Published online Apr 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2181

Peer-review started: December 27, 2022

First decision: January 22, 2023

Revised: January 28, 2023

Accepted: March 14, 2023

Article in press: March 14, 2023

Published online: April 6, 2023

Processing time: 92 Days and 20.6 Hours

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy (EUS-FNB) is an excellent investigation to diagnose pancreatic lesions and has shown high accuracy for its use in pathologic diagnosis. Recently, macroscopic on-site evaluation (MOSE) performed by an endoscopist was introduced as an alternative to rapid on-site cytologic evaluation to increase the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNB. The MOSE of the biopsy can estimate the adequacy of the sample directly by the macroscopic evaluation of the core tissue obtained from EUS-FNB. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis is extremely rare and difficult to diagnose because of its non-specific signs and symptoms. Therefore, this challenging diagnosis is based on endoscopy, imaging, and the bacteriological and histological examination of tissue biopsies. This uncommon presentation of tuberculosis can be revealed as pancreatic mass mimicking cancer. EUS-FNB can be very useful in providing a valuable histopathological diagnosis. A calcified lesion with a cheesy core in MOSE must be suggestive of tuberculosis, leading to the request of the GeneXpert, which can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis deoxyribonucleic acid and resistance to rifampicin. A decent diagnostic strategy is crucial to prevent unnecessary surgical resection and to supply conservative management with antitubercular therapy.

Core Tip: In this article, we discussed the role of endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle biopsy as a diagnostic tool in patients with suspicious pancreatic tuberculosis. This review aims to provide knowledge on the utility of fine-needle biopsy and macroscopic on-site evaluation of the core to suspect pancreatic tuberculosis, in addition to diverting the attention of the endoscopists to consider tuberculosis when the core is cheesy.

- Citation: Delsa H, Bellahammou K, Okasha HH, Ghalim F. Cheesy material on macroscopic on-site evaluation after endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy: Don't miss the tuberculosis. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(10): 2181-2188

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i10/2181.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2181

Tuberculosis (TB) is a transmissible disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT). TB was the first cause of death worldwide from infectious diseases until the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic[1]. In 2020, approximately 10 million people developed TB, and almost 25% of the world's population has been infected with MT[1].

The most common site of TB is the lungs; however, in approximately 12.5% of cases, it can affect other sites (extrapulmonary TB), with abdominal localization in 11%-16%[2]. The diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB can be very challenging because the usual method based on the detection of MT is insufficiently sensitive, and other tools based on immune responses cannot always differentiate a latent infection from an active disease[3].

Pancreatic TB remains a rare site of abdominal TB, often misdiagnosed as pancreatic carcinoma. Nevertheless, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with pancreatic fine needle aspiration or biopsy (FNA/FNB) and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are important tools to make the definitive diagnosis and to initiate adequate treatment[4,5].

Recently, macroscopic on-site evaluation (MOSE) performed by an endoscopist was introduced as an alternative to rapid on-site cytologic evaluation (ROSE) to increase the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNB. The MOSE of the biopsy can estimate the adequacy of the sample directly by the macroscopic evaluation of the core tissue obtained from EUS-FNB[6]. In our practice, a cheesy core was found in all patients with isolated pancreatic TB, which led us to perform GeneXpert, which can detect MT DNA and resistance to rifampicin. This diagnostic strategy is critical for avoiding unnecessary surgical resection and for providing conservative management with antitubercular therapy.

In the present article, we reviewed pancreatic TB, discussed the role of EUS with FNA/FNB in diagnosis, and reported the correlation between cheesy core and tuberculosis. Based on this, we also discussed the usefulness of MOSE in avoiding misdiagnosing this rare disease.

Isolated pancreatic TB is an extremely rare disease, even in countries where tuberculosis is widespread. However, due to the development of new techniques like EUS, diagnosing pancreatic TB is becoming easier. EUS-FNB allows obtaining pancreatic specimens with cytopathology. Many cases have been published worldwide in the last few years with different and non-specific clinical manifestations (Table 1)[5,7-10].

| Ref. | No. of patients | Age | Sex | Clinical presentation | EUS finding | Microbiological and histological findings |

| Diaconu et al[5], 2022 | 1 | 55 | F | Fever, jaundice, and asthenia | Cephalic pancreatic lesion with changes suggestive of chronic pancreatitis | Positive culture |

| Miyamoto et al[7], 2022 | 1 | 19 | F | Abdominal pain and weight loss | Positive PCR for MT, granulomas with caseous necrosis and acid-fast bacilli | |

| Hoilat et al[8], 2020 | 1 | 26 | M | Abdominal pain, increased nausea and vomiting | Hypoechoic lesion | FNA: Abundant fibrinopurulent exudate and necrotizing suppurative granulomatous inflammation |

| Ray et al[9], 2021 | 16 | 13-59 | 12 M, 4 F | Epigastric pain, weight loss, anorexia, fever, and jaundice | 5 EUS-FNA; 5 CT-FNA; 6 Surgery | |

| Chang-Xin et al[10], 2022 | 1 | 24 | F | Jaundice | Granulomatous inflammation infiltrated by multinucleated giant cells in FNA; Positive tuberculin skin test and tuberculous infection of T cells spot test |

The systematic review conducted by Panic, including 116 studies reporting data on 166 patients, revealed multiple symptoms dominated by abdominal pain in 74.8% of patients, followed by weight loss and fever in almost half of patients (51.6% and 46.5%, respectively). However, jaundice was found in 20.0% of cases. The most common presentations of pancreatic TB were pancreatic mass mimicking cancer (79.5%), pancreatic head (59.0%), body (18.2%), tail (13.4%), and neck (1.8%). Nonetheless, other pancreatic lesions were reported, like abscesses in 12.1% of patients and chronic or acute pancreatitis in 6.6% and 6.0%, respectively. As an extra-pancreatic localization of TB, peripancreatic lymph nodes were observed in 47.3% of cases. The other sites were rarely described: the spleen (8.3%), intestines (8.2%), liver (6.9%), and lungs (6.3%)[2].

In a study conducted by Ray, 16 pancreatic TB were identified, and the main symptoms were epigastric pain (81%), weight loss (75%), and anorexia (69%). Half of the patients had a fever, and 31% had jaundice[9].

As in pulmonary tuberculosis, immunocompromised individuals are the most affected, particularly in cases of advanced-stage malignant diseases and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), with a high rate of a pancreatic abscess (70%) and mortality (10.8%). In cases of delayed diagnosis and without proper treatment, pancreatic TB can be deadly, and the prognosis is grave due to the underlying disease[11,12].

EUS is considered the main tool for evaluating pancreatic masses and a valuable diagnostic modality for pancreatic TB. It can precisely determine the characteristics of pancreatic lesions (size, vascular invasion, and calcifications) and the aspect of peripancreatic lymph nodes. Combined with EUS-FNB, it has become an excellent investigation to diagnose pancreatic lesions and has established a high accuracy for its use in pathologic diagnosing[13,14].

However, few studies have been published about EUS in pancreatic TB compared to other sites of TB[14]. In the EUS, it can appear as a solid mass or mixed solid cystic lesions, usually with hypoechoic or anechoic echotexture without vascular invasion[14]. Although vascular invasion has been reported in some cases of pancreatic TB, it cannot be used to confirm malignancy[9].

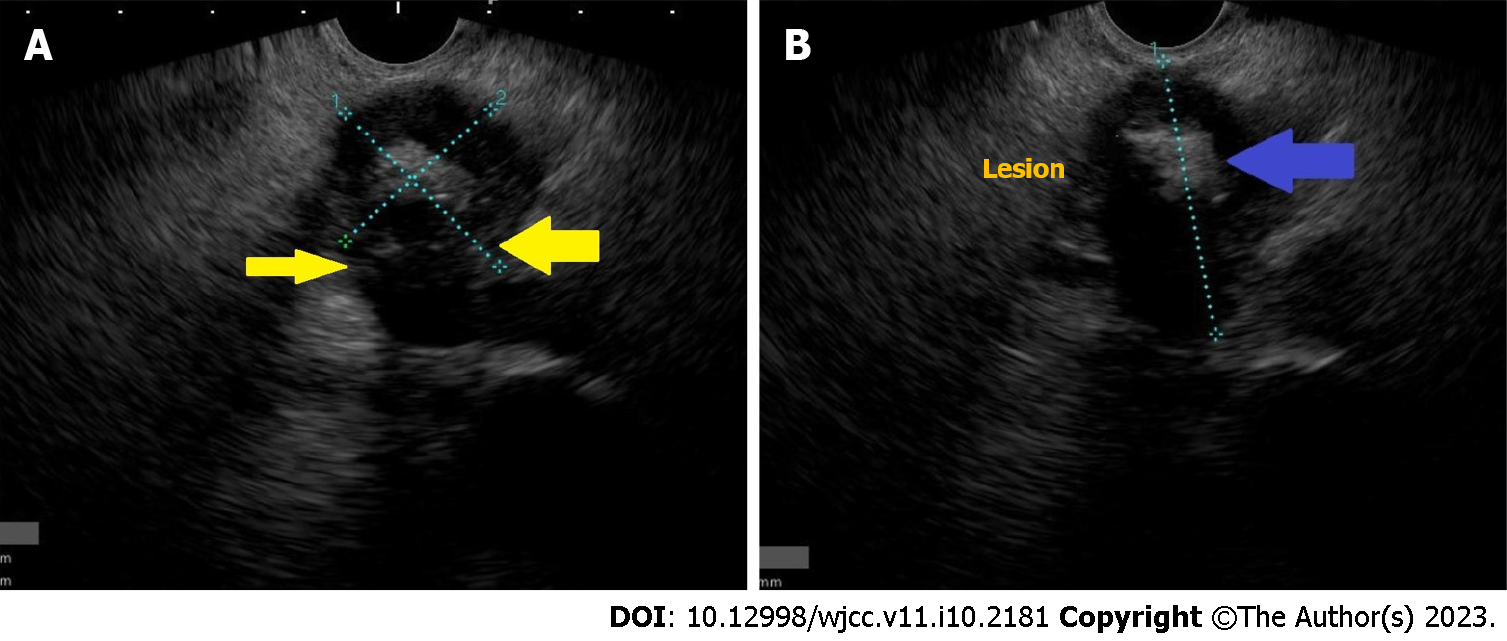

In addition, EUS can demonstrate pancreatic calcifications, reported in 56% of patients, and also detect extra-pancreatic localizations like abdominal or mediastinal lymphadenopathy[15,16]. In our cases, we observed pancreatic mass with central calcification, respecting all vessels (Figure 1).

In the brief communication of Rana et al[17] comparing 25 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma to 6 patients with pancreatic tuberculosis, the EUS appearances were similar between the two groups. However, in patients with pancreatic TB, EUS typically revealed hypoechoic lesions. However, the group with adenocarcinoma had some specific aspects compared to patients with TB: advanced age, high bilirubin levels, significant dilatation of the common bile duct, and sometimes a dilated pancreatic duct.

EUS elastography can help to characterize the pancreatic mass better and differentiate pancreatic TB from adenocarcinoma through the demarcated lesion characteristics. In TB, it showed stiffer tissue than the healthy pancreatic parenchyma. Nevertheless, pancreatic TB and autoimmune pancreatitis have a similar appearance in elastography. Therefore, EUS elastography has a limited contribution to diagnosing pancreatic TB[18].

In addition, EUS allows tissue acquisition by FNB or aspiration by FNA to exclude another diagnosis like adenocarcinoma or autoimmune pancreatitis. At the same time, the endoscopist can perform multiple biopsies of the abdominal or mediastinal lymphadenopathy and the suspicious pancreatic masses, even the smaller ones (less than 1 cm) located in the body and tail regions[19]. With these samples, histopathology can be performed; however, pancreatic fluid culture microbiology (Ziehl–Neelsen staining and acid-fast bacilli culture) and PCR assay (to detect mycobacterial DNA) are required to improve the diagnostic yield (up to 76% for TB vs 95% for cancer)[20]. The EUS-FNA has a good sensitivity (from 85% to 90%) and excellent specificity up to 100%[21].

In the past century, surgical procedures were the main tool to obtain tissue or liquid specimens from pancreatic masses. The development of the EUS with FNA/FNB as a less invasive method has become the procedure of choice for confirming the diagnosis of pancreatic TB[2].

First, after performing EUS-FNA/FNB, every endoscopist must observe the samples. This MOSE will assess the adequacy of histologic cores obtained during EUS-FNA/FNB. This evaluation of the quality and quantity of the core by the operator may help potentially decide the number of passes[22].

Iwashita introduced this concept of MOSE in 2015 when he published his cohort of patients that underwent EUS-FNA with a 19G needle. In this pilot study, the authors observed better diagnostic yield when the macroscopically visible core on MOSE was superior to 4 mm[23].

Nowadays, some authors have proposed performing MOSE of the core as an alternative to ROSE, which requires a cytopathologist's presence[22]. Gaia proposed a classification in his study published in 2022, which included 76 patients performing EUS-FNB for pancreatic and extra-pancreatic solid masses (Table 2)[24].

| Score | Aspects of the core | Classification of the biopsy |

| 0 | No material | Negative |

| 1 | Haematic or necrotic material | Acceptable |

| 2 | ≥ 1 core tissue with ≤ 2 mm yellowish-white | Positive |

| 3 | ≥ 1 core tissue with > 2 mm yellowish-white | Positive |

However, no studies described the sample's aspect based on the final diagnosis. Diaconu reported a case of pancreatic TB with a cephalic pancreatic lesion and changes suggesting chronic pancreatitis; the EUS-FNB revealed purulent material with a positive culture for TB[5]. Therefore, when the EUS-FNA/FNB shows purulent material, a cytological and bacteriological examination must be performed to exclude pancreatic TB.

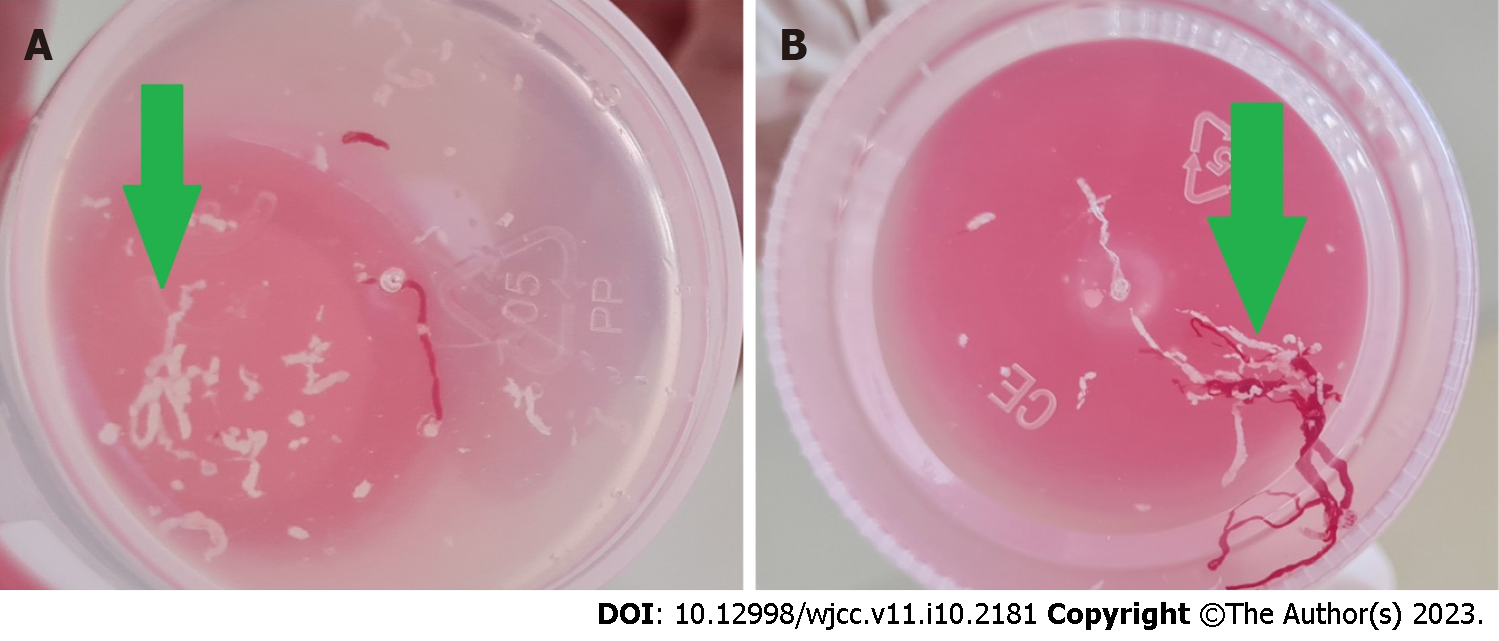

Caseous material was described in tuberculosis as a unique type of tissue aspirate. The gross appearance can be soft, white, or cheesy-looking (caseating) material[25]. In many studies, cheesy material was noted as an aspect of tuberculosis at different sites (Table 3)[26-30].

| Ref. | No. of patients | Presentation | Site of tuberculosis | Procedure |

| Yeat et al[26] | 1 | Pontomedullary junction, ring-enhancing lobulated lesion | Brainstem | Suboccipital craniotomy |

| Gopakumar et al[27] | 1 | Retropharyngeal cold abscess | Cervical lymphadenitis | Surgical exploration of the parapharyngeal space by needle aspiration |

| Ng et al[28] | 1 | Right adnexal mass | Abdominopelvic | Exploratory laparotomy |

| Lakhey et al[29] | 122 | Lymphadenopathy | Fine-needle aspiration cytology | |

| Sahoo et al[30] | 1 | Pain in the left foot | Talus bone | Debridement and curettage of the lesion |

This cheesy-looking appearance was initially reported intraoperatively. However, in the study of Lakhey, which included 122 patients with tubercular lymphadenitis, the acid-fast bacilli (AFB) positivity rate of fine needle aspiration cytology was higher when cheesy material was aspirated (82.3%)[29].

In our series, a young patient was presented with a pancreatic mass with central calcification. Respecting all vessels, EUS-FNB was performed with 3 passes. The core of the first two passes was cheesy, and the third one was also cheesy but a little bloody (Figure 2). This cheesy appearance leads us to perform GeneXpert, which can detect MT DNA and resistance to rifampicin. Positive GeneXpert results and benign-looking histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of pancreatic TB.

A definitive diagnosis of pancreatic TB is commonly based on the microbiological and histopathological examination of a core obtained directly from the pancreas or the peripancreatic lymphadenopathy.

The most common histopathological finding of pancreatic TB on specimens is necrotizing granuloma, reported in more than 50% of cases[15,31]. It is not specific to pancreatic TB as it occurs in other diseases such as Crohn's, sarcoidosis, and autoimmune pancreatitis. Contrary to caseous necrosis, multinucleated giant cells and the identification of AFB are more specific[12].

The diagnosis of pancreatic TB is challenging, and histopathology is not always specific. To have a definitive diagnosis, scientists promoted the development of more sensitive and quick tests such as interferon-gamma release assays, Xpert Ultra, and Xpert MTB/RIF[32].

Worldwide, the most commonly used molecular test for the diagnosis of TB is Xpert MTB/RIF, approved by the World Health Organization in 2013. When performed directly in specimens, it can detect the DNA of the MT complex in biopsies and the rifampicin (RIF) resistance conferred by the rpoB gene mutation detected by nested real-time PCR within 2 h. This test is generally available in less than 24 h[3,9]. Thus, over the last decade, these molecular tests have played an essential role in controlling TB[3].

Even if these tools are more commonly performed, their use for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB, especially pancreatic, has not been well studied. In the Panic review, including 166 patients, PCR confirmed the diagnosis in only 9.6% vs 59.6% for histology[2]. However, in recent studies, PCR is increasingly used to detect TB rapidly with a higher positive rate (43%-67%)[4,33].

In cases of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)- positive patients with AIDS, TB is an extremely common opportunistic infection[12]. The success rate of FNA under computed tomography scan or ultrasound guidance in diagnosing pancreatic TB was 50.0% in the Jenney review for non-HIV-infected patients (37 cases). However, this reported success rate was much lower than the 85.7% rate in HIV-infected cases in the systemic review of Meesir, which reflects the operator-dependent nature of the procedure[11,12].

In Morocco, the correct diagnosis of TB is based on histopathology, whereas bacteriology testing is uncommonly used to confirm TB. In a Moroccan cross-sectional study including 262 patients with cervical lymph nodes, Xpert tests confirmed the diagnosis of TB in 47.3%[34].

The study of Mechal, including 714 patients with pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB, analyzed all the samples using GeneXpert MTB/RIF. Its sensitivity and specificity were almost the same in both groups: 79.3% and 90.3% for pulmonary TB vs 78.2% and 90.4% for extrapulmonary TB, respectively[35]. Therefore, GeneXpert MTB/RIF can be considered the test of choice for diagnosing extrapulmonary TB because of its high sensitivity and specificity[35].

Treatment of pancreatic TB, as the other localization, is based on antitubercular therapy (ATT) using 3 or 4 drugs given for 6–12 mo: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (Table 4 )[15].

| Drugs | Doses (mg/kg/d) | Duration (mo) |

| Rifampin | 10 (8-12) | 6 |

| Isoniazid | 5 (4-6) | 6 |

| Pyrazinamide | 25 (20-30) | 2 |

| Ethambutol | 15 (15-20) | 2 |

According to the initial finding, follow-up is based on clinical improvement, weight, radiology, or endoscopy. Moreover, performing the liver function test is crucial for detecting the hepatotoxicity of ATT. In pancreatic TB, EUS may also be a good modality for follow-up[33]. These tools allow us to decide the duration of ATT, even for pancreatic TB, which is usually 6 or 9 mo, depending on the country. Otherwise, it is suggested to search for other immunosuppression like diabetes and HIV in these patients[15].

In the presence of a pancreatic abscess, percutaneous or EUS-aspiration should be performed to make the correct diagnosis and avoid unnecessary surgery. Some patients, even under ATT, can develop pruritus with cholestatic symptoms or severe cholangitis, and a biliary stent will be placed[10].

Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis is an extremely rare site of abdominal TB, often misdiagnosed as pancreatic carcinoma. Nevertheless, a EUS with pancreatic FNA/FNB is important to confirm the diagnosis. A calcified lesion with a cheesy core in MOSE must be suggestive of tuberculosis and leads to the request of the GeneXpert, which can detect MT deoxyribonucleic acid and resistance to rifampicin. A decent diagnostic strategy is crucial to prevent unnecessary surgical resection and provide conservative management with antitubercular therapy.

To our knowledge, this is the first review relating the correlation between cheesy core and tuberculosis and the importance of MOSE in diagnosing this rare disease, a subject to which the authors wish to draw attention.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Morocco

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chai NL, China; Thandassery RB, United States S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. (accessed on 1 November 2022). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021. |

| 2. | Panic N, Maetzel H, Bulajic M, Radovanovic M, Löhr JM. Pancreatic tuberculosis: A systematic review of symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:396-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huang Y, Ai L, Wang X, Sun Z, Wang F. Review and Updates on the Diagnosis of Tuberculosis. J Clin Med. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Song TJ, Lee SS, Park DH, Lee TY, Lee SO, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Yield of EUS-guided FNA on the diagnosis of pancreatic/peripancreatic tuberculosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:484-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Diaconu CC, Gheorghe G, Hortopan A, Enache V, Ceobanu G, Jinga V, Adrian C, Ionescu VA. Pancreatic Tuberculosis-A Condition That Mimics Pancreatic Cancer. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | So H, Seo DW, Hwang JS, Ko SW, Oh D, Song TJ, Park DH, Lee SK, Kim MH. Macroscopic on-site evaluation after EUS-guided fine needle biopsy may replace rapid on-site evaluation. Endosc Ultrasound. 2021;10:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miyamoto T, Tone K, Inaki S, Saito R, Maeda M, Nagano Y, Akutsu T, Furube A, Gochi M, Motohashi K, Koido S, Takagi M, Kuwano K. Pancreatic tuberculosis in an immunocompetent young female mimicking a malignant tumor: A case report and diagnostic radiological investigation. Clin Imaging. 2022;81:114-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hoilat GJ, Abdu M, Hoilat J, Gitto L, Bhutta AQ. A Rare Case of Pancreatic Tuberculosis Diagnosed via Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration and Polymerase Chain Reaction. Cureus. 2020;12:e8795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ray S, Das K, Ghosh R. Isolated pancreatic and peripancreatic nodal tuberculosis: A single-centre experience. Trop Doct. 2021;51:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wu CX, Xiao LB, Luo ZF, Shi SH. Diagnostic approaches for pancreatic tuberculosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2023;22:107-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jenney AW, Pickles RW, Hellard ME, Spelman DW, Fuller AJ, Spicer WJ. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess in an HIV antibody-negative patient: case report and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Meesiri S. Pancreatic tuberculosis with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a case report and systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:720-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gonzalo-Marin J, Vila JJ, Perez-Miranda M. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6:360-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Maulahela H, Fauzi A, Renaldi K, Srisantoso QP, Jasmine A. Current role of endoscopic ultrasound for gastrointestinal and abdominal tuberculosis. JGH Open. 2022;6:745-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sharma V, Rana SS, Kumar A, Bhasin DK. Pancreatic tuberculosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:310-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gupta D, Patel J, Rathi C, Ingle M, Sawant P. Primary Pancreatic Head Tuberculosis: Great Masquerader of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology Res. 2015;8:193-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rana SS, Bhasin DK, Srinivasan R, Sampath S, Mittal BR, Singh K. Distinctive endoscopic ultrasound features of isolated pancreatic tuberculosis and requirements for biliary stenting. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:323-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dong Y, Jürgensen C, Puri R, D'Onofrio M, Hocke M, Wang WP, Atkinson N, Sharma M, Dietrich CF. Ultrasound imaging features of isolated pancreatic tuberculosis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:119-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sharma V (ed). Tuberculosis of the Gastrointestinal system. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Patel D, Loren D, Kowalski T, Siddiqui AA. Pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking malignancy diagnosed with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Endosc Ultrasound. 2013;2:38-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Varadarajulu S, Wallace MB. Applications of endoscopic ultrasonography in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Control. 2004;11:15-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mangiavillano B, Frazzoni L, Togliani T, Fabbri C, Tarantino I, De Luca L, Staiano T, Binda C, Signoretti M, Eusebi LH, Auriemma F, Lamonaca L, Paduano D, Di Leo M, Carrara S, Fuccio L, Repici A. Macroscopic on-site evaluation (MOSE) of specimens from solid lesions acquired during EUS-FNB: multicenter study and comparison between needle gauges. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E901-E906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Iwashita T, Yasuda I, Mukai T, Doi S, Nakashima M, Uemura S, Mabuchi M, Shimizu M, Hatano Y, Hara A, Moriwaki H. Macroscopic on-site quality evaluation of biopsy specimens to improve the diagnostic accuracy during EUS-guided FNA using a 19-gauge needle for solid lesions: a single-center prospective pilot study (MOSE study). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:177-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gaia S, Rizza S, Bruno M, Ribaldone DG, Maletta F, Sacco M, Pacchioni D, Rizzi F, Saracco GM, Fagoonee S, De Angelis CG. Impact of Macroscopic On-Site Evaluation (MOSE) on Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy (EUS-FNB) of Pancreatic and Extrapancreatic Solid Lesions: A Prospective Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Adigun R, Basit H, Murray J. Cell Liquefactive Necrosis. 2022 Aug 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Yeat CM, Achmad Sankala H, Mohd Zaki F, Mohamed Mukari SA. Tumour-like presentation of brainstem tuberculoma: a lesson learnt. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gopakumar KG, Mohan N, Prasanth VR, Ajayakumar MK. Isolated parapharyngeal cold abscess in a 9-year-old boy. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2019;39:139-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ng BK, Yakob KA, Ng WYL, Lim PS, Abd Rahman R, Abdul Karim AK, Zainuddin AA, Mahdy ZA. Abdominopelvic Tuberculosis Secondary to a Nontuberculous Mycobacterium in an Immunocompetent Patient. Case Rep Med. 2017;2017:9016782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lakhey M, Bhatta CP, Mishra S. Diagnosis of tubercular lymphadenopathy by fine needle aspiration cytology, acid-fast staining and mantoux test. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2009;48:230-233. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Sahoo SS, Tiwari V, Velagada S. A Rare Case of Tuberculosis as a Cause of Lytic Lesion of Talus Without Adjacent Bone Involvement in a Four-Year-Old Child. Cureus. 2021;13:e16909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Vafa H, Arvanitakis M, Matos C, Demetter P, Eisendrath P, Toussaint E, Hittelet AB, Deviere J, Delhaye M. Pancreatic tuberculosis diagnosed by EUS: one disease, many faces. JOP. 2013;14:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Park M, Kon OM. Use of Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert Ultra in extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19:65-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kim JB, Lee SS, Kim SH, Byun JH, Park DH, Lee TY, Lee BU, Jeong SU, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Peripancreatic tuberculous lymphadenopathy masquerading as pancreatic malignancy: a single-center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bennani K, Khattabi A, Akrim M, Mahtar M, Benmansour N, Essakalli Hossyni L, Karkouri M, Cherradi N, El Messaoudi MD, Lahlou O, Cherkaoui I, Khader Y, Maaroufi A, Ottmani SE. Evaluation of the Yield of Histopathology in the Diagnosis of Lymph Node Tuberculosis in Morocco, 2017: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2019;5:e14252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mechal Y, Benaissa E, El Mrimar N, Benlahlou Y, Bssaibis F, Zegmout A, Chadli M, Malik YS, Touil N, Abid A, Maleb A, Elouennass M. Evaluation of GeneXpert MTB/RIF system performances in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |