Published online Apr 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2343

Peer-review started: December 21, 2022

First decision: January 5, 2023

Revised: January 12, 2023

Accepted: March 6, 2023

Article in press: March 6, 2023

Published online: April 6, 2023

Processing time: 99 Days and 10.4 Hours

Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) colitis is one of the most common infections in hospitalized patients, characterized by fever and diarrhea. It usually improves after appropriate antibiotic treatment; if not, comorbidities should be considered. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis is a possible co-existing diagnosis in patients with C. difficile infection with poor treatment response. However, compared with immunocompromised patients, CMV colitis in immunocompetent patients is not well studied.

We present an unusual case of co-existing CMV colitis in an immunocompetent patient with C. difficile infection. An 80-year-old female patient was referred to the infectious disease department due to diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and fever for 1 wk during her hospitalization for surgery. C. difficile toxin B polymerase chain reaction on stool samples was positive. After C. difficile infection was diagnosed, oral vancomycin treatment was administered. Her symptoms including diarrhea, fever and abdominal discomfort improved for ten days. Unfortunately, the symptoms worsened again with bloody diarrhea and fever. Therefore, a sigmoidoscopy was performed for evaluation, showing a longitudinal ulcer on the sigmoid colon. Endoscopic biopsy confirmed CMV colitis, and the clinical symptoms improved after using ganciclovir.

Co-existing CMV colitis should be considered in patients with aggravated C. difficile infection on appropriate treatment, even in immunocompetent hosts.

Core Tip: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis is rare in immunocompetent patients, but colitis is the main clinical manifestation. The Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infection and CMV colitis symptoms might be indistinguishable clinically. Therefore, it is difficult to consider their co-existence in patients suspected of C. difficile infection. If a patient treated with C. difficile infection does not show clinical improvement, the possibility of co-existing CMV colitis should be considered as one of the differential diagnoses. Sigmoidoscopy with biopsy is crucial in diagnosing co-existing CMV and C. difficile infection colitis.

- Citation: Kim JH, Kim HS, Jeong HW. Coexisting cytomegalovirus colitis in an immunocompetent patient with Clostridioides difficile colitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(10): 2343-2348

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i10/2343.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2343

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a member of the herpesvirus family and forms latent infection after the resolution of the primary infection[1]. CMV primary infection can cause mononucleosis-like symptoms in immunocompetent adults[1]. After the primary CMV infection, CMV remains in host cells and CMV replication is controlled by the immune system in immunocompetent patients[1]. Immunodeficiency is the leading risk factor for invasive CMV diseases[2]. Invasive CMV diseases can occur in immunocompromised patients, including transplant recipients or patients with HIV, by primary infection or reactivation and could have significant morbidity and mortality[3]. This mostly affects the gastrointestinal tract, comprising 30% of tissue-invasive CMV diseases in immunocompromised patients[4]. Clinical manifestation of CMV colitis in immunocompromised patients varies and depends on the site of involvement which could cause odynophagia, abdominal pain, hematochezia, and fever[4].

CMV colitis in immunocompetent patients was previously considered very rare. However, there has been an increasing number of case reports in immunocompetent patients[5,6]. The symptoms of CMV colitis in immunocompetent patients also present odynophagia, abdominal pain, hematochezia, and fever[5,6]. However, its epidemiology, clinical features, and outcomes in immunocompetent patients are not completely understood[4-8].

Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) colitis is a cause of diarrhea in hospitalized patients and is one of the most common causes of nosocomial infections[9]. C. difficile infection is usually suspected when hospitalized patients develop diarrhea and fever[9]. CMV colitis symptoms are clinically indistinguishable from those of C. difficile infection. Therefore, if the immunocompromised status of patients who develop C. difficile infection does not improve even with appropriate treatment, accompanying CMV colitis should be considered. However, this may not be considered in immunocompromised patients because cases of co-existing C. difficile infection and CMV colitis are rare in immunocompetent patients. We report an unusual case of CMV colitis in an immunocompetent C. difficile infection patient with literature review.

An 80-year-old female patient was referred for an infectious disease (ID) consult due to diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and fever for 1 wk during her rehabilitation treatment after spinal stenosis surgery.

She underwent spinal stenosis surgery three weeks ago for back pain. She took methylprednisolone 250 mg per day for a week from the time of surgery due to paralysis of the lower extremities associated with spinal stenosis. She was treated with piperacillin/tazobactam for 7 d and cefixime for 4 d for a urinary tract infection before ID consultation. She had diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and fever for 1 wk. C. difficile toxin A, B polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were performed on stool samples. C. difficile toxin B PCR was positive. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen/pelvis showed diffuse wall thickening in the rectum with mild perirectal infiltration in the upstream colon. The patient was treated with oral vancomycin 250 mg every 6 h for 10 d, after which fever and diarrhea improved for ten days. However, the symptoms worsened again with bloody diarrhea and fever.

She had a medical history of hypertension and diabetes.

The patient had no family history.

Vital signs were a temperature of 37.8 °C, blood pressure of 110/60 mmHg, pulse rate of 84 beats/min, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min on the consultation day. The patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale score was 15. She had hyperactive bowel sounds, no tenderness or rebound tenderness, no abdominal distension.

On the consultation day, laboratory evaluation revealed anemia (Hb = 9.5 g/dL), an increased level of C-reactive protein (7.3 mg/dL), and an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (61 mm/h) with a normal white blood cell counts of 9730 cell/mm3 (neutrophils = 80%, lymphocyte = 15%). Stool culture for Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., and Escherichia coli O-157:H7 was negative. In routine stool examination, there is no helminth or protozoa, and stool white blood cell counts are 1-5 cell/high power field.

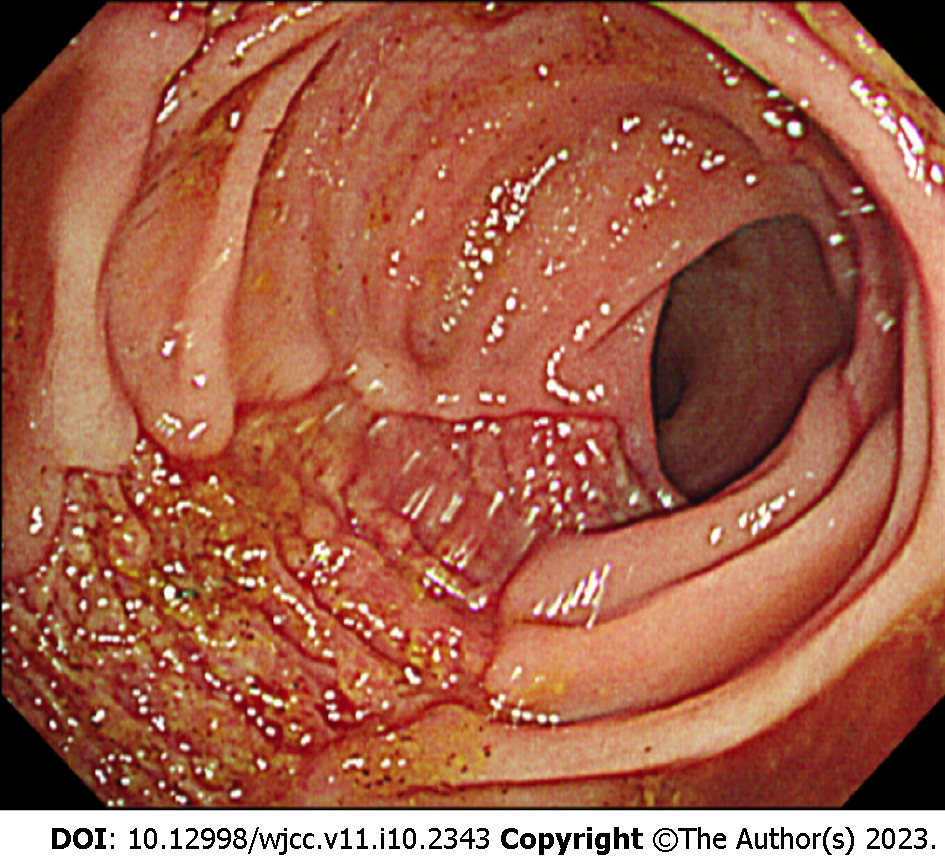

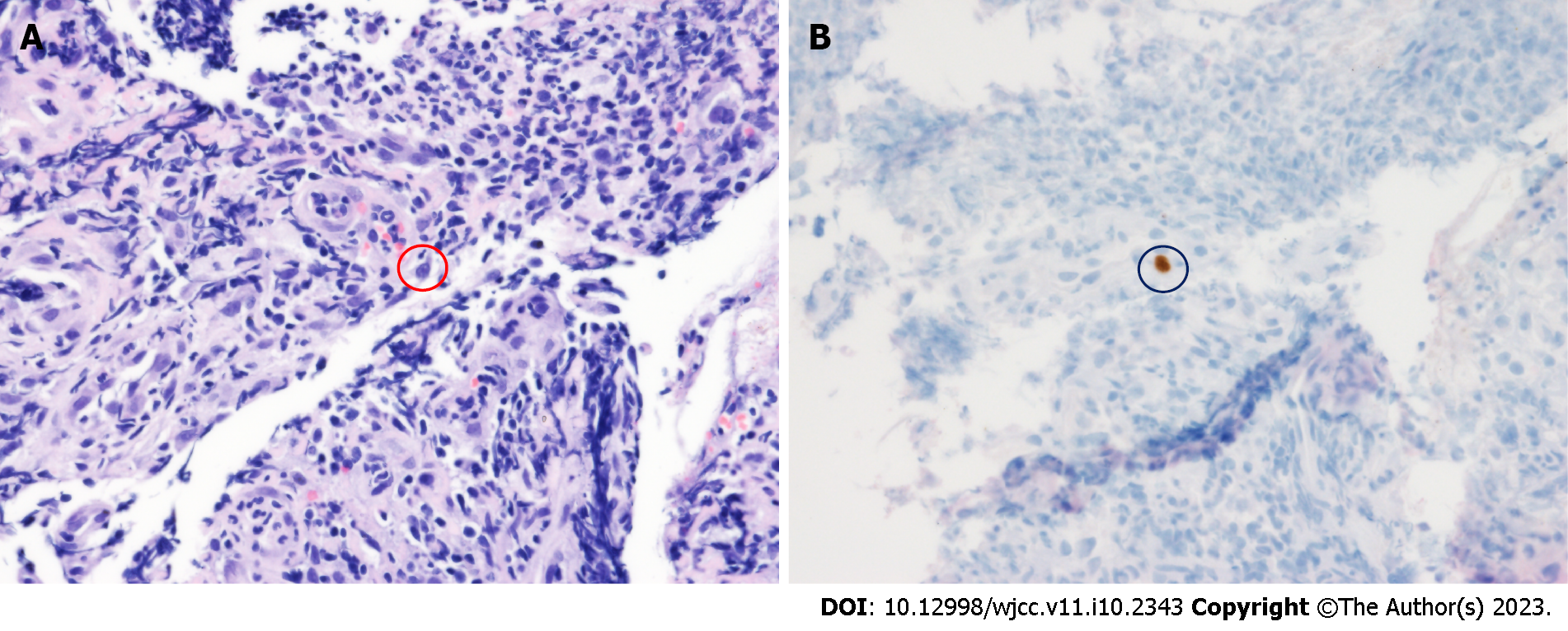

Flexible sigmoidoscopy showed a longitudinal ulcer from the anal verge (AV) to 12 cm above the AV (Figure 1). The biopsy was performed on the ulcer site. Cells with basophilic intranuclear inclusion body surrounded by a clear halo on hematoxylin and eosin stain and positive immunohistochemistry for CMV (Figure 2).

Co-existing CMV colitis with C. difficile colitis.

Antiviral treatment with intravenous ganciclovir (10 mg/kg/day) was initiated. Fever and bloody diarrhea improved after 5 d of using ganciclovir, and the treatment was continued for 3 wk.

A sigmoidoscopy performed after the treatment showed an improvement in the ulcer lesion, and a biopsy performed 1 mo after the treatment showed negative findings. The patient was discharged to a nursing home after successful treatment with improved symptoms.

Although CMV infection in immunocompetent hosts has been considered rare, one review article retrieved 89 articles reporting on severe CMV infection in immunocompetent adults from 1950 to 2007[10]. They were mainly gastrointestinal and central nervous system diseases. Symptoms of CMV infection in immunocompetent patients are not well documented; however, severe life-threatening CMV infections in immunocompetent hosts might not be such a rare condition as was previously thought[10]. Currently, a rapidly rising number of literature cases worldwide indicate that CMV infections can also be observed in immunocompetent patients with altered immune status such as steroid use[8,11]. A total of 51 immunocompetent patients were diagnosed with CMV colitis between January 1995 and February 2014 at a tertiary care university hospital in South Korea, with 36 cases diagnosed after 2008, suggesting the growing number of immunocompetent CMV patients[8]. Similarly, 42 immunocompetent patients were diagnosed between April 2002 and December 2016 at a hospital in Taiwan[11]. Ko et al[8] reported that risk factors of CMV colitis in immunocompetent patients were steroid use and RBC transfusion within 1 mo. Our patient also received steroid treatment, and this could be the risk factor of CMV colitis. Wetwittayakhlang et al[5] compared clinical features and endoscopic findings of gastrointestinal CMV diseases between immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients and found that immunocompetent patients were older and had more GI bleeding and shorter symptom period than immunocompromised patients[5]. Small bowel involvement was more frequent in the immunocompetent group[5]. Chaemsupaphan et al[6] also reported that most immunocompetent patients presented with gastrointestinal bleeding compared to immunocompromised patients[6]. In another study by Yoon et al[7], CMV gastroenterocolitis of immunocompetent patients occurred in older patients with comorbidities and had various endoscopic features such as discrete ulcer type and diffuse edematous type with no association with clinical outcomes[7].

C. difficile infection is a common cause of colitis in hospitalized patients. Although there are variations according to region and year by year, C. difficile infection occurs in approximately 10 cases per 1000 hospitalization days[12]. Clinical manifestations of C. difficile infection vary from mild diarrhea to life-threatening conditions such as toxic megacolon and bowel perforation[12]. Patients with mild C. difficile infection often recovered 5 to 10 d after stopping antibiotics[13]. However, fulminant C. difficile infection could occur in approximately 1% to 3% of patients[13]. Generally, patients with C. difficile infection are known to recover after 10-14 d of treatment[13,14]. Currently, the diagnosis of C. difficile infection is based on detection of C. difficile toxins and glutamate dehydrogenase with enzyme immunoassay or nucleic acid amplification test[13]. Endoscopy is not recommended in patients with typical C. difficile infection confirmed by laboratory tests and clinical features[13]. However, endoscopic evaluation is recommended if diagnostic problems occur such as clinically suspected C. difficile infection with negative laboratory test, if there was no response to treatment, or when an alternative diagnosis is suspected[13]. Our patient underwent endoscopy because of worsening symptoms gained after the C. difficile infection treatment for 10 d. As C. difficile infection and CMV colitis have similar symptoms, it is difficult to differentiate them simply based on the symptoms. However, severe watery diarrhea is more characteristic of C. difficile infection and bloody diarrhea or sometimes massive bleeding in CMV colitis[15]. In our case, the patient developed worsening bloody diarrhea with fever; we performed endoscopy and the biopsy confirmed CMV colitis.

Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of co-existing CMV colitis in patients with C. difficile infection, even in those with immunocompetent status, especially if patients do not respond to the C. difficile infection treatment. Early endoscopy could help diagnose the possible co-existing CMV colitis in patients with refractory C. difficile infection.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Faraji N, Iran; Gao C, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Picarda G, Benedict CA. Cytomegalovirus: Shape-Shifting the Immune System. J Immunol. 2018;200:3881-3889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yerushalmy-Feler A, Padlipsky J, Cohen S. Diagnosis and Management of CMV Colitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2019;21:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Griffiths P, Reeves M. Pathogenesis of human cytomegalovirus in the immunocompromised host. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:759-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 88.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fakhreddine AY, Frenette CT, Konijeti GG. A Practical Review of Cytomegalovirus in Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:6156581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wetwittayakhlang P, Rujeerapaiboon N, Wetwittayakhlung P, Sripongpun P, Pruphetkaew N, Jandee S, Chamroonkul N, Piratvisuth T. Clinical Features, Endoscopic Findings, and Predictive Factors for Mortality in Tissue-Invasive Gastrointestinal Cytomegalovirus Disease between Immunocompetent and Immunocompromised Patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2021;2021:8886525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chaemsupaphan T, Limsrivilai J, Thongdee C, Sudcharoen A, Pongpaibul A, Pausawasdi N, Charatcharoenwitthaya P. Patient characteristics, clinical manifestations, prognosis, and factors associated with gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoon J, Lee J, Kim DS, Lee JW, Hong SW, Hwang HW, Hwang SW, Park SH, Yang DH, Ye BD, Myung SJ, Jung HY, Yang SK, Byeon JS. Endoscopic features and clinical outcomes of cytomegalovirus gastroenterocolitis in immunocompetent patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ko JH, Peck KR, Lee WJ, Lee JY, Cho SY, Ha YE, Kang CI, Chung DR, Kim YH, Lee NY, Kim KM, Song JH. Clinical presentation and risk factors for cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:e20-e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Balsells E, Shi T, Leese C, Lyell I, Burrows J, Wiuff C, Campbell H, Kyaw MH, Nair H. Global burden of Clostridium difficile infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2019;9:010407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rafailidis PI, Mourtzoukou EG, Varbobitis IC, Falagas ME. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in apparently immunocompetent patients: a systematic review. Virol J. 2008;5:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chan KS, Yang CC, Chen CM, Yang HH, Lee CC, Chuang YC, Yu WL. Cytomegalovirus colitis in intensive care unit patients: difficulties in clinical diagnosis. J Crit Care. 2014;29:474.e1-474.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Turner NA, Grambow SC, Woods CW, Fowler VG Jr, Moehring RW, Anderson DJ, Lewis SS. Epidemiologic Trends in Clostridioides difficile Infections in a Regional Community Hospital Network. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1914149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Czepiel J, Dróżdż M, Pituch H, Kuijper EJ, Perucki W, Mielimonka A, Goldman S, Wultańska D, Garlicki A, Biesiada G. Clostridium difficile infection: review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:1211-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 462] [Article Influence: 77.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guery B, Galperine T, Barbut F. Clostridioides difficile: diagnosis and treatments. BMJ. 2019;366:l4609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chan KS, Lee WY, Yu WL. Coexisting cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients with Clostridium difficile colitis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49:829-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |