Published online May 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i13.2966

Peer-review started: December 21, 2022

First decision: February 8, 2023

Revised: March 7, 2023

Accepted: April 4, 2023

Article in press: April 4, 2023

Published online: May 6, 2023

Processing time: 124 Days and 14.5 Hours

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve quality of life in patients and its families against life threatening diseases, through suffering’s prevention and relief. It is the duty of the dental surgeon to possess the knowledge needed to treat a patient with little life span, in order to establish an adequate treatment plan for each situation.

To synthesize the published evidence on oral conditions, impact, management and challenges in managing oral conditions among palliative patients.

Articles were selected from PubMed and Scopus electronic platforms, using a research strategy with diverse descriptors related to “palliative care”, “cancer” and “oral health”. The article’s selection was done in two phases. The first one was performed by the main researcher through the reading of the abstracts. In the second phase two researchers selected eligible articles after reading in full those previous selected. Data was tabulated and analyzed, obtaining information about what is found in literature related to this subject and what is necessary to be approached in future researches about PC.

As results, the total of 15 articles were eligible, being one a qualitative analysis, 13 (92.8%) clinical trials and one observational study. Of the 15 articles, 8 (53.4%) involved questionnaires, while the rest involved: one systematic review about oral care in a hospital environment, 2 oral exams and oral sample collection, one investigation of terminal patient’s (TP) oral assessment records, 2 collection of oral samples and their respective analysis and one treatment of the observed oral complications.

It can be concluded that the oral manifestations in oncologic patients in terminal stage are, oral candidiasis, dry mouth, dysphagia, dysgeusia, oral mucositis and orofacial pain. Determining a protocol for the care of these and other complications of cancer – or cancer therapy – based on scientific evidence with the latest cutting-edge research results is of fundamental importance for the multidisciplinary team that works in the care of patients in PC. To prevent complications and its needed to initial the dentist as early as possible as a multidisciplinary member. It has been suggested palliative care protocol based on the up to date literature available for some frequent oral complications in TP with cancer. Other complications in terminal patients and their treatments still need to have further studying.

Core Tip: Palliative care aims to improve quality of life in patients in terminal diseases, through suffering’s prevention and relief. It is the duty of the dental surgeon to possess the knowledge needed to treat them. This integrative review aimed to synthesize the published evidence on oral conditions and their management among palliative patients. The most prevalent oral manifestations in end-stage cancer patients are xerostomia, oral candidiasis, dysphagia, dysgeusia, oral mucositis, and orofacial pain. Information on the behavior of oral manifestations and their treatments is lacking and there is little participation of the dental community. Also, updated protocols should be stablished. Palliative care, oral lesion, terminal patients Palliative care, oral lesion, terminal patients.

- Citation: Silva ARP, Bodanezi AV, Chrun ES, Lisboa ML, de Camargo AR, Munhoz EA. Palliative oral care in terminal cancer patients: Integrated review. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(13): 2966-2980

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i13/2966.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i13.2966

The World Health Organization (WHO), in its concept updated in 2002, defines palliative care (PC) as "an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families, in the face of problems associated with life-threatening diseases, through prevention and relief of suffering, early identification, impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other physical symptoms, spiritual, psychological and social"[1].

In the final stage of life the human being becomes physically and psychologically vulnerable and for this reason requires constant care. Despite science evolution, most areas of medicine still encounter many difficulties to adequately care terminal patients. As stated in the Venice Declaration adopted by the 35th General Assembly of the World Medical Association in 1983, "the duty of the physician is to heal and when this is not possible, alleviate suffering and act in the protection of the best interests of his patient"[2].

Palliative care guarantees the best possible quality of life for the patient, according to their values, needs and preferences, in order to comfort him and his family. Such care must be interdisciplinary not only to reduce pain and other symptoms from the disease, but also to provide emotional support[3].

The latest WHO data shows that cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020, with an incidence of 18094716 new cases of neoplasms that year[4]. According to McDonnell and Lenz, 2006 75%-99% of person who underperforms chemotherapy will present adverse oral effects, such as oral mucositis[5].

The treatments of oral complications are crucial for maintaining comfort, feeding and phonation, since the most prevalent oral manifestations in terminally ill cancer patients are: mucositis, stomatitis, nausea, vomiting, candidiasis, nutritional deficiency, dehydration, taste impairment and xerostomia[6].

To date, there is scarce evidence on the preventive and therapeutic measures to be performed by dentists in terminal patients. Within the studies of the palliative care, the areas of medicine, nursing and physiotherapy are more frequent as can be seen in the manual written by WHO[7].

Nevertheless, dentists should be familiar with dental treatments of terminal patients to define appropriate actions and to cooperate with other health professionals to contribute to patients’ well-being.

This integrative review aimed to synthesize the published evidence on oral conditions, impact, management and challenges in managing oral conditions among palliative patients.

This integrative review was conducted utilizing the five steps outlined by review guidelines Souza et al[8], Sladdin et al[9]: (1) Problem identification: "What oral manifestations are present and what dental interventions are indicated for patients diagnosed with end-stage cancer?"; (2) Literature search: The search keys and databases were defined. PubMed, Scopus databases and also selected articles found in the reference lists are used. The search strategy applied was: ("palliative care"[All Fields] OR "end of life care"[All Fields] OR "palliative medicine"[All Fields] OR "terminal patients"[All Fields]) AND ("oral health"[All Fields] OR "dental health"[All Fields] OR "dental"[All Fields] OR "oral complications"[All Fields]OR "oral treatments"[All Fields] OR "oral lesions"[All Fields] OR "oral diseases"[All Fields] OR "dentistry"[All Fields] OR "oral management"[All Fields] OR "dental care"[All Fields] OR "oral infections"[All Fields] OR "oral care"[All Fields] OR "special care dentistry"[All Fields] OR "oral interventions"[All Fields] OR "bucal management"[All Fields] OR "dental management"[All Fields] OR "bucal treatments"[All Fields] OR "dental treatments"[All Fields]) AND ("oncology"[All Fields] OR "cancer"[All Fields] OR "neoplasms"[All Fields]). To remove duplicate articles, Endnote web software was used; (3) Data evaluation: Based on the abstracts, a reviewer (ARPS) selected the full- text articles that met the following inclusion criteria: published in English, Portuguese or Spanish, systematic review articles, cross-sectional, longitudinal studies and clinical trials published up to 2022, which brought information about oral care in terminal cancer patients. Exclusion criteria were case reports, literature review articles, theses, dissertations and articles focusing on the quantity or quality of health professionals; (4) Data analysis: Two researchers (ARPS and ESC) read in full the previously selected articles and included those that met the previously established criteria, independently. In case of disagreement, a third researcher was consulted to define or not to include the article. Items included in the table: author(s), year of publication, objectives, study population and sample size (if applicable), metho

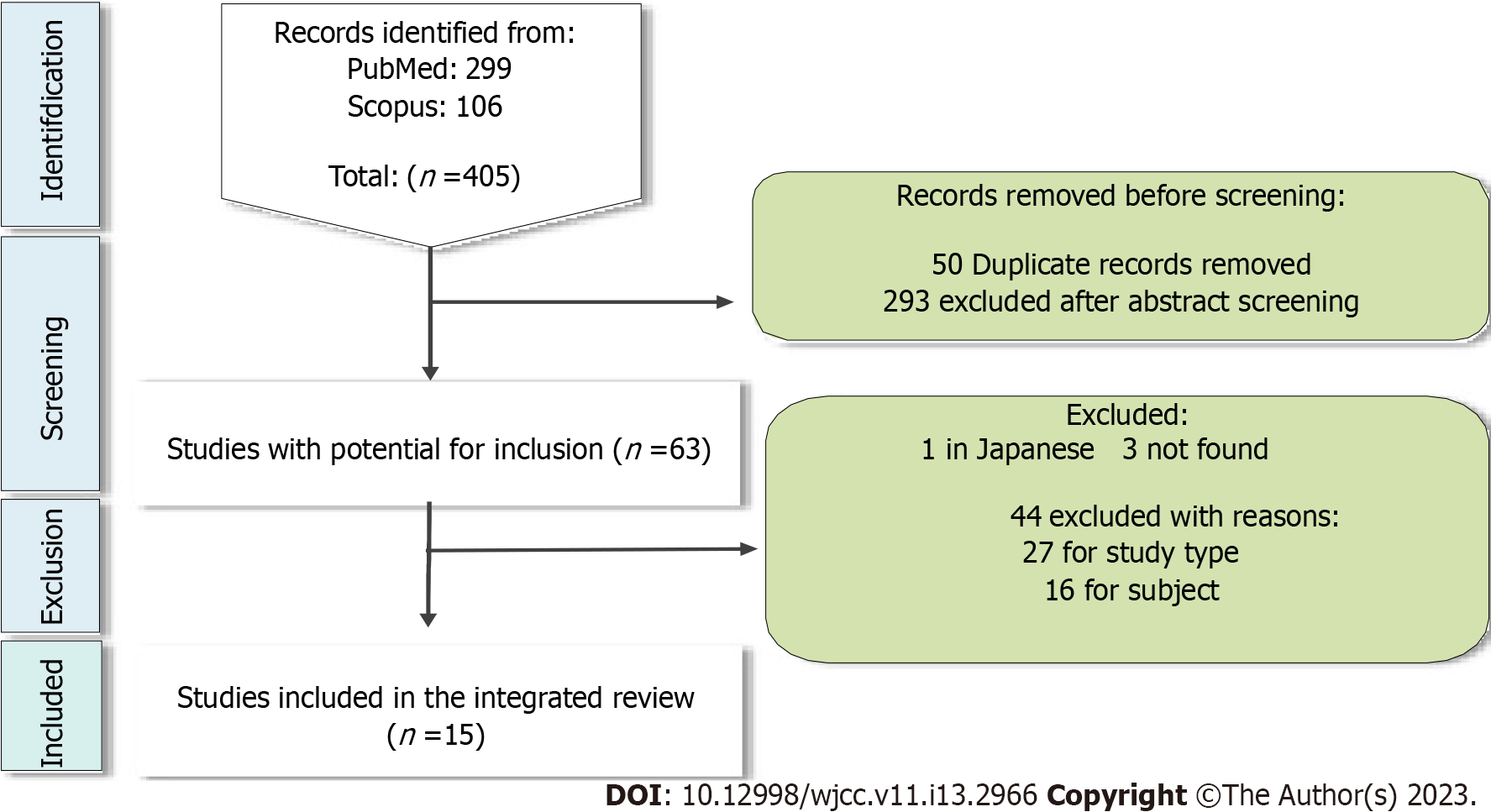

The search in the databases recovered a total of 405 articles (Figure 1). Of these, 49 were duplicated and 293 were excluded because abstracts did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the 63 articles with potential for inclusion, one was excluded because it was in Japanese and 3 could not be recovered by physical and digital means, leaving 59 articles. There was doubt in 1 abstract, which was excluded after a third expert analysis and discussion with the reviewers.

Of the 58 articles remaining and read in full, 27 were excluded because they were in disagreement with the inclusion criteria, 16 were excluded because they were not related to dentistry and 1 article was excluded because it was repeated (Figure 1).

Of the 15 articles included (summarized in Table 1), Gillam et al[10], was based on qualitative analysis and the other 14 articles were based on quantitative analysis being 13 (92.8%) clinical trials[11-23] and one observational study[24].

| Ref. | Country | Title | Type | Category | Objective | Method | Sample | Results | Summary |

| Gillam et al[10], 2006, United Kingdom | United Kingdom | The assessment and implementation of mouth care in palliative care: a review | Systematic review | Manegement | Review existing literature published between 95 and 99 to determine whether oral care was effectively implemented in the configuration of palliative care | On a nursing basis (CINHAL), they found 11 articles (does not make clear the descriptors) | 11 articles | Studies with different tools used to view oral health and many studies report lack of training of nurses (72% of nursing colleges do not teach written oral evaluation methods) | The need for physicians and nurses to have a basic knowledge about diseases and oral care, but no study speaks as. It is important to have an evaluation tool |

| Wilberg et al[11], 2012, Norway | Norway | Oral health is na important issue in end- of-life cancer care | Croos-sectional | Oral manifestation | Investigate the prevalence of oral and dental problems in cancer patients receiving palliative care. Specifically, it was to examine oral health and prevalencia of oral morbidity through patient reports and oral examination. Also investigating information related to oral problems was received by patients | First the interview was done through a symptom reporting tool, and then a clinical oral examination and oral mucosa swab collection. If candidiasis was confirmed, treatment was given | 99 patients | Average age 64, 47% men, cancer GI 21%, lung 19% prostate. 11%. 50.5% caries. Change of palate 68%, while 56% had problem eating, xerostomia 78% and 41% for + 3 months, 70% increase in friction in mirror test, general oral discomfort 67%. No significant difference when commencing the remedies with the patients with the symptoms described. Microbiol evidence. 86%, 34% clinical and biolog. 14% use prosthesis. Average lost teeth 5.7, 22% received information about adverse cancer effects, 38% how to reduce xerostomia | Microbiological evidence of candida in 86%, 34% clinical and biological. The 9 under treatment still had (uncertain effect). 22% received information on adverse effects of cancer, 38% of how to reduce xerostomia and 31% of the importance of oral hygiene (little, but satisfied). Alt. taste and xerostomia significantly related to oral morbidity (general discomfort). Caries largest number |

| Davies et al[12], 2008, United Kingdom | United Kingdom | Oral candidosis in community-based patients with advanced cancer | Croos-sectional | Oral manifestation | Determine the epidemiology, etiology, clinical and microbiological characteristics of oral candidiasis among community patients | Questionnaire, clinical examination, measurement of saliva production and swab collection of those who demonstrated clinical dinal of candidiasis. They isolated the collected species, if necessary, DNA sequencing | 390 patients | Mean age 73, 65% women, breast cancer 23%, bronchio and colon and prostata 11%. 70% had candida on microbionogic examination and 13% in microb. And in the clinician. 63% a species, 31% 2 species. C. albicans 75%. C.gabrata 2nd most frequent. Presence of candidiasis has not been associated with age, gender, or use of systemic antibiotic. 67% xerostomia. Presence of candidiasis associated with severity of xerostomia, use of corticosteroids, ECOG and dentures | In agreement with other studies: Candidiasis becomes more common in patients near death (ECOG), increases with the high severity of xerostomia, but not with the use of antibiotics. No agreement: association between candidiasis and the use of systemic corticosteroids |

| Oneschuk et al[13], 2000, Canada | Canada | A survey of mouth pain and dryness in patients with advanced cancer | Croos-sectional | Oral manifestation | Determine the prevalence of dry mouth and/or oral pain in patients with advanced cancer, and whether they were present, quantify the intensity of these symptoms, whether treatment was offered by the health team and which when symptoms were expressed, the author's main opinion on the cause of these symptoms and the relative importance to the patient compared to other symptoms or problems they experienced | 11-item questionnaire on oral pain and dry mouth and its intensity and importance of symptoms. Found from the oral examination were documented verbally and/or visually and the possible cause is documented | 99 patients | Average age 70, 58% women, lung cancer 28%, GI 27%. 16 of the 99 had oral pain, 10 of them in the gums, and the mean intensity was 5 on a scale from 0 to 10. 88% had dry mouth, with an average intensity of 6.3. 24% had dry mouth before cancer diagnosis and 31% pain. 28.2% saw the dentist after diagnosis. 56% mentioned pain for the caregiver and 44% for dry mouth. After reviewing the patients' medical documentation, only one of them had documented the pain complaint and 5 dry mouth complaints. Of the 44%, 69% received advice on treatment. Found most common were candidiasis and presence of denture | 88% dry mouth and 16% pain. Moderate importance in relation to other symptoms - more or less half of patients report their problems, and there are few documentations of these. The recommendations for dry mouth: drinking liquids, mouthwash with bicarbonate and use of oral antifungic. Only 1 of the 2 who had candida and pain were advised to use topical antifungic |

| Matsuo et al[14], 2016, Japan | Japan | Associations between oral complications and days to death in palliative care patients | Clinical trial | Oral manifestation | Investigate the association between the incidence of oral complications and DTD in patients in palliative care | They reviewed the reports and evaluations of oral conditions of terminal patients between April 2013 and March 2014. In the evaluation, clinical examination was taken and food intake was evaluated. Data from blood tests (leukocytes) for inflammation and DTD were evaluated. Divided into long and short DTD | 105 patients | Cancer pancreas/bile 18%, gastrointestinal tract (16%). Carie 16.3% in long, 10.7% short 13.3%T. Xerostomia 54% long and 78% short (significantly higher). Candida 10.7 and 10.2%, 10.4%T. Inflammation of the tongue, bleeding spots and dysphagia also (43% and 20%). Long group 50% requires oral care support and 76% in short (different). The more attention needed and more xerostomia, the shorter the DTD | Major problems when arriving near the day of death and the problems began to progress with the time of hospitalization. Xerostomia, inflammation of the tongue, bleeding spots and dysphagia |

| Bagg et al[15], 2003, Glasgow | Glasgow | High prevalence of non-albicans yeasts and detection of anti- fungal resistance in the oral flora of patients with advanced cancer | Croos-sectional | Oral manifestation | Examine in detail the oral mycological flora in a wide range of patients with advanced cancer, receiving care in three different centers | Collected demographic details and therapy information, examination of the oral cavity by a qualified dentist and collection of a tongue swab, subsequently inoculated and incubated | 207 patients | Average age 67.9, 45% men, lung cancer 18%, breast 16%, oral 5%. 81% denture, 50% edentulum. 48% with clinical evidence of xerostomia, 26% candida. No difference between denture use and fungic infection. 22% had antifungic treatment. 65% of the isolates had 1 species, 30% 2, 5%. 3. 47% with heavy density. 79%. C. albicans. 71% fluconazole, 55% for itraconazole. resistance-related xerostomia | Most of the isolates were of C. albicans in cancer patients (previous exposure to fluconazole?). By the use of immunosuppressants and antifungics, C. glabrata is now a pathological and more resistant species |

| Burge et al[16], 1993, Canada | Canada | Dehydration symptoms of palliative care cancer patients | Croos-sectional | Oral manifestation | Determine the severity and distribution of symptoms associated with dehydration in hospitalized palliative care patients and determine the association between the severity of these symptoms and commonly used dehydration measures. | Patients completed two questionnaires, 24 h apart. The nurses took the questionnaire as well. A blood sample was collected in the 24-h interval (sodium, urea and osmolarity). They measured how much liquid they ingested | 52 patients | Average age 64.4, 50% women, gastrointestinal cancer 27%, lung 27%. Oral diseases and survival were not related. No association was found in the multivariate analysis. You can't list the meds.Fatigue was the most reported symptom. Patients who reported head and other symptoms also reported dry mouth and bad taste in the mouth (most). It's not a blind study, so it has this bias. Longer survival time is associated with less thirst | Most patients had symptoms of thirst. It's not a blind study, so it has this bias. Fatigue was the most reported symptom. No association between thirst and variables. Clinics argue that the thirst and intake of liquids decrease near death. However, longer survival time is associated with less thirst |

| Fischer et al[17], 2014, United States | United States | Oral health conditions affect functional and social activities of terminally ill cancer patients | Croos-sectional | Oral manifestation | To characterize oral diseases in patients with end-stage cancer in palliative care to determine the presence, severity, and social/functional impact of oral diseases, which affect quality of life | Questionnaire on xerostomia, taste change, orofacial pain and impact of diseases. "Self-report" and oral clinical examination | 104 patients | 29% between 50-64 yr, 59% women. 98% had salivary dysfunction and 60% had moderate to severe dysfunction. Erythema 50%, ulceration 20%, fungic infection 36%. Xerostomia was a frequent and moderate complaint. Ulcers associated with the presence of orofacial pain and social impact. Xerostomia, change in taste and orofacial pain associated with social impact. Hyposalivation associated with social and functional impact | Hyposalivation has a social and functional impact and is a frequent complaint with moderate severity. Orofacial pain and change in taste has social impact. Presence of fungic infection similar to other studies |

| Sweeney et al[18], 1998, United Kingdom | United Kingdom | Oral disease in terminally ill cancer patients with xerostomia | Croos-sectional | Oral manifestation | Descreve sinais e sintomas orais de um grupo de pacientes com cancer terminal, todos com xerostomia, os quais foram subsequentemente tratados com um substituto salivar em spray | Pacientes que relataram consecutivamente boca seca para o staff. Questionario, sintomas registrados por escala analogica visual 0-6, exame bucal visual e coleta de cultura da língua e assoalho e quantidade de saliva | 70 patients | Mean age 66, 64% men, lung and breast cancer, 2.8% oral. 10% caries. 90% evidence xerostomia clinic, 9% C. pseudom sign.97% reported by day and 84% at night, 66% speech difficulty, 57% taste change, 51% difficulty eating, 31% pain. 40% of the prosthesis users had a problem with it. 65% had mucosal abnormalities, of these 20% erythema and 20% lingual saburra. C. albicans more common and C. glabrata 2nd most common | 66% speech difficulty, 57% change in taste, 51% difficulty eating, 31% pain. 67% of the patients had fungic disease in the isolates. Good hygiene. S. aureus 26% suggested cause of mucositis, as well as coliforms (19%). Herpes was relatively low |

| Xu et al[19], 2013, China | China | Investigation of the oral infections and manifestations seen in patients with advanced cancer | Croos-sectional | Oral manifestation | To investigate the focus of oral infections between cancer groups and treatment methods, in addition to describing and comparing epidemiology, independent risk factors | Data collection, oral examination and oral cavity swab collection for microbiological isolation | 850 patients | Average age 48, 57% men, cancer GI 17%, hematological 15%, 13% head and neck. Oral infections 46%, of these 52% with candidiasis (72% had fungal colony), 20.5% mucositis, 15.4% herpes. A logistic regression analysis showed that malnutrition and prosthesis use are independent risk factors for oral infection.Head and neck cancer had more infections and hematologic the second. Chemo and radiotherapy had higher infection | Candidiasis more prevalent, followed by mucositis. Disparity in oral infection data in these patients (various possible reasons). Head and neck cancer and hematologic. Prosthesis and nutrition are risk factors |

| Thanvi et al[20], 2014, India | India | Impact of dental considerations on the quality of live of oral cancer patients | Croos-sectional | Quality of live | Understand the role of the dentist and the impact on quality of life in a patient with oral cancer in a palliative care unit | History of oral cancer treatment, clinical examination and quality of life questionnaire | 50 patients | 64% women. Age measured 57. All oral cancer. 98% of the patients had some deleterious habit, 58% smokers. 12% had information before therapy. 74% had sensitivity and 50% limitation in mouth opening (evaluated root carie, atrition and sharp cuspides). 78% worsened The QOL, of these only 2% had dental considerations | Dental treatment was not done in 76% of patients who had already undergone treatment, 2% received consideration. Mouth opening sensitivity and limitation (did not evaluate xerostomia, mucositis, but evaluated "sharp cusps", atrition and root caries). 78% worsened QOL |

| Bagg et al[21], 2005, United Kingdom | United Kingdom | Voriconazole susceptibility of yeasts isolated from the mouths of patients with advanced cancer | Croos-sectional | Treatment | Determine the susceptibility of voriconazole to a large collection of well-characterized fungal isolates from the oral cavity of patients with advanced cancer | 199 oral samples isolated from swab and oral rinse. Susceptibility test for fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole | 199 patients | Breast cancer, bronchio, prostata and large intestine. 270 yeast species, C. albicans 59%, C. glabrata 19%, C. dubliniensis 7%. 76% flucona, and 14% fluconazole resistant. Of the fluconazole resistant, 7 sensitive to itraconazole and 41 resistant. Of the 49 resistant to itraconazole, 41 was also fluconazole and 8 senseless. 15% resistant to fluconazole and itraconazole, mostly C. glabrata and C. albicans. C. glabrata was 54% of fluconazole resistant | Voriconazol é mais potente que fluconazol ou itraconazol contra leveduras isoladas de boca de pacientes com cancer avançado, e é mais potente com aqueles resistentes a fluconazol e itraconazol |

| Bagg et al[22], 2006, United Kingdom | United Kingdom | Susceptibility to Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil of yeasts isolated from the mouths od patients with advanced cancer | Croos-sectional | Treatment | Examine in vitro susceptibility to TTO from a collection of well-characterized yeasts, including azol-resistant strains isolated from the mouth of patients with advanced cancer | 301 Yeasts isolated and MIC measurement for TTO | 199 patients | Breast cancer, bronchio, prostata and large intestine. MIC 50 was 0.5% for C. albicans and C. dubliniensis and 0.25% for C. glabrata, C. tropicalis and S. cerevisiae. MIC 90 for C. albicans, glabrata and dubliniensis was 1%. All itraconazole and fluconazole resistant were susceptible to TTO at commercially available concentrations | Treatment should be considered a potent preventive or therapeutic agent of oral candidiasis in these patients. As a water-based filler or adjuvant the regular washing |

| Nakajima et al[23], 2017, Japan | Japan | Characteristics of oral problems and effects od oral care in terminally ill catient with cancer | Clinical trial | Treatment | Investigate oral problems in the terminal stage of cancer and improves through oral care focusing on dry mouth | Divided into good oral and bad intake (115A and 158B) to 30% for good. Incidence of dry mouth and its severity (0-3), stomatitis, candidiasis.Standard oral care for dry mouth by nurses (hydration, brushing and cleaning or massage), and therapy for dry mouth and stomatitis. Special care if it did not improve | 273 patients | Average age 62.4A and 66.2B, 144 men and 129 women. Lung cancer 38A 48B, Liver/bile/pancreas 18A 30B, Head and neck 5A 8B. Dry mouth 38.3%A 81%B 63%T. Stomatitis 10.4%A 16.5%B 13.9%T. Candidiasis 6.1%A 22.8%B 15.8%T. All with stomatitis and candidiasis had dry mouth. Severe dry mouth 20%A 64%B. Dry mouth treatment: grade 2 B needed specialist (85%A 83%B), grade 3 also (80%A 81%B) Overall improved 80% or more | B significantly higher than A: Dry mouth and candidiasis. Interventions improved 80% or more dry mouth. Importance of oral care before the problem worsens. Oral care is better than artificial hydration for dry mouth. The registration of oral conditions by staff is not 100% (limitations, improve) |

| Ezenwa et al[24], 2016, United States | United States | Caregiver's perspectives on oral health problems of end-of-life cancer patients | Cross-sectional study | Management | Describe caregivers' awareness of oral health problems, compare caregivers' problems with patients' problems and explore the influence of caregivers' socio-demographic characteristics on their awareness of oral problems | Caregivers and patients answered questionnaires separately. Caregivers and patients completed the scale of oral problems | 104 patients104 caregivers | Patients: 29-112, 29% between 50-64 yr, 59% women, Lung cancer 26%, colorectal 14%, head and neck 3%. 48% of caregivers(C) were not trained, 30% of c evaluated the problems only when necessary and 13% never evaluated. C underestimated xerostomia and overestimated the social impact. C with 65+ had lower accuracy in reporting the problems. C with health problem were less aware | 48% C without training. C underestimate xerostomia, but is aware of orofacial pain. No difference in race, gender, C's education |

Also among the included studies, 10 presented data on the site of origin of the tumour, being lung[13,15,18,23,24] and gastrointestinal tract[11,16,19,21] breast[18,22] and prostate[26] the most common. Five articles reported the prevalence of patients with head and neck cancer[15,18,19,20,24].

The prevalence of deleterious habits of patients was investigated in three studies[11,13,20].

Among the 15 studies included, only 3 aimed to analyze therapies for different oral diseases[21,22,23], while 9 analyzed the prevalence of different oral manifestations[11-19]. The objective of the remaining 3 studies was related to the quality of life of terminal patients[20] and the dental management of these patients[10,24].

The results found in the selected articles have a wide variety. A single article compared groups with long and short remaining life time[14].

Four studies reported the prevalence of caries disease in terminal patients[11,14,18,20] and only one investigated the prevalence of dental plaque in these patients[11]. Regarding the presence of teeth, only the articles by Bagg et al[15], and Davies et al[12], calculated the prevalence of edentulous patients. Wilberg et al[11], found that 69% of patients aged ≥ 60 years had a ≥ than 20 teeth. The presence of prosthesis was evaluated by Bagg et al[15], Davies et al[12], Sweeney et al[18] and Wilberg et al[11] (26.7% of the articles), with a prevalence of 81%, 57%, 80% and 14%, respectively.

A total of nine articles brought data on the prevalence of oral Candida species in patients with advanced stage cancer[11-19,23], seven of them approached microbiological analyses of the fungus[11,12,15,18,19,21,22] and three investigations evaluated susceptibility to different antifungals drugs[15,21,22].

Of the selected studies, seven involved analyses of microbiological isolates of the oral mucosa[11,12,15,18,19,21,22].

The percentage of patients with xerostomia was evaluated in 8 articles (Table 2)[11,12,13,14,15,17,18,23]. The only article that brought data on the type of treatment used for this condition was that of Oneschuk et al[13].

| Ref. | Xerostomia | Eat/Swallowing problems | Mucositis | Dysgeusia | Oral pain |

| Fischer et al[17], 2014 | 91 | 61 | - | 71 | 23 |

| Sweeney et al[18], 1998 | 90 | - | - | - | 31 |

| Oneschuk et al[13], 2000 | 88 | - | - | - | 16.1 |

| Wilberg et al[11], 2012 | 78 | 56 | - | 68 | - |

| Davies et al[12], 2008 | 67 | - | - | - | - |

| Matsuo et al[14], 2016 | 64.7 | 29.5 | - | - | - |

| Nakajima[23], 2017 | 63 | - | 13.9 | - | - |

| Bagg et al[15], 2003 | 48 | - | - | - | - |

| Xu et al[19], 2013 | - | - | 20.5 | - | - |

| Mean | 73.7 | 48.8 | 17.2 | 70 | 23.3 |

Table 2 presents ther variables also addressed in articles. Two studies reported, the prevalence of changes in taste or dysgeusia[11,17] and three evaluated problems when eating[11,14,17].

Facial pain and intraoral pain were addressed in three articles[13,17,18] whereas oral mucositis or stomatitis was reported in two studies[19,23]. Only Thanvi et al[20], investigated mouth opening limitation and only Xu et al[19], researched herpes simplex prevalence in terminal patients.

Fischer et al[17], also brings the prevalence of dysphagia (61%), dysgeusia (71%), facial pain (23%) and intraoral pain (52%)[17]. Oneschuk et al[13], and Sweeney et al[18], also studied oral pain, with a prevalence of 16.1% and 31%, respectively. In addition to these variables, Thanvi et al[20], obtained a 50% prevalence of patients with limited mouth opening, Xu et al[19], found 15.4% of patients with herpes simplex and 20.5% with oral mucositis, while Nakajima[23], 2017, obtained 13.9% of patients with stomatitis.

The only study based on qualitative analysis was a systematized review, published by Gillam et al[10], where 11 articles found in a nursing database were analyzed, published in 1995 and 1999. No demographic data was specified from the studies reviewed by Gillam et al[10].

From the results obtained, it was observed that the single study based on qualitative analysis had nurses providing oral care to palliative patients[10]. It should also be emphasized that four of the published articles were written by professionals from other health areas[10,13,16,23]. The scarcity of investigations involving dentists demonstrates that this professional is not currently part of most teams that care for terminally ill patients. There seems to be a vast field of action for which dentists should be qualified. From the moment a dentist becomes part of the healthcare hospital team there happens an improvement of 37.25% in the accuracy of diagnosis of oral lesions[25].

Given that most studies analyzed were cross-sectional and not longitudinal, it makes impossible to gather information on the evolution of oral manifestations and therapeutic responses over time[11-22,24].

Demographically, the majority of the patients studied were women with a mean age of 63.8 years and diagnosed with lung and gastrointestinal tract cancer and for this reason special attention is needed for the diagnosis of oral lesions in this specific audience[11-13,15-20,23,24].

As most studies were published between 2006 and 2016, it can be inferred that dental treatment and management in PC among PT is a subject considered recent and constantly growing, which justifies the scarcity of qualified data found on the topic in the literature[10,12,14,17,24].

Most studies used the questionnaire tool[11,12,13,16,17,18,20,24], either to obtain demographic information[20] or to record symptoms of patients[11,13,16-18] and caregivers' opinions[24]. Such a tool can be useful even to record the symptoms of PT by caregivers, besides being a complement to oral examinations performed, either by caregivers or researchers.

Oral candidiasis: The prevalence of candidiasis in the oral mucosa of patients under palliative care [11] was investigated in nine of the selected articles[12-15,17-19,23]. The mean prevalence of oral candidiasis presented in those was high when compared to the mean detected for the healthy population (2% to 14%)[26]. Oral candidiasis is a frequent disease in systematically compromised patients, such as patients with end-stage cancer. Which reflects that more knowledge is still needed about the diagnosis and treatment of this disease in PT.

Mothibe et al[27] suggested that patients using prosthesis with cancer have a higher capacity for growth of oral candida. However, Bagg et al[15], found no associations between the use of prosthesis and the presence of oral candida in terminal patients. Another interesting finding was that the presence of oral candida seems to be related to the low food intake by patients[23].

On the microbiology of the oral cavity of palliative patients with cancer, the presence of C. albicans was identified in 58.2% of the patients included in the seven studies analyzed whereas C. glabrata was present in 24.5%[11,12,15,18,19,21,22]. Although the second most prevalent species in oral fungal infections, C. glabrata is not susceptible to certain antifungals[21,22].

The most prevalent oral candidiasis were erythemenous candidiasis and acute pseudomembranous candidiasis[12,15]. Erythemate candidiasis was prevalent in patients who used removable prostheses. Since a high percentage of palliative patients uses removable oral prostheses[11], it is important that patients and/or caregivers make the correct and regular hygiene of both the oral cavity and prostheses to prevent prosthetic stomatitis[15,18].

Pseudomembranous candidiasis of multifocal type was reported in 48% of patients investigated being the oral/jugal mucosa (48%) and the tongue (44%) the most affected sites[12,15].

A positive association was found between hyposalivation and oral candidiasis [12]. The hypofunction of the salivary glands can decrease the function of superficial cleansing of saliva, decrease its antifungal activity (because it decreases the amount of enzymes such as histatins and lysozymes) and reduce the pH of saliva which favors the proliferation of candida in the mouth.

About 75% of fungi were susceptible to fluconazole[21] and for this reason it will likely continue as the first treatment option. 53% of the isolated C. glabrata was resistant to fluconazole and also presented a low rate of therapeutic response to voriconazole[15,21] usually effective on more resistant candida species[21]. These results are in agreement with those of Wilberg et al[11], where 27% of patients undergoing antifungal treatment still had clinical signs of the disease.

Regarding the form of prescription of fluconazole, the latest cutting-edge research results state that the administration of daily doses of 100 to 200 mg can be recommended[28,29], and dose adjustment is needed for a renal patient[30] (Table 3). The susceptibility of fungi to melaleuca oil with positive results was also studied, concluding that this agent should be considered as a potential preventive agent and can be used as an adjuvant to oral hygiene[22].

| Oral complications | Therapeutical measures |

| Oral candidiasis | Fluconazole: 100 to 200 mg/d |

| In case of resistance: Itraconazole or variconazole and mouth rinsing with melaleuca oil after oral hygiene | |

| Xerostomia | Daily and frequent water sip intake |

| Artificial saliva use | |

| In severe cases: Discuss the possibility of replacing causative drugs | |

| Dysgeusia | Discontinues 10 mo after antineoplastic therapy, on average |

| In severe cases: Discuss the possibility of replacing causative drugs | |

| Mucositis | Cryotherapy: Ice stones and ice cream kept in mouth decrease risk of mucositis and relieve pain (prescription according to chemotherapy) |

| Low-level laser therapy | |

| Cold chamomile-based tea solutions |

Xerostomia and hyposalivation: Dry mouth sensation in patients with end-stage cancer was the second most frequent complication reported in studies[11-15,17,18,23]. The prevalence of xerostomia in palliative patients ranged from 91% to 48% (Table 2)[15,17], indices relatively high when compared to those of normal population (0%-30%)[31,32]. Matsuo et al[14], observed that palliative patients with a short life expectancy had a significantly higher prevalence of xerostomia than those with longer life estimative. Adverse effects of drugs used to reduce pain such as opioids could justify those high indices[17]. Interestingly, only 22% of patients received information about xerostomia as an adverse effect of the drugs used in antineoplastic therapies [17]. In severe cases, the dentist should discuss with the doctor the possibility of replacing the medications that cause this symptom[23].

Hyposalivation has also a significant association with the functional and social impact of patients as well as low food intake[17]. Improving dry mouth sensation can thus help with other oral problems[23]. The adequacy of oral hygiene improves dry mouth symptom regardless of the degree of food intake[23] but only 31% of patients were informed about the importance of oral hygiene[23].

Despite being a frequent complication, patients classified xerostomia as of moderate importance when compared to other symptoms experienced at that palliative moment[13]. In the study of Oneschuk et al[13], about half of the patients (56%) who reported xerostomia also reported the symptom to the doctor and of these only 69% were advised to seek one or more treatments for symptom relief. Patients may believe that this information is of no clinical importance, that there is no need to treat it or that treatment options are limited.

The recommended treatments for xerostomia are to drink frequently sips of water and to use artificial saliva in spray[13] (Table 3).

Caries and plaque: In the only study on the topic included in this review, 24% of patients presented with moderate or severe amount of visible plaque[11]. Consumption of easy-to-chew carbohydrates (dietary supplement) and cognitive restrictions to perform adequate oral hygiene contribute to plaque accumulation. Besides, hyposalivation increases the tooth's susceptibility to demineralization.

Patients closer to death need greater help with oral care and that the inability of self-care is an indicator for the caregiver to perform oral hygiene properly. Matsuo et al[14], found a positive correlation between caries incidence and the number of days of life remaining. Poor oral hygiene is associated with oral diseases including caries and periodontitis. Teeth with active caries may cause pain and discomfort in the terminal phase of life, hindering feeding and compromising well-being.

This demonstrates the necessity to improve the quality and frequency of oral hygiene, within the limits of the patient's hematological parameters, as well as therapeutic measures to stop cavities progression and to preserve teeth function[33].

The prevalence of caries and plaque in the mouth of the patients studied was addressed in a few articles and it was not determined what posture should be taken in front of these cases, requiring to determine to what extent the dentist should intervene and perform the treatment of these cases[11,14,18,20].

Dysphagia: Difficulty in swallowing seems to be a comorbidity less prevalent than poor oral health among patients with terminal-stage cancer[34]. Wilberg et al[11], however, described a significant relationship between the patient's feeding difficulties and their perception of oral morbidity.

The cause of dysphagia in patients with advanced cancer is different from that found in neurological diseases or strokes, as there is a decrease in muscle volume due to malnutrition or cachexia[14].

Dysphagia was significantly more prevalent in patients with a short life time[14], and may be considered a strong criterion of palliactive care necessity[14,17]. Fischer et al[17], observed a prevalence of “swallowing problems” almost three times higher than that of Matsuo et al[14]. In contrast, Furuya et al[35], described that the swallowing function was relatively well-conserved and 46.3% of the participants were capable of nutrition intake solely by mouth[35].

In the study of Furuya et al[35], more than half of the participants did not wear their removable dentures despite needing them. Wearing removable dentures improves the ability to masticate and facilitates the swallowing of food. Dentists have a key role in palliative care in terms of supporting nutritional intake via dentures[35].

In addition to the absence of teeth and incompatibilities of removable prostheses, reduction of saliva and diseases such as candidiasis and mucositis could also be related to dysphagia[23,36].

The treatment of dysphagia is still a challenge. More recent studies show that exercises can improve dysphagia symtoms[37] and that electrical stimulation has not brought benefits[38].

Hypogeusia and dysgeusia: Changes in taste are extremely common in cancer palliative patients due to the adverse effects of drugs such as keratolytic agents, chemotherapeutic and cancer medication, antihistamine, antibiotics and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, analgesics, bisphosphonates and antidepressants[11,39]. The study by Wilberg et al[11], stated that the change in taste is related to higher oral morbidity.

In the two articles included, taste changes were reported by 62%[11] and 78% of individuals[17]. This complication can have a great influence on oral function and, consequently, on the nutritional status and quality of patients’ life.

Dentists can help alleviate this symptom through identification, discussion with the multidisciplinary team, oral hygiene improvement and prescription of potential therapies such as anti-xerostomia agents and photo biomodulation[40].

Orofacial pain: Orofacial pain is a concern that affects social interaction of palliative patients and interferes with their quality-of-life[17]. The mean number of patients that reported orofacial pain in the studies included was 23.3% to orofacial and 52% to intraoral pain[17].

Ten of the 16 terminal patients included in the study by Oneschuk et al[13], complained of localized pain in the gums. Although the gum may be a painful oral site, oral cavities and prostheses incompatibilities were not examined by a dentist to rule out potential sources of referred pain.

No studies were found on the treatment of orafacial pain in terminal patients, however the subject is widely studied in patients in general. Up to date studies shows several therapies reported, among them counseling therapy; occlusal appliances; manual therapy; laser therapy; dry needling; intramuscular injection of local anesthesia (LA) or botulinum toxin-A (BTX-A); muscle relaxants; hypnosis/relaxation therapy; oxidative ozone therapy; and placebo[41].

Oral mucositis: Oral mucositis is an acute and painful side effect of antineoplastic therapies (chemotherapy and head and neck radiotherapy). It affects non-ceratinized surfaces such as the entire gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by pain, ulceration and difficulties in feeding and phonation[42].

In the two studies included on the subject, 17.2% of the patients investigated had mucositis[19,23]. This incidence is lower than that found for mucositis during chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment probably because these therapies are often interrupted when the patient are in palliative care. These authors, also, did not relate the type of antineoplastic therapy (radiotherapy or chemotherapy) to the prevalence of mucositis and, for this reason, the toxicity of these therapies in the oral mucosa could not be analyzed. In the study by Xu et al[19], chemotherapy in conjunction with radiotherapy were associated with a higher prevalence of oral infections in general (68.4%) compared to chemoterapic (52%) or radiotherapy (53.9%) treatments in an isolated way[19].

Pain caused by mucositis is poorly tolerated by patients and is accentuated especially during the act of food intake[42]. The lack of information on this complication in the selected articles is worrisome because in addition to its prevalence being relatively high, the pain caused is poorly tolerated by patients and the reduction of this symptomatology should be studied more deeply.

In the literature there are many studies on mucositis during cancer treatment or during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation[43,44], however, there is a gap in the literature when it comes to respective therapeutic oncological PT.

With regard to oral mucositis in particular, we found that cryotherapy, where the patient makes the use of ice stones, ice cream or ice cream in the oral cavity 5 min before and 30 min after chemotherapy or longer periods, can contribute to the reduction of the degree of oral mucositis and the time of pain caused by the lesions[45,46]. In addition to cryotherapy, on recent studies, researchers recommend the use of low-power laser therapy, photodynamic therapy, honey, the use of chamomile tea as a mouthwash with good results[47-53].

Professionals involved in the treatment of terminally ill cancer patients are the key to establishing adequate oral health care[24]. In a hospital setting will be cared for by nurses and other health professionals, ideally including a dentist on the team. However, if you live with family members in a permanent care home, the nearest caregiver may be a family member or person hired by the family[10,24]. In the study by Ezenwa et al[24], 79% of the caregivers were family members, most of them women (77%) aged between 50 and 64 years (46%)[24] and only 48% became caregivers from formal training. Furthermore, more than half of the caregivers interviewed in the study reported that the patient's oral hygiene is one of the functions under their responsibility and of these, 81% mentioned the importance of this task in detecting potential oral problems developed by the patient. However, 30% of the caregivers examined the oral cavity only when necessary and 13% had never questioned the patient about possible oral problems. Furthermore, through the responses obtained from caregivers and patients, xerostomia was evaluated less frequently, suggesting that this symptom is underestimated by caregivers[24].

Gillam et al[10], reviewed 11 articles and 7 of them highlighted the lack of training and education of nurses[18,54-59].

Most nursing courses do not adequately teach oral health care, which reflects the lack of training of nurses working in CP centers. The training of oral hygiene techniques performed by dentists for caregivers can improve the quality of care offered, the speed in the diagnosis of oral alterations and the response to patient complaints

Determining a protocol for the care of these and other complications of cancer – or cancer therapy – based on scientific evidence with the latest cutting-edge research results is of fundamental importance for the multidisciplinary team that works in the care of patients in PC. The protocols used in the articles included in this review were not standardized, a fact that hindered the analysis, interpretation of discussion of the data analyzed by this study. The authors summarized on Table 3 the Suggested palliative care protocol based on the up to date literature available for some frequent oral complications in TP with cancer.

The care of patients under PC should not be neglected by professionals in this area, it should be treated seriously for us dentists, to be more effective in care.

Based on the information obtained and all aspects discussed, it is noted that the literature is still scarce when it comes to oral manifestations in terminal cancer patients under CP. Data such as the prevalence of mucositis, orofacial pain, dysgeusia and dysphagia were addressed in a few articles of the review, and a better evaluation is needed to determine the real prevalence of these diseases.

As a consequence, the treatment of mucositis, dysgeusia, dysphagia and oral pain should be studied in depth in PT.

Finally, it can be obtained through this integrative review that the most prevalent oral manifestations in end-stage cancer patients are xerostomia, oral candidiasis, dysphagia, dysgeusia, oral mucositis, and orofacial pain.

The information on the behavior of oral manifestations and their treatments in patients under palliative care, especially in the long term, is lacking and there is little participation of the dental community in research on the subject and training of caregivers of terminal lye patients under palliative care. Dentists can be helpful on alleviate the symptom of these oral manifestations in TP, improving the quality of live in these final days.

Resume the scientific evidence on oral conditions among palliative patients and its management.

Update the dentist for diagnosis and treatment of oral complication in a multidisciplinary palliative care team.

Synthesize the published evidence on oral conditions, impact, management and challenges in its managing among palliative patients.

Integrative review.

The total of 15 articles were eligible, analyzed and a protocol established.

Oral manifestations are, oral candidiasis, dry mouth, dysphagia, dysgeusia, oral mucositis and orofacial pain. Determining a protocol for the care, based on scientific evidence, is fundamental for the multidisciplinary team that works in the care of terminal patients.

Other complications in terminal patients and their treatments still need to have further studying.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dasuqi SA, Saudi Arabia; El-Gendy HA, Egypt S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | WHO. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. WHO. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. |

| 2. | WMA. The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Venice on Terminal Illness. 2017. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies- post/wma-declaration-of-venice-on-terminal-illness/. |

| 3. | American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; Center to Advance Palliative Care; Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association; Last Acts Partnership; National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for quality palliative care, executive summary. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:611-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | WHO. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Estimated number of new cases in 2020, World, both sexes, all ages (excl. NMSC). Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-table?v=2020&mode=cancer&mode_population=continents&population=900&populations=900&key=asr&sex=0&cancer=39&type=0&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=0&ages_group%5B%5D=17&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=0&include_nmsc_other=1. |

| 5. | McDonnell AM, Lenz KL. Palifermin: role in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiation-induced mucositis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wiseman M. The treatment of oral problems in the palliative patient. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72:453-458. [PubMed] |

| 7. | WHO. Palliative care: Symtom mamagement and end of life care. Gnova: World Helh Organization 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/imai/primary_palliative/en/. |

| 8. | Souza MT, Silva MD, Carvalho Rd. Integrative review: what is it? Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2010;8:102-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sladdin I, Ball L, Bull C, Chaboyer W. Patient-centred care to improve dietetic practice: an integrative review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30:453-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gillam JL, Gillam DG. The assessment and implementation of mouth care in palliative care: a review. J R Soc Promot Health. 2006;126:33-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wilberg P, Hjermstad MJ, Ottesen S, Herlofson BB. Oral health is an important issue in end-of-life cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:3115-3122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Davies AN, Brailsford SR, Beighton D, Shorthose K, Stevens VC. Oral candidosis in community-based patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Oneschuk D, Hanson J, Bruera E. A survey of mouth pain and dryness in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:372-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Matsuo K, Watanabe R, Kanamori D, Nakagawa K, Fujii W, Urasaki Y, Murai M, Mori N, Higashiguchi T. Associations between oral complications and days to death in palliative care patients. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:157-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bagg J, Sweeney MP, Lewis MA, Jackson MS, Coleman D, Al MA, Baxter W, McEndrick S, McHugh S. High prevalence of non-albicans yeasts and detection of anti-fungal resistance in the oral flora of patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2003;17:477-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Burge FI. Dehydration symptoms of palliative care cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8:454-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fischer DJ, Epstein JB, Yao Y, Wilkie DJ. Oral health conditions affect functional and social activities of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:803-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sweeney MP, Bagg J, Baxter WP, Aitchison TC. Oral disease in terminally ill cancer patients with xerostomia. Oral Oncol. 1998;34:123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Xu L, Zhang H, Liu J, Chen X. Investigation of the oral infections and manifestations seen in patients with advanced cancer. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29:1112-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thanvi J, Bumb D. Impact of dental considerations on the quality of life of oral cancer patients. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2014;35:66-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bagg J, Sweeney MP, Davies AN, Jackson MS, Brailsford S. Voriconazole susceptibility of yeasts isolated from the mouths of patients with advanced cancer. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:959-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bagg J, Jackson MS, Petrina Sweeney M, Ramage G, Davies AN. Susceptibility to Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil of yeasts isolated from the mouths of patients with advanced cancer. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:487-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nakajima N. Characteristics of Oral Problems and Effects of Oral Care in Terminally Ill Patients With Cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34:430-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Ezenwa MO, Fischer DJ, Epstein J, Johnson J, Yao Y, Wilkie DJ. Caregivers' perspectives on oral health problems of end-of-life cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4769-4777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Saleh HA, Lisboa ML, Flausino CS, Pilat SFM, Moral JAGD, de Andrade Munhoz E, de Camargo AR. The Practice of Hospital Dentistry in a Reference Hospital in Brazil. Int J Dent Oral Health. 2019;5:1-4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Martorano-Fernandes L, Dornelas-Figueira LM, Marcello-Machado RM, Silva RB, Magno MB, Maia LC, Del Bel Cury AA. Oral candidiasis and denture stomatitis in diabetic patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mothibe JV, Patel M. Pathogenic characteristics of Candida albicans isolated from oral cavities of denture wearers and cancer patients wearing oral prostheses. Microb Pathog. 2017;110:128-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Patil S, Rao RS, Majumdar B, Anil S. Clinical Appearance of Oral Candida Infection and Therapeutic Strategies. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Williams DW, Kuriyama T, Silva S, Malic S, Lewis MA. Candida biofilms and oral candidosis: treatment and prevention. Periodontol 2000. 2011;55:250-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yagasaki K, Gando S, Matsuda N, Kameue T, Ishitani T, Hirano T, Iseki K. Pharmacokinetics and the most suitable dosing regimen of fluconazole in critically ill patients receiving continuous hemodiafiltration. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1844-1848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | López-Pintor RM, Casañas E, González-Serrano J, Serrano J, Ramírez L, de Arriba L, Hernández G. Xerostomia, Hyposalivation, and Salivary Flow in Diabetes Patients. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:4372852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pina GMS, Mota Carvalho R, Silva BSF, Almeida FT. Prevalence of hyposalivation in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerodontology. 2020;37:317-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Paris S, Banerjee A, Bottenberg P, Breschi L, Campus G, Doméjean S, Ekstrand K, Giacaman RA, Haak R, Hannig M, Hickel R, Juric H, Lussi A, Machiulskiene V, Manton D, Jablonski-Momeni A, Santamaria R, Schwendicke F, Splieth CH, Tassery H, Zandona A, Zero D, Zimmer S, Opdam N. How to Intervene in the Caries Process in Older Adults: A Joint ORCA and EFCD Expert Delphi Consensus Statement. Caries Res. 2020;54:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Furuya J, Suzuki H, Hidaka R, Matsubara C, Motomatsu Y, Kabasawa Y, Tohara H, Sato Y, Miyake S, Minakuchi S. Association between oral health and advisability of oral feeding in advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:5779-5788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Furuya J, Suzuki H, Hidaka R, Koshitani N, Motomatsu Y, Kabasawa Y, Tohara H, Sato Y, Minakuchi S, Miyake S. Factors affecting the oral health of inpatients with advanced cancer in palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:1463-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Raza A, Karimyan N, Watters A, Emperumal CP, Al-Eryani K, Enciso R. Efficacy of oral and topical antioxidants in the prevention and management of oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:8689-8703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Greco E, Simic T, Ringash J, Tomlinson G, Inamoto Y, Martino R. Dysphagia Treatment for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer Undergoing Radiation Therapy: A Meta-analysis Review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101:421-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Langmore SE, McCulloch TM, Krisciunas GP, Lazarus CL, Van Daele DJ, Pauloski BR, Rybin D, Doros G. Efficacy of electrical stimulation and exercise for dysphagia in patients with head and neck cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Head Neck. 2016;38 Suppl 1:E1221-E1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Mortazavi H, Shafiei S, Sadr S, Safiaghdam H. Drug-related Dysgeusia: A Systematic Review. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2018;16:499-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sevryugin O, Kasvis P, Vigano M, Vigano A. Taste and smell disturbances in cancer patients: a scoping review of available treatments. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:49-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Al-Moraissi EA, Conti PCR, Alyahya A, Alkebsi K, Elsharkawy A, Christidis N. The hierarchy of different treatments for myogenous temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;26:519-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Volpato LE, Silva TC, Oliveira TM, Sakai VT, Machado MA. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73:562-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Lalla RV, Bowen J, Barasch A, Elting L, Epstein J, Keefe DM, McGuire DB, Migliorati C, Nicolatou-Galitis O, Peterson DE, Raber-Durlacher JE, Sonis ST, Elad S; Mucositis Guidelines Leadership Group of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer and International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO). MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer. 2014;120:1453-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 688] [Cited by in RCA: 731] [Article Influence: 66.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Herbers AH, de Haan AF, van der Velden WJ, Donnelly JP, Blijlevens NM. Mucositis not neutropenia determines bacteremia among hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sharifi H, Heydari A, Salek R, Emami Zeydi A. Oral cryotherapy for preventing chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis: An effective but yet neglected strategy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017;13:386-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Riley P, Glenny AM, Worthington HV, Littlewood A, Clarkson JE, McCabe MG. Interventions for preventing oral mucositis in patients with cancer receiving treatment: oral cryotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD011552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Legouté F, Bensadoun RJ, Seegers V, Pointreau Y, Caron D, Lang P, Prévost A, Martin L, Schick U, Morvant B, Capitain O, Calais G, Jadaud E. Low-level laser therapy in treatment of chemoradiotherapy-induced mucositis in head and neck cancer: results of a randomised, triple blind, multicentre phase III trial. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lai CC, Chen SY, Tu YK, Ding YW, Lin JJ. Effectiveness of low level laser therapy versus cryotherapy in cancer patients with oral mucositis: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;160:103276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Mazokopakis EE, Vrentzos GE, Papadakis JA, Babalis DE, Ganotakis ES. Wild chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) mouthwashes in methotrexate-induced oral mucositis. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:25-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tavakoli Ardakani M, Ghassemi S, Mehdizadeh M, Mojab F, Salamzadeh J, Hajifathali A. Evaluating the effect of Matricaria recutita and Mentha piperita herbal mouthwash on management of oral mucositis in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2016;29:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Pavesi VC, Lopez TC, Martins MA, Sant'Ana Filho M, Bussadori SK, Fernandes KP, Mesquita-Ferrari RA, Martins MD. Healing action of topical chamomile on 5-fluoracil induced oral mucositis in hamster. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:639-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | de Oliveira AB, Ferrisse TM, Basso FG, Fontana CR, Giro EMA, Brighenti FL. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of photodynamic therapy for the treatment of oral mucositis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2021;34:102316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Khanjani Pour-Fard-Pachekenari A, Rahmani A, Ghahramanian A, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Onyeka TC, Davoodi A. The effect of an oral care protocol and honey mouthwash on mucositis in acute myeloid leukemia patients undergoing chemotherapy: a single-blind clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23:1811-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Adams R. Qualified nurses lack adequate knowledge related to oral health, resulting in inadequate oral care of patients on medical wards. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24:552-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Andersson P, Persson L, Hallberg IR, Renvert S. Testing an oral assessment guide during chemotherapy treatment in a Swedish care setting: a pilot study. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8:150-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Dodd MJ, Larson PJ, Dibble SL, Miaskowski C, Greenspan D, MacPhail L, Hauck WW, Paul SM, Ignoffo R, Shiba G. Randomized clinical trial of chlorhexidine versus placebo for prevention of oral mucositis in patients receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996;23:921-927. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Ganley B. Mouth care for the patient undergoing head and neck radiotherapy: a survey of radiation oncology nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996;23:1619-23. |

| 58. | Longhurst RH. An evaluation of the oral care given to patients when staying in hospital. Prim Dent Care. 1999;6:112-115. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Ransier A, Epstein JB, Lunn R, Spinelli J. A combined analysis of a toothbrush, foam brush, and a chlorhexidine-soaked foam brush in maintaining oral hygiene. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18:393-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |