Published online Apr 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2315

Peer-review started: December 13, 2022

First decision: February 8, 2023

Revised: February 18, 2023

Accepted: March 10, 2023

Article in press: March 10, 2023

Published online: April 6, 2023

Processing time: 107 Days and 9.3 Hours

Chronic subdural effusion is very common in the cranial imaging of middle-aged and older people. Herein, we report a patient misdiagnosed with subdural effusion, who was eventually diagnosed with chronic subdural empyema (SDE) caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae.

A 63-year-old man was brought to our emergency room with a headache, vomiting, and disturbed consciousness. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a bilateral subdural effusion at the top left side of the frontal lobe. Cerebrospinal fluid examination after lumbar puncture indicated suppurative meningitis, which improved after anti-infective therapy. However, the patient then presented with acute cognitive dysfunction and right limb paralysis. Repeat CT showed an increase in left frontoparietal subdural effusion, disappearance of the left lateral ventricle, and a shift of the midline to the right. Urgent burr hole drainage showed SDE that was culture-positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae. His condition improved after adequate drainage and antibiotic treatment.

Patients with unexplained subdural effusion, especially asymmetric subdural effusion with intracranial infection, should be assessed for chronic SDE. Early surgical treatment may be beneficial.

Core Tip: Detection of chronic subdural effusion is very common in the cranial imaging of middle-aged and older people. Herein, we report a patient misdiagnosed with subdural effusion, who was eventually diagnosed with chronic subdural empyema (SDE) caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Patients with unexplained subdural effusion, especially asymmetric subdural effusion with intracranial infection, should be assessed for chronic SDE. Early surgical treatment may be beneficial.

- Citation: Yang RX, Chen B, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Xie S, He L, Shi J. Development of subdural empyema from subdural effusion after suppurative encephalitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(10): 2315-2320

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i10/2315.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2315

Subdural empyema (SDE) is a rare but potentially fatal infection that involves collection of pus in the subdural space between the dura and the arachnoid. This condition was previously termed a subdural abscess, cortical abscess, purulent dura mater, mucoid meningitis, and subdural suppuration. Most commonly, SDE is caused by sinusitis, otitis media, or upper respiratory tract infections. The infection can spread directly from adjacent sources (most commonly meningitis)[1] or from distant blood sources[2]. Because the subdural space is continuous and has no anatomical barrier, SDE can spread between both cerebral hemispheres. Specific symptoms may include disturbed consciousness and/or other focal neurological deficits, in addition to generalized underlying symptoms such as fever, headaches, seizures, and altered consciousness[3]. Because the skull is a closed cavity, intracranial SDE can also lead to severe symptoms and even death from direct compression and brain damage[4]. After reviewing the current literature, only five cases of Streptococcus pneumoniae SDE have been reported worldwide since 2006 (Table 1). Herein, we report a case initially diagnosed with meningoencephalitis caused by streptococcus pneumoniae, but who was eventually found to have an SDE. The patient was treated with burr hole drainage and intravenous antibiotics, and his condition improved.

| Ref. | Publication | Age (years)/gender | Risk factor | Symptoms | Causative organism | Surgery |

| Hicdonmez et al[17], 2006 | 1 | 1.5/Female | Young age | Fever, lethargy, and inability to walk | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Craniotomy |

| Hoshina et al[18], 2008 | 2 | 1/Male | Young age | Fever, convulsions | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Burr holedrainage |

| Jorgensen et al[19], 2010 | 3 | 1.1/Male | Young age, choroid plexus carcinoma | Diarrhoea, vomiting, coryzal symptoms, and persistent pyrexia | Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6A | Craniotomy |

| Kagami et al[20], 2011 | 4 | 68/Female | Acute subdural hematoma | Fever, headache, coma | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Burr hole drainage |

| Greve et al[21], 2011 | 5 | 11/Female | Sinusitis | Headache, fever, vomiting, change of personality, paresis of the left foot and classical signs of infection of the right upper palpebra | Streptococci intermedius | Burr hole drainage |

A 63-year-old Chinese man presented with cognitive impairment, paralysis, and epilepsy for 1 h.

His symptoms started at 1 h before presentation, which included acute cognitive impairment, right limb paralysis, and recurrent generalized epilepsy.

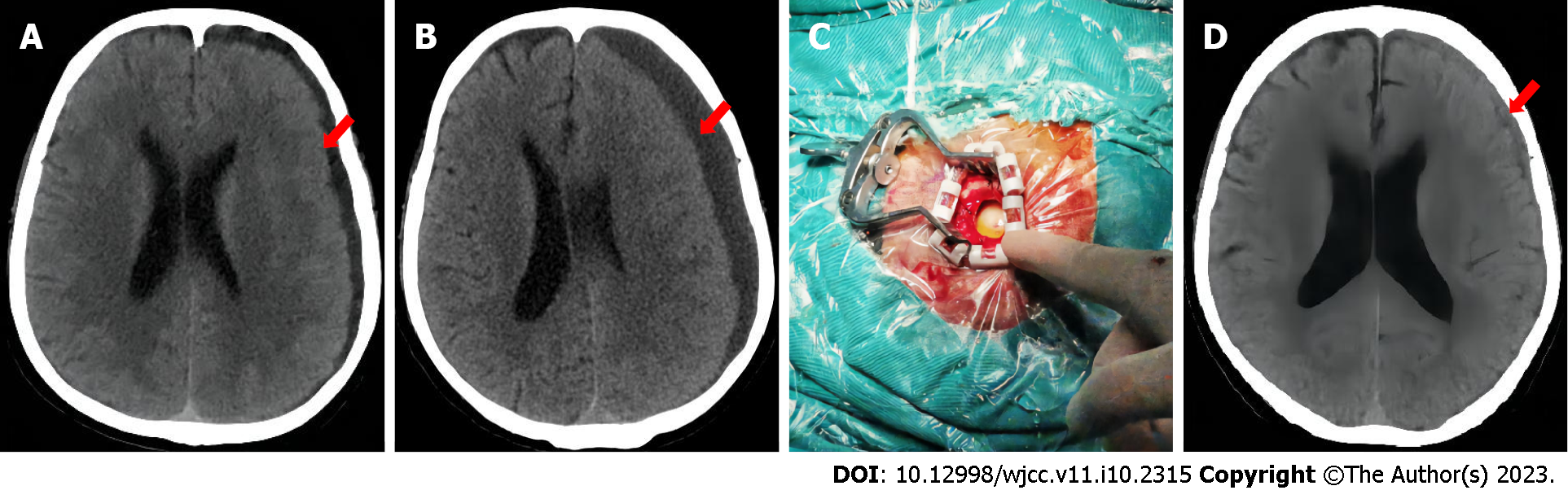

At 1 mo before visiting our hospital, he developed cold symptoms, including a cough and headache, for which he received no treatment. He was brought to our emergency room with a headache, vomiting, and confusion. Physical examination revealed confusion, a Glasgow coma score of 9, and fever (maximum body temperature of 39.5 °C). Lung computed tomography (CT) showed scattered inflammatory lesions in both lungs, while head CT showed a bilateral frontal top subdural effusion that was most obvious on the left side (Figure 1A). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination after SDE showed a white blood cell count of 8157 × 106 cells/L, CSF protein of 3.78 g/L, and glucose < 0.2 mmol/L (blood glucose of 8.91 mmol/L). Three blood cultures and sputum cultures were unremarkable, while two CSF cultures suggested Streptococcus pneumoniae. The patient improved after intravenous anti-infective treatment [vancomycin hydrochloride injection (1 g, q12h) + meropenem injection (2 g, q8h) for 12 d, followed by levofloxacin hydrochloride injection (0.5 g, qd) + ceftriaxone sodium injection (2 g, q12h) for 10 d). CSF examination showed leukocytes of 10´106 cells/L, CSF protein of 0.61 g/L, and glucose of 1.68 mmol/L (blood glucose of 7.47 mmol/L). The patient was discharged from the hospital after 1 wk.

The patient denied any family history of genetic disease or tumors.

On physical examination, his vital signs were body temperature of 36.4 °C, blood pressure of 180/103 mmHg, heart rate of 130 beats per min, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths per min. Acute cognitive impairment, right limb paralysis, and recurrent generalized epilepsy were also observed.

Drainage fluid examination showed a white blood cell count of 3487 × 106 cells/L, CSF protein of 10.27 g/L, CSF glucose of 0.1 mmol/L (blood glucose of 6.88 mmol/L), and culture-positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Head CT revealed that the left frontal top subdural effusion had increased in size, the left lateral ventricle had disappeared, and the midline was shifted to the right (Figure 1B).

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was SDE.

After consultation between neurology, neurosurgery, and the infection departments, emergency burr hole drainage was performed and the dura mater was exposed. The dura mater was yellow-green with high tension (Figure 1C), a pus coating, extremely high pressure, and slow drainage of approximately 60 mL of green liquid. Numerous purulent floccules were seen under the dura, and there was obvious brain tissue edema. The drainage tube provided adequate drainage for 3 d, and his condition improved after antibiotic treatment [vancomycin hydrochloride injection (0.5 g, q8h) for 21 d].

Follow-up CSF testing showed a white blood cell count of 5 × 106 cells/L, CSF protein of 0.35 g/L, and a CSF glucose of 3.3 mmol/L (blood glucose of 9 mmol/L). Head CT showed that the SDE was significantly improved (Figure 1D), the left lateral ventricle was clearly visible, and the midline had returned to the center. The patient’s condition improved and he was discharged home.

SDE is a rare and potentially life-threatening condition if not managed properly. SDE is characterized by collection of purulent fluid between the dura mater and the arachnoid, which can be secondary to meningitis in childhood, especially in infants. Sinusitis, mastoiditis, or otitis media can also cause SDE in older children[5]. Meningitis caused by external infectious factors can cause local inflammation and damage to the blood–brain barrier, which allows bacteria to enter the subdural space between the dura and the arachnoid tissue. Inflammatory products and necrotic tissues can form subdural abscesses.

The most common pathogens in community-acquired bacterial meningitis were reported to be Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae[6]-Streptococcus pneumoniae was detected in the present case. An elevated CSF protein/glucose ratio > 4.65 was also suggested to be an indicator of aggravation of meningitis or transformation into SDE[7]. The protein/glucose ratio in the present case was 18.9, which was significantly higher than the reference estimate. Thus, on the basis of our CSF results, we should have considered the potential for SDE.

SDE is often accompanied by signs and symptoms of infection. However, it can also be asymptomatic in the early stages. Notable symptoms include fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, focal neurological deficits, and altered mental status. Some patients also experience seizures. Physical examination can detect fever, tachycardia, and respiratory failure, while neurological examination can detect meningeal irritation, contralateral hemiplegia, cranial nerve palsy, pupillary disparity, and papilledema. Typically, these symptoms are progressive and may worsen if left untreated. In severe cases, patients can enter a coma or even die[8]. Our patient initially presented with headache, vomiting, and confusion, along with fever and meningeal irritation, which can be easily confused with meningitis. SDE should be suspected if treatment fails or local neurological findings are found during bacterial meningitis treatment.

On CT, SDE appears as a hypodense area at the edge of the hemisphere or at the edge of the falx cerebri. Additional CT scans can improve delineation of the SDE margins. CT can also determine the extent and size of the empyema, and visualize any mass effects associated with displacement of midline structures. Magnetic resonance imaging may have advantages over CT because diffusion-weighted imaging sequences have a high sensitivity for these lesions. SDE can also metastasize into the spinal subdural space, requiring more precise imaging studies[9-11].

Laboratory tests are very important for detecting SDE. Blood analysis can detect leukocytosis, and inflammatory infection can cause a left shift with associated neutropenia. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin are also potential indicators of SDE. However, blood tests are only indirect indicators compared with biochemical CSF tests. Etiological examination is also very important, especially blood culture and empyema stock solution culture, because sensitive antibiotic treatment can markedly improve patient prognosis.

In our case, the first head CT revealed only a small amount of subdural fluid. However, CSF examination suggested a severe intracranial infection. The second head CT showed significant enlargement of the left subdural lesion, disappearance of the left lateral ventricle, and right midline displacement. SDE was diagnosed by combining biochemical examination and the subdural lesion cultures. SDE is easily missed or misdiagnosed, especially when the symptoms are atypical in the early disease stage. With disease evolution, diagnosis can only be confirmed by combining imaging and laboratory examinations[12].

Treatment of a subdural abscess requires multimodal monitoring and multidisciplinary participation, including liaison and consultation with brain surgery, infectious diseases, neurology, rehabilitation, and psychiatry departments[13]. The use of antibiotic treatments alone is rare in SDE. Generally, powerful broad-spectrum antibiotics are used in combination, and the types and doses of antibiotics are then adjusted on the basis of pathogenic microorganism cultures and drug susceptibility tests. Particular attention should be paid to bacterial resistance and the antibiotic treatment time, which generally takes 3–6 wk[14]. Surgical treatment consists of multiple drill holes or craniotomy for drainage and debridement. Craniotomy usually provides better outcomes and fewer recurrences, but requires patient and family consent[15]. Patient outcomes depend on the preoperative status, intervention duration, and treatment aggressiveness. Most patients who are awake and alert have a good prognosis, while coma and comatose patients have a high mortality rate[16]. Although our patient received a sufficient length of antibiotic treatment, SDE gradually developed and aggravated his condition. Fortunately, a craniotomy and drainage was performed in time (the patient’s family did not agree with the craniotomy), and further antibiotics were administered. The patient’s condition improved after the treatment course.

SDE is a neurosurgical emergency. For patients with unexplained subdural effusion, early identification and management are required, especially when asymmetric subdural effusion is accompanied by intracranial infection. Clinicians should consider the potential for chronic SDE, and early surgical treatment may be beneficial.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kung WM, Taiwan; Shen CC, Taiwan S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Thigpen MC, Whitney CG, Messonnier NE, Zell ER, Lynfield R, Hadler JL, Harrison LH, Farley MM, Reingold A, Bennett NM, Craig AS, Schaffner W, Thomas A, Lewis MM, Scallan E, Schuchat A; Emerging Infections Programs Network. Bacterial meningitis in the United States, 1998-2007. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2016-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 715] [Cited by in RCA: 630] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang T, Uddin A, Mobarakai N, Gilad R, Raden M, Motivala S. Secondary encephalocele in an adult leading to subdural empyema. IDCases. 2020;21:e00916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lu HF, Yue CT, Kung WM. Salmonella Group D1 Subdural Empyema Mimicking Subdural Hematoma: A Case Report. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:6357-6363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fernández-de Thomas RJ, De Jesus O. Subdural Empyema. 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Osborn MK, Steinberg JP. Subdural empyema and other suppurative complications of paranasal sinusitis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:62-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van de Beek D, Brouwer MC, Koedel U, Wall EC. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis. Lancet. 2021;398:1171-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yalçinkaya R, Tanir G, Kaman A, Öz FN, Aydin Teke T, Yaşar Durmuş S, Ekşioğlu AS, Aycan AE, Ceyhan M. Pediatric subdural empyema as a complication of meningitis: could CSF protein/CSF glucose ratio be used to screen for subdural empyema? Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:415-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Widdrington JD, Bond H, Schwab U, Price DA, Schmid ML, McCarron B, Chadwick DR, Narayanan M, Williams J, Ong E. Pyogenic brain abscess and subdural empyema: presentation, management, and factors predicting outcome. Infection. 2018;46:785-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Viola S, Montoya G, Arnold J. Streptococcus pyogenes subdural empyema not detected by computed tomography. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e15-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smibert OC, Vujovic O, Hoy J. Neisseria meningitidis subdural empyema causing acute cauda equina syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mortazavi MM, Quadri SA, Suriya SS, Fard SA, Hadidchi S, Adl FH, Armstrong I, Goldman R, Tubbs RS. Rare Concurrent Retroclival and Pan-Spinal Subdural Empyema: Review of Literature with an Uncommon Illustrative Case. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:326-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Adriani KS, van de Beek D, Troost D, Brouwer MC. The diagnostic pitfall of infratentorial subdural empyema. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1076-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Guan J, Spivak ES, Wilkerson C, Park MS. Subdural Empyema in the Setting of Multimodal Intracranial Monitoring. World Neurosurg. 2017;97:749.e1-749.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8908] [Cited by in RCA: 7035] [Article Influence: 2345.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jim KK, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Subdural empyema in bacterial meningitis. Neurology. 2012;79:2133-2139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Konar S, Gohil D, Shukla D, Sadashiva N, Uppar A, Bhat DI, Srinivas D, Arimappamagan A, Devi BI. Predictors of outcome of subdural empyema in children. Neurosurg Focus. 2019;47:E17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hicdonmez T, Cakir B, Hamamcioglu MK, Kilincer C, Cobanoglu S. Giant subdural empyema in a child: a case report. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:632-3; discussion 633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hoshina T, Kusuhara K, Saito M, Mizoguchi M, Morioka T, Mizuno Y, Aoki T, Hara T. Infected subdural hematoma in an infant. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008;61:412-414. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Jorgensen M, Bate J, Gatscher S, Chisholm JC. Invasive pneumococcal disease following treatment for choroid plexus carcinoma. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:647-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kagami H, Muto J, Nakatukasa M, Inamasu J. Infected acute subdural hematoma associated with invasive pneumococcal disease. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2011;51:368-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Greve T, Clemmensen D, Ridderberg W, Pedersen LN, Møller JK. Polymicrobial subdural empyema: involvement of Streptococcus pneumoniae revealed by lytA PCR and antigen detection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |