Published online May 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i14.3304

Peer-review started: January 16, 2023

First decision: March 13, 2023

Revised: March 16, 2023

Accepted: April 10, 2023

Article in press: April 10, 2023

Published online: May 16, 2023

Processing time: 120 Days and 2.7 Hours

Sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare disorder involving inflammation of the mesentery. Its etiology remains unclear, but it is believed to be associated with previous abdominal surgery, trauma, autoimmune disorders, infection, or malignancy. Clinical manifestations of sclerosing mesenteritis are varied and include chronic abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, weight loss, formation of an intra-abdominal mass, bowel obstruction, and chylous ascites. Here, we present a case of idiopathic sclerosing mesenteritis with small bowel volvulus in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome.

A 68-year-old female presented with recurrent small bowel obstruction. Imaging and pathological findings were consistent with sclerosing mesenteritis causing mesenteric and small bowel volvulus. Computed tomography scans also revealed pulmonary embolism, and the patient was started on a high dose of corticosteroid and a therapeutic dose of anticoagulants. The patient subsequently improved clinically and was discharged. The patient was also diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome after a hematological workup.

Sclerosing mesenteritis is a rare condition, and patients with no clear etiology should be considered for treatment with immunosuppressive therapy.

Core Tip: In patients with sclerosing mesenteritis, any condition that causes chronic inflammation of mesenteric tissue should be investigated. Antiphospholipid syndrome may be linked with chronic thrombotic activity that can contribute to chronic ischemia of the mesentery. Patients with uncertain etiology should be considered for treatment with immunosuppressive therapy.

- Citation: Chennavasin P, Gururatsakul M. Idiopathic sclerosing mesenteritis presenting with small bowel volvulus in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(14): 3304-3310

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i14/3304.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i14.3304

Sclerosing mesenteritis is a condition of mesenteric inflammation that causes thickening and fibrosis in the bowel mesentery. The disease is frequently limited to the adipose tissue of the small bowel mesentery and is unlikely to involve the omentum, peritoneum, or mesocolon[1]. Sclerosing mesenteritis was first reported in 1924 as “retractile mesenteritis and/or mesenteric panniculitis”[2]. The incidence of this condition is 0.16%–3.30%[3]. The etiology is still unclear; however, it may be associated with various conditions that cause chronic inflammation, such as previous abdominal surgery, trauma, mesenteric ischemia, cancer, infection, and autoimmune conditions. Sclerosing mesenteritis is more common in Caucasians, with a male-to-female ratio of 2-3:1[3,4]. The characteristics of sclerosing mesenteritis may differ in Asian populations since a previous study showed that 58% of Japanese patients also had mesocolon involvement[5].

Clinical manifestations of sclerosing mesenteritis can vary from asymptomatic to severe abdominal pain. It can cause small bowel obstruction, significant weight loss, and chylothorax in severe cases[6,7]. Computed tomography (CT) scans are the investigation of choice, and clinical diagnosis is made using the Coulier criteria, which are: (1) Presence of a well-defined “mass effect” on neighboring structures; (2) Inhomogeneous higher attenuation of mesenteric fat tissue than adjacent retroperitoneal or mesocolonic fat; (3) Small soft tissue nodes; (4) A hypoattenuated fatty “halo sign”; and (5) The presence of a hyperattenuating pseudocapsule, which may also surround the entire entity[8]. Tissue biopsy is recommended to exclude malignancy and confirm the diagnosis of mesenteric fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and fat necrosis[9].

We present the case of a 68-year-old female with recurrent small bowel volvulus caused by sclerosing mesenteritis who responded well to treatment with a corticosteroid. When further investigations were performed to find the cause of the sclerosing mesenteritis, the patient was also found to have antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

A 68-year-old female presented at the hospital with acute abdominal pain and vomiting that had persisted for 1 d.

The patient developed colicky pain with bilious vomiting 1 d prior to visiting the emergency department. Her abdomen was distended, but there was no fever.

The patient’s medical history showed only hypertension, and there was no previous abdominal surgery or abdominal trauma.

There was no significant personal or family history.

Physical examination revealed generalized abdominal tenderness; however, there was no evidence of peritonitis.

Laboratory examination showed that the patient’s white blood cell count was 5930 cells/µL, and creatinine levels had risen from 0.83 mg/dL to 1.76 mg/dL.

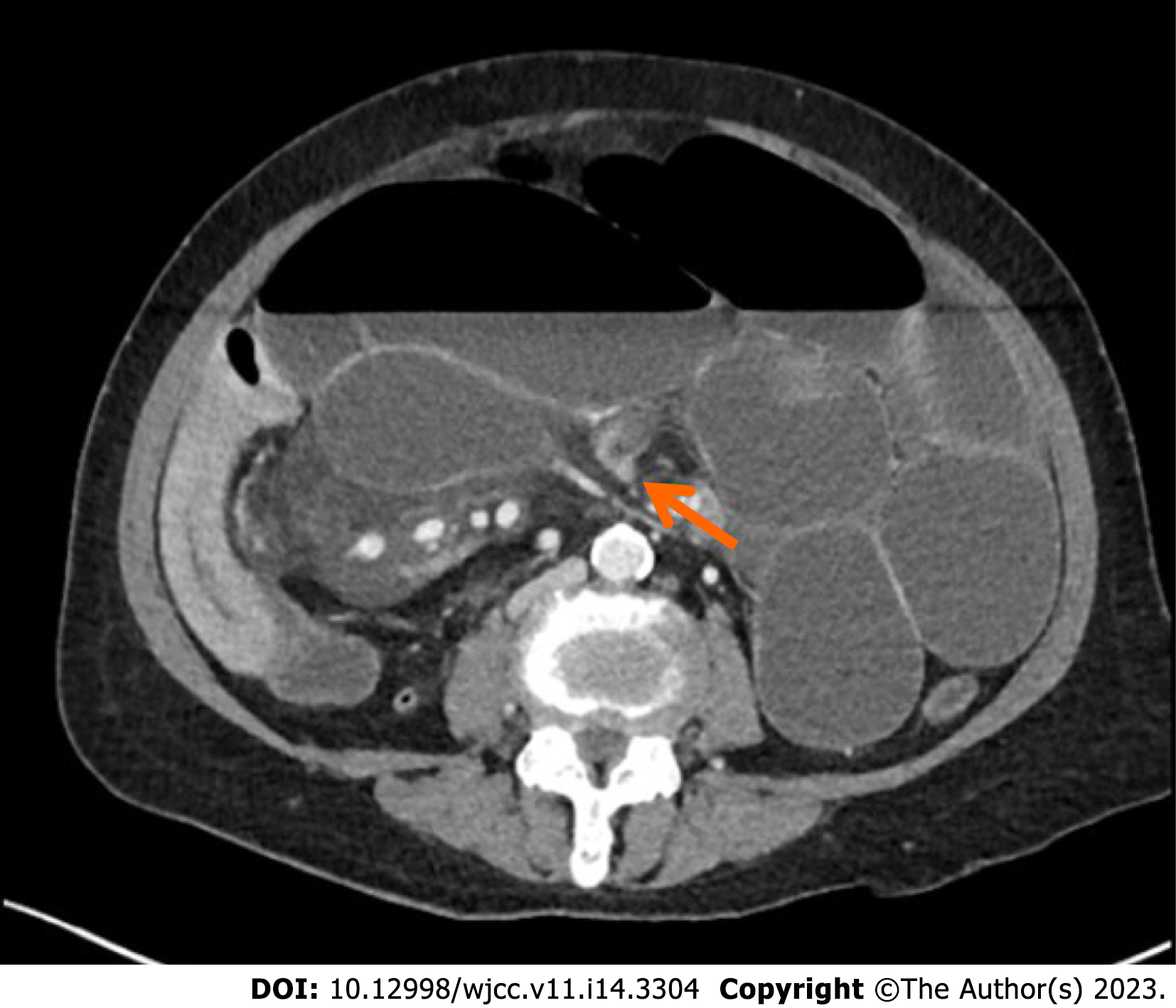

Abdominal X-rays showed generalized small bowel dilatation with air-fluid levels consistent with small bowel obstruction. Therefore, a CT scan of the abdomen was requested. The initial CT scan showed a thickened mesentery around the terminal ileum. At the terminal ileum, there was an abrupt change in caliber caused by rotation with upstream dilatation of the distal jejunum and ileum, consistent with high-grade small bowel obstruction. Misty mesentery and enlargement of mesenteric nodes in the right lower quadrant adjacent to the distal ileum were also observed, possibly secondary to an infection or an inflammatory process (Figure 1).

The patient was given the diagnosis of sclerosing mesenteritis with small bowel obstruction.

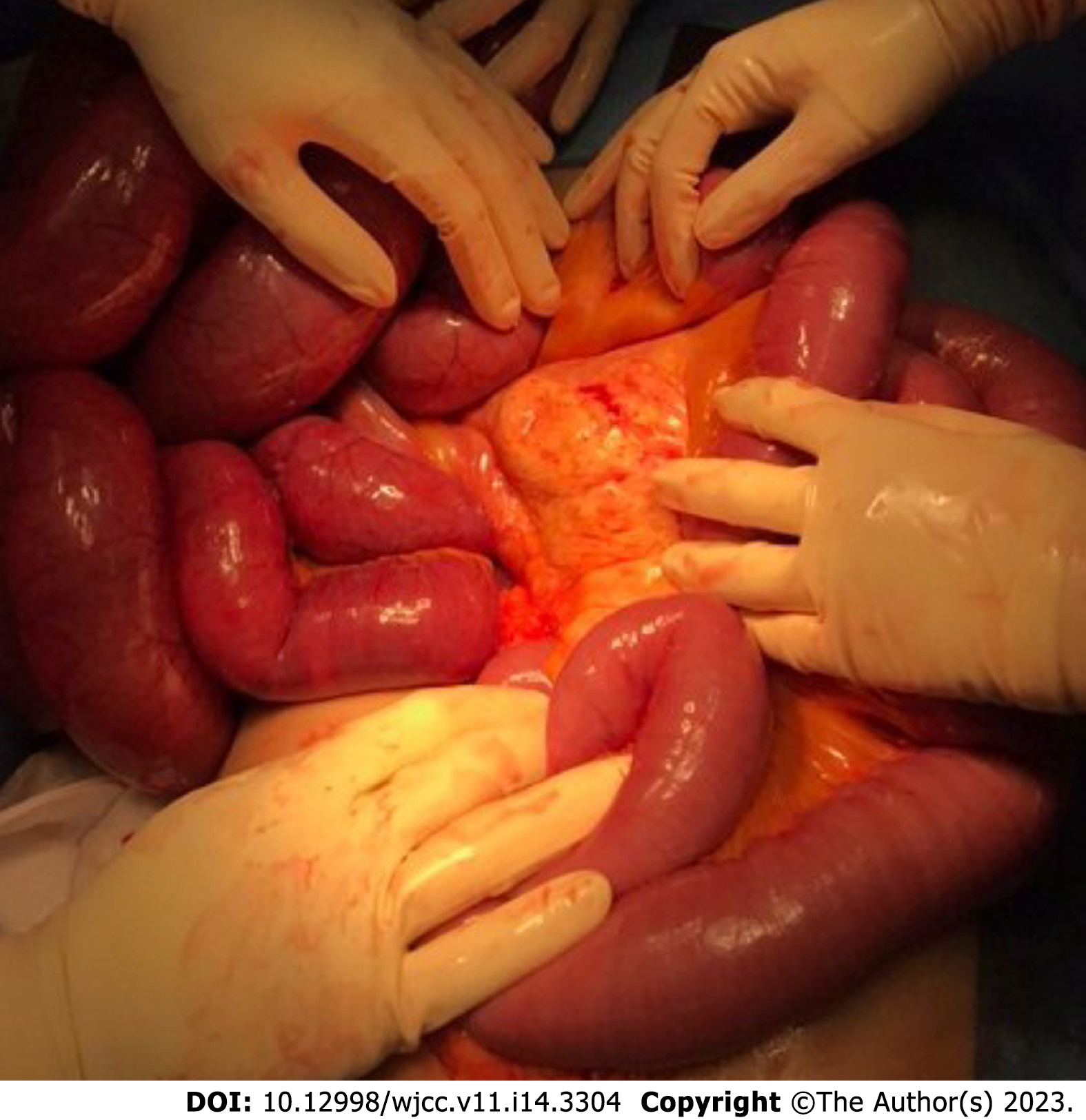

An exploratory laparotomy was performed, which revealed diffuse thickening of the small bowel mesentery causing mesenteric distortion and small bowel volvulus at the level of the terminal ileum with upstream dilatation of the entire small bowel that was associated with significant mesenteric lymphadenopathy. The entire small bowel was viable after small bowel devolvulation was performed. Lymph nodes were also excised for histopathological examination, which subsequently revealed reactive lymph nodes with fat necrosis (Figure 2).

After the operation, the patient’s bowel movements returned to normal. The patient was able to pass stools and tolerated a soft food diet. Further investigations were indicated to exclude occult malignancy, tuberculosis, and other underlying autoimmune conditions. However, while waiting for the results from these investigations, acute abdominal pain with abdominal distension returned on postoperative day 5. Subsequent abdominal X-ray and CT scans showed recurrent small bowel volvulus with the same misty mesentery. A second laparotomy confirmed recurrent small bowel volvulus due to inflammation, and retraction of the small bowel mesentery was observed.

Serology tests showed a positive result for antinuclear antibodies (1:160), which were homogenous with a fine granular cytoplasmic staining pattern, a normal range of IgG4 (0.285 g/L), and negative results for other autoimmune serology and tumor markers (carbohydrate antigen 19-9, alpha fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and cancer antigen 125). Tuberculosis was not found in either tissue histopathology or in the stool. A CT scan of the chest was also performed to exclude tuberculosis or occult malignancy, both of which were negative. However, an incidental small pulmonary embolism was detected. There was no evidence of deep vein thrombosis on Doppler ultrasound of either leg. As a result, further investigation for APS was performed, and tests for anti-beta2-glycoprotein-1 (for all 3 immunoglobulin isotypes: IgA, IgG, and IgM) were found to be positive. Upon a repeat test 3 mo later, the result was still positive (Table 1).

| Blood test | Results |

| Anti-Beta 2-Glycoprotein-1 IgA/IgG/IgM | 38.29 RU/mL |

| Anti-Beta 2-Glycoprotein-1 IgA/IgG/IgM (3 mo later) | 35.69 RU/mL |

| Anticardiolipin IgG | 7.130 U/mL |

| Anticardiolipin IgM | < 2 U/mL |

| ANA | 1:160 |

| ANA 12 specific antigen profile | Negative |

| Serum IgG4 | 0.285 g/L |

| Tissue IgG4 | Negative |

| Lupus anticoagulant | Negative |

| C3 compliment | 0.79 g/L |

| C4 compliment | 0.14 g/L |

| Tissue PCR for mycobacterium tuberculosis | Not detected |

| Stool PCR for mycobacterium tuberculosis | Not detected |

| CEA | 0.9 ng/mL |

| Alpha fetoprotein | 15 ng/mL |

| CA 125 | 30 U/mL |

| CA 19-9 | < 2 U/mL |

After the second operation, the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic sclerosing mesenteritis, and treatment with high-dose corticosteroids and a therapeutic dose of low molecular weight heparin was commenced. The patient responded well to corticosteroids and did not develop further small bowel obstruction or volvulus. In addition, bowel function was normal, a normal diet was tolerated, and the patient was discharged after 2 wk with a weaning dose of oral corticosteroid over an 8-wk period.

At a follow-up appointment 2 mo after discharge, an upper endoscopy and a colonoscopy were performed; the results of which were unremarkable. A repeat anti-beta2-glycoprotein1 (IgA, IgG, and IgM) test at 3 mo was positive, and the patient was diagnosed with APS. As a result, the patient must continue lifelong anticoagulant therapy.

Sclerosing mesenteritis refers to chronic inflammation of the mesentery. This condition is rare and is more common in Caucasian males[4]. In the present case report, the patient was an Asian female without any significant underlying disease and no previous abdominal surgery. Sclerosing mesenteritis was considered to be the rare cause of small bowel obstruction. The CT scan revealed inhomogeneous higher attenuation of mesenteric fat tissue and small soft tissue nodes in the mesentery surrounded by hypoattenuated mesenteric fat, which is consistent with the Coulier criteria[8] for sclerosing mesenteritis. Pathological features also confirmed chronic inflammation of mesenteric fat without evidence of malignancy.

Several studies have reported patients with sclerosing mesenteritis who have small bowel obstruction, and the majority of these cases required surgical intervention to correct the obstruction followed by treatment with an immunosuppressive medication[10-12]. Surgery may be performed to correct gut obstruction, but it is not a curative treatment[13]. Our patient was diagnosed with idiopathic sclerosing mesenteritis. After the first operation was performed, we did not administer any immunosuppressive medication immediately because we were waiting for all the results to exclude other primary causes, including infection and cancer. Subsequently, the patient developed recurrent small bowel volvulus and required a second exploratory operation. The patient responded well to treatment with corticosteroids.

The etiology of sclerosing mesenteritis is unclear; however, it is generally associated with chronic inflammation of mesenteric tissue. This may be caused by previous abdominal surgery, trauma, mesenteric ischemia, cancer, infection, or autoimmune disease[13]. In this case, the patient was also subsequently diagnosed with APS after an incidental finding of pulmonary embolism during the diagnostic workup. Only a few case reports have shown chronic thrombosis-associated chronic mesenteric ischemia. One case report detailed sclerosing mesenteritis with sacroiliitis[14], and another reported sclerosing mesenteritis with Factor V Leiden[15]. Both cases raise the possibility of a link between mesenteric ischemia and chronic thrombotic activity.

Thrombosis can affect vessels of any size in APS patients; however, a gastrointestinal manifestation in APS is uncommon[16]. To date, there has been no reports of a potential association between APS and sclerosing mesenteritis; however, it is thought that chronic venous thrombosis may cause mesenteric ischemia in APS patients[17]. In the case of our patient, it is possible that the small veins in the small bowel mesentery were affected by chronic venous thrombosis causing chronic inflammation that led to sclerosing mesenteritis. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate hypercoagulable states in patients with sclerosing mesenteritis.

Sclerosing mesenteritis is a chronic inflammation of the mesentery that is commonly caused by other medical conditions, including infection, autoimmune conditions, and malignancy. Symptomatic patients with unclear etiology should be considered for treatment with immunosuppressive medications. In addition, while rare, chronic thrombotic conditions can also cause sclerosing mesenteritis, and they should also be considered.

We thank Edanz (www.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Thailand

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gu GL, China; Zharikov YO, Russia S-Editor: Liu XF L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Buragina G, Magenta Biasina A, Carrafiello G. Clinical and radiological features of mesenteric panniculitis: a critical overview. Acta Biomed. 2019;90:411-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Green MS, Chhabra R, Goyal H. Sclerosing mesenteritis: a comprehensive clinical review. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Protin-Catteau L, Thiéfin G, Barbe C, Jolly D, Soyer P, Hoeffel C. Mesenteric panniculitis: review of consecutive abdominal MDCT examinations with a matched-pair analysis. Acta Radiol. 2016;57:1438-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharma P, Yadav S, Needham CM, Feuerstadt P. Sclerosing mesenteritis: a systematic review of 192 cases. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10:103-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Endo K, Moroi R, Sugimura M, Fujishima F, Naitoh T, Tanaka N, Shiga H, Kakuta Y, Takahashi S, Kinouchi Y, Shimosegawa T. Refractory sclerosing mesenteritis involving the small intestinal mesentery: a case report and literature review. Intern Med. 2014;53:1419-1427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA, Smyrk TC. Sclerosing mesenteritis: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in ninety-two patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:589-96; quiz 523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nyberg L, Björk J, Björkdahl P, Ekberg O, Sjöberg K, Vigren L. Sclerosing mesenteritis and mesenteric panniculitis - clinical experience and radiological features. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Coulier B. Mesenteric panniculitis. Part 1: MDCT--pictorial review. JBR-BTR. 2011;94:229-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Emory TS, Monihan JM, Carr NJ, Sobin LH. Sclerosing mesenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis and mesenteric lipodystrophy: a single entity? Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:392-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Allen PB, De Cruz P, Efthymiou M, Fox A, Taylor AC, Desmond PV. An Interesting Case of Recurrent Small Bowel Obstruction. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2009;3:408-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Corado SC, Almeida H, Baltazar JR. A severe case of sclerosing mesenteritis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haikal A, Thimmanagari K. Colon Perforation As Initial Presentation of Refractory and Complicated Sclerosing Mesenteritis. Cureus. 2021;13:e17142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Danford CJ, Lin SC, Wolf JL. Sclerosing Mesenteritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:867-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rothlein LR, Shaheen AW, Vavalle JP, Smith SV, Renner JB, Shaheen NJ, Tarrant TK. Sclerosing mesenteritis successfully treated with a TNF antagonist. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Reddington H, Ballinger Z, Abghari M, Modukuru V, Wallack M. Sclerosing Mesenteritis in a Patient Heterozygous for Factor V Leiden. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e926332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cervera R, Serrano R, Pons-Estel GJ, Ceberio-Hualde L, Shoenfeld Y, de Ramón E, Buonaiuto V, Jacobsen S, Zeher MM, Tarr T, Tincani A, Taglietti M, Theodossiades G, Nomikou E, Galeazzi M, Bellisai F, Meroni PL, Derksen RH, de Groot PG, Baleva M, Mosca M, Bombardieri S, Houssiau F, Gris JC, Quéré I, Hachulla E, Vasconcelos C, Fernández-Nebro A, Haro M, Amoura Z, Miyara M, Tektonidou M, Espinosa G, Bertolaccini ML, Khamashta MA; Euro-Phospholipid Project Group (European Forum on Antiphospholipid Antibodies). Morbidity and mortality in the antiphospholipid syndrome during a 10-year period: a multicentre prospective study of 1000 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1011-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 575] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 51.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zou X, Fan Z, Zhao L, Xu W, Zhang J, Jiang Z. Gastrointestinal symptoms as the first manifestation of antiphospholipid syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |