Published online Apr 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i12.2694

Peer-review started: November 22, 2022

First decision: February 14, 2023

Revised: March 1, 2023

Accepted: March 24, 2023

Article in press: March 24, 2023

Published online: April 26, 2023

Processing time: 154 Days and 20.1 Hours

Although conservative treatment is typically recommended for pregnant patients with pituitary adenoma (PA), surgical treatment is occasionally necessary for those with acute symptoms. Currently, surgical interventions utilized among these patients is poorly studied.

To evaluate the surgical indications, timing, perioperative precautions and postoperative complications of PAs during pregnancy and to provide comprehensive guidance.

Six patients with PAs who underwent surgical treatment during pregnancy at Peking Union Medical College Hospital between January 1990 and June 2021 were recruited for this study. Another 35 pregnant patients who were profiled in the literature were included in our analysis.

The 41 enrolled patients had acute symptoms including visual field defects, severe headaches or vision loss that required emergency pituitary surgeries. PA apoplexies were found in 23 patients. The majority of patients (55.9%) underwent surgery in the second trimester of pregnancy. A multidisciplinary team was involved in patient care from the preoperative period through the postpartum period. With the exception of 1 patient who underwent an induced abortion and 1 fetus that died due to a nuchal cord, 39 patients delivered successfully. Among them, 37 fetuses were healthy until the most recent follow-up.

PA surgery during pregnancy is effective and safe during the second and third trimesters. Pregnant patients requiring emergency PA surgery require multidisciplinary evaluation and healthcare management.

Core Tip: Although clinicians generally recommend conservative treatment for patients with pituitary adenomas (PAs), surgical treatment is occasionally necessary. Currently, surgical interventions utilized among these patients is poorly studied. This study investigated the surgical interventions utilized for patients with PAs occurring during pregnancy. We found that in the second and third trimesters transsphenoidal PA surgery is a safe and effective approach for emergency conditions arising during pregnancy and may be conducted after a multidisciplinary team evaluation. These strategies may open up new avenues for the treatment of PAs during pregnancy in the future.

- Citation: Jia XY, Guo XP, Yao Y, Deng K, Lian W, Xing B. Surgical management of pituitary adenoma during pregnancy. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(12): 2694-2707

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i12/2694.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i12.2694

Pituitary adenoma (PA) is the second most common primary brain tumor, accounting for 15% to 17% of brain tumors and 25% of benign brain tumors[1]. Although PAs can occur at any age, those occurring in pregnant patients have unique characteristics. Pregnancy can cause the enlargement of pre-existing PAs that may compress the meningeal, contributing to acute symptoms such as severe headache and visual defects. These symptoms can affect maternal health and fetal development[2]. In addition, hormone-secreting PAs may lead to increased levels of hormones, such as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), resulting in poor prognoses[1,3].

During pregnancy, some PAs can be controlled by conservative treatment. For example, patients with prolactinomas are treated with oral dopamine agonists (DAs)[1,4-6]. Although there is no evidence that somatostatin analogues (SSAs) are safe for the fetus during pregnancy, SSAs are effective in reducing tumor size and decreasing growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) levels in acromegaly[7,8]. However, some pregnant patients with acute compression symptoms, such as visual defects and severe headache, as well as non-prolactinoma patients with pathologically high hormone levels may accept surgical treatment in clinical practice. Surgical treatment may also be chosen if the problem cannot be solved by conservative treatment or potential side effects rule out pharmacological treatment. These patients pose a challenge to neurosurgeons in terms of surgical timing, surgical indications, anesthesia risk and perioperative treatment. At present, few case reports on the surgical treatment of pregnant PA patients are available, and adequate knowledge and experience regarding this surgical intervention are lacking.

The pituitary specialty at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) has a long history[9], and the Neurosurgery Department of PUMCH is the founding unit of the China Pituitary Adenoma Specialist Council and the China Pituitary Disease Registry Network. The endocrinology department at PUMCH is known as a leader in endocrinology[10]. In this study, we summarized the clinical presentation, imaging features, surgical indications, perioperative management and other vital considerations of 6 pregnant PA patients surgically treated at our hospital. We also included 35 similar patients reported in the literature. Our goal was to provide suggestions for the management of pregnant PA patients to physicians in neurosurgery, endocrinology, obstetrics/gynecology, ophthalmology, and other related specialties.

Six pregnant patients with PAs admitted to the neurosurgery department of PUMCH between January 1990 and June 2021 were retrospectively analyzed. All patients underwent surgery for PAs during pregnancy. The data collected included clinical symptoms, imaging features, perioperative treatment, pathological classification, and postoperative follow-up. All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

We performed a literature search using PubMed to identify relevant studies published between January 1990 and June 2021. Our search used the MeSH terms “pituitary adenoma,” “pregnancy” and “surgery.” Citation indices were used to expand the search for relevant studies. The search was limited to studies written in English and were included only when sufficient data were available. Some studies without details of cases, such as those describing clinical symptoms, imaging findings, surgical timing and specific pathology, were not included[11].

After reading and reviewing relevant literature, only patients with PAs who underwent surgery during pregnancy were included. Patients treated with conservative treatment alone as well as those who received treatment for pathological non-PA were excluded.

Patients with duplicate reports due to multiple articles published by the same clinical center at different times were manually removed. Based on the above criteria, 30 studies screened, resulting in the inclusion of 35 patients.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Measurement data conforming to a normal distribution were represented by. Enumeration data were expressed as percentages or ratios. Paired-sample t-tests were used for preoperative and postoperative comparisons. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Forty-one patients with PAs who underwent surgery during pregnancy were included. A summary of their clinical characteristics is provided in Table 1, which includes 6 cases from our center and 35 cases from the PubMed database. The ages of 3 patients were not reported. The age of the remaining 38 patients ranged from 21 years to 41 years, with a mean age of 29.7 ± 5.3 years.

| Data source | Case | Age, yr | Sex | Clinical symptoms | |||||||

| Headache | Vision loss | Visual field | OP | DI | HT | CS | Acromegaly | ||||

| Peking Union Medical College Hospital | 1 | 29 | F | No | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| 2 | 36 | F | Yes | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | No | |

| 3 | 34 | F | No | Bi | BTH | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 4 | 32 | F | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | |

| 5 | 37 | F | Yes | Mo | BTH | No | No | No | No | No | |

| 6 | 28 | F | Yes | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Jallad et al[16] | 7 | 25 | F | Yes | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 8 | 27 | F | Yes | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | Yes | |

| 9 | 27 | F | Yes | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Chaiamnuay et al[17] | 10 | 39 | F | Yes | No | UTH | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Guven et al[18] | 11 | 32 | F | No | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Zhong et al[38] | 12 | 29 | F | No | Bi | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Jemel et al[19] | 13 | 35 | F | Yes | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| 14 | 30 | F | Yes | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Xia et al[20] | 15 | 25 | F | Yes | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Yamaguchi et al[21] | 16 | 35 | F | Yes | Bi | UTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Tandon et al[22] | 17 | 27 | F | Yes | Mo | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Parihar et al[36] | 18 | 22 | F | Yes | Bi | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gondim et al[23] | 19 | 29 | F | Yes | Mo | UTH | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Witek et al[24] | 20 | 25 | F | Yes | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kita et al[25] | 21 | 26 | F | Yes | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Nossek et al[26] | 22 | 29 | F | No | Bi | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 23 | 34 | F | No | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Iuliano and Laws[27] | 24 | 28 | F | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 25 | 35 | F | Yes | Mo | UTH | Yes | No | No | No | No | |

| Hayes et al[28] | 26 | 41 | F | Yes | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Boronat et al[52] | 27 | 26 | F | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Abbassy et al[37] | 28 | 38 | F | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Coyne et al[53] | 29 | 22 | F | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Pinette et al[54] | 30 | 33 | F | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Ross et al[55] | 31 | 24 | F | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Mellor et al[51] | 32 | 40 | F | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Karaca et al[15] | 33 | NA | F | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Jolly et al[56] | 34 | 30 | F | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Galvão et al[29] | 35 | NA | F | Yes | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Abid et al[30] | 36 | 25 | F | Yes | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Barraud et al[31] | 37 | NA | F | Yes | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| Freeman et al[32] | 38 | 22 | F | Yes | Mo | BTH | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Lunardi et al[33] | 39 | 21 | F | Yes | Bi | BTH | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Oguz et al[34] | 40 | 26 | F | Yes | No | UTH | No | No | No | No | No |

| O’Neal[35] | 41 | 27 | F | Yes | No | BTH | No | No | No | No | No |

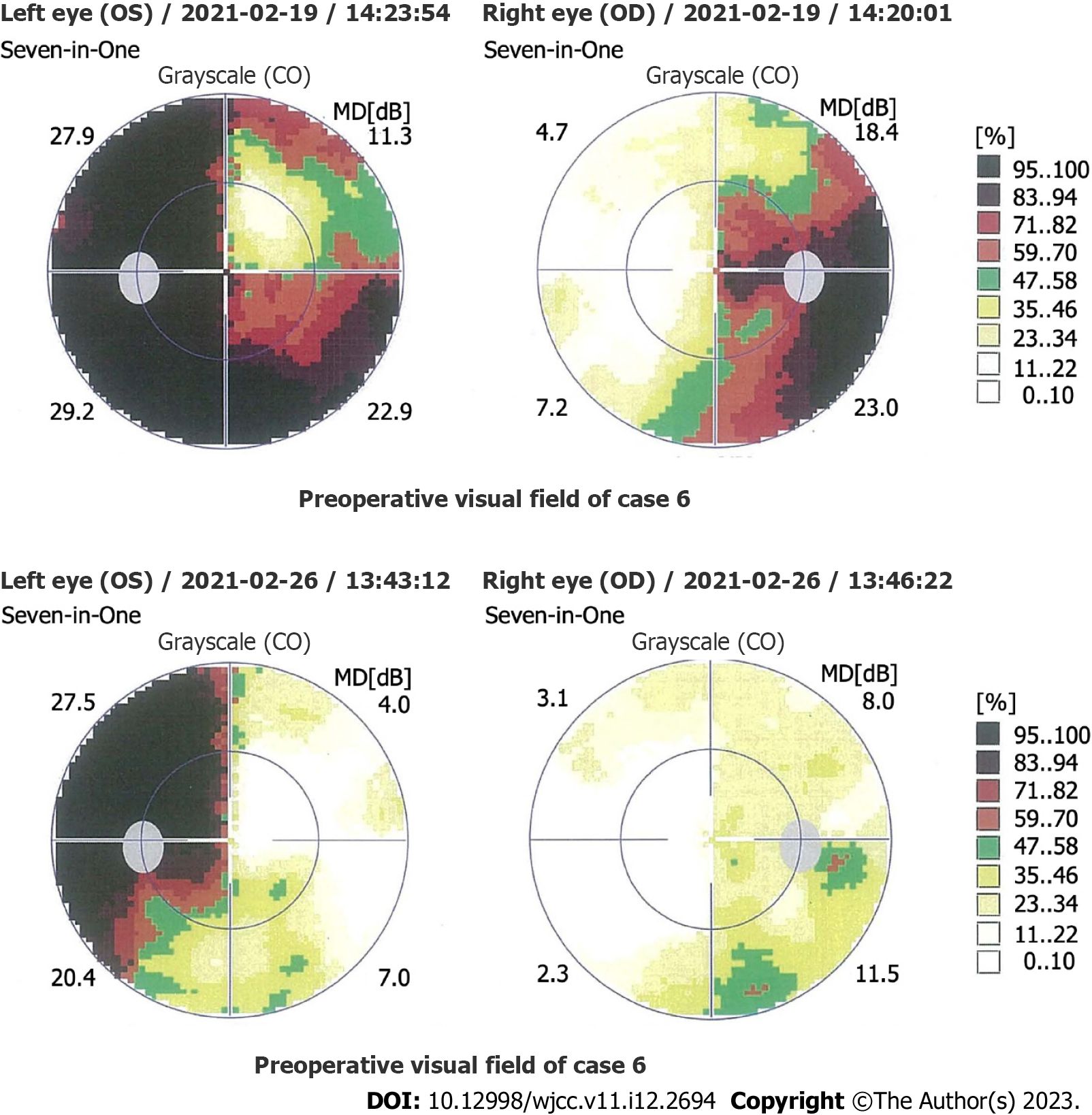

The clinical presentations of the 41 patients were as follows: visual field defects in 28 cases (68.3%) (bitemporal hemianopsia in 23 cases, unilateral temporal hemianopia in 5 cases; Figure 1); headaches in 27 cases (65.9%); vision loss in 20 cases (48.8%) (15 cases binocular, 5 cases monocular); Cushing syndrome in 7 cases (17.1%); acromegaly in 6 cases (14.6%); oculomotor paralysis in 4 cases (9.8%); diabetes insipidus in 2 cases (4.9%); and hyperthyroidism in 2 cases (4.9%).

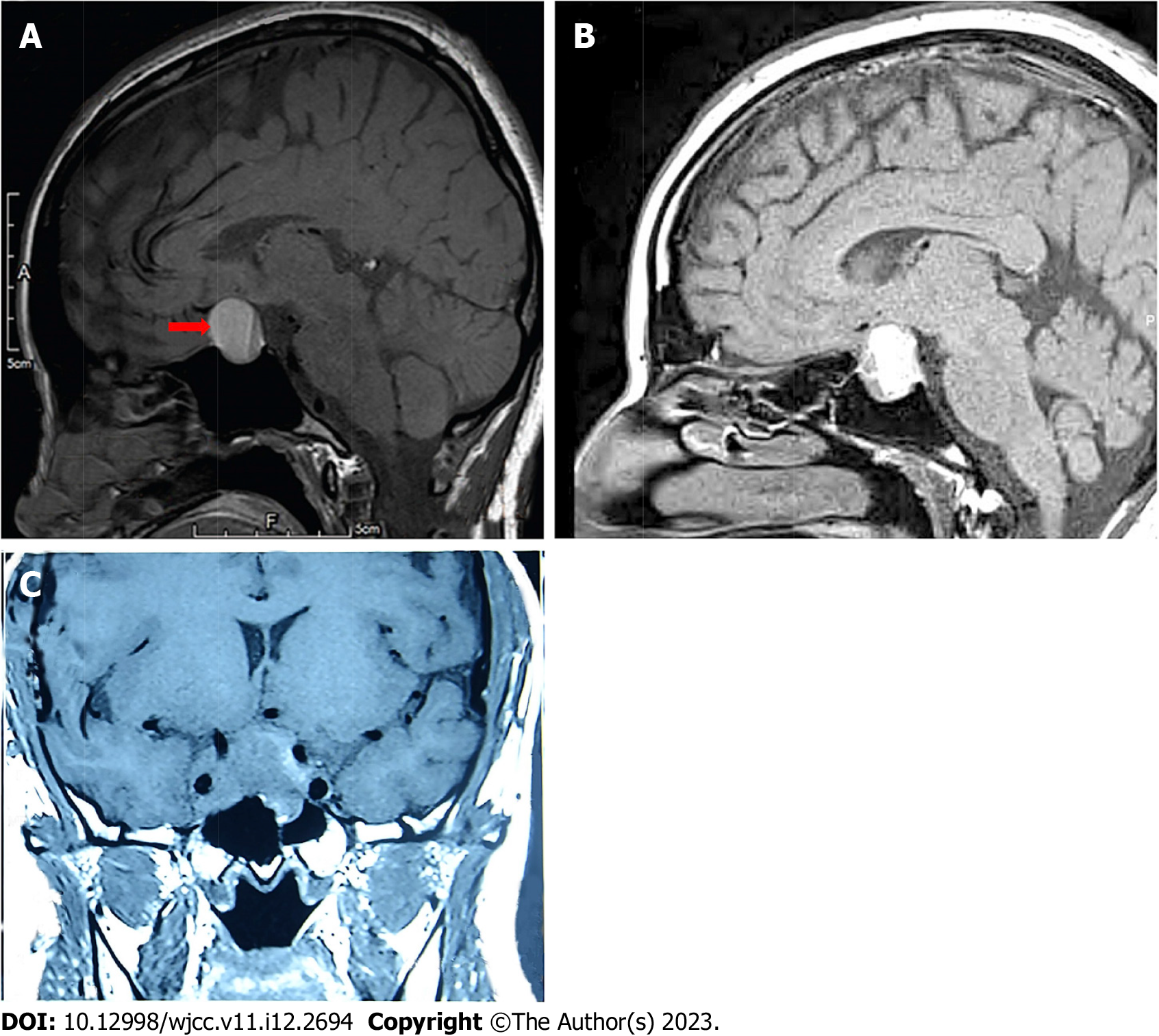

The imaging data of the 41 patients are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained for 37 of the patients (90.2%). Contrast-enhanced MRI was performed in 3 cases (7.3%), in which 1 case was obtained before pregnancy and 2 cases were obtained during pregnancy. Cranial enhanced computed tomography was performed in 1 case (2.4%) without MRI. The tumor sizes in the 27 patients with available data ranged from 0.4 cm to 4.0 cm (average: 2.1 ± 0.9 cm). Pituitary microadenomas were found in 2 patients. Up to 92.6% of patients (25 cases) had pituitary macro

Twenty-seven patients underwent T1 weighted imaging (T1WI), yielding hypointensity in 11.1% of cases (3/27), isointensity in 37.0% of cases (10/27), isointensity and hypointensity in 3.7% of cases (1/27), isointensity and hyperintensity in 29.6% of cases (8/27), and hyperintensity in 18.5% of cases (5/27). Three types of T1WI for cases with pituitary apoplexy were shown in Figure 2. None of the images showed hypointensity on T1WI.

Ten patients underwent T2 weighted imaging, yielding hypointensity in 10.0% of cases (1/10), hyperintensity in 40.0% of cases (4/10) and isointensity and hyperintensity in 50.0% of cases (5/10). Three of the four patients who underwent contrast-enhanced MRI showed no enhancement. The remaining case showed inhomogeneous enhancement.

The Knosp classification was reported in 20 patients. In 5 cases (25.0%), the classification was invasive (Knosp classification III or IV). In 15 cases (75.0%), the classification was non-invasive. Five patients were in the highest unilateral Knosp classification IV (25.0%). Two patients (10.0%) were in Knosp classification II. Nine patients (45.0%) were in Knosp classification I, and four patients (20.0%) were in Knosp classification 0.

Changes in hormone levels in the 41 patients were shown in Supplementary Table 2. Complete hormone monitoring was performed in 8 of 13 patients with prolactinoma. Prolactin levels decreased after operation, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

GH levels in 4 patients with complete hormone monitoring decreased postoperatively, although without statistical significance (P = 0.085). One patient (Case 11) had higher IGF1 on the 2nd day after surgery. However, the IGF1 level returned to normal after 6 mo. The IGF1 difference in the other 3 patients was not statistically significant (P = 0.115).

ACTH levels of the 3 patients completing hormone monitoring increased preoperatively and sharply decreased postoperatively. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). However, among 2 patients with decreased TSH levels postoperatively, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.308).

Perioperative conservative treatments for the 41 patients are shown in Table 2. Twenty-two patients did not receive conservative treatment. Among the remaining 19 patients, bromocriptine was used most frequently (57.9%, 11/19), including for 6 patients with prolactinoma, 3 patients with non-functioning PA, 1 patient with TSH-secreting PA, and 1 patient without pathological classification. The second most frequent preoperative drug group was glucocorticoids, including 5 patients with non-functioning PA, 1 patient with prolactinoma and 1 patient without pathological classification. Cabergoline, also a DA, ranked third with only 2 patients, including 1 patient with non-functioning PA and 1 patient with GH-secreting PA. Drugs also used for preoperative medication included sandostatin, thyroxine, propylthiouracil, alpha-methyldopa and 1-desamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin. Postoperatively, 30 patients received conservative treatment, comprising 13 cases of glucocorticoid treatment, 7 cases of thyroxine treatment, 5 cases of arginine-vasopressin treatment, and 5 cases of desmopressin treatment.

| Ref. | Case | Treatment | Pathology | Follow up | ||||

| Medical therapy | Operation | Delivery | M | I | ||||

| Pre | Post | |||||||

| Peking Union Medical College Hospital | 1 | Bromocriptine | No | 12th W TSS | 40th W CS | NF PA | ER | H |

| 2 | No | No | 32nd W TSS | Full term CS | NF PA | ER | H | |

| 3 | No | No | 22nd W TSS | 38th W CS | NF PA | ER | H | |

| 4 | Sandostatin | No | 26th W TSS | 38th W CS | TSH PA | ER | H | |

| 5 | Bromocriptine | No | 35th W TSS | 35th W CS | PRL PA | ER | H | |

| 6 | Prednisone, thyroxine | Prednisone, thyroxine | 30th W TSS | 39th W CS | NF PA | ER | H | |

| Jallad et al[16] | 7 | No | No | 3rd Mon TSS | 38thW CS | GH PA | ER | H |

| 8 | No | No | 4th Mon TSS | 16th W A | GH PA | EC | A | |

| 9 | Cabergoline | No | 4th Mon TSS | 39th W CS | GH PA | ER | H | |

| Chaiamnuay et al[17] | 10 | Propylthiouracil, bromocriptine | No | 27th W TSS | 39th W CS | TSH PA | ER | H |

| Guven et al[18] | 11 | No | Octreotide | 34th W TSS | 34th W CS | GH PA | EC | H |

| Zhong et al[38] | 12 | No | Cortisone, thyroxine | 22nd W TSS | 40th W VD | NF PA | ER | H |

| Jemel et al[19] | 13 | Cabergoline, hydrocortisone | No | 22nd W TSS | 37th W VD | NF PA | ER | H |

| 14 | Corticosteroids | No | 24th W TSS | 38th W VD | NF PA | ER | H | |

| Xia et al[20] | 15 | No | No | 24th W TSS | 38th W CS | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Yamaguchi et al[21] | 16 | No | Methyl prednisolone | 36th W TSS | 37th W CS | PRL PA, Optic neuritis | ER | H |

| Tandon et al[22] | 17 | Bromocriptine | Desmopressin | 36th W TSS | 37th W CS | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Parihar et al[36] | 18 | No | No | 20th W TSS | Full term VD | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Gondim et al[23] | 19 | Bromocriptine | Thyroxine, hydrocortisone | 32nd W TSS | 39th W VD | PRL PA | EC | H |

| Witek et al[24] | 20 | Bromocriptine | Hydrocortisone | 20th W TSS | 38th W CS | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Kita et al[25] | 21 | No | DDAVP | 27th W TSS | 40th W VD | NF PA | ER | H |

| Nossek et al[26] | 22 | No | No | 33rd W TSS | 35th W CS | PA | ER | LAS |

| 23 | No | No | 31st W TSS | 40th W VD | PA | ER | H | |

| Iuliano and Laws[27] | 24 | Bromocriptine, dexamethasone | No | 30th W TSS | 39th W CS | NF PA | ER | H |

| 25 | Bromocriptine, dexamethasone | Levothyroxine, hydrocortisone | 33rd W TSS | 39th W CS | NF PA | ER | H | |

| Hayes et al[28] | 26 | Corticosteroids | No | 18th W TSS | Full term VD | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Boronat et al[52] | 27 | Alpha-metildopa | Metyrapone | 16th W TSS | 34th W VD | ACTH PA | R | H |

| Abbassy et al[37] | 28 | No | Hydrocortisone, desmopressin | 18th W TSS | 39th W VD | ACTH PA | ER | H |

| Coyne et al[53] | 29 | No | Hydrocortisone, desmopressin | 14th W TSS | 38th W VD | ACTH PA | ER | H |

| Pinette et al[54] | 30 | No | Atenolol | 16th W TSS | - | ACTH PA | ER | D |

| Ross et al[55] | 31 | No | Dexamethasone | 18th W TSS | 37th W CS | ACTH PA | ER | H |

| Mellor et al[51] | 32 | No | Hydrocortisone | Mid-trimester TSS | 34th W CS | ACTH PA | ER | H |

| Karaca et al[15] | 33 | No | No | 11th W TSS | 39th W CS | GH PA | ER | H |

| Jolly et al[56] | 34 | No | Hydrocortisone, metformin, labetalol, nifedipine | 23rd W TSS | 38th W CS | ACTH PA | ER | D |

| Galvão et al[29] | 35 | No | No | 2nd trimester TSS | - | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Abid et al[30] | 36 | Bromocriptine | Lisuride hydrogen | 27th W TSS | 39th W VD | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Barraud et al[31] | 37 | Bromocriptine | No | 4th Mon TSS | - | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Freeman et al[32] | 38 | DDAVP | Hydrocortisone, thyroxine, DDAVP | 32nd W TSS | 39th W VD | PRL PA | ER | H |

| Lunardi et al[33] | 39 | No | No | 6th Mon TSS | Full term VD | GH PA | EC | H |

| Oguz et al[34] | 40 | No | Levothyroxine | 23rd W TSS | 37th W CS | PRL PA | ER | H |

| O’Neal[35] | 41 | Hydrocortisone, bromocriptine | No | 29th W TSS | 37th W VD | PA | ER | H |

All 41 patients underwent transsphenoidal surgery under general anesthesia. No patients were treated with craniotomy. With the exception of 7 patients who did not report their specific gestation, the surgical gestation of the other 34 patients ranged from 11 wk to 36 wk, with an average of 25.1 ± 7.1 wk. Two cases were in the first trimester (gestation < 14 wk; 5.9%), 19 cases in the second trimester (14 wk ≤ gestation < 28 wk; 55.9%, 19/34), and 13 cases in the third trimester (gestation ≥ 28 wk; 38.2%, 13/34).

Three cases (from PubMed) did not have pathologic classification reported. There were 13 cases (34.2%) of prolactinoma, 10 cases (26.3%) of non-functioning PA, 7 cases (18.4%) of ACTH-secreting PA, 6 cases (15.8%) of GH-secreting PA, and 2 cases (5.3%) of TSH-secreting PA.

Ten patients with non-functioning PA were not in remission, and twenty-six patients (63.4%) were in endocrine remission. Four patients (9.8%) were in endocrine control, and one patient (2.4%) relapsed. In terms of pregnancy outcomes, 1 patient underwent an induced abortion at 16 wk, and 1 fetus died due to a nuchal cord at 33 wk of gestation. The remaining 39 patients delivered 37 healthy fetuses successfully. One fetus died of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia within 36 h after caesarean section at 38 wk of gestation, and one fetus survived with a low Apgar score after caesarean section at 35 wk of gestation. Twenty-two patients underwent caesarean section (59.5%), and fifteen patients chose vaginal delivery (40.5%). The method of delivery was unknown for 2 patients.

Delivery gestation was not reported in 6 of the 39 patients. Of the remaining 33 patients, gestation ranged from 34 wk to 40 wk, averaging 37.8 ± 1.7 wk. Premature delivery (28 wk ≤ gestation < 37 wk) occurred in 5 cases (15.2%), and full-term delivery (37 wk ≤ gestation < 42 wk) occurred in 28 cases (84.8%).

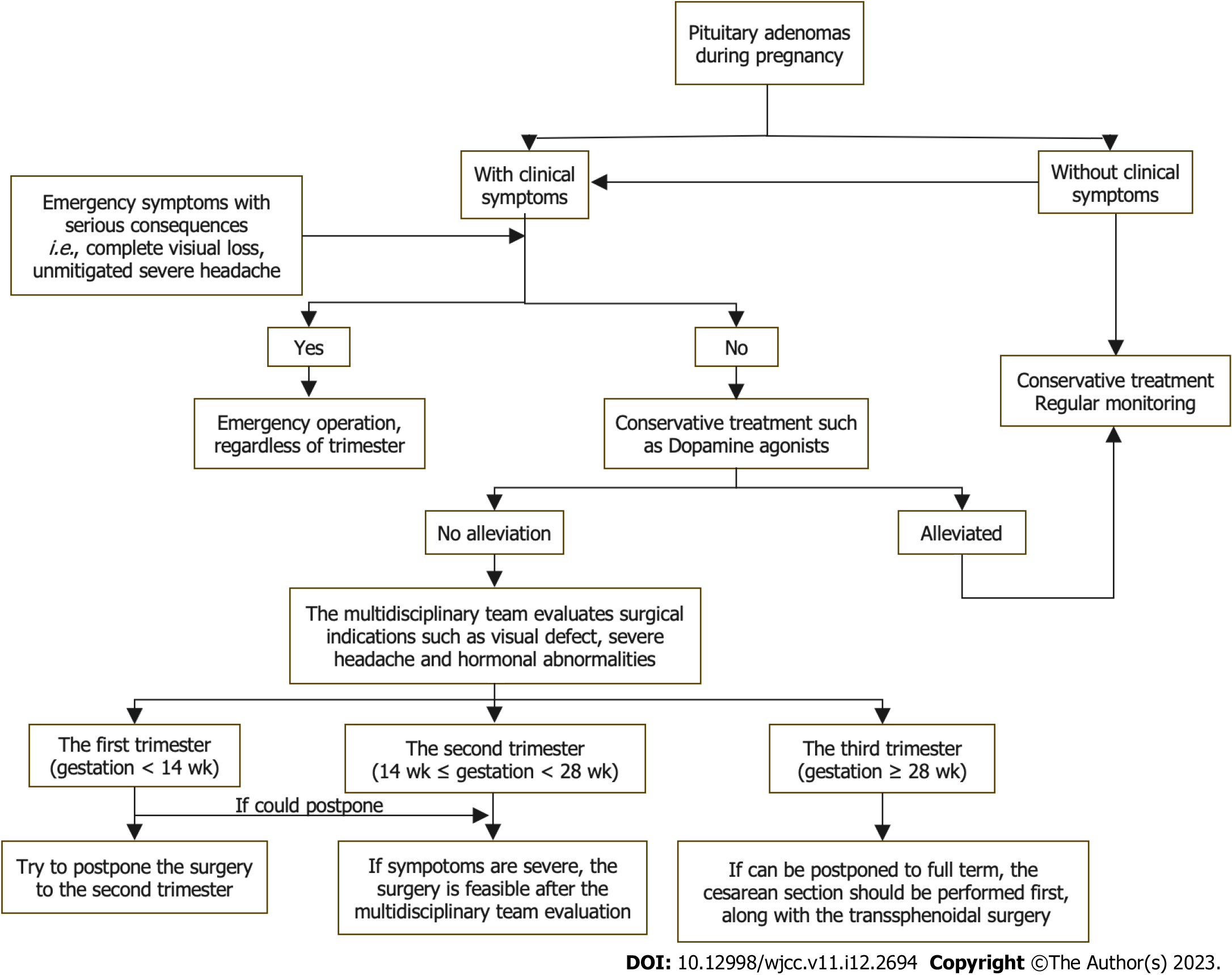

During pregnancy, physicians may face many challenges when diagnosing and treating PAs. Although conservative treatment is recommended for most pregnant patients with PAs, some patients must accept surgery due to visual defects, severe headaches and high hormone secretion levels that cannot be alleviated after conservative treatment[7,12-15]. We summarized the data of 41 patients with PAs who underwent surgery during pregnancy. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive report of surgical treatment of PAs in pregnant patients.

Here, the three most common clinical symptoms of these patients were visual field defects (68.3%), headaches (65.9%) and vision loss (48.8%). Previous studies showed that the two most common clinical symptoms of PA patients with apoplexy during pregnancy were headaches and visual impairment[19,34], which is similar to our study.

The pituitary gland and pre-existing PAs may enlarge during pregnancy[2,39], and the risk is greater in patients with macroadenomas than in those with microadenomas[1]. This observation was confirmed here. In prolactinomas, the most common type of PA, the risk of symptomatic tumor enlargement during pregnancy was 27.9% for patients with macroadenomas and only 2.2% for patients with microadenomas[40]. Although 2 patients in our study had pituitary microadenomas, their surgical indications were intractable diabetes insipidus and Cushing syndrome rather than symptomatic tumor enlargement[15,37].

Conservative treatment during pregnancy primarily includes DA treatment for prolactinomas[1] and SSA treatment for GH-secreting PAs[1,7]. Although there is no evidence that SSAs increase the risk of fetal malformation[6,41-43], discontinuation of all medication except DAs during pregnancy is recommended to ensure fetal health to the maximum extent possible[7,8,44]. Resuming other treatments is recommended only when symptoms leading to poor prognoses, such as visual defects or severe headaches, occur. When patients do not achieve significant remission after conservative treatment, clinicians should consider surgical treatment as soon as possible following a multidisciplinary evaluation[8,12,44]. Additionally, to ensure maternal health and fetal development, hormone deficiencies, such as glucocorticoid or thyroxine, should be treated[45].

Patients with macroadenomas have a higher risk of symptomatic progression during pregnancy[1]. However, the size of the PA is not the criterion. The severity of visual defects and headaches should be used as surgical indications for PA during pregnancy[12,13]. Some microadenomas are also associated with adverse effects on maternal and fetal health due to high hormone levels[46]. Based on our results, the surgical indications during pregnancy are summarized as follows.

Visual defects: PAs are more likely to compress the optic chiasm during pregnancy, leading to visual defects[2]. When conservative treatment cannot relieve visual impairment, clinicians should conduct a multidisciplinary evaluation to balance visual defects with pregnancy safety and decide whether to treat surgically as soon as possible. Although the recovery rate of the visual field can be as high as 80%[47] to 95.7%[48], the severity and duration of visual impairment are essential factors for postoperative visual prognosis. Irreversible adverse effects caused by severe visual impairment during pregnancy should be avoided[48].

Severe headache: Sudden, severe headache is the most common symptom of PA with apoplexy, primarily due to the enlargement of the PA during pregnancy, increased pressure on the sella turcica, and dural pressure[45]. Headache is often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, eye muscle paralysis and impairment of consciousness. Because severe headache can induce contractions, surgery is indicated if the multidisciplinary evaluation considers that the headache is due to mass effect and that pain medication would affect fetal health[49].

Hormonal abnormalities: Some PAs, such as ACTH-secreting PA and TSH-secreting PA, can cause ovulation disorders in women of reproductive age[50]. This type of patient should be treated before pregnancy as early as possible. Nevertheless, a few patients have unintended pregnancies after diagnosis[37,51,52] or are diagnosed during pregnancy[53-56]. High hormone secretion during pregnancy is closely related to several complications and poor prognoses[46,50]. Surgical treatment with appropriate timing is the most effective method for reducing hormone levels in such patients[12,17,44].

The timing of transsphenoidal surgery depends on the potential risks and benefits, including maternal symptoms, fetal safety and gestational weeks, which is the most critical indicator. The spontaneous abortion rate in the first trimester is approximately 12.0% vs 5.0% in the second and third trimesters[13]. The overall malformation incidence in pregnancy is 2.0% compared with 3.9% in the first trimester. The incidence of neural tube defects and preterm delivery is highest in the third trimester[57]. In our study, most patients also underwent surgery in the second trimester. Therefore, the second trimester is the best time for PA surgery[12-14,58,59].

For patients in the first trimester, the surgery should be postponed until the second trimester if possible[14,15]. For patients in the third trimester, Lynch et al[60] recommended delaying surgery to 30 wk of gestation if possible because fetal survival can reach 90% after 27 wk of gestation. In comparison, Priddy et al[14] suggested induction of labor or caesarean section at 34 wk of gestation followed by surgical treatment, if possible. However, among the 13 patients in this study who underwent surgeries in the third trimester, 12 patients and fetuses were healthy. One fetus survived with a low Apgar score, but the mother was healthy. In this regard, we suggest that the balance of symptom severity and gestational weeks should be considered in the third trimester when glucocorticoids can be administered to promote fetal lung maturation. If symptoms do not worsen significantly, a caesarean section should be performed first. However, surgical treatment should then be performed promptly if symptoms progress significantly (Figure 3).

Preoperative: A professional multidisciplinary team should be established to conduct individualized evaluations prior to surgery for pregnant patients with PAs indicated for surgical treatment. The team should include neurosurgeons, endocrinologists, obstetricians, gynecologists, pediatricians and anesthesiologists[20,59]. MRI must be acquired before the surgery. Although fetal toxicity of gadolinium is not established, MRI without gadolinium enhancement is preferred and is sufficient to make a definitive diagnosis and plan the surgery. Given the teratogenicity of X-rays, computed tomography should be avoided[61].

Preoperative ophthalmic examination is also essential, including examinations of visual acuity, visual field, fundus and retinal nerve fiber layer, and optical coherence tomography of the ganglion cell complex[12]. The ophthalmic examination can roughly predict the postoperative recovery rates for visual impairment[48]. The possible visual sequelae include severe visual impairment, severe visual field defects and severe degeneration of the retinal nerve fiber layer/ganglion cell complex[12].

Preoperative fetal ultrasonography should be performed routinely to evaluate fetal health. Continuous fetal heart rate monitoring is feasible under the proper conditions[12]. The endocrine examination can assess pituitary function. If necessary, relevant deficient hormones should be supplemented. Preoperative operations such as enemas that can induce contractions should be avoided. After evaluation, patients and their families should be fully informed of the risks and benefits of surgery. Written informed consent should be obtained after weighing the advantages and disadvantages.

Perioperative: Inhaled anesthetics can reduce uterine tension and increase bleeding risk and cerebral perfusion pressure in a concentration-dependent manner[62]. Total intravenous anesthesia, which is preferred during pregnancy, does not affect uterine tension and can constrict the cerebrovascular system and maintain cerebral perfusion pressure[63]. The United States Food and Drug Administration Class B drugs such as propofol are recommended. However, Class C drugs, which have potential risks but can be used given sufficient expected benefit, should be carefully used after considering the advantages and disadvantages[58].

Intraoperative reduction of cardiac return can lead to severe complications such as hypotension, placental insufficiency and cerebral insufficiency. Therefore, surgeons should lower the left side of the patient below the right side to avoid compression of the inferior vena cava[12,13]. Although there is no optimal cerebral perfusion pressure target, it seems reasonable to control the mean arterial pressure 20% above the baseline[13]. During surgery, the use of diuretics and anticonvulsants should be avoided. If necessary, contractions should be suppressed to protect the fetus[12].

Postoperative: Fetal heart rate variation is an essential indicator of fetal health and can indicate fetal distress. Therefore, continuous fetal heart rate monitoring should be performed after the surgery[13]. If postoperative reactions such as nausea, vomiting and headache occur, Class B drugs such as pethidine can be used for symptomatic treatment. Routine ophthalmic examinations should be conducted postoperatively to evaluate visual defect recovery. If no significant improvement is observed, differential diagnoses with other diseases leading to visual impairment, such as optic neuritis, should be considered[21]. Hormone stoss therapy, neurotrophic drugs and other treatments can also be administered.

Although this report is the largest case series of patients undergoing surgical treatment for pituitary tumors during pregnancy, limitations of this study include biases due to the retrospective study design and follow-up differences. In addition, although we have tried to include all cases, the number of cases is still relatively small. Therefore, we were unable to engage in analysis and discussion according to pathological classification. Prospective and multicenter studies with more cases are needed to further understand the surgical management of pituitary tumors during pregnancy.

The surgical treatment and perioperative management of PAs during pregnancy is complex. The surgical indications and timing issues must be well understood and carefully considered with the cooperation of neurosurgery, endocrinology, obstetrics, anesthesiology, neonatology and other related specialties. In the second and third trimesters, transsphenoidal surgery is a safe and effective approach for emergency treatment during pregnancy after evaluation by a multidisciplinary team. Additionally, for patients with irregular menstrual cycles, pituitary screening is necessary. Women of reproductive age who have been diagnosed with PAs should follow the advice of their endocrinologists and neurosurgeons before pregnancy.

Although conservative treatment is recommended for pregnant patients with pituitary adenomas (PAs), surgical treatment is occasionally necessary for those with acute symptoms.

Surgical intervention among pregnant patients with PAs has been poorly studied.

To evaluate the surgical indications, timing, complications and perioperative precautions of surgical treatment of PAs during pregnancy and to provide comprehensive guidance.

Six patients with PAs who underwent surgical treatment during pregnancy at Peking Union Medical College Hospital between January 1990 and June 2021 were included. Another 35 pregnant patients with PAs reported in the literature were also included. The surgical indications, timing of surgery, improvement of symptoms, postoperative complications and fetal condition were analyzed.

The 41 enrolled patients had acute symptoms including visual field defects, severe headaches or vision loss requiring emergency pituitary surgeries. PA apoplexies were found in 23 patients. The majority (55.9%) of patients underwent surgery in the second trimester of pregnancy. With the exception of 1 patient who underwent an induced abortion and 1 fetus who died due to a nuchal cord, 39 patients delivered successfully, and 37 of the fetuses were healthy at the most recent follow-up.

PA surgery during pregnancy is effective and safe during the second and third trimesters. Pregnant patients requiring emergency PA surgery require multidisciplinary evaluation and healthcare management.

Multicenter, large sample, randomized controlled clinical trials are still needed to improve the standardized guidelines for the surgical treatment of pituitary tumors during pregnancy.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: China Pituitary Adenoma Specialist Council.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tolunay HE, Turkey S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Woodmansee WW. Pituitary Disorders in Pregnancy. Neurol Clin. 2019;37:63-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dinç H, Esen F, Demirci A, Sari A, Resit Gümele H. Pituitary dimensions and volume measurements in pregnancy and post partum. MR assessment. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Karaca Z, Tanriverdi F, Unluhizarci K, Kelestimur F. Pregnancy and pituitary disorders. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:453-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Casanueva FF, Molitch ME, Schlechte JA, Abs R, Bonert V, Bronstein MD, Brue T, Cappabianca P, Colao A, Fahlbusch R, Fideleff H, Hadani M, Kelly P, Kleinberg D, Laws E, Marek J, Scanlon M, Sobrinho LG, Wass JA, Giustina A. Guidelines of the Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;65:265-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Grand'Maison S, Weber F, Bédard MJ, Mahone M, Godbout A. Pituitary apoplexy in pregnancy: A case series and literature review. Obstet Med. 2015;8:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Molitch ME. Endocrinology in pregnancy: management of the pregnant patient with a prolactinoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172:R205-R213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Laway BA. Pregnancy in acromegaly. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2015;6:267-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Muhammad A, Neggers SJ, van der Lely AJ. Pregnancy and acromegaly. Pituitary. 2017;20:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guo X, Guo Y, Xing B, Ma W. The Initial Stage of Neurosurgery in China: Contributions from Peking Union Medical College Hospital. World Neurosurg. 2021;149:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wilson JD. Peking Union Medical College Hospital, a palace of endocrine treasures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:815-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sant' Anna BG, Musolino NRC, Gadelha MR, Marques C, Castro M, Elias PCL, Vilar L, Lyra R, Martins MRA, Quidute ARP, Abucham J, Nazato D, Garmes HM, Fontana MLC, Boguszewski CL, Bueno CB, Czepielewski MA, Portes ES, Nunes-Nogueira VS, Ribeiro-Oliveira A Jr, Francisco RPV, Bronstein MD, Glezer A. A Brazilian multicentre study evaluating pregnancies induced by cabergoline in patients harboring prolactinomas. Pituitary. 2020;23:120-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Graillon T, Cuny T, Castinetti F, Courbière B, Cousin M, Albarel F, Morange I, Bruder N, Brue T, Dufour H. Surgical indications for pituitary tumors during pregnancy: a literature review. Pituitary. 2020;23:189-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chowdhury T, Chowdhury M, Schaller B, Cappellani RB, Daya J. Perioperative considerations for neurosurgical procedures in the gravid patient: Continuing Professional Development. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:1139-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Priddy BH, Otto BA, Carrau RL, Prevedello DM. Management of Skull Base Tumors in the Obstetric Population: A Case Series. World Neurosurg. 2018;113:e373-e382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Karaca Z, Yarman S, Ozbas I, Kadioglu P, Akturk M, Kilicli F, Dokmetas HS, Colak R, Atmaca H, Canturk Z, Altuntas Y, Ozbey N, Hatipoglu N, Tanriverdi F, Unluhizarci K, Kelestimur F. How does pregnancy affect the patients with pituitary adenomas: a study on 113 pregnancies from Turkey. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41:129-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jallad RS, Shimon I, Fraenkel M, Medvedovsky V, Akirov A, Duarte FH, Bronstein MD. Outcome of pregnancies in a large cohort of women with acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018;88:896-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chaiamnuay S, Moster M, Katz MR, Kim YN. Successful management of a pregnant woman with a TSH secreting pituitary adenoma with surgical and medical therapy. Pituitary. 2003;6:109-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guven S, Durukan T, Berker M, Basaran A, Saygan-Karamursel B, Palaoglu S. A case of acromegaly in pregnancy: concomitant transsphenoidal adenomectomy and cesarean section. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:69-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jemel M, Kandara H, Riahi M, Gharbi R, Nagi S, Kamoun I. Gestational pituitary apoplexy: Case series and review of the literature. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48:873-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xia Y, Ma X, Griffiths BB, Luo Y. Neurosurgical anesthesia for a pregnant woman with macroprolactinoma: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yamaguchi R, Kohga H, Tosaka M, Sekine A, Mizushima K, Harigaya Y, Yoshimoto Y. A Case of Optic Neuritis Concomitant with Pituitary Tumor During Pregnancy. World Neurosurg. 2016;93:488.e1-488.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tandon A, Alzate J, LaSala P, Fried MP. Endoscopic Endonasal Transsphenoidal Resection for Pituitary Apoplexy during the Third Trimester of Pregnancy. Surg Res Pract. 2014;2014:397131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gondim J, Ramos Júnior F, Pinheiro I, Schops M, Tella Júnior OI. Minimally invasive pituitary surgery in a hemorrhagic necrosis of adenoma during pregnancy. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2003;46:173-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Witek P, Zieliński G, Maksymowicz M, Zgliczyński W. Transsphenoidal surgery for a life-threatening prolactinoma apoplexy during pregnancy. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2012;33:483-488. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kita D, Hayashi Y, Sano H, Takamura T, Tachibana O, Hamada J. Postoperative diabetes insipidus associated with pituitary apoplexy during pregnancy. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2012;33:107-112. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Nossek E, Ekstein M, Rimon E, Kupferminc MJ, Ram Z. Neurosurgery and pregnancy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2011;153:1727-1735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Iuliano S, Laws ER Jr. Management of pituitary tumors in pregnancy. Semin Neurol. 2011;31:423-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hayes AR, O'Sullivan AJ, Davies MA. A case of pituitary apoplexy in pregnancy. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2014;2014:140043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Galvão A, Gonçalves D, Moreira M, Inocêncio G, Silva C, Braga J. Prolactinoma and pregnancy - a series of cases including pituitary apoplexy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37:284-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Abid S, Sadiq I, Anwar S, Hafeez M, Butt F. Pregnancy with macroprolactinoma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:787-788. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Barraud S, Guédra L, Delemer B, Raverot G, Ancelle D, Fèvre A, Jouanneau E, Litré CF, Wolak-Thierry A, Borson-Chazot F, Decoudier B. Evolution of macroprolactinomas during pregnancy: A cohort study of 85 pregnancies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2020;92:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Freeman R, Wezenter B, Silverstein M, Kuo D, Weiss KL, Kantrowitz AB, Schubart UK. Pregnancy-associated subacute hemorrhage into a prolactinoma resulting in diabetes insipidus. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:427-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lunardi P, Rizzo A, Missori P, Fraioli B. Pituitary apoplexy in an acromegalic woman operated on during pregnancy by transphenoidal approach. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1991;34:71-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Oguz SH, Soylemezoglu F, Dagdelen S, Erbas T. A case of atypical macroprolactinoma presenting with pituitary apoplexy during pregnancy and review of the literature. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;36:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | O'Neal MA. Headaches complicating pregnancy and the postpartum period. Pract Neurol. 2017;17:191-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Parihar V, Yadav YR, Sharma D. Pituitary apoplexy in a pregnant woman. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2009;12:54-55. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Abbassy M, Kshettry VR, Hamrahian AH, Johnston PC, Dobri GA, Avitsian R, Woodard TD, Recinos PF. Surgical management of recurrent Cushing's disease in pregnancy: A case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:S640-S645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhong HP, Tang H, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Yao H, Cheng Y, Gu WT, Wei YX, Wu ZB. Multidisciplinary team efforts improve the surgical outcomes of sellar region lesions during pregnancy. Endocrine. 2019;66:477-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Inoue T, Hotta A, Awai M, Tanihara H. Loss of vision due to a physiologic pituitary enlargement during normal pregnancy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:1049-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Molitch ME. Prolactinomas and pregnancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;73:147-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lebbe M, Hubinont C, Bernard P, Maiter D. Outcome of 100 pregnancies initiated under treatment with cabergoline in hyperprolactinaemic women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;73:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Stalldecker G, Mallea-Gil MS, Guitelman M, Alfieri A, Ballarino MC, Boero L, Chervin A, Danilowicz K, Diez S, Fainstein-Day P, García-Basavilbaso N, Glerean M, Gollan V, Katz D, Loto MG, Manavela M, Rogozinski AS, Servidio M, Vitale NM. Effects of cabergoline on pregnancy and embryo-fetal development: retrospective study on 103 pregnancies and a review of the literature. Pituitary. 2010;13:345-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Caron P, Broussaud S, Bertherat J, Borson-Chazot F, Brue T, Cortet-Rudelli C, Chanson P. Acromegaly and pregnancy: a retrospective multicenter study of 59 pregnancies in 46 women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4680-4687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Bronstein MD, Paraiba DB, Jallad RS. Management of pituitary tumors in pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:301-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Piantanida E, Gallo D, Lombardi V, Tanda ML, Lai A, Ghezzi F, Minotto R, Tabano A, Cerati M, Azzolini C, Balbi S, Baruzzi F, Sessa F, Bartalena L. Pituitary apoplexy during pregnancy: a rare, but dangerous headache. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;37:789-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Bronstein MD, Machado MC, Fragoso MC. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Management of pregnant patients with Cushing's syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173:R85-R91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Muskens IS, Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, Briceno V, Lamba N, Senders JT, van Furth WR, Verstegen MJT, Smith TRS, Mekary RA, Eenhorst CAE, Broekman MLD. Visual outcomes after endoscopic endonasal pituitary adenoma resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pituitary. 2017;20:539-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Barzaghi LR, Medone M, Losa M, Bianchi S, Giovanelli M, Mortini P. Prognostic factors of visual field improvement after trans-sphenoidal approach for pituitary macroadenomas: review of the literature and analysis by quantitative method. Neurosurg Rev. 2012;35:369-78; discussion 378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Negro A, Delaruelle Z, Ivanova TA, Khan S, Ornello R, Raffaelli B, Terrin A, Reuter U, Mitsikostas DD; European Headache Federation School of Advanced Studies (EHF-SAS). Headache and pregnancy: a systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kyriakos G, Farmaki P, Voutyritsa E, Patsouras A, Quiles-Sánchez LV, Damaskos C, Stelianidi A, Pastor-Alcaraz A, Palomero-Entrenas P, Diamantis E. Cushing's syndrome in pregnancy: a review of reported cases. Endokrynol Pol. 2021;72:64-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Mellor A, Harvey RD, Pobereskin LH, Sneyd JR. Cushing's disease treated by trans-sphenoidal selective adenomectomy in mid-pregnancy. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:850-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Boronat M, Marrero D, López-Plasencia Y, Barber M, Schamann Y, Nóvoa FJ. Successful outcome of pregnancy in a patient with Cushing's disease under treatment with ketoconazole during the first trimester of gestation. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27:675-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Coyne TJ, Atkinson RL, Prins JB. Adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting pituitary tumor associated with pregnancy: case report. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:953-5; discussion 955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Pinette MG, Pan YQ, Oppenheim D, Pinette SG, Blackstone J. Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus corticotropin sampling with corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulation in a pregnant patient with Cushing's syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:563-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ross RJ, Chew SL, Perry L, Erskine K, Medbak S, Afshar F. Diagnosis and selective cure of Cushing's disease during pregnancy by transsphenoidal surgery. Eur J Endocrinol. 1995;132:722-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Jolly K, Darr A, Arlt W, Ahmed S, Karavitaki N. Surgery for Cushing's disease in pregnancy: our experience and a literature review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101:e26-e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Mazze RI, Källén B. Reproductive outcome after anesthesia and operation during pregnancy: a registry study of 5405 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1178-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Marulasiddappa V, Raghavendra B, Nethra H. Anaesthetic management of a pregnant patient with intracranial space occupying lesion for craniotomy. Indian J Anaesth. 2014;58:739-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Cohen-Gadol AA, Friedman JA, Friedman JD, Tubbs RS, Munis JR, Meyer FB. Neurosurgical management of intracranial lesions in the pregnant patient: a 36-year institutional experience and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:1150-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Lynch JC, Gouvêa F, Emmerich JC, Kokinovrachos G, Pereira C, Welling L, Kislanov S. Management strategy for brain tumour diagnosed during pregnancy. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:225-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Jain C. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 723: Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Yoo KY, Lee JC, Yoon MH, Shin MH, Kim SJ, Kim YH, Song TB, Lee J. The effects of volatile anesthetics on spontaneous contractility of isolated human pregnant uterine muscle: a comparison among sevoflurane, desflurane, isoflurane, and halothane. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:443-447, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Cole CD, Gottfried ON, Gupta DK, Couldwell WT. Total intravenous anesthesia: advantages for intracranial surgery. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:369-77; discussion 377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |