella oris: A lesser known etiological agent of pleural effusion. Anaerobe. 2022;78:102644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cobo F, Pérez-Carrasco V, Pérez-Rosillo MÁ, García-Salcedo JA, Navarro-Marí JM. Bacteremia due to Prevotella oris of probable hepatic origin. Anaerobe. 2022;76:102586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Carmack AE, LaRocco AM, Mathew M, Goldberg HV, Patel DM, Saleeb PG. Subacute Polymicrobial Bacterial Pericarditis Mimicking Tuberculous Pericarditis: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e933684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Duan J, Zhang C, Che X, Fu J, Pang F, Zhao Q, You Z. Detection of aerobe-anaerobe mixed infection by metagenomic next-generation sequencing in an adult suffering from descending necrotizing mediastinitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bein T, Brem J, Schüsselbauer T. Bacteremia and sepsis due to Prevotella oris from dentoalveolar abscesses. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abufaied M, Iqbal P, Yassin MA. A Rare and Challenging Presentation of Empyema Necessitans/Necessitasis Leading to Brachial Plexopathy. Cureus. 2020;12:e8267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |