Published online Apr 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i11.2464

Peer-review started: January 11, 2023

First decision: February 17, 2023

Revised: February 23, 2023

Accepted: March 21, 2023

Article in press: March 21, 2023

Published online: April 16, 2023

Processing time: 85 Days and 7.1 Hours

The late presentation of dural tears (LPDT) has a low incidence rate and hidden symptoms and is easily ignored in clinical practice. If the disease is not treated in time, a series of complications may occur, including low intracranial pressure headache, infection, pseudodural cyst formation, and sinus formation. Here, we describe two cases of LPDT.

Two patients had sudden fever 1 wk after lumbar surgery. Physical examination showed obvious tenderness in the operation area. The patients were confirmed as having LPDT by lumbar magnetic resonance imaging and surgical exploration. One case was caused by continuous negative pressure suction and malnutrition, and the other was caused by decreased dural ductility and low postoperative nutritional status. The first symptom of both patients was fever, with occasional headache. Both patients underwent secondary surgery to treat the LPDT. Dural defects were observed and dural sealants were used to seal the dural defects, then drainage tubes were retained for drainage. After the operation, the patients were treated with antibiotics and the patients’ surgical incisions healed well, without fever or incision tenderness. Both recovered and were discharged 1 wk after the operation.

LPDT is a rare complication of spinal surgery or neurosurgery that has hidden symptoms and can easily be overlooked. Since it may cause a series of complications, LPDT needs to be actively addressed in clinical practice.

Core Tip: Late presentation of dural tears (LPDT) has a low incidence rate and hidden symptoms and is easily overlooked in clinical practice. We describe two cases of LPDT in this paper, and summarize the diagnosis, etiologies and treatment strategies of LPDT through a literature review.

- Citation: Xu C, Dong RP, Cheng XL, Zhao JW. Late presentation of dural tears: Two case reports and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(11): 2464-2473

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i11/2464.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i11.2464

Dural tears (DT) in the spinal canal often occur before or during surgery, such as spinal trauma, lumbar puncture, removal of intradural tumors, and complications of spinal surgery. According to literature reports, the incidence of DT due to spinal surgery is 1%–17%[1], which is relatively common, especially in patients with ligament ossification, with an incidence as high as 32%. Postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage is rare, with an incidence of less than 1%[2,3], including unrecognized DT during surgery and late presentation of DT (LPDT). Here, we report two cases of LPDT and provide a comprehensive literature review.

Case 1: A 67-year-old woman complained of headache after continuous vacuum sealing drainage (VSD) for 1 wk.

Case 2: A 61-year-old man complained of headache and fever with a temperature of 38.6 °C 1 wk after lumbar operation.

Case 1: A 67-year-old woman presented to our department with a main complaint of lower back pain and pain in both lower extremities for 2 years. Physical examination showed a body mass index of 21.1 kg/m2, and a positive (40°) bilateral straight leg elevation test. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. As the diagnosis was confirmed, posterior lumbar laminectomy, discectomy, bone graft fusion, and internal fixation were performed. After sufficient hemostasis was achieved, unilateral drainage was retained, and the incision was sutured. The patient was administered anti-inflammatory, rehydration, and anti-infection treatments after the operation. The drainage volume gradually decreased three days after the operation. When the drainage volume was less than 50 mL, the drainage was removed. One week later, the patient had chills and high fever. Considering that infection may have occurred in the operation site, debridement, and continuous VSD were performed. Necrotic tissue was found in the muscle layer and the dura was intact. After the operation, the incision was given continuous saline irrigation and negative pressure suction. After continuous VSD for another week, the patient complained of headache, and the integrity of the VSD was damaged.

Case 2: A 61-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with complaints of lower back pain for more than 15 years, numbness of the right lower extremity for 1 year, and aggravation for 10 d. The patient underwent posterior lumbar laminectomy and interbody fusion surgery after diagnosis. After the operation, neurological symptoms and pain improved markedly. On postoperative day 10, the patient complained of headache and fever with a temperature of 38.6 °C.

Case 1: The patient had a medical history of hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, hepatitis B, and tuberculosis.

Case 2: The patient denied having a history of hypertension, diabetes, or any other comorbidity.

Case 1: Tenderness was noted over the incision and dark-red blood flowed out after local compression on the incision.

Case 2: Tenderness was noted over the incision.

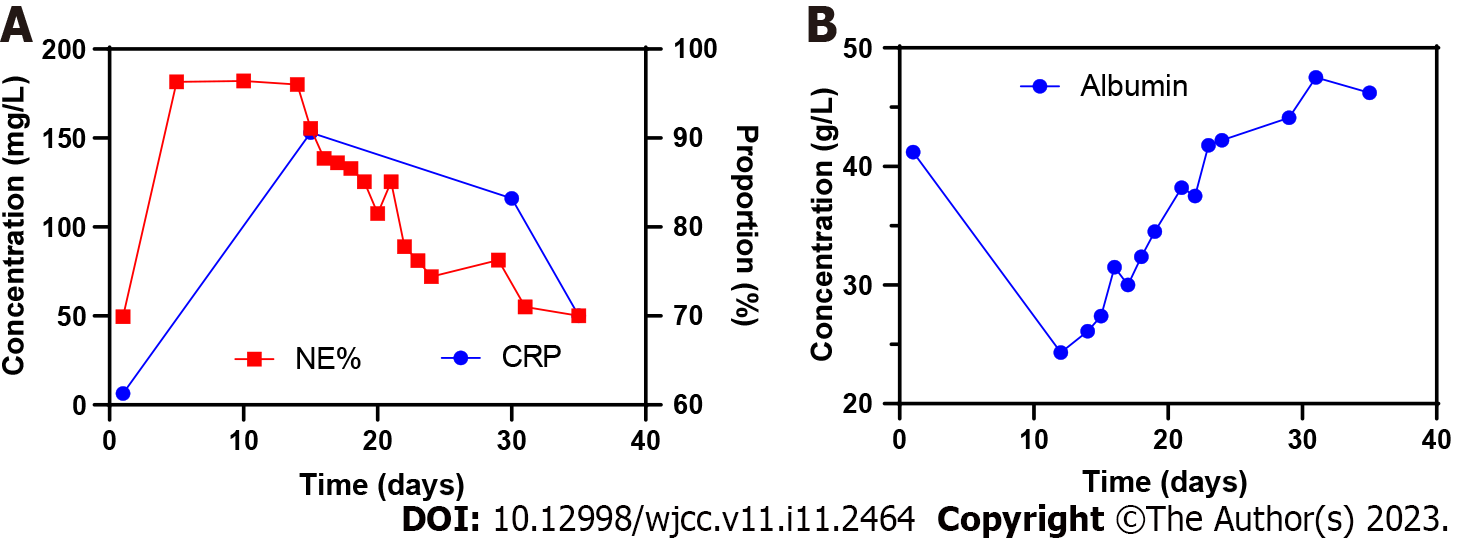

Case 1: Routine blood tests showed the percentage of neutrophils was significantly increased. Increased C-reactive protein levels suggested the possibility of inflammation in the body. Decreased albumin content indicated that the patient was in a state of low nutrition (Figure 1).

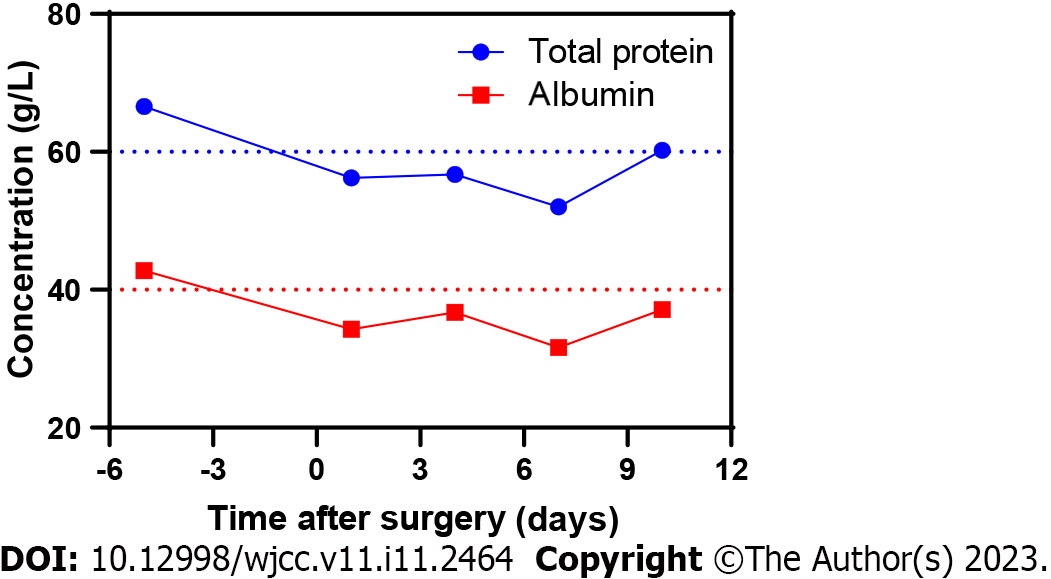

Case 2: Evolution of the patient’s nutritional status after hospitalization is presented in Figure 2, which shows that the patient was in a low nutritional state after posterior lumbar interbody fusion surgery.

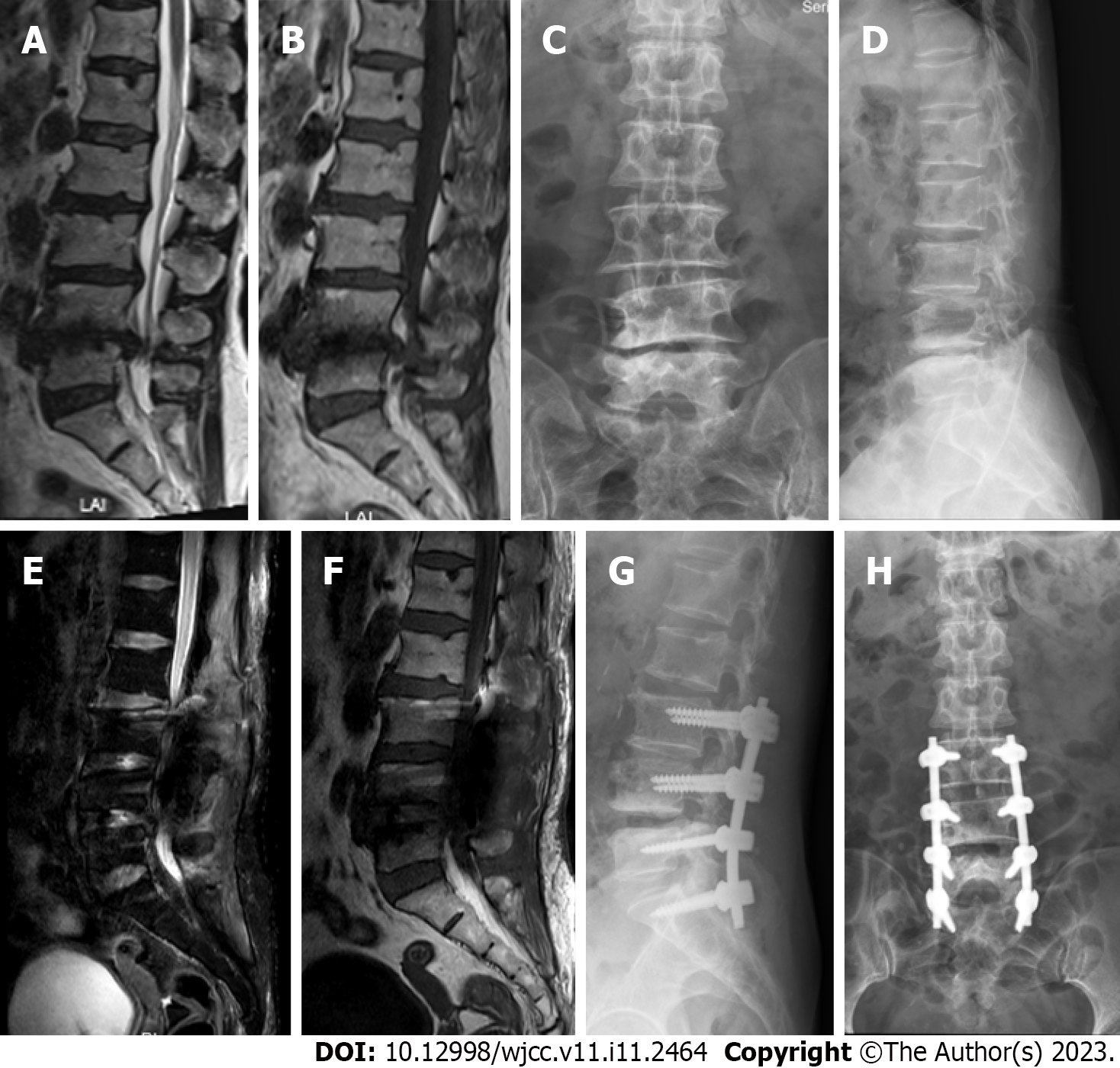

Case 1: As shown in Figure 3, lumbar MRI before the surgery revealed lumbar disc herniation and lumbar spinal stenosis at the L3–S1 level. The MRI after the surgery showed no obvious CSF leakage.

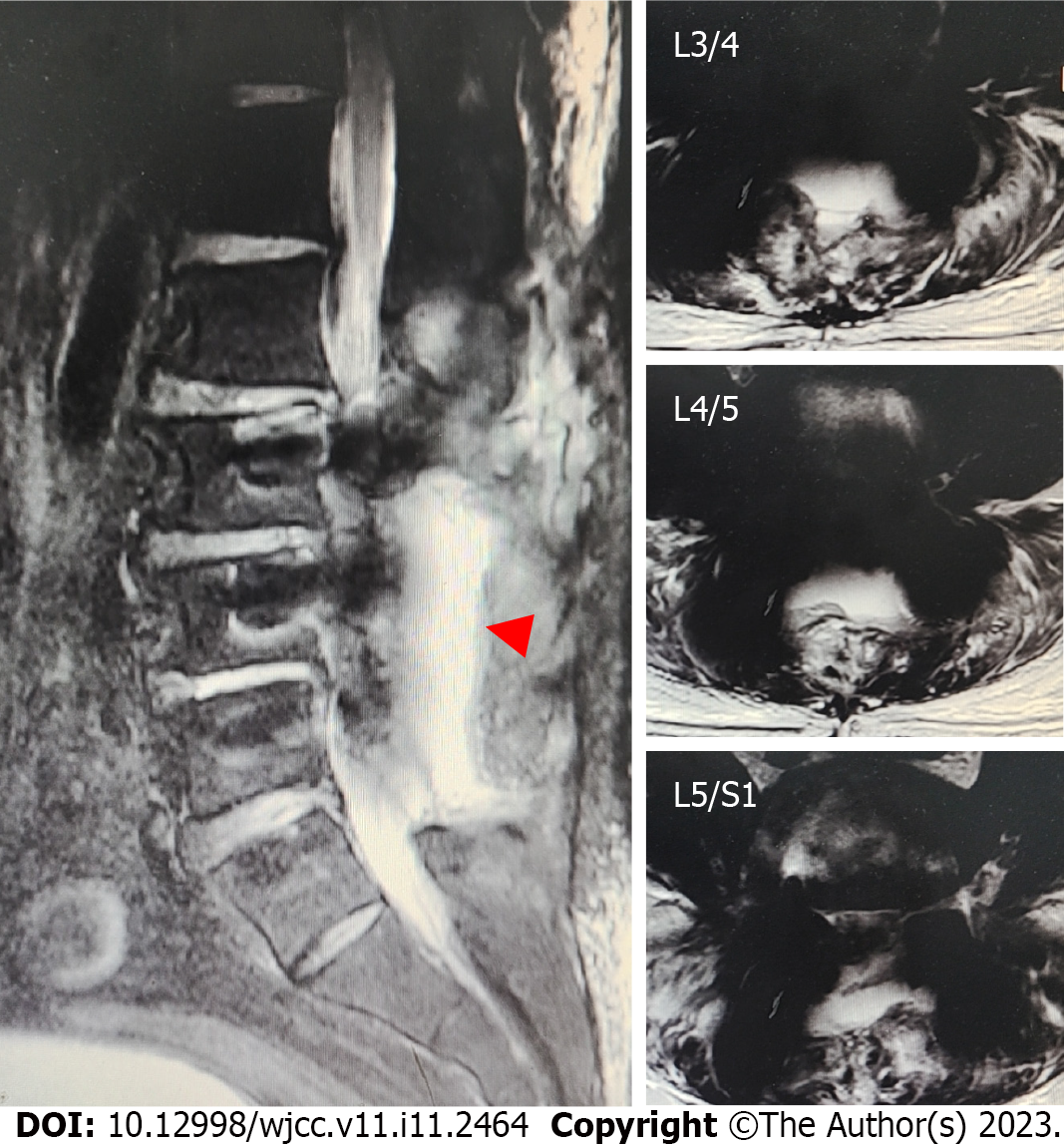

Case 2: Lumbar MRI showed massive long T1 and T2 signals in the soft tissue behind the level of the L3–S1 vertebral body (Figure 4).

Both patients were diagnosed with LPDT.

Case 1: In this case, DT was believed to be caused by continuous VSD. The reasons are as follows: The dura mater (dura) was intact after the first debridement, but CSF leakage was found during the second debridement. No sharp protrusions or bone fragments were observed after lamina decompression. The factors of LPDT caused by VSD in this patient were as follows: (1) The patient’s low nutritional status, coupled with a history of hepatitis B and tuberculosis, was not conducive to tissue repair; and (2) The fascia layer of the incision was infected, the tissue mass was reduced after debridement, and cavities were easily formed, which reduced tissue and muscle function by isolating and sealing the dura.

Case 2: In this case, the patient had a history of lumbar disease for > 15 years. The protruding disc had been pressing the dural sac posteriorly for a long time, resulting in erosion and adhesion of the dura to the posterior ligament tissue. Postoperatively, the patient presented with malnutrition, which slowed the healing of the soft tissue at the incision site. The tissue behind the dura cannot form an effective protective barrier, which reduces the pressure of the dura against the CSF, resulting in a delayed dural tear.

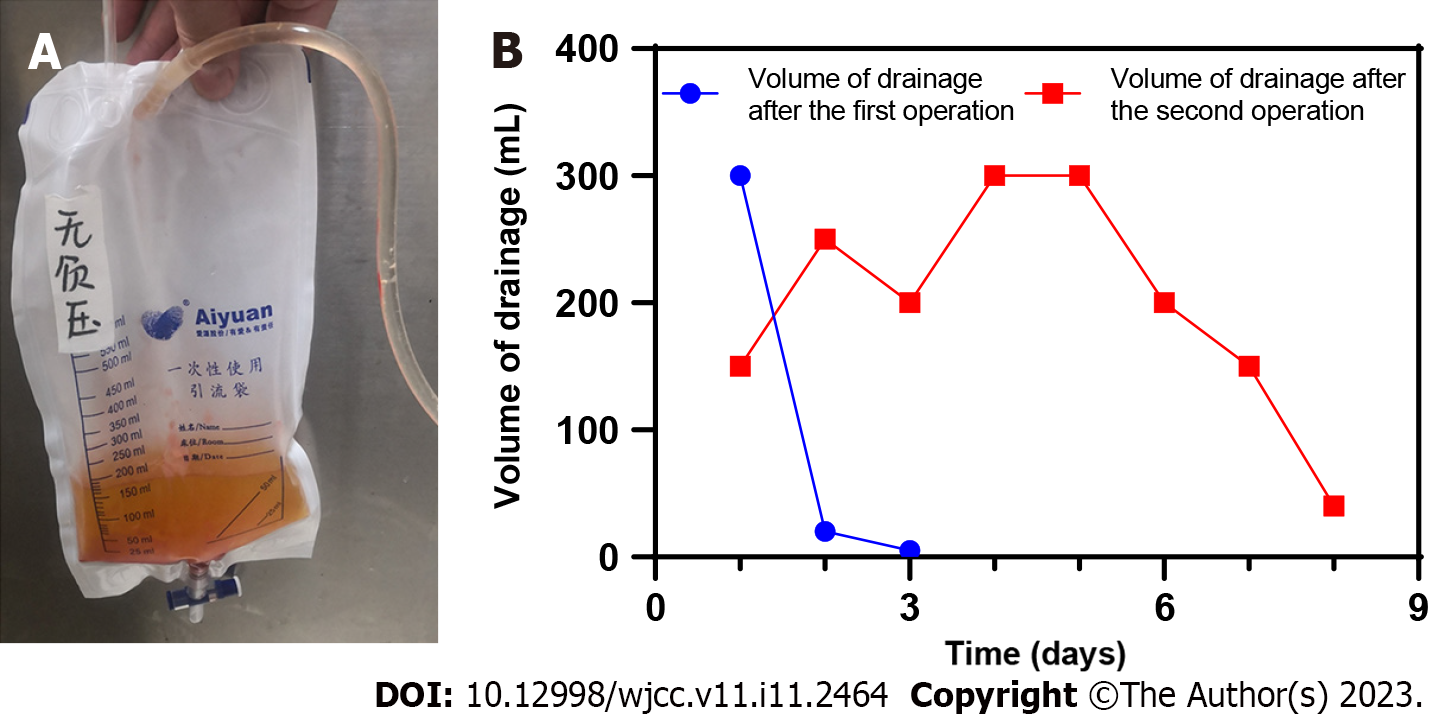

Case 1: The third operation was performed to remove the VSD device and explore the operation area of the spine. After the incision was rinsed with saline during the operation, a small amount of clear liquid flowed out of the dural surface. The dura was explored, and no sharp bone fragments or spurs were found. After the fibrin glue was used for sealing the dural defect, the wound was sutured after inserting the indwelling drainage tube. The drainage fluid and the changes of the drainage volume are shown in Figure 5, and the drainage tube was removed 1 wk after the third surgery.

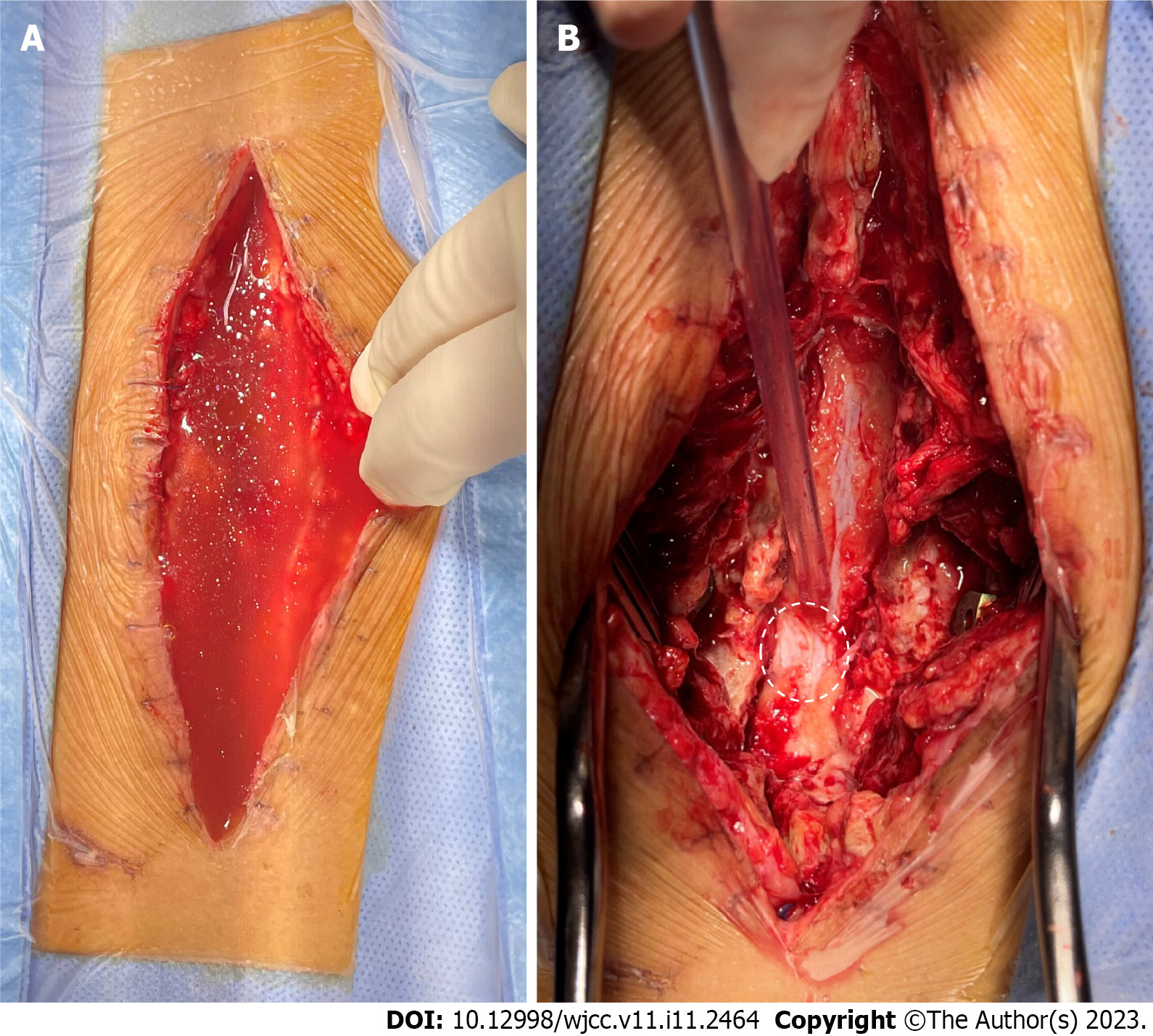

Case 2: Emergency surgical debridement and exploration were performed. After opening the surgical incision, a large amount of clear liquid mixed with blood accumulated in the subcutaneous space. After aspirating the accumulated liquid, damage to the surface of the dorsal dura was observed (Figure 6). We used sutures and dural sealants to treat the dural defects.

The incisions recovered well postoperatively, and the patients were discharged from the hospital. There were no related complications after discharge.

LPDT can easily be ignored because of its late onset and hidden clinical symptoms. In clinical practice, it is often not detected until pseudocysts and sinuses are formed. The complications of LPDT include delayed wound healing, wound infection, soft tissue swelling in the operative area, persistent positional headache, dural cyst formation, prolonged hospital stay, adhesive arachnoiditis, and secondary surgery. LPDT may also cause pneumonia, urinary tract infections, thrombosis, acute kidney injury, pneumocephalus, and pneumorachis[3-5]. The key elements for LPDT diagnosis are presented in Table 1[4,6-10]. Based on our clinical experience, positional headache is an early symptom of LPDT, and should be treated with caution in clinical practice.

| Clinical elements | Characteristics |

| Onset time | 5 d after surgery, even up to 3 mo |

| Symptoms | Headache, dizziness, nausea, and other low intracranial pressure symptoms |

| Drainage fluids, transudates | Clear or light red |

| Imaging characteristics | MRI reveals dura damage, CSF outflow, sinus formation |

| β2-transferrin | + |

According to the mechanism of dural damage, LPDT factors can be divided into three categories: Mechanical penetration, decreased dural resistance to CSF pressure, and increased CSF pressure.

Mechanical penetration: For an unidentified DT occurring during the operation, the injury is usually caused by accidental puncture of the dura when using a syringe needle or suture needle. Sharp bone fragments or bone spurs penetrating the dura are common causes of postoperative LPDT[3,4], and accounts for about 40% of all cases[4]. Therefore, during the operation, the operating table should be adjusted to avoid the residual bone surface damaging the dura. Simultaneously, if possible, an ultrasonic osteotome or grinding drill should be used to remove the vertebral lamina and keep the residual bone surface as flat as possible. Traumatic factors also play an important role in the occurrence of LPDT. Kamochi et al[11] reported two cases of CSF leakage for more than 10 years after head injury.

Decreased dural resistance to CSF pressure: Many factors influence dural resistance to CSF pressure. First, the integrity of the dura is a direct factor. The dura consists of three layers: The dura propria, arachnoid membrane, and soft membrane. Because CSF remains in the subarachnoid space, CSF leakage does not occur when only the dura is injured during the operation and the arachnoid membrane is intact; however, the ability to resist CSF pressure declines. Second, the duration of the operation also affects the resistance of the dura. Studies have confirmed that a long operation time (more than 250 min) leads to an increase in the incidence of LPDT[3]. This is because the dural exposure time is too long and the light irradiation during the operation is too long, resulting in dehydration of the dura. Eventually, the dura becomes less ductile, making it extremely vulnerable[12,13]. Thirdly, tumor radiotherapy and chemotherapy may also be one of the more common factors leading to LPDT[14,15]. Radiation applied in the course of tumor radiotherapy will cause damage to the dura resulting in thinning or necrosis of the dura. Chemotherapeutic drugs, such as dopamine agonists, may also damage the dura. In addition, Glassman et al[16] believe that LPDT is related to bone morphogenetic protein (BMP2), since BMP2 can activate the inflammatory response in vivo, leading to tissue edema. Finally, the patient’s condition also affects LPDT. Advanced age is a high-risk factor[17]. At the same time, connective tissue diseases (Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome) can lead to dural expansion, thus affecting the tough-ness of the dura[18].

Increased CSF pressure: Vigorous activity of the spine after spinal surgery causes significant changes in local CSF pressure. For example, Dannawi et al[8] reported an orgasmic dural tear three months after lumbar surgery. Sneezing, coughing, and other factors increase abdominal pressure, which in turn affects CSF pressure. In addition, obvious cavities after spinal surgery may lead to a lack of supporting structures behind the dura, which will affect the pressure balance between the inner and outer dura, and finally show an increase in the local CSF pressure in the cavity[19-21].

The treatment of LPDT is often more complicated and difficult than DT that occurs during surgery, because when LPDT is found, sinuses or pseudocysts are generally formed. Initial treatment can be conservative, and surgical repair may be required when the effect is poor[1].

Conservative treatment: Although the incidence of LPDT is low, it deserves the attention of clinicians, since it affects patient satisfaction with medical treatment and clinical efficacy. When the symptoms are not serious, conservative treatment is preferred, including bed rest, prevention of infection, rehydration, nutrition, and local pressure bandage of the wound, among others[1]. There is currently much debate about the treatment strategy of bed rest, and the results of some studies have revealed that bed rest has little clinical benefit, while increasing medical costs and length of hospital stay. According to literature reports and clinical experience, our research group believes that the necessity and duration of bed rest mainly depend on the size and location of the dural defect and the clinical symptoms of the patient.

Surgical treatment: When conservative treatment fails within three days to a week, surgical treatment is considered necessary, especially in the case of wound infection and sinus and pseudodural cyst formation. There is evidence that successful repair of the dura can effectively reduce the occurrence of complications caused by dural defects[19,22,23]. The main focus of clinical treatment is to effectively and quickly block dural defects. Studies have confirmed that watertight closure is key to the treatment of CSF leakage caused by dural defects[24,25]. The current clinical treatment measures for dural defects vary according to their location and size, mainly including closure with medical sutures or non-penetrating titanium clamps, autologous tissue filling, and sealing with tissue sealants.

Sutures. The traditional treatment philosophy holds that suture closure is the gold standard for the treatment of dural defects[26]. This technique is still one of the main treatment strategies favored by spinal surgeons and neurosurgeons for dural defects, but many difficulties exist: The location of the defect may not be conducive to suturing or cannot be sutured; CSF leakage cannot be avoided in the pinhole left by the suture needle; and it is even possible that the defect area is transformed from a low-pressure area to a high-pressure area because of the suture technique.

Non-penetrating titanium clamp: A non-penetrating titanium clip designed for vascular anastomosis is another option for DT[27-29]. Its clinical use does not produce pinholes, which solves the risk of CSF leakage caused by pinholes. At present, it is considered to have the advantages of a simple operation, rapid process, less postoperative adhesion, less dural exposure and reduced potential risk of CSF leakage. However, because it is made of metal, we must consider metal artifacts that may affect the diagnosis and treatment of the disease in the future. At the same time, issues regarding the use of non-penetrating titanium clips such as clip displacement, inability to be reused during operations, high medical cost, being non-degradable, and subsequent DT also need to be considered.

Autologous tissue: The materials used to fill the dural defect include the periosteum, fascia, fat, muscle, and other tissues. First, the effectiveness of the fascia and other autologous tissues in blocking dural defects was confirmed in animal models[30]. A clinical study of the human body observed the curative effect of repairing dural defects with autologous tissue, and the results confirmed that it can block the dural defect effectively[31-34]. Use of autologous tissue to repair dural defects has the advantages of the lack of infection, rejection, disease transmission, and increase in patient burden. However, additional surgery using local materials increases the surgical trauma, operation time, and adhesion risk. Furthermore, postoperative adhesion is a major factor affecting clinical efficacy.

Sealants: Currently, the commercial synthetic materials used for dural defects are mainly absorbable and degradable materials, which can roughly be divided into three categories: Polyethylene glycol (PEG), hydrogels (such as DuraSeal), fibrin glue (Tissel, Evicel, and Beixiu glue), and hydrogels formed by glutaraldehyde and bovine serum albumin (such as BioGlue surgical adhesives)[35]. According to a multicenter, prospective, and randomized study, PEG hydrogel sealant is not inferior to common dural sealing technology[36]. However, current clinical research has found that PEG hydrogels can cause significant swelling in clinical use, which is extremely unfavorable for the spinal canal or ventricle with limited space[37]; fibrin glue itself can quickly form glue, but it cannot form strong adhesions with the tissue surface, therefore, it cannot resist the fluctuating pressure of CSF at the physiological level; at the same time, the BioGlue adhesive was found to have neurotoxicity. Therefore, more powerful adhesives are expected to be successfully prepared in the future.

Based on the defects of a single treatment strategy, two or a combination of two schemes is often used in the clinic. A Canadian questionnaire showed that, as the size of the defect gradually increases, clinicians gradually adopt a combination of treatment regimens[38].

The primary role of perioperative management in LPDT is prevention. First, we attempted to choose an operation method that causes less damage to the peridural tissue. The peridural ligaments, lamina, and even posterior muscle groups can provide protection to the dura and reduce the risk of dural damage[3,39]. Therefore, a treatment strategy for minimally invasive surgery should be preferred if the condition permits. In addition, from the perspective of medical safety and the possibility of LPDT, clinicians should clearly inform patients and their families of the risk when signing the operation before surgery and provide them with a prior understanding of the possible complications. This is because there are many claims of malpractice related to accidental durotomy caused by spinal surgery.

LPDT as a rare complication in spinal surgery or neurosurgery, has hidden symptoms and is easily overlooked. If the complication cannot be treated in time, it may cause a series of adverse consequences, including pseudodural cyst and sinus. Therefore, it needs to be actively addressed in clinical practice, through careful examination during surgery and active preventive measures after surgery.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nambi G, Saudi Arabia; Zharikov YO, Russia S-Editor: Zhao S L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Kalidindi KKV, Bhat MR, Mannem A, Chhabra HS. Conservative Management for Late Presenting Dural Tears After Spine Surgery: An Institutional Experience and Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2020;134:e82-e92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Park JS, Kong DS, Lee JA, Park K. Intraoperative management to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leakage after microvascular decompression: dural closure with a "plugging muscle" method. Neurosurg Rev. 2007;30:139-42; discussion 142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Durand WM, DePasse JM, Kuris EO, Yang J, Daniels AH. Late-presenting dural tear: incidence, risk factors, and associated complications. Spine J. 2018;18:2043-2050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Khazim R, Dannawi Z, Spacey K, Khazim M, Lennon S, Reda A, Zaidan A. Incidence and treatment of delayed symptoms of CSF leak following lumbar spinal surgery. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:2069-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gupta M, Kumar Varma KK, Singh Chhabra H. A rare case of concomitant pneumocephalus and pneumorachis after lumbar spine surgery with late presenting dural leak. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2019;5:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hawk MW, Kim KD. Review of spinal pseudomeningoceles and cerebrospinal fluid fistulas. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Epstein NE. A review article on the diagnosis and treatment of cerebrospinal fluid fistulas and dural tears occurring during spinal surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:S301-S317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Dannawi Z, Lennon SE, Zaidan A, Khazim R. Orgasmic dural tear: an unusual delayed presentation of postural headache following lumbar discectomy. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bachmann-Harildstad G. Diagnostic values of beta-2 transferrin and beta-trace protein as markers for cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Rhinology. 2008;46:82-85. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lauer KK, Haddox JD. Epidural blood patch as treatment for a surgical durocutaneous fistula. J Clin Anesth. 1992;4:45-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kamochi H, Kusaka G, Ishikawa M, Ishikawa S, Tanaka Y. Late onset cerebrospinal fluid leakage associated with past head injury. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2013;53:217-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Narotam PK, José S, Nathoo N, Taylon C, Vora Y. Collagen matrix (DuraGen) in dural repair: analysis of a new modified technique. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:2861-7; discussion 2868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kinaci A, Van Doormaal TPC. Dural sealants for the management of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after intradural surgery: current status and future perspectives. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2019;16:549-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ogawa Y, Tominaga T. Delayed cerebrospinal fluid leakage 10 years after transsphenoidal surgery and gamma knife surgery - case report - . Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2007;47:483-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee JJ, Kim HY, Dhong HJ, Chung SK, Kong DS, Nam DH, So YK, Hong SD. Delayed Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage After Treatment of Skull Base Tumors: Case Series of 9 Patients. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:e591-e598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Glassman SD, Gum JL, Crawford CH 3rd, Shields CB, Carreon LY. Complications with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in posterolateral spine fusion associated with a dural tear. Spine J. 2011;11:522-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sin AH, Caldito G, Smith D, Rashidi M, Willis B, Nanda A. Predictive factors for dural tear and cerebrospinal fluid leakage in patients undergoing lumbar surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schievink WI. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension. JAMA. 2006;295:2286-2296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 667] [Cited by in RCA: 693] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang JC, Bohlman HH, Riew KD. Dural tears secondary to operations on the lumbar spine. Management and results after a two-year-minimum follow-up of eighty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1728-1732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Papavero L, Engler N, Kothe R. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery: first aid in ten steps. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:2077-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jito J, Nitta N, Nozaki K. Delayed cerebrospinal fluid leak after watertight dural closure with a polyethylene glycol hydrogel dural sealant in posterior fossa surgery: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2014;54:634-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liang H, Li C, Gao A, Liang P, Shao Y, Lin T, Zhang X. Spinal duraplasty with two novel substitutes restored locomotor function after acute laceration spinal cord injury in rats. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2012;100:2131-2140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Song Y, Li S, Song B, Zhang Y, Gao W, Li N, Fan K, Ma J. The pathological changes in the spinal cord after dural tear with and without autologous fascia repair. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:1531-1540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Esposito F, Angileri FF, Kruse P, Cavallo LM, Solari D, Esposito V, Tomasello F, Cappabianca P. Fibrin Sealants in Dura Sealing: A Systematic Literature Review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ikeme S, Weltert L, Lewis KM, Bothma G, Cianciulli D, Pay N, Epstein J, Kuntze E. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a sealing hemostat patch (HEMOPATCH) vs standard of care in cardiac surgery. J Med Econ. 2018;21:273-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cammisa FP Jr, Girardi FP, Sangani PK, Parvataneni HK, Cadag S, Sandhu HS. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:2663-2667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kaufman BA, Matthews AE, Zwienenberg-Lee M, Lew SM. Spinal dural closure with nonpenetrating titanium clips in pediatric neurosurgery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010;6:359-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Marin Laut FM, Gómez Cárdenas EA, Dormido JR, Molina NM, López López JA. Spinal dural closure without suture: Minimizing the risk of CSF leakage with a flat non-penetrating titanium U-clip. Neurocirugia (Astur : Engl Ed). 2019;30:173-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cheng YP, Lin PY, Huang AP, Cheng CY, Chen CM, Hueng DY. Durotomy repair in minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion by nonpenetrating clips. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Oğretmenoğlu O, Akyol G. The repair of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: comparison of histopathologic findings with cadaveric human temporal fascia, dura mater, and autologous fascia in a rabbit model. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2004;13:1-8. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Barrientos S, Leif M, Hon HH, Aizenberg M, Wong S. Duraplasty Using Autologous Fascia Lata and Latissimus Dorsi Free Flap for Chronic Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30:e671-e674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zha W, Xu M, Zhang L. [Reparation and restitution of head tissue deletion with fascia lata and local flap]. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2013;27:1191-1192. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Fiorindi A, Gioffrè G, Boaro A, Billeci D, Frascaroli D, Sonego M, Longatti P. Banked Fascia Lata in Sellar Dura Reconstruction after Endoscopic Transsphenoidal Skull Base Surgery. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2015;76:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yang HA, Sun SC, Zheng XR, Ding F, Bie YF. Effect of subdural muscle packing in repairing dura mater after retrosigmoid craniotomy. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520910299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Epstein NE. Dural repair with four spinal sealants: focused review of the manufacturers' inserts and the current literature. Spine J. 2010;10:1065-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Osbun JW, Ellenbogen RG, Chesnut RM, Chin LS, Connolly PJ, Cosgrove GR, Delashaw JB Jr, Golfinos JG, Greenlee JD, Haines SJ, Jallo J, Muizelaar JP, Nanda A, Shaffrey M, Shah MV, Tew JM Jr, van Loveren HR, Weinand ME, White JA, Wilberger JE. A multicenter, single-blind, prospective randomized trial to evaluate the safety of a polyethylene glycol hydrogel (Duraseal Dural Sealant System) as a dural sealant in cranial surgery. World Neurosurg. 2012;78:498-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Thavarajah D, De Lacy P, Hussain R, Redfern RM. Postoperative cervical cord compression induced by hydrogel (DuraSeal): a possible complication. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E25-E26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Oitment C, Aref M, Almenawar S, Reddy K. Spinal Dural Repair: A Canadian Questionnaire. Global Spine J. 2018;8:359-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kundu A, Sano Y, Pagel PS. Case report: delayed presentation of postural headache in an adolescent girl after microscopic lumbar discectomy. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55:696-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |