Published online Apr 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i12.2631

Peer-review started: November 19, 2022

First decision: December 10, 2022

Revised: February 10, 2023

Accepted: March 27, 2023

Article in press: March 27, 2023

Published online: April 26, 2023

Processing time: 157 Days and 11.2 Hours

Pancreatic cancer is a highly devastating disease with high mortality rates. Even patients who undergo potential curative surgery have a high risk for recurrence. The incidence of depression and anxiety are higher in patients with cancer than the general population. However, patients with pancreatic cancer are at most of risk of both depression and anxiety and there seems to be a biological link. In some patients, depression seems to be a precursor to pancreatic cancer. In this article we discuss the biological link between depression anxiety and hepatobiliary malignancies and discuss treatment strategies.

Core Tip: Pancreatic cancer has one of the highest mortality rates of all malignancies. There is a strong correlation between pancreatic cancer and depression and we discuss the evidence behind this.

- Citation: Michoglou K, Ravinthiranathan A, San Ti S, Dolly S, Thillai K. Pancreatic cancer and depression. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(12): 2631-2636

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i12/2631.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i12.2631

Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death, with very poor 5-year survival rates[1]. The majority of patients present at a late stage with incurable disease. Initial symptoms can be vague and are often wrongly attributed to more common diagnoses. It is usually only when an individual develops visible changes (i.e. jaundice as a result of bile duct blockage) that they receive medical attention, by which time, the cancer tends to be more advanced. The significant morbidity and mortality of the disease could explain why pancreatic cancer has the highest incidence rates of depression compared with other types of gastrointestinal cancers[2]. There is a known correlation between malignancies and depression[3]; however it is unclear as to whether the depression is a result of the challenges of the cancer itself, reactive to the diagnosis or related to physiological changes from the cancer. Some studies have suggested depression before a cancer diagnosis is actually a sign of the malignant process at work; implying that it is individual symptom of the cancer[2]. The link between pancreatic cancer and depression was identified nearly a century ago. Retrospectives from the 1930’s; identified as associated with pancreatic cancer and three psychological symptoms: Depression, anxiety; and sense of impending doom[4]. It appeared that these symptoms had preceded the somatic clinical symptoms of pancreatic cancer (i.e., pain; jaundice; weight loss). This article will review the suggested biological link between depression, anxiety and pancreatic cancer, with the aim to identify potential biomarkers, which could be implemented in a more individualized and targeted approach in pancreatic cancer treatments.

Yet rather than a reactive effect of being given a life changing prognosis, research has shown that depression can be the presenting symptom of pancreatic cancer, with the subsequent development of anorexia, weight loss, jaundice, and pain[4]. It is well reported that pancreatic cancer has the highest incidence rate of depression among all other tumours of the digestive system[5]. It is also known that psychological symptoms are quite common in the course of visceral disease, most noticed in advanced stages of gastro-intestinal diseases and other chronic diseases. Previous research studies have reported that abdominal pain is more likely to cause depression, than pain in any other region. One of the first studies by Yaskin et al[4], dated back in 1931, focused on four case reports with “nervous symptoms”, predominantly anxiety, followed by anorexia, weight loss and weakness. In all four cases, the nervous symptoms significantly preceded any of the definite gastro-intestinal symptoms and signs by several months. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma was later confirmed in three of the four cases, and in the fourth case this was the most probable diagnosis. In 1970s, a retrospective study of patients with known gastric and pancreatic cancer, revealed that depression was already present at the time of the diagnosis of cancer, in 14% of patients with pancreatic cancer, as opposed to 4% of patients with gastric cancer[6]. Further research conducted by Mayo Clinic, attempted to assess patients with abdominal symptoms, following surgical resection, and it was found that 76% of patients with confirmed pancreatic cancer had symptoms of depression and anxiety, compared to 20% of patients with other neoplasms[2]. Interestingly, in half of the patients the psychiatric symptoms started as early as 43 mo before the somatic symptoms. This was an important research mark, as psychiatric symptoms could be used as a key to make an earlier diagnosis of pancreatic cancer[7]. A systematic psychiatric evaluation of 21 patients with intraabdominal malignancy (pancreatic or gastric carcinoma) also revealed that depression was more frequently associated with patients with pancreatic carcinoma, whereby this finding was not observed in patients with gastric cancer[8]. A further study of 107 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and 111 patients with advanced gastric cancer, were assessed with the’ Profile of Mood States’ before beginning combination chemotherapy in a national cancer clinical trials group[9]. The pancreatic cancer patients had more severe depression, anxiety, fatigue, and mood disturbances. These data support prior observations that patients with advanced pancreatic cancer experience significantly greater general psychological disturbances compared to patients with other abdominal malignancies in advanced stage[9]. A comprehensive meta-analysis by Massie et al[10] revealed that the prevalence of depression in pancreatic cancer ranges from 33% to 50%, based on a small number of studies, and including 229 patients in total[7-10]. A large retrospective study by Zabora et al[11], examined 4496 patients with 14 different cancer diagnoses, and found that patients with pancreatic cancer had the highest mean score for depression and anxiety. 36.6% of patients with pancreatic cancer had distress as evaluated by the Brief Symptom Inventory.

One of the largest studies conducted in United States, evaluated the rates of depression before and after a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, which were the highest in pancreatic cancer compared to other types of cancer, and demonstrating a peak within 6 mo before or after a pancreatic cancer diagnosis[12]. This study demonstrated that 21% of pancreatic cancer patients had depression prior to the cancer diagnosis. This supported the hypothesis that depression is potential antecedent to pancreatic cancer and therefore could be an early sign of pancreatic cancer. Recent prospective observational studies have assessed the prevalence of preoperative fatigue, depression and anxiety among patients undergoing pancreatic surgery for pancreatic cancer, and the possible link with postoperative outcomes. These studies have supported that patients with metastatic disease who experienced depression or anxiety before the pancreatic cancer diagnosis, were associated with a reduced likelihood of receiving chemotherapy, and decrease in overall survival[13]. This can be considered as a benchmark in future design of prospective clinical trials, which could suggest new treatment strategies, including antidepressant pharmacological agents, by implementing pre-existing depression as a stratification factor. The challenge remains on whether these new treatment strategies could be translated into survival benefit in this group of patients.

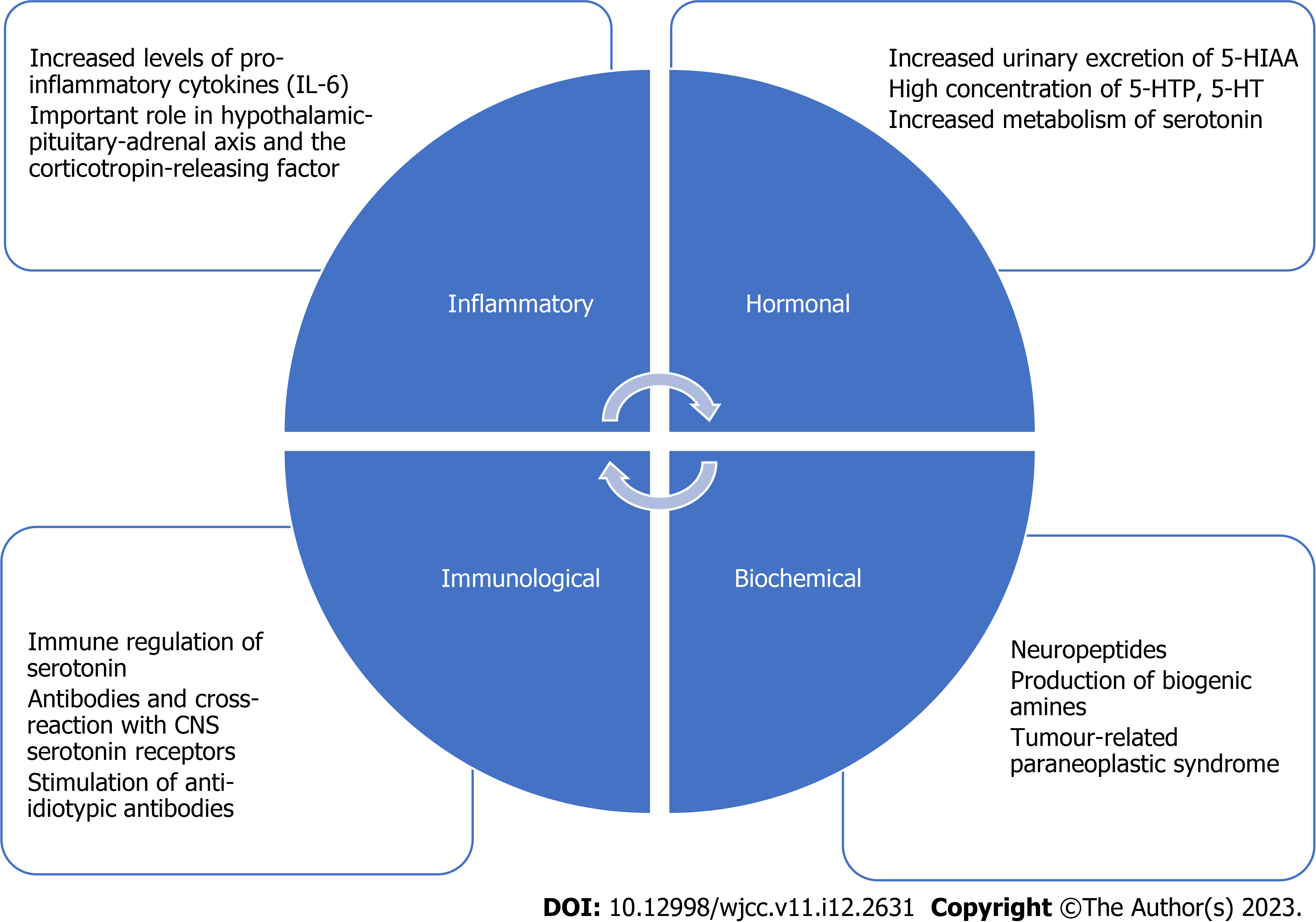

One of the most challenging features of this disease is the paucity of clear biomarkers compared with other solid malignancies. Whilst several have been proposed, there remains no gold standard that has been validated for use. By understanding what biological drivers cause depression as an initial symptom, a biomarker may be used to identify underlying pancreatic malignancy. It is widely known that gastrointestinal malignancies are commonly causes for psychological and mental health conditions. This could be explained by the mechanical pressure of the tumour and interference by its toxic effects and metabolic changes. Chemical changes in the body have a causative relation to abnormal emotional states, with common examples being depression of hyperthyroidism and the anxiety and restlessness of abnormal blood sugars[4]. Several studies have attempted to prove a relationship between depression and cytokine production[14]. Increased levels of cytokines in the hypothalamus play a vital role in the cachexia-anorexia syndrome in cancer. Moreover, the increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1beta, TNF-alpha, Il-6, IL-18 is noticed in malignancy, and they may have impact on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the corticotropin-releasing factor[15]. The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 has been found to be significantly increased in pancreatic cancer cells, and is related to proliferation of tumour cells and reduced apoptosis, further suggesting a potential resistance to systemic treatments[16]. A study with 75 patients, conducted by two centres in New York, enrolled patients with pancreatic cancer with or without major depressive episode. Pancreatic cancer patients had significantly higher levels of IL-6 and IL-10 compared to healthy participants. This study demonstrated an association between depression and IL-6, but not with other cytokines. IL-6 had the strongest association with pancreatic cancer[14]. TNF-alpha was not associated with pancreatic cancer or any psychological distress. Another comprehensive study, published in 2008, assessed the clinical significance of -174G/C IL-6 gene polymorphism and IL-6 serum levels, which were significantly raised in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and in patients with chronic pancreatitis, compared to the control group[17]. Hormonal theories support that pancreatic cancer patients might have increased urinary excretion of 5-hydroxyindolaceetic acid (5-HIAA), which is a metabolite of serotonin, and high concentration of 5-hydroxytryptophne (5-HTP) or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT). This hypothesis suggests there is a likely correlation between increased metabolism of serotonin in pancreatic cancer, which leads to central nervous system depletion and therefore depression[18]. Serotonin is produced by normal pancreatic cells and plays a role in the pathogenesis of depression[19]. This theory was further supported by suggested study demonstrating an increase in 5-HIAA is a link to depression and explained by the fact that there was treatment-refractory depression, until the tumour was excised[8]. Thyroid hormone abnormalities, hypercalcaemia, inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion and increased levels of adrenocorticotrophic hormone have also been documented in pancreatic cancer[19].

An immunological model was proposed by Brown and Paraskevas, whereby immune regulation of serotonin could be modulated in one of two ways. An antibody could be produced in response to a protein released by cancer cells that would cross-react with CNS serotonin receptors, thereby effectively blocking them. Alternatively, antibodies could stimulate the production of anti-idiotypic antibodies, which would reduce the synaptic availability of serotonin by acting as an alternate receptor. Depression contributes to impairment of immune competence or to development or progression of pancreatic cancer[20]. Furthermore, biochemical mechanisms support that tumours of the gastro-intestinal tract, which are rich in neuropeptides, may lead to production of biogenic amines that alter the psychological state. Some studies support the possibility of a tumour-related paraneoplastic syndrome, which promotes the production of a false neurotransmitter capable of altering mood[9]. These theories, which are summarized in Figure 1, have led to a better understanding of the biological association between pancreatic cancer and depressive symptoms, but further research is needed to validate new pathways of prevention, screening, and treatments.

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the immune landscape of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, genetic alterations and tumour microenvironment. A number of genetic alterations have been identified in pancreatic cancer, with KRAS mutations found in the majority of pancreatic cancer patients. Other signalling pathways found to be associated with pancreatic cancer, include alterations in tumour suppression genes (TP53, SMAD4, p16) and overexpression of growth factor receptors. The direct targeting of the involved signalling molecules and the immune checkpoint molecules, along with a combination with conventional therapies, have reached the most promising results in pancreatic cancer treatment[21]. Several novel targeted agents have failed to demonstrate an improvement in response rates and overall survival. PAK4, a serine threonine kinase, has been found to be overexpressed in pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients, and is known to mediate cell proliferation. PAK4, has been identified as a potential target in several tumours and its prominence in pancreatic cancer suggests it could present a therapeutic opportunity[22].

Early identification and treatment is essential in the management of patients with pancreatic cancer. Psychiatric symptoms cannot be accurately assessed in the presence of uncontrolled pain; therefore, the first step is to ameliorate the pain, agitation, and insomnia. The pharmacologic therapy includes antidepressant drugs, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, psychostimulants, or benzodiazepines. The choice of the antidepressant agent should be determined according to patient’s comorbidities and performance status, main target symptoms, potential interactions with co-administered drugs, and toxicity profile[23]. Tricyclic antidepressants have been reported as the most used drugs for depression in pancreatic cancer patients[24]. These drugs are usually initiated at low doses and then are slowly increased until adequate response is achieved. Amitriptyline has both antidepressant and analgesic action. The psychostimulants are helpful in pancreatic cancer because they stimulate appetite and improve energy[18]. Due to increased serotonin levels in pancreatic cancer, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors can be effective and are the preferred first line treatment according to NICE recommendations for depression in adults with a chronic physical health condition[25,26]. Benzodiazepines are more effective to patients with prevalent symptoms of anxiety but may increase psychomotor slowing and fatigue which is a very general complaint of cancer patients. Essential component of the first line treatment of major depression, is supportive psychotherapy. The integration of a mental health professional into the treatment plan of pancreatic cancer significantly decreased all-cause mortality rates compared to patients who were not treated by a mental health professional[12]. This was also supported by Boyd et al[27], demonstrating that integrating mental health specialists into patient care once depressive symptoms have been identified could enhance quality of life. However, this therapy is unlikely to significantly improve overall survival. Patients with pancreatic cancer often have unmet psychological support needs, that have a significant impact on their quality of life. Psychological support is crucial from time of cancer diagnosis and highlights the need to assess the psychological impact of fatigue, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, nutrition, anxiety, and depression[28]. It is also important for patients and their family members to be taught coping strategies. Beyond pharmacological agents and cognitive behavioural therapy, the management of cancer patients as a whole, is essential. Pain control, nutritional support and management of biliary and duodenal obstruction are essential in improving quality of life.

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the most challenging malignancies to manage, having very poor prognosis with low 5-year survival rates. It is also the malignancy with the highest incidence rates of major depression[2]. Research has shown that there are clear biological mechanisms linking depression with pancreatic cancer, but further research is urgently needed to unravel this link further and identify potential biomarkers, that could lead to early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and implement new treatment strategies. The current field lacks biomarker-driven targeted therapy. Furthermore, genomic stratification factors should be implemented in future clinical trials, as selected patients could be chosen based on genetic alterations in order to achieve maximal benefit from treatment and improve survival outcomes[21]. One of the main limitations remains the design of innovating clinical trials and the need of including psychological symptoms and depression as stratification factors. Prospective analyses could demonstrate whether depression and psychological factors have an impact on survival outcomes. It is also fundamental that future research follows a more holistic approach, highlighting the importance of multidisciplinary team support, and early involvement of mental health professionals. Undoubtedly, there are challenges in managing depression and anxiety in the context of malignancy and care must be multi-professional. Whilst depression, although common among patients with pancreatic cancer, does not routinely affect survival, it has significant effects on quality of life and potential adherence to treatment and engagement with care that could negatively impact outcomes[29]. However, early detection of psychological symptoms and involvement of mental health professionals, in combination with appropriate pharmacological agents, can lead to better outcomes and improve quality of life. There is a high unmet need for further improvement in the primary health care services and application of screening tools for early detection of depression and anxiety could be introduced in Rapid Access Diagnostic Clinics, as depression itself could be considered as a precursor to pancreatic cancer.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Solimando AG, Italy; Zhao CF, China S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Hu JX, Zhao CF, Chen WB, Liu QC, Li QW, Lin YY, Gao F. Pancreatic cancer: A review of epidemiology, trend, and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:4298-4321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 2. | Fras I, Litin EM, Bartholomew LG. Mental symptoms as an aid in the early diagnosis of carcinoma of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:191-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Hinz A, Krauss O, Hauss JP, Höckel M, Kortmann RD, Stolzenburg JU, Schwarz R. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients compared with the general population. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19:522-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yaskin JC. Nervous symptoms as earliest manifestations of carcinoma of the pancreas. JAMA. 1931;96:1664-1668. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Clark KL, Loscalzo M, Trask PC, Zabora J, Philip EJ. Psychological distress in patients with pancreatic cancer--an understudied group. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1313-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jacobsson L, Ottosson JO. Initial mental disorders in carcinoma of pancreas and stomach. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1971;221:120-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fras I, Litin EM, Pearson JS. Comparison of psychiatric symptoms in carcinoma of the pancreas with those in some other intra-abdominal neoplasms. Am J Psychiatry. 1967;123:1553-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Joffe RT, Rubinow DR, Denicoff KD, Maher M, Sindelar WF. Depression and carcinoma of the pancreas. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1986;8:241-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Holland JC, Korzun AH, Tross S, Silberfarb P, Perry M, Comis R, Oster M. Comparative psychological disturbance in patients with pancreatic and gastric cancer. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:982-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;57-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 839] [Cited by in RCA: 832] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Seoud T, Syed A, Carleton N, Rossi C, Kenner B, Quershi H, Anand M, Thakkar P, Thakkar S. Depression Before and After a Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer: Results From a National, Population-Based Study. Pancreas. 2020;49:1117-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Davis NE, Hue JJ, Kyasaram RK, Elshami M, Graor HJ, Zarei M, Ji K, Katayama ES, Hajihassani O, Loftus AW, Shanahan J, Vaziri-Gohar A, Rothermel LD, Winter JM. Prodromal depression and anxiety are associated with worse treatment compliance and survival among patients with pancreatic cancer. Psychooncology. 2022;31:1390-1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Tobias K, Pessin H, Ku GY, Yuan J, Wolchok J. Depression, cytokines, and pancreatic cancer. Psychooncology. 2014;23:339-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mayr M, Schmid RM. Pancreatic cancer and depression: myth and truth. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jarrin Jara MD, Gautam AS, Peesapati VSR, Sadik M, Khan S. The Role of Interleukin-6 and Inflammatory Cytokines in Pancreatic Cancer-Associated Depression. Cureus. 2020;12:e9969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Talar-Wojnarowska R, Gasiorowska A, Smolarz B, Romanowicz-Makowska H, Kulig A, Malecka-Panas E. Clinical significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene polymorphism and IL-6 serum level in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:683-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Shakin EJ, Holland J. Depression and pancreatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1988;3:194-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Green AI, Austin CP. Psychopathology of pancreatic cancer. A psychobiologic probe. Psychosomatics. 1993;34:208-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Brown JH, Paraskevas F. Cancer and depression: cancer presenting with depressive illness: an autoimmune disease? Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:227-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Javadrashid D, Baghbanzadeh A, Derakhshani A, Leone P, Silvestris N, Racanelli V, Solimando AG, Baradaran B. Pancreatic Cancer Signaling Pathways, Genetic Alterations, and Tumor Microenvironment: The Barriers Affecting the Method of Treatment. Biomedicines. 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thillai K, Sarker D, Wells C. PAK4 pathway as a potential therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Future Oncol. 2018;14:579-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Makrilia N, Indeck B, Syrigos K, Saif MW. Depression and pancreatic cancer: a poorly understood link. JOP. 2009;10:69-76. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Passik SD, Breitbart WS. Depression in patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Diagnostic and treatment issues. Cancer. 1996;78:615-626. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF, Noyes R Jr, Doebbeling BN. Relationship between depression and pancreatic cancer in the general population. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:884-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Haddad M. Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: treatment and management. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:1411-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Boyd CA, Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Han Y, Kuo YF, Riall TS. The effect of depression on stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2012;152:403-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pancreatic cancer in adults: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018 Feb- . [PubMed] |

| 29. | Sheibani-Rad S, Velanovich V. Effects of depression on the survival of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2006;32:58-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |