Published online May 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i14.3211

Peer-review started: December 27, 2022

First decision: February 2, 2023

Revised: February 18, 2023

Accepted: April 10, 2023

Article in press: April 10, 2023

Published online: May 16, 2023

Processing time: 139 Days and 12.5 Hours

The tinnitus susceptibility patterns in relation to different psychological and life stressors are unknown in different cultures.

To determine the comorbid psychosocial factors and behaviors associated with tinnitus and the predictors for the increase in its severity.

Participants were 230 adults (males = 70; females = 160; mean age = 38.6 ± 3.3). They underwent audiograms, speech discrimination and masking testing, and neuropsychiatric evaluation. Measures used for assessment included tinnitus handicap inventory, depression anxiety stress scale 21 (DASS-21), perceived stress scale (PSS), and insomnia severity index (ISI).

Patients had mean duration of tinnitus of 11.5 ± 2.5 mo. They had intact hearing perception at 250-8000 Hz and 95 (41.3%) had aggravation of tinnitus loudness by masking noise. Decompensated tinnitus was reported in 77% (n = 177). The majority had clinically significant insomnia (81.3%), somatic symptoms (75%) other than tinnitus and perceived moderate (46.1%) and high (44.3%) stress to tinnitus. The severe/extremely severe symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress were reported in 17.4%, 35.7% and 44.3%, respectively. Patients with decom-pensated type had significantly higher scores for ISI (P = 0.001) and DASS-21 (depression = 0.02, anxiety = 0.01, stress = 0.001) compared to those with com

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in our culture to evaluate the causal relationship between psychological factors and tinnitus onset, severity and persistence. Tinnitus could be the earliest and dominant somatic symptom induced by life stressors and psychological vulnerabilities. Therefore, multidisciplinary consultation (psychologists, psychiatrists, and neurologists) is important to acknowledge among the audiologists and otolaryngologists who primarily consult patients.

Core Tip: Tinnitus is a frequent subjective symptom in adults. About 15%-30% of patients with tinnitus have no clinically manifested hearing loss or no subclinical sensorineural hearing loss when evaluated using advanced auditory testing. There are several comorbid psychiatric conditions and disorders in sufferers of tinnitus, which may contribute to its persistence and increased severity. They include stress, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, increased forgetfulness, major depression and anxiety, and somatoform disorders. However, the relationship of these comorbidities with tinnitus onset is unclear. Also the psychosocial triggers for initiation, increased severity, and chronicity of tinnitus are understudied in many areas of the world.

- Citation: Hamed SA, Attiah FA, Fawzy M, Azzam M. Evaluation of chronic idiopathic tinnitus and its psychosocial triggers. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(14): 3211-3223

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i14/3211.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i14.3211

Tinnitus is the most common subjective auditory symptom with an estimated prevalence of 8%-20% (~14.4%) in adults and 35%-45% (~40%) in individuals aged ≥ 55-years-old. The prevalence of tinnitus is reduced after the 7th decade[1]. It has also been reported that tinnitus is a life-lasting disabling problem in 0.5%-2.5% of patients[1-3] and a handicapping problem in 1%-2%[4]. Tinnitus is defined as a sound heard in the ears or ears and head in absence of external auditory source. It is commonly described as ringing, whistling, buzzing, roaring and clicking and rarely as a combination of sounds or a non-defined sound. Some audiologists suggested that the majority of patients with tinnitus (~90%) might have a degree of hearing loss which varied from severe to very mild or subclinical[5]. However, others found tinnitus in 30% of patients without clinically manifest sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) and in 15% of patients without evidence of hearing impairment using advanced testing for detection of subclinical deficits[6]. They also suggested that persistence of tinnitus and aggravation of its severity overtime (decompensated tinnitus) highly indicate the presence of psychological or other physical (to less extent) comorbid conditions, because tinnitus due to lesions in the auditory system is often transient and disappears overtime due to brain filtering mechanisms regardless to the cause[6]. The common comorbid conditions in patients with chronic tinnitus include emotional stresses, mood swings and anxiety symptoms (28%-49%)[7-9], sleep problems (10%-80%)[10,11], poor attention and concentration (up to 70%)[9], and chronic physical diseases (21%-47%)[12]. Research studies have also reported that 45%-78% of patients with chronic tinnitus satisfied the criteria of at least one psychiatric disorder(s), for example, affective (~23.5%), anxiety (~35%) and somatoform (~25%) disorders[2,8,9,13-20].

Various medications and interventions are used in the treatment of tinnitus including vasodilators, vitamins, calcium channel blockers, antihistamines, anticonvulsants (e.g., valproate), gabapentin, antidepressants, anxiolytics, psychotherapy, biofeedback, and hypnosis. However, none have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Many clinicians agree that combined management strategies are more effective for the treatment of tinnitus[7,21-24].

Whether psychological/psychiatric factors are risk factors for tinnitus is understudied in different countries. Therefore, in this work, we aimed to determine the comorbid psychosocial factors and behaviors associated with tinnitus’s onset, severity, and chronicity; as well as the predictors for the increase in its severity.

This was a cross-sectional study, which included 230 adults (males = 70; females = 160) with chronic tinnitus. Patients were recruited from January 2020 to July 2022 from the outpatient Otolaryngology and Neuropsychiatry Clinics of Assiut University Hospital, Assiut Egypt. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Adults (20-55-years-old); (2) self-reported tinnitus as a main physical problem at presentation; (3) duration of tinnitus ≥ 6 mo; (4) normal results of previous routine audiometric testing which were done at different time points; and (5) normal imaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) of the brain and cervical spine or cord. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Pulsatile tinnitus; (2) manifested hearing loss; (3) local cause that explains tinnitus, for example, impacted wax, infections/inflammation of the ear, Meniere disease, otosclerosis, and presbycusis; (4) medical, neurological, or psychiatric disease, which can cause hearing impairment (e.g., diabetes, anemia, thyroid disease, stroke, small vessel disease, demyelinating lesions, migraine, epilepsy, tumor as acoustic neuromas, and psychosis); (5) head or cervical vertebra injuries; and (6) ototoxic drug use (e.g., aspirin, quinine, aminoglycosides, cancer chemotherapy as cisplatin).

Data collection included: (1) Demographics: age, sex, residence, marital state, educational level (classified as low if could not read or write, can read, primary or secondary school education; or high if high school, college, etc.) and socioeconomic state. The socioeconomic scale (SES) was used for determination of socioeconomic state. SES is a structured questionnaire used to gather data related to parents' education, family income per month, sanitation, and crowding index. SES total score is 30. SES was classified as high (score > 25 to ≥ 30), middle (score > 20 to ≥ 25), low (score ≥ 15 to ≤ 20), or very low (score < 15)[25]. Clinical characteristics were: completion of otological, medical, neurological, and psychiatric histories and examinations. Tinnitus inquiries included: Its duration, origin, description, laterality, intensity, pattern, and time of occurrence. The results of previous evaluations (audiograms, laboratory investigations and drug prescriptions for tinnitus) were also collected. The diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder was done according to the Structured Clinical Interviewing using Arabic version of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Revised (DSM-IV-TR)[26,27].

The diagnostic work-up questionnaires included: The Tinnitus handicap inventory (THI)[28] consists of 25 items, with 3 responses for each which are 1st response or ”yes” equals 4 points, 2nd response or ”sometimes” equals 2 points, or a 3rd response ”no” equals 0. Its total scores range from 0 to 100 points. Higher scores indicate greater perceived handicap. Tinnitus severity was classified as: (1) Grade 1 or slight (score 0-16) if tinnitus was heard only in quite environment, masked easily with environmental noise and did not interfere with sleep or daily activities; (2) Grade 2 or mild (score 18-36) if tinnitus was masked easily by environmental noise, neglected during life activities and occasionally interfered with sleep, but did not interfere with daily activities; (3) Grade 3 or moderate (score 38-56) if tinnitus could be noticed in noisy environment but the individual could still perform the daily activities; (4) Grade 4 or severe (score 58-76) if tinnitus was always heard, disturbed sleep and could interfere with daily activity; and (5) Grade 5 or catastrophic (score 78-100) if tinnitus was severe enough to interfere with any life activity. For comparative statistics, tinnitus was divided according to its severity into compensated tinnitus if THI grades were 1or 2 (i.e. slight or mild) and decompensated tinnitus if THI grades were 3, 4, or 5 (i.e. moderate, severe or catastrophic).

Insomnia severity index (ISI) is a 7-item questionnaire[29]. The total score categories are: (1) No clinically significant insomnia (score 0-7); (2) sub-threshold insomnia (score 8-14); (3) moderately severe clinically significant insomnia (score 15-21); and (4) severe clinically significant insomnia (score 22-28).

Depression anxiety stress scale 21 (DASS-21)[30] is 21 items, which produces results for the recent (past week) symptoms. The DASS-21 scores for depression or anxiety or stress symptoms were determined separately. They were classified as normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme.

Perceived stress scale (PSS)[31,32] is a 14-item scale. Each item is rated by a 5-point Likert scale which range from 0: “never” to 4: “very often.” The total score of each individual was calculated by reversing the scores on these positive seven items (B4, B5, B6, B7, B9, B10, and B13), followed by adding the responses to the rest of the 14 items. PSS does not reflect a specific diagnosis or course for treatment; therefore, it has no cut-off value. PSS scores range from 0 to 56. Accordingly, subjects were classified according to the perceived stress level to tinnitus (as stressor) into: (1) Perceived low stress if scores were 0 to 13; (2) perceived moderate stress if scores were 14 to 26; and (3) perceived high stress if scores were 27 to 40.

A designed questionnaire for determination of life stressors. The term "life stressor" is defined as extraordinary and undesirable major life events or conditions of clear onset and offset. We designed a simple questionnaire based on the common major stressors in our population which included financial, marital, siblings, changes in personal work or home activities, troubles with law, and problems with close relatives or a friend.

Basic audiologic evaluation: It included pure tone audiometry, which was assessed at frequency ranges from 250 Hz to 8000 Hz (interacoustic model AC 40), tympanometry (interacoustic model AZ 26), measurement of acoustic reflex threshold (interacoustic model AZ 26), and speech discrimination test. Speech discrimination score (SDS) is defined as the hearing level to understand and repeat at least 25 Arabic phonetically balanced monosyllabic words. SDS of 90% to 100% was considered normal. For patients who noticed tinnitus at quite occasions (e.g., at bedtime), a masking test was also done using a white noise machine.

Data were analyzed with SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY, United States). The distributional properties of variables and appropriateness of the analyses of covariance were confirmed. Comparative statistics were done using the two-sided Student’s t-test, χ2 test, and one way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc correction. Inferential statistics were performed using Spearman's correlation coefficient between: (1) Scores of THI and age, duration of tinnitus, and scorings of DASS-21 (depression, anxiety, and stress), PSS and ISI; (2) scores of DASS-21 and PSS and ISI; and (3) scores of PSS and ISI. Multivariate analysis was done to detect the independent variables associated with THI. First, univariate analysis was done between scores of THI and duration of tinnitus and scores of ISI, DASS-21, and PSS. Variables that showed significant values in the univariate model were entered into the multivariate model. Results are expressed as the odds ratio (OR) and 95%CI. Significance was calculated at P < 0.05.

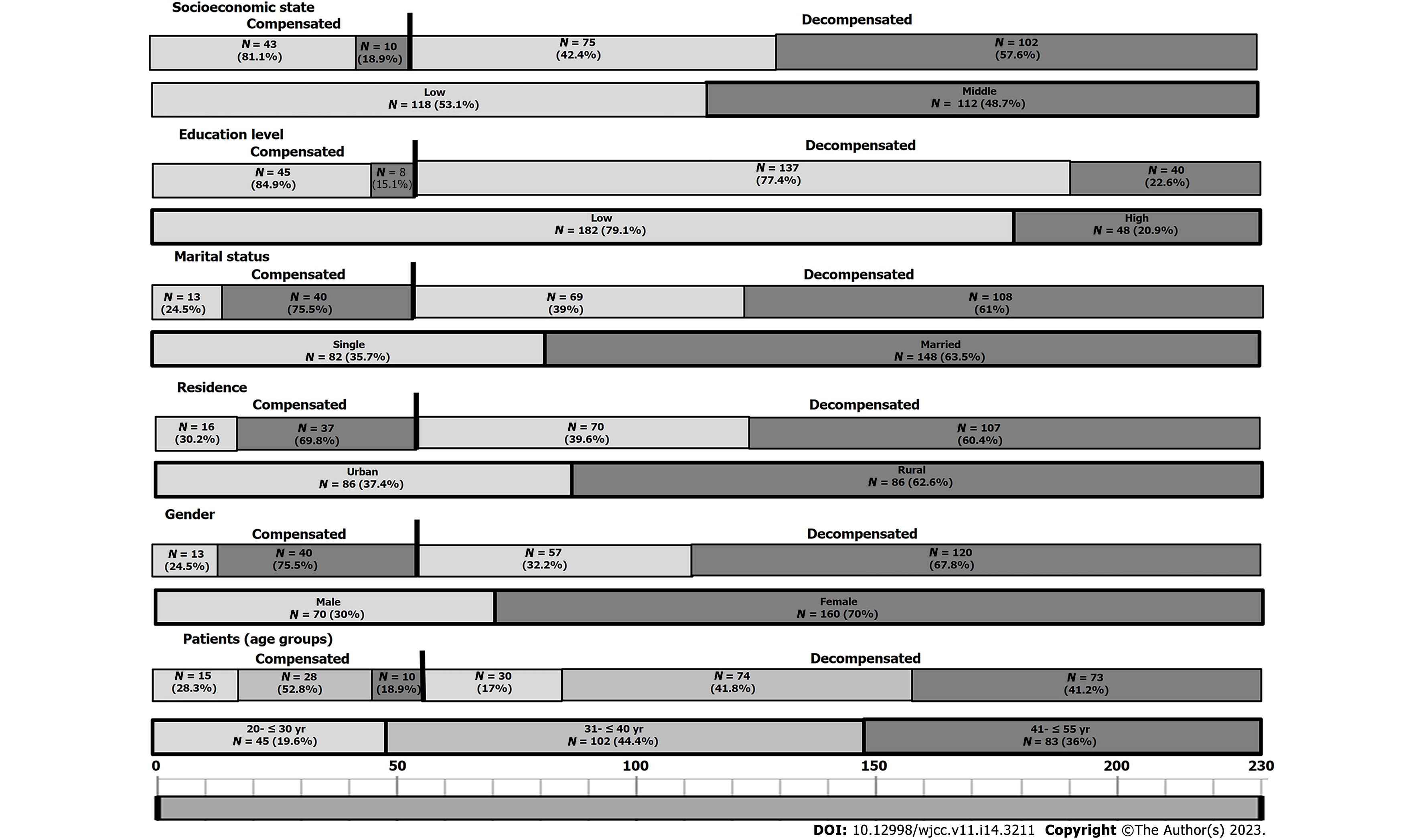

Participants were 230 adults with chronic tinnitus, ranging in age from 25 years to 50 years (mean = 38.6 ± 3.3). The mean duration of tinnitus at the time of the study was 11.5 ± 2.5 mo (range: 6 to 24 mo). The majority were in their 3rd decade and 4th decade (n = 147, 64%), females (69.6%), rural residents (62.6%), married (63.5%), of low education (79.1%), and low/middle socioeconomic states (53%). They had intact hearing perception at 250-8000 Hz, SDS, and type A tympanometry. One hundred and forty patients(60.87%) had tinnitus at quite (or bedtime) and 95 of them (or 67.86%) had aggravation of tinnitus loudness by masking noise. Decompensated tinnitus was reported in 77% (n = 177; G3 = 52 or 22.6%, G4 = 62 or 27% and G5 = 63 or 27.4%) and compensated tinnitus was reported in 23% (n = 53; G1 = 15 or 6.5%, and G2 = 38 or 16.5%). Figure 1 shows the demographics of the studied patients and the differences in demographics between patients with compensated vs decompensated tinnitus. There were no significant differences between the two groups of patients in relation to different variables. Table 1 shows the characteristics of tinnitus. It showed that the most frequently encountered sounds were whistling (33.04%) and different sounds’ descriptions in different occasions (27%), while clicking (7.4%) and sound echo (4%) were the least described types. Bilateral tinnitus of equal intensity in both ears was more frequent than unilateral. Tinnitus was either continuous or periodic. Thirty percent of patients found that ear plugging resulted in reduced tolerance to tinnitus loudness. There were no significant differences in the tinnitus characteristics between patients with compensated and decompensated types, except that the latter had significantly longer duration of tinnitus at presentation (P = 0.03).

| Characteristics | Patients, n = 230 | Compensated tinnitus, n = 53 | Decompensated tinnitus, n = 177 | P value |

| Duration of tinnitus in mo | 6-24 (11.5 ± 2.5) | 10.6 ± 2.2 | 14.3 ± 2.3 | 0.03 |

| 55 (23.9) | 8 (15.1) | 47 (26.6) | ||

| 127 (55.2) | 7 (13.2) | 120 (67.8) | ||

| 48 (20.9) | 38 (71.7) | 10 (5.7) | ||

| Origin of sound | ||||

| 147 (63.9) | 38 (71.7) | 109 (61.6) | ||

| 83 (36.1) | 15 (28.3) | 68 (38.4) | ||

| Description | ||||

| 32 (14) | 14 (26.4) | 18 (10.2) | ||

| 76 (33) | 14 (26.4) | 62 (35) | ||

| 34 (14.8) | 13 (24.5) | 21 (11.9) | ||

| 17 (7.4) | 0 | 17 (9.6) | ||

| 9 (4) | 0 | 9 (5.1) | ||

| 62 (27) | 12 (22.6) | 50 (28.3) | ||

| Laterality | ||||

| 63 (27.4) | 3 (5.7) | 60 (33.9) | ||

| 132 (57.4) | 38 (71.7) | 94 (53.1) | ||

| 98 (43.6) | 30 (56.6) | 68 (38.4) | ||

| 34 (14.8) | 8 (15.1) | 26 (14.7) | ||

| 35 (15.2) | 12 (22.6) | 23 (13) | ||

| Pattern | ||||

| 120 (52.2) | 28 (42.8) | 92 (52) | ||

| 110 (47.8) | 25 (47.2) | 85 (48) | ||

| Time of occurrence | ||||

| In silence, e.g., at bed time | 140 (60.8) | 25 (47.2) | 115 (65) | |

| In presence of noise or silence | 90 (39.1) | 28 (42.8) | 62 (35) |

Table 2 shows the results of the diagnostic work-up questionnaires and psychiatric interviewing of patients. It showed that the majority had clinically significant insomnia (n = 187, 81.3%). The severe and extremely severe symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress were reported in 17.4% (n = 40), 35.7% (n = 82), and 48.7% (n = 112) of patients, respectively. Also, the majority of patients had perceived moderate (n = 106 or 46.1%) and high (n = 102 or 44.3%) stress to tinnitus. There were no sex differences in scores of ISI, DASS-21, and PSS. Patients with decompensated type had significantly higher scores for ISI (P = 0.001) and DASS-21 (depression = 0.02, anxiety = 0.01, stress = 0.001) compared to those with compensated tinnitus.

| Characteristics | Patients, n = 230 | Compensated, n = 53 | Decompensated, n = 177 | P value |

| Type of insomnia | ||||

| 43 (18.7) | 10 (18.9) | 33 (18.6) | ||

| 129 (52.2) | 25 (47.2) | 104 (58.8) | ||

| 58 (23.2) | 18 (34) | 40 (22.6) | ||

| 20.6 ± 5.3 | 14.3 ± 2.4 | 28.6 ± 2.3 | 0.001 | |

| DASS-21 | ||||

| 45 (19.6) | 14 (26.4) | 31 (17.5) | ||

| 85 (37) | 23 (43.4) | 62 (35) | ||

| 60 (26.1) | 12 (22.6) | 48 (27.1) | ||

| 28 (12.2) | 4 (7.6) | 24 (13.6) | ||

| 12 (5.2) | 0 | 12 (6.8) | ||

| 15.88 ± 3.26 | 14.08 ± 2.46 | 22.68 ± 2.26 | 0.02 | |

| 12 (5.2) | 12 (22.6) | 0 | ||

| 16 (7) | 14 (26.4) | 2 (1.1) | ||

| 120 (52.2) | 8 (15.1) | 112 (63.3) | ||

| 58 (25.2) | 19 (35.9) | 39 (22) | ||

| 24 (10.4) | 0 | 24 (13.6) | ||

| 28.65 ± 2.80 | 22.42 ± 2.33 | 30.55 ± 2.08 | 0.01 | |

| 10 (4.4) | 2 (3.8) | 8 (4.5) | ||

| 12 (5.2) | 3 (5.7) | 9 (5.1) | ||

| 106 (46.1) | 40 (75.5) | 66 (37.3) | ||

| 60 (26.1) | 8 (26.1) | 52 (29.4) | ||

| 42 (18.3) | 0 | 42 (23.7) | ||

| 38.32 ± 3.86 | 23.82 ± 2.40 | 42.88 ± 2.23 | 0.001 | |

| PSS | ||||

| 12 (5.2) | 3 (5.7) | 9 (5.1) | ||

| 106 (46.1) | 30 (56.6) | 76 (42.9) | ||

| 112 (48.7) | 20 (37.7) | 92 (51.98) | ||

| Comorbid physical and psychiatric conditions | ||||

| 40 (17.4) | 8 (26.1) | 32 (18.1) | ||

| 82 (35.7) | 18 (34) | 64 (35) | ||

| 45 (19.6) | 3 (5.7) | 42 (23.7) | ||

| 88 (38.3) | 23 (43.4) | 65 (36.7) | ||

| 110 (47.9) | 32 (60.4) | 78 (44.1) | ||

| 95 (41.3) | 20 (37.7) | 75 (42.4) | ||

| 73 (31.7) | 26 (49.1) | 47 (26.6) | ||

| Family history of psychiatric disorders | 18 (7.8) | 6 (11.3) | 12 (6.8) |

There were high frequencies of patients with somatic symptoms (75%) other than tinnitus. They included non-specific headache (47.9%), gastrointestinal symptoms (41.3%) (e.g., vomiting, bloating, diarrhea, abdominal gaseous distention, and colic without definite etiology or similar concurrent conditions in close household contacts), poor concentration (38.3%), and erectile dysfunction (31.7%). Psychiatric interviewing showed that 35.7% had non-specific anxiety disorder, 17.4% had major depression, and 19.6% fulfilled the criteria of somatization disorder. Higher frequency of somatization disorder (23.7% vs 5.7%) and sexual dysfunction (49% vs 26.6%) were reported in patients with decompensated compared to those with compensated tinnitus. Family history of psychiatric disorders was reported in only 9.57% of patients.

The most frequently reported life stressors were financial (77.4%), marital (73%), and sibling (69.6%) issues. Few (8.83%) denied the presence of life stressors (Table 3). We observed that there were no significant differences in the frequencies of life stressor for patients with decompensated compared to those with compensated tinnitus.

| No. | Most stressful life events or changes | Total, n = 230 | Compensated, n = 53 | Decompensated, n = 177 |

| 1 | Financial issues: Change in financial state; Accumulation of loans; Stopped work or fired at work (either subject or a spouse) | 178 (77.39) | 27 (50.94) | 151 (85.31) |

| 2 | Marital issues: Trouble with spouse; Marital separation; Divorce; Death of spouse | 168 (73.04) | 3 (5.66) | 165 (93.22) |

| 3 | Siblings' issues: Change in health; Death; Left home; Poor achievement at school or college or work; Stopped work | 160 (69.57) | 20 (37.74) | 140 (79.10) |

| 4 | Change in personal issues: Lower home daily activities; Lower work activities; Poor social activities; Change in personal habits; Change in religion habits | 120 (52.17) | 0 | 120 (67.80) |

| 5 | Work or home activities' issues: Work readjustment; Change in work hours or conditions; Change to a different line of work; Change a different responsibility at work; Change in sleeping habits or frequent daytime shifts | 63 (27.39) | 0 | 63 (35.59) |

| 6 | Trouble with law issues | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | A close relatives' or a friends' issues: Change in health; Death | 50 (21.74) | 3 (5.66) | 47 (26.55) |

| 8 | None | 18 (8.83) | 0 | 18 (10.17) |

Significance correlations were found between the duration of tinnitus and its severity and perceived stress towards it and severities of depression, anxiety and stress symptoms, and insomnia; between perceived stress towards tinnitus and severities of depression, anxiety and stress symptoms, and insomnia; and between severities of insomnia and depression, anxiety and stress symptoms (Table 4). Univariate analysis showed that there were significant correlations between THI scores and duration of tinnitus (OR = 0.913, 95%CI: 0.758-1.262; P = 0.02) and scores of ISI (OR = 0.853, 95%CI: 0.650-1.128; P = 0.001), DASS21 (depression: OR = 0.430, 95%CI: 0.320-0.656; P = 0.01; anxiety: OR = 1.156, 95%CI: 0.886-1.902; P = 0.001; stress: OR = 0.932, 95%CI: 0.843-1.230; P = 0.001) and PSS (OR = 0.923, 95%CI: 0.643-1.258; P = 0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that the only independent predictors for tinnitus severity (THI score) were the duration of tinnitus (OR = 0.832, 95%CI: 0.640-1.158; P = 0.001) and PSS score (OR = 0.835, 95%CI: 0.540-1.125; P = 0.001).

| Parameter | Duration | THI | ISI | PSS |

| Duration | ||||

| 0.358 (0.01) | ||||

| ISI | 0.520 (0.001) | 0.653 (0.001) | ||

| DASS-21 | ||||

| 0.362 (0.04) | 0.325 (0.033) | 0.350 (0.02) | 0.358 (0.01) | |

| 0.540 (0.001) | 0.386 (0.02) | 0.520 (0.001) | 0.626 (0.001) | |

| 0.565 (0.001) | 0.543 (0.001) | 0.624 (0.001) | 0.580 (0.001) | |

| PSS | 0.338 (0.01) | 0.545 (0.001) | 0.545 (0.001) | |

The topic of chronic idiopathic tinnitus and its relationship to psychological factors is understudied in different countries. The core outcome domain of this study was identification of psychosocial associates with tinnitus’s onset, severity, and persistence. Generally speaking, previous studies have included the following information about tinnitus: (1) Lesions in the auditory sensory pathway and its brain circuits often produce high-pitched tinnitus (i.e. hearing loss is dominant in high-frequency tone sound stimuli with ranges more than 4000 Hz. These ranges are not routinely tested in audiology clinics[5]. Tinnitus caused by auditory pathway lesions is often transient and disappears spontaneously within short time regardless to its etiology. This is due to the activation of thalamic filtering processes by the superior brain centers (i.e. switch-off the aberrant signals expressed as noisy ear sounds). This process is termed habituation or adaptation[6]; (2) Clinicians observed that it is impossible at onset to predict the course of tinnitus or whether an individual will develop compensated or decompensated tinnitus overtime. However, audiologist and otologists usually advice the majority (~80%) of individuals with tinnitus against frequent consultations as long as there is no hearing deficits and intact comprehensive of speech, and to become accustomed to tinnitus[16,20] as there is/are no standard symptomatic treatment(s) for tinnitus. The clinicians also observed that there is no direct relation between tinnitus loudness and the severity of SNHL. There are individuals with very severe hearing loss but never experienced tinnitus[6]. In contrast, some clinicians reported an association between the estimates of hearing loss and tinnitus loudness. However, such studies were criticized as their authors did not exclude (during analyses) the co-variables which could associate with tinnitus severity (as emotional stress or psychosocial factors)[5,15]; (3) Most studies are focused on tinnitus as a somatic stressor, i.e. the cause of adverse mental health. They also suggested that the suffers of tinnitus seem to be more vulnerable to significant stress[16]. However, few indicated that tinnitus may begin in times of severe stress or after a period of significant stress[20]; and (4) In many countries, the management of chronic tinnitus may include interdisciplinary approach (i.e. neurologists, audiologists, psychologists and psychiatrists)[1-3].

In our sample, the women to men ratio, was 2.3:1. The sex difference in prevalence of chronic tinnitus is a subject of debate. Some studies have reported higher frequencies in females. Others found the reverse[12,18]. In this study, the higher frequency of participants from females could be explained by the following: (1) Females may be vulnerable to develop chronic tinnitus than male; (2) being housewives, females had free times for consultations than males; (3) females are commonly express their somatic symptoms, feelings and stress more easily and frequently compared to males; and (4) females with or without tinnitus had higher psychological risks throughout their lives and were more likely to exhibit emotional disturbances (e.g., mood swings, anxiety and stress), while males tended to experience depression and social isolation[9].

In this study, psychiatric interviewing revealed that participants had higher frequencies and severities of insomnia, anxiety and stress symptoms. Many patients (75%, n = 172) had repeated somatic symptoms in addition to tinnitus, which are distressing or result in significant disruption of daily life. They included insomnia, headache, gastrointestinal tract (GIT) symptoms (e.g., vomiting, bloating, diarrhea) without explanatory cause, erectile dysfunction, and memory deficits. These manifestations were marked in patients with decompensated tinnitus.

Considering the age of participants at presentation, ~20% satisfied the DSM-IV criteria of somatization disorder, a class of somatoform disorders[26,27]. The same criteria were applied for the classification in DSM-IV as “somatic symptom disorder,” a class of somatic symptom and related disorder[33]. These criteria were previously termed “psychosomatic or psycho-physiologic disorders.” Non-specific anxiety disorder was reported in 35.65%. Major depressive disorder was reported in 17.39%.

Exploring the psychosocial stressors, the majority (77%) had drastic financial, marital, or sibling stressful life events. Accordingly, previous studies have reported that 45%-78% of patients with chronic idiopathic tinnitus satisfied the criteria of one or more psychiatric disorders[2,7-14,16-18]. Some studies have considered the role of stress-reactivity in tinnitus onset[6,19,20]. Belli et al[17] showed that 27% of patients with tinnitus had at least one psychiatric diagnosis (as anxiety disorders in 28%, somatoform and mood disorders in 15%, and personality disorders in 3%) vs 5.6% for control subjects. The authors suggested that, the psychological stressor greatly impacts the body physiological function with improper stimulation of the autonomic nervous system, excess adrenaline secretion and severe stress and anxiety and somatization. Fagelson[34] did a chart review for enrolled patients to tinnitus service in the Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The authors reported that 34% of patients with tinnitus also fulfilled the criteria for the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They also reported that the following tinnitus inquiries were more frequent in patients with tinnitus and PTSD compared to those with tinnitus only, they include sudden onset of tinnitus, increased tinnitus severity, poor tolerance to sounds and exaggeration of tinnitus with sounds. The authors suggested that there might be several shared neural mechanisms between tinnitus and PTSD and affect auditory behaviors (i.e. mutual reinforcement of symptoms of both tinnitus and PTSD). Furthermore, several studies reported that the chronic and severe tinnitus, which followed traumatic brain injury, whether the involved individuals were from military or civil personnel, is due to the emotional trauma or the higher distress level which was experienced during the trauma event and not directly associated with the specific head or neck injury[35,36].

We observed the following associates and characteristics of tinnitus in the majority of patients, which highly suggest a contribution of non-sensorineural auditory problem: (1) There was no deterioration of hearing over time with repeated audiometric tests despite increase in tinnitus severity in the majority (77%); (2) In the same individual in different occasions, tinnitus originated from inside the head or the ear or both (36.09%), alternate in origin from either left or right (15.22%) and had different descriptions (e.g. ringing at sometimes and another description at another time) (27%); (3) The bilateral presentation and equal intensity in both ears since onset (43.61%); (4) The descriptions of tinnitus as whistling (33.04%), roaring (14.78%), clicking (7.4%) or sound echo (4%), which are non-familiar descriptions for tinnitus associated with SNHL; (5) The non-continuous or periodic pattern (47.83%); (6) Tinnitus was aggravated or became intolerable with ear plugging or masking noise (41.30%); and (7) Tinnitus severity and its perceived stress were associated with the severity of anxiety, stress and depression symptoms and insomnia[15,16,20].

Research studies have shown that insomnia reduces tolerance and increases the perceived annoyance to tinnitus[10,17,37]. Authors have linked the conscious perception of tinnitus and its loudness with time and insomnia to the hyperarousal induced by hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system[38]. We also found that the only independent associates to severe tinnitus were its chronicity and higher perceived stress towards it. We suggested that psychological factors influence the conscious perception of tinnitus, result in worsening of tinnitus (e.g., became continuous, increase in its loudness, and prolonged its duration) and also generate other functional somatic conditions such as headache, poor concentration, and GIT manifestations, erectile dysfunction. Research studies have found an independent association between neuroticism, obsession and anxiety traits and tinnitus severity[15,16]. It has been suggested that focusing attention on tinnitus increases fear, tension and anxiety, and emotional reinforcements followed by emotional exhaustion, neuronal hyperexcitability, establishment of a neuronal plasticity in the limbic system, particularly the amygdala and a vicious circle, resulting in chronic and severe continuous perception of tinnitus[13,14,17,39].

The results of this study support the fact that the psychological factors play an important role in the processes of perception, interpretation, treatment, and complications of tinnitus[40]. Therefore, combined multidisciplinary management of patients with tinnitus is required. Neuropsychiatric evaluation has to include counseling, education, and reassurance, and reduction of depression, anxiety and stress, and improving sleep pattern by psychotropic medication, psychotherapy or other interventions[21-24]. Psychotropic drugs improve tinnitus by improving the depression anxiety, stress and sleep disturbance. The previously used medication which have shown efficacy included tricyclic antidepressants (as amitriptyline, nortriptyline and trimipramine) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (as sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine)[21]. Folmer et al[21] in their retrospective study on 30 patients with depression and started treatment with SSRIs and psychotherapy for 20.6 mo after tinnitus onset, the authors demonstrated a significant improvement of tinnitus as evidenced by reduction of tinnitus severity index scores. The authors concluded that, SSRIs elevated affectivity which accompanied tinnitus and therefore reduced the intensity and frequency of tinnitus. However, some studies found that although SSRIs improve symptoms of depression and anxiety but may worsen tinnitus[22,41]. In tinnitus mouse models, Tang et al[42] analyzed the brain tissue which focused on the response of neurons in the dorsal cochlear nucleus to serotonin. The dorsal nucleus is the portion of the cochlear nucleus with inhibitory characteristics and involved in sensory processing. It is the portion of the cochlear nucleus which is affected by tinnitus. The authors observed hyperactivity and hypersensitivity of the mice to sounds when the fusiform cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus were exposed to serotonin, indicating that serotonin raises neuronal activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. They also suggested that serotonin suppresses signaling through the auditory pathway and enhances transmission through a multisensory pathway. Previous studies have also suggested that the main aim for the use of psychotropic medications is to treat the co-morbid anxiety/depression in patients with tinnitus and not as a main symptomatic treatment of tinnitus. Because not all psychotropic medications can worsen tinnitus, it is plausible to suggest that it is better to switch to another psychotropic drug to improve depression and anxiety symptoms without deterioration of tinnitus.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in our culture to evaluate the causal relationship between psychological factors and tinnitus onset, severity and persistence. However, this study has limitations which include a female predominance (i.e. sex bias), however, we do not consider this a major weakness as statistical analyses were also done after classification of patients from both sex into those with compensated vs decompensated tinnitus.

Tinnitus was an infrequent earliest and dominant somatic symptom induced by severe life stressors and psychological vulnerabilities. In many patients, the characters of tinnitus were distinguished from that of solely auditory system lesions. Psychiatric interviewing revealed the diagnosis of anxiety disorder in 35.7%, somatization disorder in 19.6% and major depression in 17.4% of patients. Tinnitus severity was independently associated with the longer duration of tinnitus and the individual's perceived stress towards tinnitus. Therefore, multidisciplinary consultation (psychologists, psychiatrists and neu-rologists) is important to acknowledge.

Tinnitus is the most common auditory symptom with an estimated prevalence of 8%-40% and life-long disabling problem in ~2.5%. Tinnitus is an aberrant sound heard in the ears or in both ears and head. It is believed to be a symptom of hearing impairment. However, many audiologists observed that approximately 15%-30% of subjects with tinnitus had neither manifest nor subclinical hearing impairment. Research studies have indicated that psychosocial factors as stress, anxiety, depression and insomnia are strong risks for the chronic and severe tinnitus. They also reported comorbid psychiatric disorders as anxiety, somatization and major depressive disorders in 23%-35% of patients with tinnitus. Others reported improvement of tinnitus after the use of antidepressant or anxiolytic medications. Many audiologist and otolaryngologist believe that tinnitus requires multidisciplinary evaluation and management. As chronic idiopathic tinnitus and evaluation of its psychosocial triggers is an understudied topic in many parts of the world, therefore, it has to be addressed in different populations.

The research hotspots include determination of: (1) Characteristics of chronic tinnitus in group of patients with no obvious hearing loss as a cause; (2) comorbid psychosocial stressors and psychiatric conditions and disorders which are associated with tinnitus initiation, aggravation and chronicity; and (3) predictors that are independently associated with increase in the severity of tinnitus.

This study systematically assessed patients with chronic idiopathic tinnitus and the psychosocial factors associated with its onset, increased severity and chronicity.

Tinnitus handicap inventory, depression anxiety stress scale 21, perceived stress scale, insomnia severity index, and a designed questionnaire for determination of life stressors.

This study included 230 adult patients from both sex. They had chronic tinnitus with a mean duration of approximately 11 mo. Their previous ear, nose and throat and audiology evaluations including pure tone audiometry at frequencies ranged from 250 to 8000 Hz did not reveal obvious cause for tinnitus. Decompensated tinnitus was reported in 77%. The characters of tinnitus in many patients are distinguished from that of tinnitus due to pure auditory pathway lesions, which included being originated from ears and/or head, bilateral or alternate ear side, described as whistling, roaring, clicking, or combined sound, aggravated by ear plugging, stress, anxiety and insomnia and absence of hearing deterioration overtime. Psychiatric evaluation revealed frequent comorbid conditions and disorders including stress, anxiety, somatic problems, depression, enhanced perceived stress towards tinnitus and anxiety, somatization and major depressive disorders. We also reported that the variables which were highly significant and independently associated with tinnitus were its duration and increased stress perception towards tinnitus.

Tinnitus was a common and predominant somatic symptom in response to severe life stressors and psychological susceptibility. The tinnitus variables showed distinct characteristics which differentiate it from tinnitus caused by pure auditory system lesions. Psychiatric interviewing revealed that the majority of patients had symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance of variable severities. Anxiety and somatization disorders were reported in 35.7% and 19.6% of patients, respectively. Major depressive disorder was reported in 17.4%. The interindividual variability to stress perception and anxiety were strong triggers for tinnitus, its severity and chronicity.

In our locality, the importance of the psychosocial factors for the initiation, aggravation and chronicity of tinnitus are understudied. Multidisciplinary consultation (psychologists, psychiatrists and neurologists) is important to acknowledge among the audiologists and otolaryngologists who primarily consult patients. Also future longitudinal studies are required to determine the tinnitus outcomes before and after treatment with psychotropic medications.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sahin Y, Turkey; Sfera A, United States S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med. 2010;123:711-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 629] [Article Influence: 41.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Krog NH, Engdahl B, Tambs K. The association between tinnitus and mental health in a general population sample: results from the HUNT Study. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:289-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Martinez-Devesa P, Perera R, Theodoulou M, Waddell A. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD005233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Heller AJ. Classification and epidemiology of tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36:239-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schlee W, Kleinjung T, Hiller W, Goebel G, Kolassa IT, Langguth B. Does tinnitus distress depend on age of onset? PLoS One. 2011;6:e27379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Georgiewa P, Klapp BF, Fischer F, Reisshauer A, Juckel G, Frommer J, Mazurek B. An integrative model of developing tinnitus based on recent neurobiological findings. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66:592-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Robinson SK, McQuaid JR, Viirre ES, Betzig LL, Miller DL, Bailey KA, Harris JP, Perry W. Relationship of tinnitus questionnaires to depressive symptoms, quality of well-being, and internal focus. Int Tinnitus J. 2003;9:97-103. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Stobik C, Weber RK, Münte TF, Walter M, Frommer J. Evidence of psychosomatic influences in compensated and decompensated tinnitus. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:370-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zöger S, Svedlund J, Holgers KM. Relationship between tinnitus severity and psychiatric disorders. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:282-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Erlandsson SI, Hallberg LR, Axelsson A. Psychological and audiological correlates of perceived tinnitus severity. Audiology. 1992;31:168-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Folmer RL, Griest SE. Tinnitus and insomnia. Am J Otolaryngol. 2000;21:287-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zirke N, Seydel C, Arsoy D, Klapp BF, Haupt H, Szczepek AJ, Olze H, Goebel G, Mazurek B. Analysis of mental disorders in tinnitus patients performed with Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:2095-2104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sullivan MD, Katon W, Dobie R, Sakai C, Russo J, Harrop-Griffiths J. Disabling tinnitus. Association with affective disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10:285-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Halford JB, Anderson SD. Anxiety and depression in tinnitus sufferers. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35:383-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hiller W, Janca A, Burke KC. Association between tinnitus and somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res. 1997;43:613-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Møller AR. Misophonia, phonophobia, and "exploding head" syndrome. In Møller AR, Langguth B., De Ridder D, Kleinjung T. Textbook of tinnitus. New York: Springer, 2011: 25-27. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Belli H, Belli S, Oktay MF, Ural C. Psychopathological dimensions of tinnitus and psychopharmacologic approaches in its treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:282-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aytac I, Baysal E, Gulsen S, Tumuklu K, Durucu C, Mumbuc LS, Kanlikama M. Masking Treatment and its Effect on Tinnitus Parameters. Int Tinnitus J. 2017;21:83-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mazurek B, Olze H, Haupt H, Szczepek AJ. The more the worse: the grade of noise-induced hearing loss associates with the severity of tinnitus. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:3071-3079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abbas J, Aqeel, M, Jaffar A, Nurunnabi M, Bano S. Tinnitus perception mediates the relationship between physiological and psychological problems among patients. J Exp Psychopathol. 2019;1-15. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Folmer RL, Shi YB. SSRI use by tinnitus patients: interactions between depression and tinnitus severity. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83:107-108, 110, 112 passim. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Zöger S, Svedlund J, Holgers KM. The effects of sertraline on severe tinnitus suffering--a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Aazh H, El Refaie A, Humphriss R. Gabapentin for tinnitus: a systematic review. Am J Audiol. 2011;20:151-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Savage J, Waddell A. Tinnitus. BMJ Clin Evid. 2014;2014. [PubMed] |

| 25. | El-Gilany A, El-Wehady A, El-Wasify M. Updating and validation of the socioeconomic status scale for health research in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18: 962-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P) biometrics research. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, 2002. |

| 27. | Khalil AH, Abou El Ella EI, Hamed MAM, Lotfy MM. Systematic review of some epidemiological studies on psychiatric disorders in Egypt. M.Sc. Thesis, Ain Shams University. 2009. |

| 28. | Barake R, Rizk SA, Ziade G, Zaytoun G, Bassim M. Adaptation of the Arabic Version of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:508-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Suleiman KH, Yates BC. Translating the insomnia severity index into Arabic. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Moussa MT, Lovibond P, Laube R, Megahead HA. Psychometric Properties of an Arabic Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS). Res Soc Work Pract. 2017;27:375-386. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Cohen JN, Taylor Dryman M, Morrison AS, Gilbert KE, Heimberg RG, Gruber J. Positive and Negative Affect as Links Between Social Anxiety and Depression: Predicting Concurrent and Prospective Mood Symptoms in Unipolar and Bipolar Mood Disorders. Behav Ther. 2017;48:820-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Almadi T, Cathers I, Hamdan Mansour AM, Chow CM. An Arabic version of the perceived stress scale: translation and validation study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:84-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

| 34. | Fagelson MA. The association between tinnitus and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Audiol. 2007;16:107-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | American Tinnitus Association. ATA’s top 10 most frequently asked questions. [cited 2 July 2012]. Available at: http://www.ata.org/for-patients/faqs. |

| 36. | Kreuzer PM, Landgrebe M, Schecklmann M, Staudinger S, Langguth B; TRI Database Study Group. Trauma-associated tinnitus: audiological, demographic and clinical characteristics. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Malouff JM, Schutte NS, Zucker LA. Tinnitus-related distress: A review of recent findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Rauschecker JP, Leaver AM, Mühlau M. Tuning out the noise: limbic-auditory interactions in tinnitus. Neuron. 2010;66:819-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 603] [Cited by in RCA: 538] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Salvi R, Sun W, Ding D, Chen GD, Lobarinas E, Wang J, Radziwon K, Auerbach BD. Inner Hair Cell Loss Disrupts Hearing and Cochlear Function Leading to Sensory Deprivation and Enhanced Central Auditory Gain. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hallam RS. Psychological Approaches to the Evaluation and Management of Tinnitus Distress. In: Hazzel JWP. Tinnitus. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone, 1987: 156-175. |

| 41. | Miller CW. Development of Tinnitus at a Low Dose of Sertraline: Clinical Course and Proposed Mechanisms. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:1790692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Tang ZQ, Trussell LO. Serotonergic Modulation of Sensory Representation in a Central Multisensory Circuit Is Pathway Specific. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1844-1854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |